SYNOPSIS:

“The evil Trade Federation led by Nute Gunray is planning to take over the peaceful world of Naboo. Jedi Knights Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi are sent to confront the leaders. But not everything goes to plan. The two Jedi escape, and along with their new Gungan friend, Jar Jar Binks head to Naboo to warn Queen Amidala, but droids have already started to capture Naboo and the Queen is not safe there. Eventually, they land on Tatooine, where they become friends with a young boy known as Anakin Skywalker. Qui-Gon is curious about the boy, and sees a bright future for him. The group must now find a way of getting to Coruscant and to finally solve this trade dispute, but there is someone else hiding in the shadows. Are the Sith really extinct? Is the Queen really who she says she is? And what’s so special about this young boy?” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

In the old days of movie serials, audiences would leave cinemas in a heightened state of anticipation, a state brought on by a cliffhanger ending and the promise of a resolution in next week’s episode. For sixteen years fans of the original Star Wars trilogy had been in a similar state of mind except, in this case, the question was not, “How will it end?” but rather, “How did it begin?” From the first moments of Star Wars IV A New Hope (1977) it was evident that the narrative was picking up not at the beginning of the story, but at its middle. A sense of history and a struggle long in progress endowed every frame of the film and its successors, Star Wars V The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Star Wars VI Return Of The Jedi (1983). What went before was a mystery and, even as the final movie in that original trilogy came to a victorious close, as the end credits rolled, countless questions lingered. What terrible events had transformed Luke’s father, Anakin Skywalker, from a Jedi knight into the evil Sith lord, Darth Vader? Why had he turned to the dark side? What had started the fierce war between the evil empire and the galactic republic? How had the empire been born? How was the resistance launched and by whom?

With the release of Star Wars I The Phantom Menace (1999), some questions surrounding the saga’s origins were finally answered. That there would be another trilogy of films to tell that backstory was never in question. Star Wars creator George Lucas had promised from the beginning that episodes I, II and III would follow production of the original IV, V and VI, he just never said when. As years passed and Lucas remained vague on the subject, Star Wars fans were left to wonder, “What the hell is he waiting for?!” What he was waiting for, in fact, was the development of visual effects technologies that would allow him to realise, without compromise, the films he had always imagined. Frustration with the laborious and achingly slow filmmaking process in general, and with visual effects technology in particular, had plagued Lucas throughout the making of the original trilogy and, even though those had possessed special effects that were nothing less than spectacular for its time, all three were, in Lucas’s mind, shadows of the films he had really wanted to make. Until the technology had evolved to a point where his vision could be realised in totality, the director was content to put the new Star Wars trilogy on the back-burner and concentrate his energies on other projects. Lucas would wait. But in the interim, the entrepreneurial filmmaker was hardly a passive observer of effects trends – he was, in fact, the field’s most ardent and aggressive promoter.

As early as the late seventies – when the film industry was still contentedly working in the realm of photochemistry – Lucas developed a small in-house digital department at Industrial Light & Magic, his venerated visual effects facility, and encouraged that handful of computer wizards to stretch the envelope of digital effects for feature films both artistically and technologically. For the next two decades Lucas kept his foot firmly planted at the backside of CG development, and the result was a digital department that grew exponentially. Computer artists and workstations soon took over most of the square footage of the ever-expanding ILM facility, setting the standard for digital effects in the process. First came Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) and its stained-glass man, then came the watery pseudopod of The Abyss (1989). As major strides were made in the field, ILM went on to produce the liquid metal man in Terminator 2 Judgment Day (1991) then, astonishingly, the dinosaurs of Jurassic Park (1993), the ghostly apparitions of Casper (1995), the dragon in Dragonheart (1996) and the even more photorealistic dinosaurs in The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997).

The special edition updates of the Star Wars trilogy pushed the learning curve even further and served as an unofficial testing ground for episodes I, II and III. Finally, Lucas felt confident that digital technology had evolved to a point where the making of his new Star Wars films was feasible, and began writing the first script of the new trilogy in November 1994, adapting his own original fifteen-page outline that was written back in 1976. Its working title was The Beginning but was retitled The Phantom Menace, in reference to Palpatine hiding his true identity as an evil Sith Lord. Bigger budgets and state-of-the-art digital effects opened up possibilities which allowed Lucas to think on a much grander scale, which is what he always wanted Star Wars to be. Ron Howard, Robert Zemeckis and Steven Spielberg were all approached to direct The Phantom Menace – all three found the project too daunting and insisted that Lucas should direct the film himself. So he did.

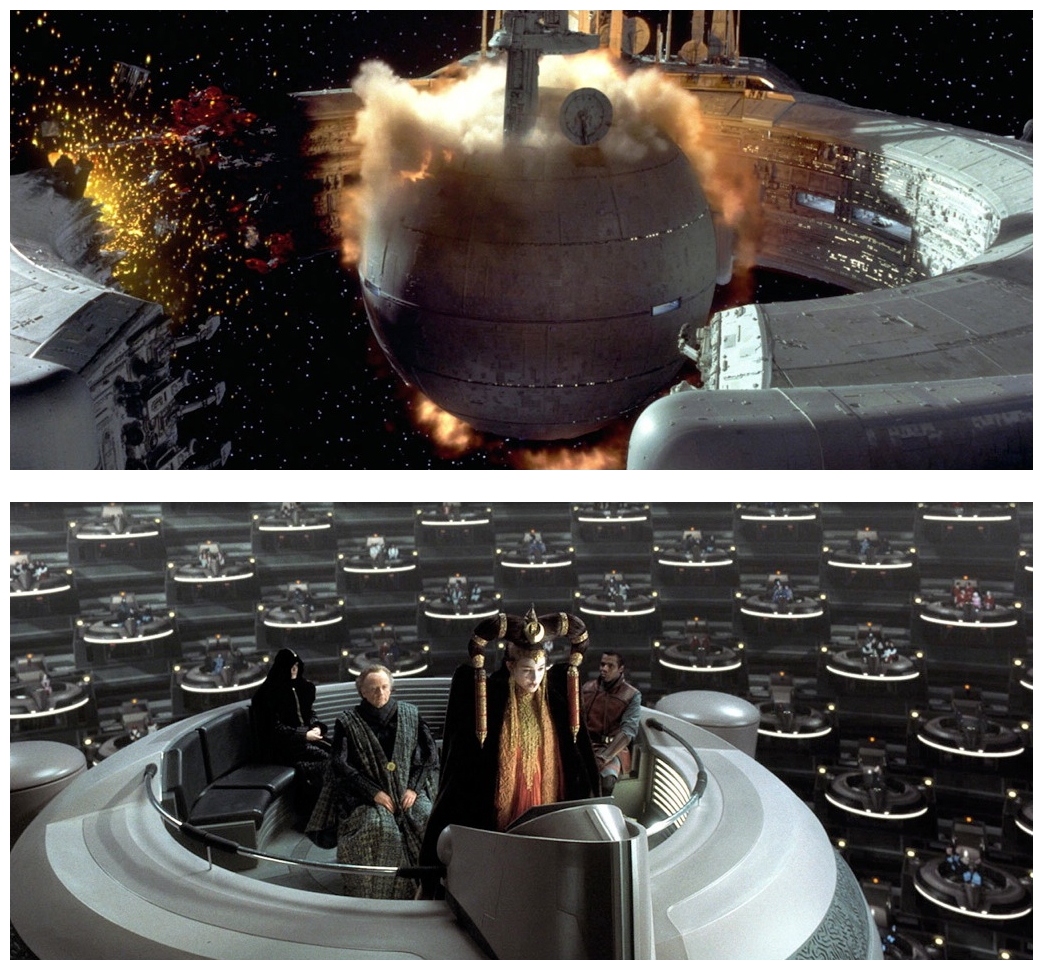

The Trade Federation have blockaded the planet Naboo in preparation for a full-scale invasion, so Jedi Master Qui-Gon Jinn (Liam Neeson) and his apprentice Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor) are sent to negotiate with the Federation Viceroy Nute Gunray (Silas Carson). Gunray’s secret advisor Darth Sidious orders the Viceroy to have the Jedi killed and begin the invasion of the battle droids. The Jedi escape and flee to Naboo during the invasion, when Qui-Gon saves a Gungan outcast named Jar Jar Binks (Ahmed Best) from certain death. Binks leads the Jedi to the underwater Gungan capital city. The Jedi are unable to convince Gungan leader Boss Nass (Brian Blessed) to help the people of Naboo, though Nass does offer them transportation to Theed, the capital city on the surface. When they get there they rescue Queen Padmé Amidala (Natalie Portman), escape in her all-chrome royal starship and head for the Republic capital planet Coruscant. Unfortunately, the ship is damaged and they land for repairs on the desert planet Tatooine. Qui-Gon, Binks, R2-D2 (Kenny Baker) and Padmé (disguised as one of her handmaidens) intend to purchase new parts at a junk shop. They meet shop owner Watto (Andy Secombe) and his nine-year-old slave Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd) who happens to be a pretty good pilot and engineer, and has even built a protocol droid called C-3PO (Anthony Daniels) from spare parts.

