SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Is it a nightmare or an actual view of a post-apocalyptic world? Set in an industrial town in which giant machines are constantly working, spewing smoke, and making noise that is inescapable, Henry Spencer lives in a building that, like all the others, appears to be abandoned. The lights flicker on and off, he has bowls of water in his dresser drawers, and for his only diversion he watches and listens to the Lady in the Radiator sing about finding happiness in heaven. Henry has a girlfriend, Mary X, who has frequent spastic fits. Mary gives birth to Henry’s child, a frightening looking mutant, which leads to the injection of all sorts of sexual imagery into the depressive and chaotic mix.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Many of the advances in horror cinema come from lowly independent filmmakers who are less constrained by stereotypical conventions and questions of good taste, because their films can make a profit without reaching the family market – they can be as subversive or iconoclastic as they want to be. The tradition of surrealism has stayed very much alive at the low-budget end of the market also. Indeed, the short cuts necessary in cheap film encourage the startling juxtapositions of surrealism. Film stock was never cheap, and the smooth continuities of commercial cinema require high shooting ratios to achieve. Then again, low budget films are often the work of auteurs, people who can pretty much do what they like without a committee of financiers looking gloomily over their shoulders. Such filmmakers are often young, hungry and ambitious, and their films may reflect the slightly desperate vigour such a state induces.

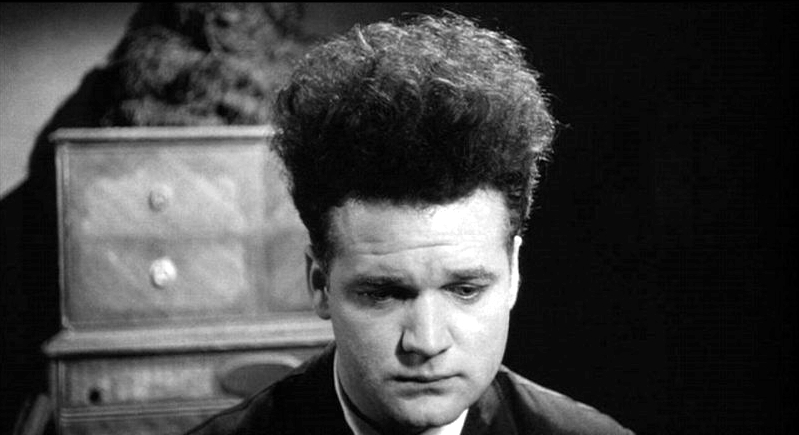

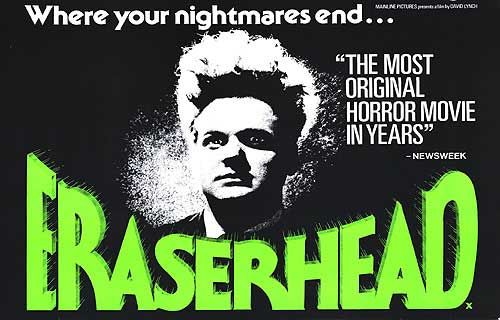

The most extraordinary of these cheap surrealist fantasies is David Lynch‘s Eraserhead (1977). It tells the story of Henry, played with a wild-haired staring autistic quality by Jack Nance. He is inadequate, bluntly polite, withdrawn, almost entirely incapable of ordinary social contact. He lives in a squalid one-room apartment, and has a marginal relationship with a skinny hysterical girl named Mary (Charlotte Stewart) whose family – human rejects living in an urban wasteland – alternate between total passivity and violent mania that borders on epilepsy.

Henry is told he has fathered a child with Mary (“They’re not even sure if it is a baby…”) and she moves in with him. The baby is a mewling mutant horror, unnervingly convincing, which looks like a skinned rabbit with its body tightly wrapped in bandages and swaddling. Mary cannot tolerate the baby and leaves. Industrial noises permeate the film, and the central images are of slime and ooze and small wriggling things. Henry drifts through this nightmare trying to care for the child, and fantasises of a pallid chubby-cheeked girl who sings and dances behind the radiator, squashing foetus-like worms as she does so.

Henry sleeps with the nymphomaniac across the hall, and the bed becomes a swamp. The baby comes out in horrible spots and Henry nurses it then, ultimately maddened, he begins to cut open the bandages with scissors. The swaddling appears to be part of its body, which bursts open revealing a mess of entrails that begin to foam and fill the room. A miniature apocalypse ensues, and a silent man with a horribly scarred face again pulls the lever that he pulled at the beginning of the film, and everything explodes. The man may represent God.

Partly financed by the American Film Institute and actress Sissy Spacek, Eraserhead is the ultimate student film, the ultimate experimental film, and the last word in personal film-making. Both nauseating and compulsive, the industrial and human desolation that it evokes, and the disgust it shows for the body, for sex and procreation, is not for the squeamish. Yet all this is shown with a kind of objective pity, even a warped beauty. We cannot assume that the disgust shown in the film reflects any hatred of the body on Lynch’s part. One of the many points of this strange film may be political: That bodily disgust is, in part, born from human deprivation. The pessimism is not total though, as Henry is not a person without decency.

Is Lynch speaking against parents in our society who desire the deaths of their abnormal children, or is he speaking up for abortions to prevent child abuse by parents who are unqualified to have children, much less handicapped children? In any case, Lynch is on the side of the child and, by the end of the film, so are we. This unique film has marvelous special effects, stop-motion animation, crisp black-and-white photography and fantastic scenic design. Furthermore, it has startling moments of horror, sex and brilliant black comedy – the scene in which Henry visits Mary and her parents is truly unforgettable. It will undoubtedly confuse everyone a little bit as Lynch deliberately leaves some questions unanswered: “I don’t like to give interpretations. I have my own version of everything and, when I’m working, I answer to myself. I’m against a film that makes one interpretation. Abstractions exist all around us anyway, and they sometimes conjure up a thrilling experience.”

Eraserhead is the kind of early work that would naturally lead to an Elephant Man (1980), a Blue Velvet (1986) or a Mulholland Drive (2001). I was lucky enough to meet Mr. Lynch on the set of Nadja (1994) which, although not directed by him, was produced by Lynch, earning him a cameo appearance as a morgue receptionist. I asked him why so many of his films are populated by such sick and disturbed individuals: “They’re not really sick. I think what happens is, like Rodney Dangerfield says, the only normal people are the ones we don’t know. You meet somebody and they seem normal, and then you get to know them and, just like in films, the negative things stand out more than the positive things. You’re more shocked by discovering something negative in them, and it’s upsetting. What’s really happening is, there’s all sorts of negative things and all sorts of positive things, and a strange kind of war between them.”

Eraserhead is full of nightmarish imagery and existential horror that would be revisited in most of Lynch’s films, who frequently claims to have had a normal happy-go-lucky mid-western childhood, yet his movies are obsessed with the seedy underbelly of ordinary life: “If we didn’t want to upset anyone, we could make films about sewing – and even that could be dangerous. I believe in very strong films and I don’t apologise one bit, as long as there’s a balance. I don’t know why there’s violence in American films, probably because there’s a lot of violence everywhere, in the air. I believe in it, but I don’t want to champion it. Maybe I’d have to spend a long time with a psychiatrist to know why I like it.”

And it’s with that thought in mind I’ll quickly thank the Washington Post and Video Magazine for assisting me in my research for this article, and graciously invite you to please join me again next week when I have the opportunity to raise the hackles on your goose-bumps with more ambient atmosphere so thick you could cut it with a chainsaw, in yet another pants-filling fright-night for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews