SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

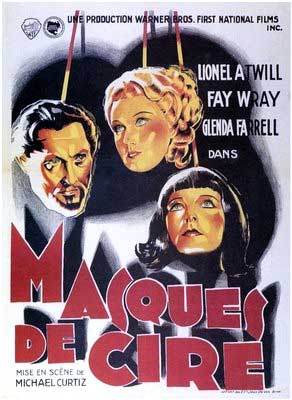

“In London, sculptor Ivan Igor struggles in vain to prevent his partner Worth from burning his wax museum and his ‘children.’ Years later, Igor starts a new museum in New York, but his maimed hands confine him to directing lesser artists. People begin disappearing (including a corpse from the morgue), Igor takes a sinister interest in Charlotte Duncan, fiancée of his assistant Ralph, but arouses the suspicions of Charlotte’s roommate, wisecracking reporter Florence.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

I bring you tidings of comfort and joy, for this week I’m discussing a good film which, like Christmas, only happens once a year. It’s the original version of The Mystery Of The Wax Museum (1933), featuring the fabulous Fay Wray. It was effectively remade in 3-D as House Of Wax (1953) with Vincent Price and…and that’s where they should have stopped, really. The recent House Of Wax (2005) had more in common with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), and it’s only real redeeming feature is the demise of Paris Hilton – really, a spike through the brain shouldn’t have killed her – she obviously wasn’t using it.

Oh, and please do not adjust your set! The Mystery Of The Wax Museum may look odd because it was shot in two-strip Technicolor. The filmmakers knew in advance what it would look like and, incredibly, that it’s exactly what they wanted. I think my old friend George Orwell was right when he said “Three-strip good, two-strip bad.” Half-way between black-and-white and full colour, and a long way from impressive, it was first used in the early twenties on films like The Toll Of The Sea (1922) and The Black Pirate (1926), until Becky Sharp (1935), the first three-strip Technicolor movie. Two-strip Technicolor wasn’t used again until Martin Scorsese shot the early scenes of The Aviator (2004) in that process. No-one had missed it during the interim. Yellow showed-up as orange, blue often turned into green, and it looks as if it’s a faded print, or as if it’s been badly colourised. And there is no such thing as good colourisation, by the way! I am aware this is my own humble subjective opinion, but luckily this is one of those occasions when my subjective opinion coincides with objective truth. That happens rather a lot to me.

Oh, and please do not adjust your set! The Mystery Of The Wax Museum may look odd because it was shot in two-strip Technicolor. The filmmakers knew in advance what it would look like and, incredibly, that it’s exactly what they wanted. I think my old friend George Orwell was right when he said “Three-strip good, two-strip bad.” Half-way between black-and-white and full colour, and a long way from impressive, it was first used in the early twenties on films like The Toll Of The Sea (1922) and The Black Pirate (1926), until Becky Sharp (1935), the first three-strip Technicolor movie. Two-strip Technicolor wasn’t used again until Martin Scorsese shot the early scenes of The Aviator (2004) in that process. No-one had missed it during the interim. Yellow showed-up as orange, blue often turned into green, and it looks as if it’s a faded print, or as if it’s been badly colourised. And there is no such thing as good colourisation, by the way! I am aware this is my own humble subjective opinion, but luckily this is one of those occasions when my subjective opinion coincides with objective truth. That happens rather a lot to me.

Happily, there is much to like about The Mystery Of The Wax Museum, and not just the lovely Fay Wray who, with Joan Crawford, Delores Del Rio, Mary Astor and Janet Gaynor, was one of thirteen up-and-coming actresses chosen in 1926 for sponsorship by WAMPAS – The Western Association of Motion Picture Advertisers. This film is from a major studio, with the budget it required and with many talented people both in front of and behind the camera, as befitted the very first horror film to be set in contemporary USA. I believe you’ll be unusually pleased with The Mystery Of The Wax Museum.

It was directed by the ultra-prolific Michael Curtiz. His career began in Hungary in 1912, where he directed some of that nation’s finest films, before political turmoil prompted his move to Austria. After bringing his tally to sixty, Moon Of Israel (1924) caught the attention of Jack Warner, who invited him to Hollywood. Once there he made another hundred films, of which The Mystery Of The Wax Museum was number twenty-six. Others were Doctor X (1932), Captain Blood (1935), the infamous horse-snuff movie The Charge Of The Light Brigade (1936), Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), and Casablanca (1942), which won him the Best Director Oscar. The one I personally consider his best is The Breaking Point (1950), which is constantly overshadowed by the over-rated Casablanca. Michael Curtiz was a very professional craftsman rather than a gifted cinema artiste, but he gave us many films worth seeing, including this week’s offering.

It was directed by the ultra-prolific Michael Curtiz. His career began in Hungary in 1912, where he directed some of that nation’s finest films, before political turmoil prompted his move to Austria. After bringing his tally to sixty, Moon Of Israel (1924) caught the attention of Jack Warner, who invited him to Hollywood. Once there he made another hundred films, of which The Mystery Of The Wax Museum was number twenty-six. Others were Doctor X (1932), Captain Blood (1935), the infamous horse-snuff movie The Charge Of The Light Brigade (1936), Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942), and Casablanca (1942), which won him the Best Director Oscar. The one I personally consider his best is The Breaking Point (1950), which is constantly overshadowed by the over-rated Casablanca. Michael Curtiz was a very professional craftsman rather than a gifted cinema artiste, but he gave us many films worth seeing, including this week’s offering.

Mad artist Ivan Igor is portrayed by Lionel Atwill, a name well-known to admirers of horror films of the thirties and forties. Born in Britain in 1885, he was appearing on Broadway by 1916 and in films two years later. He was, like myself, a survivor of the great Fox-Trot epidemic of 1919. In 1932 he had the title role in Doctor X and subsequently appeared in Mark Of The Vampire (1935), Son Of Frankenstein (1939), and House Of Dracula (1945). Prominent non-horror roles included The Devil Is A Woman (1935) opposite Marlene Dietrich, and To Be Or Not To Be (1942). A bout of pneumonia took Lionel from this world in 1946 and won’t give him back.

Mad artist Ivan Igor is portrayed by Lionel Atwill, a name well-known to admirers of horror films of the thirties and forties. Born in Britain in 1885, he was appearing on Broadway by 1916 and in films two years later. He was, like myself, a survivor of the great Fox-Trot epidemic of 1919. In 1932 he had the title role in Doctor X and subsequently appeared in Mark Of The Vampire (1935), Son Of Frankenstein (1939), and House Of Dracula (1945). Prominent non-horror roles included The Devil Is A Woman (1935) opposite Marlene Dietrich, and To Be Or Not To Be (1942). A bout of pneumonia took Lionel from this world in 1946 and won’t give him back.

She doesn’t get top billing, but the leading lady in this film is really Glenda Farrell, not the charming Fay Wray. Glenda Farrell played leads and second leads in the thirties and early forties, and character roles thereafter. Screenwriter Garson Kanin once told me, “She invented and developed that made-tough, uncompromising, knowing, wisecracking, undefeatable blonde.” An accurate description of Florence Dempsey, sassy reporter. The newspaper sequences are clearly influenced by those in The Front Page (1931), and may have influenced it’s first remake, His Girl Friday (1940), where the star reporter is a lady who has strong feelings for her editor. In the late thirties Glenda played sassy reporter Torchy Blane in seven films, but some viewers might remember her as the big nurse who intimidates Jerry Lewis in The Disorderly Orderly (1964).

She doesn’t get top billing, but the leading lady in this film is really Glenda Farrell, not the charming Fay Wray. Glenda Farrell played leads and second leads in the thirties and early forties, and character roles thereafter. Screenwriter Garson Kanin once told me, “She invented and developed that made-tough, uncompromising, knowing, wisecracking, undefeatable blonde.” An accurate description of Florence Dempsey, sassy reporter. The newspaper sequences are clearly influenced by those in The Front Page (1931), and may have influenced it’s first remake, His Girl Friday (1940), where the star reporter is a lady who has strong feelings for her editor. In the late thirties Glenda played sassy reporter Torchy Blane in seven films, but some viewers might remember her as the big nurse who intimidates Jerry Lewis in The Disorderly Orderly (1964).

Sweet Fay Wray made this movie during a break in the filming of King Kong (1933). The special effects on that film took so long to do, the cast were able to make other films while waiting for their next scene. Fay also made The Most Dangerous Game (1932) and Doctor X (1932) during these breaks. Born in Canada in 1907, Fay was appearing in routine westerns by the mid-twenties. She met Erich Von Stroheim and he was sufficiently impressed to cast her – without a screen test – as the leading lady in his film The Wedding March (1928). Whilst it was a box-office disaster, The Wedding March was a superb film which got her noticed. Soon after she was the leading lady in the first version of the frequently filmed Four Feathers (1929). After the mid-thirties she was no longer offered the leading roles in major pictures that her talent deserved, just a few minor appearances during the forties and fifties as her stardom slipped away. In 1998 she was guest of honour at a London screening of the restored and re-scored The Wedding March. She passed away in 2004 aged ninety-seven. At least she got the long life she deserved and, courtesy of King Kong, she has a permanent place in cinema history. I’ll never forget Fay Wray, that delicate, satin-draped frame…

Sweet Fay Wray made this movie during a break in the filming of King Kong (1933). The special effects on that film took so long to do, the cast were able to make other films while waiting for their next scene. Fay also made The Most Dangerous Game (1932) and Doctor X (1932) during these breaks. Born in Canada in 1907, Fay was appearing in routine westerns by the mid-twenties. She met Erich Von Stroheim and he was sufficiently impressed to cast her – without a screen test – as the leading lady in his film The Wedding March (1928). Whilst it was a box-office disaster, The Wedding March was a superb film which got her noticed. Soon after she was the leading lady in the first version of the frequently filmed Four Feathers (1929). After the mid-thirties she was no longer offered the leading roles in major pictures that her talent deserved, just a few minor appearances during the forties and fifties as her stardom slipped away. In 1998 she was guest of honour at a London screening of the restored and re-scored The Wedding March. She passed away in 2004 aged ninety-seven. At least she got the long life she deserved and, courtesy of King Kong, she has a permanent place in cinema history. I’ll never forget Fay Wray, that delicate, satin-draped frame…

Ahem. Regular readers who recall my review of The Bat (1959) may recognise Gavin Gordon, who played the murderous police detective in that film. In The Mystery Of The Wax Museum he is Harold Winton, millionaire playboy and temporary suspect. Gavin was raised as a Kentucky hillbilly who didn’t see a film until he was nineteen years old. His big break came in 1930 when he played the sexually repressed leading clergyman in the Greta Garbo film Romance (1930) which, not being that great, propelled him to overnight vague familiarity.

Ahem. Regular readers who recall my review of The Bat (1959) may recognise Gavin Gordon, who played the murderous police detective in that film. In The Mystery Of The Wax Museum he is Harold Winton, millionaire playboy and temporary suspect. Gavin was raised as a Kentucky hillbilly who didn’t see a film until he was nineteen years old. His big break came in 1930 when he played the sexually repressed leading clergyman in the Greta Garbo film Romance (1930) which, not being that great, propelled him to overnight vague familiarity.

This film’s striking sets are the work of master designer Anton Grot. Loyal and sober viewers will remember his creations in Svengali (1931), for which he designed the type of sets that prompt the questions “What was he smoking?” and “Hasn’t he heard of a set square?” His sets in this film don’t quite reach that extraordinarily high standard, but if you were impressed by the morgue set, just wait until you see the laboratory set.

In an inevitably ironic twist, into the cauldron of boiling wax goes the evil Ivan Igor. ‘Moist with his own petard’, you might say – if you were desperate for laughs at this point. We’re not given details of the process whereby Igor transforms his victims into wax statues, but surely just pouring hot wax all over them isn’t enough? If any flesh or organs remain, wouldn’t the powerful aroma of decay make its way through the wax casing? But hats-off to Mister Igor for the design and construction of his own wax mask, a remarkable achievement! I’d love to know how it works. It’s completely realistic and all the known facial expressions are achievable. If only he’d thought of the market potential of this wondrous product, he wouldn’t have come to such an unpleasant end. Of course, his awesome talent for mask-making in no way excuses his deceiving his customers when he tells them Jean-Paul Marat and Charlotte Corday were lovers. An outrageous falsehood if I ever heard one! Marat and Corday met once and once only, on which occasion she assassinated him.

In an inevitably ironic twist, into the cauldron of boiling wax goes the evil Ivan Igor. ‘Moist with his own petard’, you might say – if you were desperate for laughs at this point. We’re not given details of the process whereby Igor transforms his victims into wax statues, but surely just pouring hot wax all over them isn’t enough? If any flesh or organs remain, wouldn’t the powerful aroma of decay make its way through the wax casing? But hats-off to Mister Igor for the design and construction of his own wax mask, a remarkable achievement! I’d love to know how it works. It’s completely realistic and all the known facial expressions are achievable. If only he’d thought of the market potential of this wondrous product, he wouldn’t have come to such an unpleasant end. Of course, his awesome talent for mask-making in no way excuses his deceiving his customers when he tells them Jean-Paul Marat and Charlotte Corday were lovers. An outrageous falsehood if I ever heard one! Marat and Corday met once and once only, on which occasion she assassinated him.

Florence Dempsey is to marry her editor, but I’m not sure I’d call that a happy ending. He’s not exactly a sensitive new-age guy. Throughout the film he has been borish and patronising towards her, which can’t be conducive to a lasting relationship. Perhaps it’s her punishment for neglecting to tell anyone when she discovers the secret passage to the laboratory? At least the ethereal Fay Wray gets a happy ending – and some heavenly close-ups. In some ways, the thirties really were the good old days. Notice how the New York police officer merely strikes the unarmed, defenseless hophead they have in custody? Today’s New York police would shoot him fifty-five times, claim self-defence and be acquitted by the always-conservative judge. Anyway, I hope you enjoyed solving The Mystery Of The Wax Museum as much as I have. If you haven’t, I’ll tell the New York police that you have under-appreciated classic cinema. Now, that really makes them mad! It is, after all, one of the finest treasures of the Public Domain. Please join me next week when I shall discuss another for Horror News. Until then, good night and remember, as my old friend Bela Lugosi would say, “Bevare! Bevare of the big, green dragon that sits on your doorstep – and the gifts it leaves on your lawn.” Toodles!

Florence Dempsey is to marry her editor, but I’m not sure I’d call that a happy ending. He’s not exactly a sensitive new-age guy. Throughout the film he has been borish and patronising towards her, which can’t be conducive to a lasting relationship. Perhaps it’s her punishment for neglecting to tell anyone when she discovers the secret passage to the laboratory? At least the ethereal Fay Wray gets a happy ending – and some heavenly close-ups. In some ways, the thirties really were the good old days. Notice how the New York police officer merely strikes the unarmed, defenseless hophead they have in custody? Today’s New York police would shoot him fifty-five times, claim self-defence and be acquitted by the always-conservative judge. Anyway, I hope you enjoyed solving The Mystery Of The Wax Museum as much as I have. If you haven’t, I’ll tell the New York police that you have under-appreciated classic cinema. Now, that really makes them mad! It is, after all, one of the finest treasures of the Public Domain. Please join me next week when I shall discuss another for Horror News. Until then, good night and remember, as my old friend Bela Lugosi would say, “Bevare! Bevare of the big, green dragon that sits on your doorstep – and the gifts it leaves on your lawn.” Toodles!

The Mystery Of The Wax Museum (1933)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

The name of Glenda Farrell’s character is NOT Florence Dempsey! Her name id simply Florence; her last name is never mentioned in the film. The falsehood that her last name is Dempsey comes from humor-impaired dolts who don’t know a joke when they hear one. In an early scene, Florence walks into a police station and slaps a cop on the back as hard as she can. The cop laughs and says, “Hey, Miss Dempsey, how are they ever gonna decide the heavyweight title without you?” In other words, it’s a reference to heavyweight champion boxer Gene Dempsey.