Qui-Gon is convinced that Anakin is the ‘chosen one’ of the Jedi prophecy who will bring balance to the Force. After winning a spectacular pod race, Anakin joins Qui-Gon to be trained as a Jedi, leaving behind his mother Shmi (Pernilla August). Before leaving Tatooine, Qui-Gon encounters Darth Maul (Ray Park), an apprentice of Darth Sidious, sent to capture Amidala. A duel ensues, but Qui-Gon quickly disengages and escapes on board the starship. Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan escort Amidala to Coruscant so she can plead her case to the Galactic Senate. Qui-Gon asks Yoda (Frank Oz) permission to train Anakin as a Jedi, but is refused because it is believed the boy might be vulnerable to the dark side of the Force. Qui-Gon ignores Yoda’s advice and trains Anakin anyway. Meanwhile, Naboo’s Senator Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid) persuades Amidala to make a vote of no confidence in order to elect a more capable chancellor. She succeeds in pushing through the vote, but Senate corruption frustrates her and she decides to return to Naboo. Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan are ordered to accompany her, as well as to confirm the possible return of the evil Sith Lords, assumed long dead.

The story concludes with five simultaneous, ongoing plots, one leading to another. The central plot is Palpatine’s intent to become Chancellor, which leads to the Trade Federation’s attack on Naboo, the Jedi being sent there, Anakin being met along the way, and the rise of the Sith Lords. As with the original trilogy, Lucas wanted The Phantom Menace to illustrate several different themes. Duality is a frequent theme (a queen disguised as a handmaiden, Palpatine plays both sides of the war) and balance is frequently suggested (Anakin might be the chosen one to bring balance to the Force). Lucas: “Anakin needed to have a mother, Obi-Wan needed a Master, Darth Sidious needed an apprentice. Without this interaction and dialogue you wouldn’t have drama.” Star Wars I The Phantom Menace was arguably the most hyped film of the last century and has been put under the microscope and looked at in a million different ways. There were disenchanted fans who dismissed the film no matter what, many put off by the marketing. Some fans prejudged the movie and then strutted about saying, “I told you so.” There were also diehard fans who were impossible to disappoint. Arguably, the plot has more substance than parts IV, V and VI combined, and the intricacies of politics, the metaphysical properties of the force, the nature of bondage and the messianic innuendos are potentially mind-blowing.

Lucas cherry-picked from dozens of popular cultural references to create Star Wars, of course, but his three primary influences were Flash Gordon serials, the Dune trilogy, and the Lord Of The Rings trilogy. It’s in The Phantom Menace we get a taste of the space-politics of Dune, resulting in some long passages of dialogue in front of windows between action scenes. Speaking of which, the most exciting sequence in The Phantom Menace is also the most derivative – the pod race is a cinematic tradition that goes back to the chariot race in Ben-Hur, and I’m not just talking movies. Even the original 1899 stage version featured the chariot race, with real horses pulling real chariots on a gigantic treadmill! The performances in The Phantom Menace are solid all around, with the glaring exception of young (and inexperienced) Jake Lloyd. Neeson and McGregor show a great deal of restraint, which some viewers might perceive as flat, but they’re playing martial-arts monks, after all, there are no sexy roguish pirates to be found in this particular chapter. The sets, costumes, sound and visual effects are all beautifully realised, all of which were nominated for Oscars, all of which were taken by The Matrix (1999) which is a pity, because the fight scenes The Phantom Menace involved fewer special effects. Composer John Williams outdoes himself again, particularly during the final battle and parade on Naboo.

It’s not all good news though. There are some terrible pacing problems, with action interrupted by characters talking while sitting in round rooms looking out windows, making it feel somewhat unnatural. Something bothered me about Anakin’s progress and success, something a little more haphazard than the supernatural workings of the Force. We are told about midi-chlorians, intelligent microscopic life forms that live symbiotically inside the cells of all living things and, in sufficient numbers, they allow their host to detect the pervasive energy field known as the Force. This immediately reminded me of the Red Dwarf episode Quarantine involving a virus that gives the infected person good luck and, judging from his amazing series of fortunate events, the Force is obviously strong with Jar Jar Binks (which brought about the amusing fan rumour that Binks is actually a Sith Lord in the making). As I mentioned before, young Jake Lloyd was not a good choice to play such a pivotal role and the scenes between him and Natalie Portman feel awkward.

Apparently some viewers were offended by the use of different accents and dialects – Jamaican (Binks), Asian (Gunray), Jewish (Watto) – I never gave it a second thought, although Binks’ voice gets very irritating very quickly. On one hand I understand Lucas’ motivations for inserting such stereotypical characters – Star Wars is first and foremost a tribute to cinematic traditions – but on the other hand it appears like a simple lack of imagination. James Berardinelli: “Looking at the big picture, in spite of all its flaws, The Phantom Menace is still among the best ‘bang for a buck’ fun that can be had in a movie theatre. It isn’t as fresh as the original Star Wars nor does it have the thematic richness and narrative complexity of The Empire Strikes Back, but it is a distinct improvement over Return Of The Jedi. In fact, after Return Of The Jedi, I didn’t have a burning desire to return to this galaxy far, far away but, with The Phantom Menace, Lucas has revived my interest.” Andrew Johnston: “Let’s face it, no film could ever match the expectations some have for Episode I The Phantom Menace. Which isn’t to say it’s a disappointment, on the contrary, it’s awesomely entertaining, provided you accept it on its own terms. Like the original film, it’s a Boy’s Own adventure yarn with a corny but irresistible spiritual subtext. The effects and production design are stunning, but they always serve the story, not the other way around.”

I sincerely believe that history will smile on this movie as the story progresses in the sequels Star Wars II Attack Of The Clones (2002) and Star Wars III Revenge Of The Sith (2005) and we become more familiar with some of the new concepts introduced The Phantom Menace, as well as the new trilogy Star Wars VII The Force Awakens (2015), Star Wars VIII The Last Jedi (2017) and Star Wars IX (2019). J.J. Abrams directed The Force Awakens, then Rian Johnson was given the job of writing and directing The Last Jedi, and he’s writing and probably directing Episode IX. Johnson is not a man you can put in a neat little box. His time-travel thriller Looper (2012) and his involvement in the Star Wars franchise might label him as some sort of science fiction mastermind, but a glance at his back-catalogue unravels that thread quickly enough. The only really cohesive feature of Johnson’s previous three films – Brick (2005), The Brothers Bloom (2008), Looper (2012) – is that they are laden with subtext, but that’s another story for another time. I look forward to your company next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Star Wars I The Phantom Menace (1999)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews