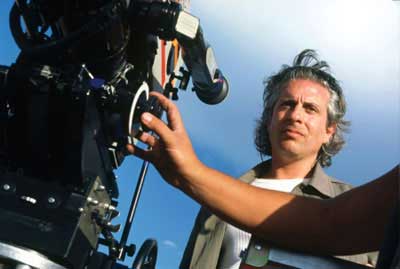

WHO: Elias Merhige – director

WHO: Elias Merhige – director

MOVIE: “Begotten”, “Suspect Zero”, “Shadow of the Vampire”

Interview with Elias Merhige – 01.31.09

(INTERVIEW BY SCOTT ESSMAN)

Elias Merhige, born in 1964, grew up in Brooklyn, and went to school in Tenafly, New Jersey before attending film school at State University of New York at Purchase where he received a bachelor’s degree in 1987. This exclusive interview concerns the making of his controversial non-dialogue feature film, BEGOTTEN. The interview was conducted for DIRECTED BY Magazine at the time of the release of SHADOW OF THE VAMPIRE, Merhige’s first feature. Special DVD copies of BEGOTTEN are now being made available as a not-for-profit item by DIRECTED BY Magazine for a short time only.

What was the earliest genesis of “Begotten”?

With “Begotten”, I was working with a lot of actors and artists at the time, and I had a small theatre company in New York. And we were doing a lot of experimental theatre. And it was the sort of thing where I had envisioned “Begotten”–I mean, a lot of my influences at the time were Antony Narto’s theories on theatre and art. You know, I mean like the theatre and its double; theatre as play: all of these very luminal essays about aesthetics and what theatre needed to be in the 20th century. And one of the things that was really important, I thought, was that I had never really seen any of Barto’s ideas or any of these very powerful ideas on aesthetics that Nietzsche had about plays and early Greek drama, and I hadn’t seen any of it on film. I mean really to its fullest extent. And so it was the kind of thing where at the time–I wrote the script when I was 20.

And I originally thought of it as a dance theatre with live music piece that we would do at Lincoln Center. I was making it up as I was going along. But then I found out what it would cost to get the theatre space, what it would cost…. And it would actually cost me, at the time, a quarter of a million dollars to produce the show. And so I thought, “It’s weird. There’s got to be a better way to do this.” Then the challenge became, really, creating the world. Because “Begotten” really is a world more than anything. It’s a world. And so that got me into shifting my whole focus into making a film.

Now how long of a period, from when you wrote the script to when you said, “Okay. I want to do this as a film.”?

About six months.

And you were in your early 20s at the time?

Yeah. And I finished the film when I was…. It took me three and a half years to make the film. That was not because of money. It was because–I built the optical printer that I did all the special effects on. I did all of the cinematography, all of the special effects, everything. And it was really a very powerful experience. It changed the lives of every single person involved with the film. It was really one of these transformative, ritualistic experiences, where the experience itself became what it was about, and the film was just ancillary to the experience. And–sort of like the experience was the flame–and the work itself, the film, sort of became like the vapor, the light coming off the flame. But that was a very powerful experience. But one of the challenges with that film was that it got me into the whole investigative process of “All right, if you want to create something that you haven’t seen before, how do you do it?”

And so I would just talk to everybody. I would call people up. I would call my new cinematographers and sit down with them for hours and talk to them. I would go to–I went to every laboratory in New York City, sat down with their timers, with their developers, and asked them how they–what is it about developing film, and if you develop it higher than the normal mean or lower than the normal mean in terms of the temperature of the developer bath, what does it do to the film? And they would do these experiments for me, and I would actually look at this stuff. You know, people are really helpful. And then I got ahold of a 16mm Aeroflex camera that was borrowed to me, and I started doing every experiment in the world, sort of developing my own film. I started doing just every conceivable thing from in a darkroom on rewinds running the unshot negative through sandpaper, you know, to scratch the negative before I shot on it.

And I still wasn’t getting the results that I thought I really needed. And then one day, in the conversation, somebody told me about the kind of control that you have with an optical printer. And when it came time to try and make a deal to get an optical printer, it turned out that it would have cost me millions of dollars to have an optical printer for the amount of time that I needed it. And to buy an optical printer would cost me, at the time, since that was what they used to do special effects at the time–there was no CGI — the cost of an optical printer at the time was more than–you know, between a quarter and a half million dollars.

Yeah. Late 80s. Mid- to late 80s. So I built one. And I went around getting parts from different camera places, different special effects houses, and they would each say, “Hey, we’re not using this old…” I mean, I had an old 1936 Mitchell camera, like number 13. It was just this horse. This workhorse. And then I had a friend of mine that was an electronics engineer out at Brown. And I drove him crazy. I don’t think he talked to me for years after helping me with the electronics on it. And then I used an Italian projection gate from the 1940s.

SCOTT: How did you get these parts? Were they paid for, or did you get them–did people loan…?

They were things that no one was using, and they just had it. It was like just part of their inventory. And they said, “No one on earth is ever going to use this. You can have this.” And I would give them like a laundry list of things that I needed, and they would say, “Well, we don’t have exactly that, but we have this.” And then what I would do is say, “Okay, if I modify this, if I machine it in a slightly different way–can I do that?” And they would say, “Yeah. Sure.” When I needed money, I just went to these guys and said, “I’ll do some special effects for you. If you guys ever get overloaded with work, I’ll do it for you for like half of what any of your other cameramen would do it for.” And that was still a lot of money. That’s how I paid for the sound mix for “Begotten”, doing all that stuff.

For various different people? Small little jobs?

Various different people. Yeah. There was like Disney jobs–there were just various different things they farmed out to me. There was this one rotoscope job that was like six seconds of this old man looking up at a spire and there was blue screen in the back, and they wanted mountains in the background. They wanted the sun to go down, the stars to come up and the moon to rise over one of the mountains. So a friend of mine, Michelle, rotoscoped the whole thing. Airbrushed the stars in, animated the whole thing, and it looked fantastic. It was actually cool doing it. I forgot that it was for a movie or anything–it was just like my own little six-second world.

You optically printed it off the film yourself?

Yeah. Everything was done on film. Everything was done very physical. There were no CGI or no computer elements. “Begotten” was shot in 16mm.

So the optical printer could be used for either?

Yup. All you got to do is just take a different camera–you know, I had a 16 camera mount. I used to take that off, put a 35 on. Which in hindsight, I mean, that’s what I should have done. I could have just blown up the film myself instead of…. But that’s something I plan on doing. I do plan on blowing up “Begotten” to 35. Not that it needs to be blown up–I just feel like doing it. Then I did the sound. And the amazing thing, and the parallel between that film and “Shadow of the Vampire” is that there was a very Zen-like incredible experience in directing “Begotten”. Because I am looking through the camera, operating the camera, speaking to the actors; and I’m seeing an idea that’s coming out of my imagination becoming flesh and blood in the characters and friends that I’m working with. Then that’s being reflected back into the camera and recorded onto the film. And it’s like this process where it’s moving out of my brain into flesh and blood and back into the lens onto film. It was just an extraordinary thing to be able to speak, and–well–“Begotten” is a silent, obviously.

Non-dialogue. Was there ever a point in which you thought, “It’s my first film. I’m already directing it. I’ve already written it.” Was it an artistic choice to say, “I should also operate the camera. I should also star in all the stuff myself.” Did you ever feel like you wanted another point of view?

E.M.: No. It felt very natural. There was a great deal of innocence to making “Begotten”. It just felt like–well, I was so curious about all the different things that needed to [be done]…. And it was such a homemade, handmade, handcrafted piece of work that it just made sense that [I crew everything myself]…. Because I’m sort of neurotic anyway, when it comes to doing things. I have to just know that something is done, and when it’s done, that it’s done properly.

Where was “Begotten” photographed?

Where was “Begotten” photographed?

There were three or four different locations, but the main one was a construction site right on the border of New York State and New Jersey, just at the northern part of New Jersey. And they were constructing this corporate park. They were making this huge corporate park. And it–and they just had devastated the landscape. So I had talked to the engineer, the main engineer that was engineering all the groundwork there, and told them what I was doing. And they actually–they thought I was crazy at first, but when I explained to them how I was doing it and what I was doing…. I don’t know. It was the sort of thing where, I guess, they felt sorry for me, you know, and they just decided, “Yeah, you can shoot that movie here.”

And then, on top of it, as time went on, I told them, “You know, the composition is almost perfect.” And I would have them look through the lens, you know? And I’d say, “If it just had a mountain right there, you know? If it just had a mountain of rock just right over there to the right, it would be perfect.” And they would make one for me. They would bring in bulldozers and heavy dump trucks and they would just make a mountain. It was remarkable.

You didn’t have to pay for the location at all?

No.

How long were you there? How many days in the quarry?

Would you believe it was just like 20 days. It was all weekends. My agreement was that I would shoot when they weren’t working. And their agreement was to have all their equipment out so I could shoot. [20 days in the quarry for the last third of the film… earlier in the film was at a lake. The middle section was in a house.] A friend of mine was going to hook me up with some Indian friends of his down in Santa Fe or Albuquerque. And they were going to take me on this like fun ritual thing that they were doing in the mountains. Anyway, I never hooked up with them, for some reason–miscommunications. So I ended up going into the mountains myself anyway, and shooting some of those sunrises.

I spent a couple of days just shooting time-lapse sunrises and sunsets. That’s where you get that big flat expansive [view]. And with that film, you know, that was the idea that I didn’t want you to be able to tell the difference between the moon and the sun. And whether it was day or night. It’s just this idea: we have opposites just colliding and coming together. And then when I finished the film, it took me two years to get it out there.

I mean, I would show it to distributors and people out there, and they would say, “Listen, if you can show this for free in some high school basement in the Bronx, you’re lucky.” And I know people that were really brutal, and I hated them. And I just had this sort of “Well, what do they know?” kind of attitude. And then the film went to the San Francisco International Film Festival. And it was there that Peter Scarlet and Tom Luddy showed the film to Susan Sontag, who then called me up. And I projected the film in her living room for like 21 of her closest friends, and it was remarkable. Because she brought it to the Berlin Film Festival, and said just wonderful things about the film, that…. She used the word “masterpiece”. I hate to use that word, but she really loved the film and thought it was just a profoundly original piece of work. And then Werner Herzog had seen the film at just about the same time. And he, also, was very supportive. He was very supportive of the film.

Did Sontag get the film to Nicolas Cage somehow? How did Nicolas end up seeing it?

Did Sontag get the film to Nicolas Cage somehow? How did Nicolas end up seeing it?

Crispin Glover had given Nick a copy of “Begotten” as either a birthday present or just as a gift. And Nick, just out of his own volition, saw the film and said, “You know, I’m moved by this piece of work.” And then when he opened a production company, Saturn Films, he gave the videotape of “Begotten” to his partner at the time, Jeff Levant. And said, “We need to find this guy, ’cause I’d like to work with him.” And that’s the way it evolved from there. And then we met, and a 45-minute meeting turned into a three-hour meeting, and we realized that we all liked each other very much as people. And three days later, they sent me the script to “Shadow of the Vampire”. And when I first read that script–you know all that stylistic stuff, with going from color to black-and-white and black-and-white to color? That was stuff that I saw from the first reading of the script.

I knew exactly how to do it. And that’s what I loved so much about the script is that it was this great balance between technical innovation and great story-telling. And for me, I knew that I could make something really terrific out of this.

How long did you spend in post on “Begotten”?

E.M.: That was what took all the time.

That was three years?

Yes. It took me eight months to build the optical printer.

That’s with film in the can?

Yes. That just drove me up the wall. ‘Cause if it’s just a hair off, it’s off. That’s all. It doesn’t work. And it just looks stupid. And it’s wrong. Everything has to be very exact.

How long on the sound mix? …the whole movie–about 88 minutes of sound effects.

Got to tell you–that soundtrack–that was something that Evan Album–he’s a guy that a friend of mine at the time, (he was the assistant director on “Begotten”, Tim McCann), had a friend of his who was painting people’s houses–not doing frescoes, just painting the houses. And I met this guy, and I was talking to him and I was just having regular conversation with him ’cause we were both waiting for Tim. And it was, “Well, what do you do besides painting houses?” And “I compose music.” I go “Really?” “Yeah.” I go, “On what? What instrument’s your instrument of choice?” He says, “On the bass guitar.” I said, “Really? You compose music for the bass guitar. I’ve never heard music composed just for the bass guitar.” I said, “I’d like to listen to it.” So he gave me a tape. And there was nothing in this tape, in this recording that sounded remotely like a bass guitar. This guy was functioning on a totally, completely different plane of existence. And it was at that moment that I thought, “This guy is the kind of person….,” ‘Cause when you talk to composers, they’re all like, “Hey! This is the happy–this is my happy stuff.

Oh, this is my scary stuff. Oh!” And with this guy, it was not like that at all. And that soundtrack took a year to do, because–this is going to sound a bit odd, but–we recorded the sound of feet walking on gravel in the winter, feet walking on gravel in the spring, feet walking on gravel in the summer, and feet walking on gravel in the autumn. And used all of them at different points in the film and orchestrated all of that in this careful kind of like mosaic within the film. That’s how obsessively detailed that film was. I spent every frame–I mean, I was looking through the camera every single frame…. Just remember, there’s 24 frames in a second. And 24 frames in a second, it would take me about 10 hours of time to get about a minute’s worth of screen time, of film. When you think about that ratio of labor, it’s very intense.

At first, did you let many people see it?

At first, did you let many people see it?

And in the beginning, when I finished it, I was very protective of it. ‘Cause there were people that hated the film and just didn’t care whether it got out there or didn’t get out there. So I was very protective of it. And there was never a moment that I didn’t totally believe in the film. I always believed in the film. And it’s that sort of thing where, when Susan Sontag saw it, it was a major epiphany and pinnacle in my own consciousness. Because it was like, “Okay. Now somebody who I’ve always revered and respected believes in my work. And believes that it’s great.” And I knew it was great, but when you have it mirrored off of someone who is great, like Susan Sontag, it enables you to suffer all the crap that you have to go through to get a film off the ground, get something out of development hell and into reality.

You were able to get it out there somehow?

The film was distributed on VHS. So people could buy it from Virgin Megastore. It wasn’t just myself that had to give them a copy of the tape. Rocket Video had the film. Jerry’s Video over in Hillhurst that has the film as well. The thing, for me, in making a film, is I that have to just be 300% in love with what it is that I’m doing. I’m not going to spend two or three years of my life on something that I’m half-hearted about, you know?

My take on “Begotten” is pretty clearly that this divine being, in the beginning, is almost sacrificing himself for the birth of the next generation, which becomes Mother Earth…. Actually, in the film, Mother Earth comes from behind him. And…

She’s sort of born from him in a very theatrical way.

Yeah. Born out of him, and he’s dead. And then ejaculates him….

Yeah. Inseminates herself.

And then from that comes….

Comes this new world order.

Who’s, hey, got a tough life. Almost an oppressive kind of way….

Well, it’s interesting, ’cause you have this, like, the patriarchal world, sacrificing itself, giving birth to this matriarchal world, that then gives birth to this new kind of, like, child, who’s a balance between the masculine and the feminine, the earth and the sky, and then is ultimately sort of sacrificed….

But then begets greenery and the earth as we know it. Which was a neat effect. I’m sure you did that on your optical printer.

Yeah. I did a lot of that with time lapse, too. In a terrarium, I had little things growing.

A small terrarium?

No, a large terrarium. And–but it’s the kind of thing where–with “Begotten”, I always felt that, having been a big Nietzsche fan at the time, this idea of circularity of time, the idea of the eternal return, the idea that everything is a circle or a sphere…. And certainly Einstein’s theory of relativity, you know, that if you go in two opposite directions, you’re eventually going to meet again. ‘Cause the world through Einsteinian physics is spherical–the universe is spherical. So, it’s the idea that–imagine that we had a culture, like 4,000 years ago or 10,000 years ago, that had the technology with cinema, to make movies. And that you’re looking into a sort of archaeological discovery of this world, that is now extinct, and was sort of a pre–predecessor to the world that we live in today.

When the earth was really new.

Yeah, exactly.

And I took the band of quote, kind of “lepers” or whoever, just to be sort of the outcast, the marginalized and the decrepit of the earth, who don’t know what they’re doing. Almost–I’m not specifically a religious person–but I almost read it as a Christian metaphor of sorts, where Jesus was born to a world that didn’t appreciate him, and he died for the sins of all the others. In that this new being died for their sins, even though they didn’t know what they were doing. Here they have this naked thing, who’s been born of Mother Earth and God, and they….

And they don’t even realize it.

And they don’t realize it and they beat him and kill him. And he begets the rest.

I think that’s very beautiful what you just said. And I don’t think that’s off the mark. But the thing is, you go not just to the mythology of Jesus, but also to Isis and Osiris, and you go back to Attus and Adonis, and it goes way back to be the pre-Christian ideas and, then certainly with the idea of creation as it exists in the Hebraic sense, in the Old Testament. It’s just these themes of sacrifice and resurrection are in every culture and every age. And they’re important themes. And I love art that is charged with both pathos and mythos. And you see it in Arnold Böcklin’s paintings. You see it in a lot of expressionist and symbolist paintings. And you certainly see it in the romantic paintings, and in the Romantic poets like Byron and Shelley. And in Goethe, the German poet. All these voices from the past definitely have influenced me to a very profound degree. And I feel like–that being inspired by these minds and by these works of art from hundreds of years ago, I imbue it into my own blood and invigorate it with a new life and put it out into a new–in a new way, through film and–through the films that I’m making.

Also the elements in both of your films–regarding themes of sacrifice and all that–there’s also sort of a haunting feeling throughout both of the films. I think that what’s happening in “Begotten” isn’t entirely pleasant. It’s interesting. It’s always sort of fascinating, but it’s also upsetting.

No. Absolutely.

Much in the way that any martyr, who has to suffer for others’ sins or whatever–it’s not the most pleasant thing ever. And same with “Shadow of the Vampire”, too. It’s always super-interesting, and a reflection on things you said about current filmmaking. But it’s also kind of haunting. These people are disappearing, and is Schreck really killing them? And then you start to think, “He really is a vampire. Or at least he thinks he is. And that’s enough.”

I can’t tell you how much I appreciate you seeing “Begotten”, and having an appreciation of that film. ‘Cause I love that film, really. I never thought about, “Oh, I’m going to go to Hollywood with “Begotten” and I’m going to be a big movie director.” It was the kind of thing where I made “Begotten” just purely like a fever. It was like a fever that hit me, and then, when the film was done, the fever broke, and it passed. It was somewhat of an obsession and a great, profound love, making that film. And I learn something new from that film every time that I see it. I don’t feel like its maker. I feel like it’s got its own life force, and every time I see the film, I’m learning something new from it.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

“Antony Narto”? Antonin Artaud, surely. XD

Exactly. Thanks for pointing this out. He was a great theorist.

Arnold Bröcklin, not Arnold Bachland

good catch , we fixed his reference

Arriflex camera, not aeroflex