“And where the offense is, let the great axe fall.”

–William Shakespeare, Hamlet.

Art takes many forms, including performance. If there is no such thing as bad art, as some profess, is there such a thing as a bad theatrical performance? Yes. And the affirmation comes without subjective discourse. When a performance undermines the audience’s suspension of disbelief, it’s not good.

For a theatrical work to succeed, audiences must lose themselves in a performance. When audiences know an “actor is acting,” dramatic impact weakens considerably. “Hammy” performances aren’t well-received, except when they are.

Forgiving audiences may find an endearing ham actor enjoyable and provide box office receipts telling a sincere tale about how well they receive a performance. Everyone – ham actor and audience alike – enjoys themselves and appreciates the show. It is a night out and good fun.

And then the critics interject to disrupt the collective harmony. At least that was the case at one time, when a select number of the artistically snooty wielded influence.

Decades ago, long before online critique platforms catered to niche audiences, newspaper and highbrow magazine critics sometimes presented pigeonholed opinions about movies, books, and the ancient medium of theatrical performances. What they critiqued mattered naught. Critics, then and now, often want everything to be about them, and their frequently self-serving reviews ruined careers, thanks to classist concepts of taste, a stand-in for smothering elitism. That’s how it was 50 years ago when a minute number of critics held court from a limited number of mainstream publications.

And then arrived Edward Lionheart, the savior of good and bad acting and de facto champion of low-grade Shakespearean plays and B-level horror films.

A Well-Grac’d Actor Leaves the Stage

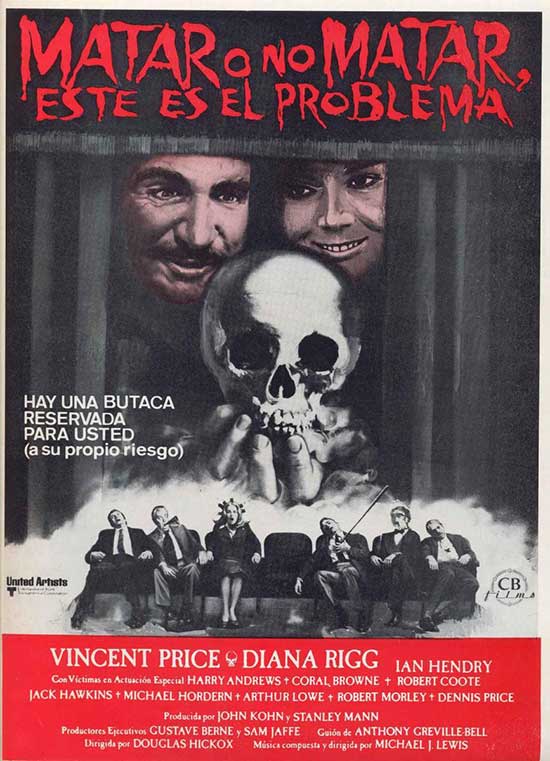

Vincent Price proved “all the world’s a stage” in bringing Edward Lionheart to life in Theatre of Blood (1973), a performance that ranks as a top highlight of a storied career.

The early 1970s brought an unavoidable new direction for the legendary horror star. Although an iconic figure with more than two decades of horror movie hits, Vincent Price changed his career course. The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) and Dr. Phibes Rises Again (1972) proved successful, even though the horror genre found itself careening into a cynical new direction. Vincent Price chose to step away from lead roles in “Vincent Price films” after the release of the deliriously underrated Madhouse (1974).

By 1974, the 64-year-old Price opted for more lucrative and less physically demanding work. Price hardly fell out of demand, as he continued to appear on television series and game shows while lending his notoriety to commercials. Price also provided narration and voiceover duties on TV and radio and made several cameo film appearances, with his most famous being his swan song in Edward Scissorhands (1990).

Madhouse ominously predicted what was to come and likely sent a warning to Price. Madhouse underperformed at the box office, and Vincent Price and Peter Cushing’s names couldn’t make it a hit. Theater and drive-in horror fans wanted edgier, more exploitive fare, while the standards-and-practices ruled television world seemed more amicable to quaint frights. Older and younger horror fans welcomed iconic figures, and Price made the right move and continued working until a year before his passing.

Maybe there was another reason why Price felt comfortable leaving lead roles. The actor appeared in a film he ranked among his favorites, the classic horror-comedy, Theatre of Blood. A critical and commercial success, Theatre of Blood deserves its following and accolades.

Dark humor and garish murders captivate viewers on a visceral level, but it’s the not-entirely-hidden subtext that makes the bizarre masterpiece compelling.

Thou Art False as Hell

Critics are dying in the most peculiar ways, Shakespearean ways. Literally. Their dismissals and scorn drive the depressed Bard-centric actor Edward Lionheart to suicide in front of daughter Edwina. Did Lionheart’s suicide attempt succeed? No, he’s gone mad, and his behavior is not performance art. He’s teamed with an entourage of outcasts to re-enact famous scenes from Shakespeare plays, scenes involving comeuppance and death, and the critics find themselves cast in the fatal roles. They also find Lionheart’s new vengeful performances are more than an act.

While rooting for the underdog antihero gives audiences a way to vent, why would anyone rally behind Lionheart’s psychopathic behavior?

Unlike Dr. Phibes and sequel, Theatre of Blood wallows in moral ambiguity allowing audiences to root for an unhinged murderer. The dark comedy’s structure creates the amoral moving canvas by placing sympathy in a Nietzschean way. Nietzsche warned readers to never trust the artist, for the artist crafts the horizontal and the vertical. What the viewer sees in art comes with a subtle – and sometimes heavy-handed – confidence job.

The artist creates the landscape and all that is inside of it. Every element the artist crafts exists to present a particular theme, theory, or argument across a specific way for a preferred outcome. In Theatre of Blood, the collective artistry of actors Vincent Price and Diana Rigg, director Douglas Hickox, screenwriter Anthony Greville-Bell, and others come together to paint murderer Lionheart as the victim through overindulgence of sympathy.

The critics slaughtered by Lionheart come off poorly, as audiences lack any sympathy for them. The dearth of support seems understandable. The critics’ pendulum-like behaviors swing from obnoxious to elitist to boorish, leading audiences to get behind Lionheart and daughter. Do the critics deserve to die for writing bad notices? No.

The critics gave him bad reviews for his work. And why wouldn’t they? Edward Lionheart’s performances turned Shakespeare tragedies into paradies. Lionheart didn’t win a critic’s award, an award he did not deserve. The ham actor’s ego ending up bruised, a humiliation leading to his supposed suicide and subsequent vengeful rampage. How could anyone rally behind a murder spree rooted in violent, delusional entitlement?

Because Lionheart’s not doing it for himself. He’s out there fighting for all the lives these critics destroyed. He’s punishing them for ruining people’s livelihood and well-being. He’s a stand-in for anyone who understands the wrongful unfair treatment That empathy net casts far and wide.

The Merchant of Resentment

While not supernatural or superpowered, the aged, sociopathic Edward Lionheart is driven. The murderous histrionics come off as so over-the-top that Lionheart’s recreation of Shakespearean death scenes evokes more humor than revulsion. The crazed Lionheart appears to be enjoying himself getting back at his critics, making the outrageous revenge scenes even more absurd. Revenge propels his actions, but what drives his desire for revenge? Resentment.

Resentment reflects an outwardly simplistic emotional response: targeted hatred. The causes behind resentment may come with greater complexities. Edward Lionheart feels enormous resentment towards his critics because he feels wronged.

Edward Lionheart feels wronged not from the poor reviews. Lionheart continued to receive poor reviews because he continued to work. No matter how many terrible notices the actor received, he found himself cast in another lead role. Working actors that successful would probably laugh at bad reviews.

It wasn’t the dreadful reviews or lack of accolades and awards, though, that drove his resentment. The critics did more than savage his performances. They did so on an inexplicably personal level, intended to inflict pain. Why?

The invective emotion cuts in both directions. As critic Peregrine Devlin (Ian Hendry) points out, “You begin to resent an actor if you always have to give him bad notices. Perhaps the critics felt Lionheart wasted their time and found needling and torturing the man served as revenge. Even jealousy could factor into their resentment. Critics live in an insular world, and Lionheart enjoys the reverence of an audience. Underlying burning resentment guides their fingers on the typewriter keys.

What the critics didn’t realize was that their resentment begat resentment and homicidal blowback. Edward Lionheart finally had enough with them, and he had enough of the true source of his resentment. They made him look bad in front of his daughter.

A Fair and Gracious Daughter

Terrible critical reviews may sting, but a daughter’s love might dull the scorn directed at Edward Lionheart. Furthermore, the relationship between Edward and Edwina adds a tremendous level of audience sympathy for the tragic character.

Horror film antagonists tend to be self-centered, and Edward Lionheart remains no exception. What separates Lionheart from legions of one-note villains is a loving relationship with his daughter, albeit a toxic and codependent one.

Edwina maintains a lower profile career in the theater while maintaining a strong, supportive devotion to her father. The support extends to assisting his homicidal activities. With the words, “You have begot me, bred me, loved me: I Return those duties back as are right fit,” Edwina reveals nothing undermines her loving devotion. She happily joins him on a mad killing spree.

Edwina’s as delusional as her father, and the delusion extends to her seeing him as a great actor. Or, does she?

Perhaps Edwina privately acknowledges her father’s artistic limitations, but wishes not to burst his illusions. What purpose would doing so serve? He’s an aging actor, one likely facing retirement. As Edward’s career comes to an end, Edwina shifts to a protective caretaker role, Edward’s role when Edwina was a child.

The good daughter understands the fantasy image her father embraces provides him with solace in life. She joins in his desire to destroy the critics not to punish them for failing to recognize his genius, but for the sin of tormenting a generally good man.

Edwina’s as delusional as her father, and the delusion extends to her seeing him as a great actor. Or does she?

Perhaps Edwina privately acknowledges her father’s artistic limitations but wishes not to burst his illusions. What purpose would doing so serve? He’s an aging actor, one likely facing retirement. As Edward’s career ends, Edwina shifts to a protective caretaker role, Edward’s role when Edwina was a child.

The good daughter understands the fantasy image her father embraces provides him with solace in life. She joins in his desire to destroy the critics, not to punish them for failing to recognize his genius, but for the sin of tormenting a generally good man.

Sentimentality doesn’t excuse serial killings. Things don’t end well for the Lionhearts, as Theatre of Blood ends with the father and daughter meeting the fate the path to revenge usually delivers. With all their Shakespearan experience, you’d think they’d realize they were writing their own tragedy.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews