In 1928, Carl Laemmle Senior made his son, Carl Laemmle Junior, head of Universal Pictures as a 21st birthday present. Woo hoo! Universal already had a reputation for nepotism – at one point, seventy of Carl Senior’s relatives were supposedly on the payroll. Many of them were nephews, resulting in Carl Senior being known around the studios as Uncle Carl. If you’re wondering how to pronounce the surname, Ogden Nash once rhymed, “Uncle Carl Laemmle, has a very large faemmle.” To his credit, Carl Junior persuaded his father to bring Universal up-to-date. He bought and built theatres, converted the studio for sound films, and made several forays into high-quality production. His early efforts included Showboat (1929), the lavish musical Broadway (1929) which included Technicolor sequences, and All Quiet On The Western Front (1930), which won Best Picture Oscar that year.

In 1928, Carl Laemmle Senior made his son, Carl Laemmle Junior, head of Universal Pictures as a 21st birthday present. Woo hoo! Universal already had a reputation for nepotism – at one point, seventy of Carl Senior’s relatives were supposedly on the payroll. Many of them were nephews, resulting in Carl Senior being known around the studios as Uncle Carl. If you’re wondering how to pronounce the surname, Ogden Nash once rhymed, “Uncle Carl Laemmle, has a very large faemmle.” To his credit, Carl Junior persuaded his father to bring Universal up-to-date. He bought and built theatres, converted the studio for sound films, and made several forays into high-quality production. His early efforts included Showboat (1929), the lavish musical Broadway (1929) which included Technicolor sequences, and All Quiet On The Western Front (1930), which won Best Picture Oscar that year.

Carl Junior also created a successful niche for the studio, beginning a long-running series of monster movies, among them Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931) and The Mummy (1932). Despite the Great Depression, Carl Junior produced massive successes for the studio with Dracula directed by Tod Browning and Frankenstein directed by James Whale. The success of these two movies launched the careers of both Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, and ushered in a new genre of American cinema. These films also provided steady work for a number of genre actors including Lionel Atwill, Dwight Frye, Edward Van Sloan and John Carradine. Other regulars involved were make-up artists Jack Pierce and the Westmores, and composers Hans Salter and Frank Skinner. Many of the horror genre’s most well-known conventions (creaking staircases, cobwebs, swirling mist and torch-wielding villagers) originated from these films and those that followed.

Carl Junior also created a successful niche for the studio, beginning a long-running series of monster movies, among them Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931) and The Mummy (1932). Despite the Great Depression, Carl Junior produced massive successes for the studio with Dracula directed by Tod Browning and Frankenstein directed by James Whale. The success of these two movies launched the careers of both Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, and ushered in a new genre of American cinema. These films also provided steady work for a number of genre actors including Lionel Atwill, Dwight Frye, Edward Van Sloan and John Carradine. Other regulars involved were make-up artists Jack Pierce and the Westmores, and composers Hans Salter and Frank Skinner. Many of the horror genre’s most well-known conventions (creaking staircases, cobwebs, swirling mist and torch-wielding villagers) originated from these films and those that followed.

Dracula (1931) was originally intended as a vehicle for Lon Chaney Senior, who sadly passed away, so Universal turned to the relatively unknown Bela Lugosi, who was very familiar with the role following a two-year stint in the stage production. This opportunity for the Hungarian actor would not only change his life, but would forever associate Lugosi with Dracula (and later Ed Wood). Although no-where near as chilling as the silent Nosferatu (1922), which remains an unparalleled masterpiece, the 1931 version introduced the voice and the look that has become common practice. A frenzied Renfield (Dwight Frye) and some wonderful camera work from Carl Freund also deserve kudos. Fangs for the memories.

Dracula (1931) was originally intended as a vehicle for Lon Chaney Senior, who sadly passed away, so Universal turned to the relatively unknown Bela Lugosi, who was very familiar with the role following a two-year stint in the stage production. This opportunity for the Hungarian actor would not only change his life, but would forever associate Lugosi with Dracula (and later Ed Wood). Although no-where near as chilling as the silent Nosferatu (1922), which remains an unparalleled masterpiece, the 1931 version introduced the voice and the look that has become common practice. A frenzied Renfield (Dwight Frye) and some wonderful camera work from Carl Freund also deserve kudos. Fangs for the memories.

When viewed in its original censorship-free version, James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) and Boris Karloff’s portrayal of the greatest monster of all-time, combine to deliver the definitive treatment of Mary Shelley’s sympathetic tale. Whale’s film amplifies the torment of a man struggling with his feverish dreams of creating life and the agonising existence of his creation – a monster. Brought to life by the obsessed Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive), our gentle giant is tormented and ill-treated, not only by the scientist’s side-kick Fritz (Dwight Frye) but by his all-too-immediate role in society. Portrayed as the villain, Karloff brings humanity and empathy to the monster. In one of the most controversial scenes, we see the giant play like a bewildered child, throwing flowers into a lake with a young girl only to misunderstand and all too often misjudged by the society that created him, he is hunted as the savage killer he has become. Karloff’s greatest and most famous role, and perhaps the most fantastic use of monster makeup of all time ensure that James Whale’s Frankenstein remains the best of them all.

When viewed in its original censorship-free version, James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) and Boris Karloff’s portrayal of the greatest monster of all-time, combine to deliver the definitive treatment of Mary Shelley’s sympathetic tale. Whale’s film amplifies the torment of a man struggling with his feverish dreams of creating life and the agonising existence of his creation – a monster. Brought to life by the obsessed Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive), our gentle giant is tormented and ill-treated, not only by the scientist’s side-kick Fritz (Dwight Frye) but by his all-too-immediate role in society. Portrayed as the villain, Karloff brings humanity and empathy to the monster. In one of the most controversial scenes, we see the giant play like a bewildered child, throwing flowers into a lake with a young girl only to misunderstand and all too often misjudged by the society that created him, he is hunted as the savage killer he has become. Karloff’s greatest and most famous role, and perhaps the most fantastic use of monster makeup of all time ensure that James Whale’s Frankenstein remains the best of them all.

The Mummy (1932) may not be as action-packed or as lavish as the 1999 Stephen Sommers remake starring Arnold Vosloo, but the 1932 effort with monster-maestro Boris Karloff certainly deserves a place alongside Dracula and Frankenstein in the Universal pantheon of timeless horror icons – but only just. Karloff again manages to bring to the screen an air of mesmerising eeriness and the effortless quality of captivating the viewer in his portrayal of the mummy Imhotep, searching for his reincarnated princess. Sadly, the film lacks any real suspense and all too often some absurd dialogue undermines this rather dull effort. Still, Jack Pierce’s incredible makeup, Karloff’s indomitable presence and the popular topic of reincarnation justifies its place as a classic. Despite her faults, everybody still loves their Mummy.

The Mummy (1932) may not be as action-packed or as lavish as the 1999 Stephen Sommers remake starring Arnold Vosloo, but the 1932 effort with monster-maestro Boris Karloff certainly deserves a place alongside Dracula and Frankenstein in the Universal pantheon of timeless horror icons – but only just. Karloff again manages to bring to the screen an air of mesmerising eeriness and the effortless quality of captivating the viewer in his portrayal of the mummy Imhotep, searching for his reincarnated princess. Sadly, the film lacks any real suspense and all too often some absurd dialogue undermines this rather dull effort. Still, Jack Pierce’s incredible makeup, Karloff’s indomitable presence and the popular topic of reincarnation justifies its place as a classic. Despite her faults, everybody still loves their Mummy.

Hats must be taken off to any film that boasts a lead role that you can’t see. Claude Rains‘ bandage-clad portrayal of The Invisible Man (1933) is unparalleled when it comes to invisible men. James Whale’s version of the H.G. Wells classic remains the most iconic, blending science fiction, the supernatural, and groundbreaking special effects with sly black comedy and suspense. It should not be forgotten, however, that Claude Rains’ transparent role is pure evil, a man consumed by the desire to have the world groveling at his feet – a contemptuous being that wreaks havoc and thrives on mass destruction and anarchy. The only glimmer of humanity emerges in his love for Flora (Gloria Stuart), but this isn’t enough to prevent his inevitable self-destruction. He’s mad, he’s bad and he’s invisible! A true classic not to be missed.

Hats must be taken off to any film that boasts a lead role that you can’t see. Claude Rains‘ bandage-clad portrayal of The Invisible Man (1933) is unparalleled when it comes to invisible men. James Whale’s version of the H.G. Wells classic remains the most iconic, blending science fiction, the supernatural, and groundbreaking special effects with sly black comedy and suspense. It should not be forgotten, however, that Claude Rains’ transparent role is pure evil, a man consumed by the desire to have the world groveling at his feet – a contemptuous being that wreaks havoc and thrives on mass destruction and anarchy. The only glimmer of humanity emerges in his love for Flora (Gloria Stuart), but this isn’t enough to prevent his inevitable self-destruction. He’s mad, he’s bad and he’s invisible! A true classic not to be missed.

James Whale initially rejected the thought of a sequel to Frankenstein, but with the vast investment in place from Universal there was very little choice – thankfully. More than just a sequel, The Bride Of Frankenstein (1935) is a reflection of James Whale, as his own personality is injected into the film producing a wonderful blend of humour and terror. By far the more superior offering than the first Frankenstein, the sequel really brings the monster to life. It is Karloff the actor that stands tall as he allows us to warm to the monster, feeling compassion and sadness for a creature that just wants to love and to be loved. The real villain emerges in the form of the horrendous Doctor Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger). There are strokes of genius from both Whale and Karloff, especially as we see the all-drinking, all-smoking, all-dancing monster find solace with a blind hermit. It’s even more apparent in The Bride Of Frankenstein at how misunderstood our monster really is, and how he has become a nightmare in broad daylight. A film that gave us the first and perhaps only iconic female monster, provided a joyous musical score, injected the genre with camp black comedy, and above all, gave us one of the greatest horror films of all-time.

James Whale initially rejected the thought of a sequel to Frankenstein, but with the vast investment in place from Universal there was very little choice – thankfully. More than just a sequel, The Bride Of Frankenstein (1935) is a reflection of James Whale, as his own personality is injected into the film producing a wonderful blend of humour and terror. By far the more superior offering than the first Frankenstein, the sequel really brings the monster to life. It is Karloff the actor that stands tall as he allows us to warm to the monster, feeling compassion and sadness for a creature that just wants to love and to be loved. The real villain emerges in the form of the horrendous Doctor Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger). There are strokes of genius from both Whale and Karloff, especially as we see the all-drinking, all-smoking, all-dancing monster find solace with a blind hermit. It’s even more apparent in The Bride Of Frankenstein at how misunderstood our monster really is, and how he has become a nightmare in broad daylight. A film that gave us the first and perhaps only iconic female monster, provided a joyous musical score, injected the genre with camp black comedy, and above all, gave us one of the greatest horror films of all-time.

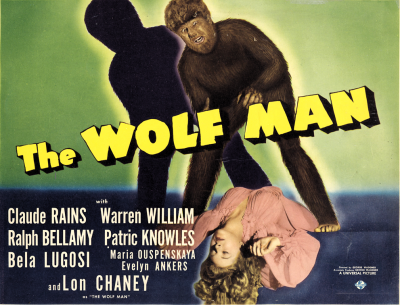

“Even a man who is pure of heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf man when the wolfbane blooms and the Autumn moon is bright.” George Waggners’s The Wolf Man (1941) introduced the mythology of the werewolf in a film that was the signature role for Lon Chaney Junior. This classic tale has since visited the big screen on so many occasions and incarnations, but few compare to this groundbreaking film with its simplistic man-to-wolf transformation, dense atmosphere and literate script. The all too brief inclusion of Bela Lugosi only adds to the reputation of this granddaddy of all werewolf films. The DVD I recently viewed featured interviews with original screenwriter Curt Siodmak, An American Werewolf In London (1981) director John Landis and makeup maestro Rick Baker. Avoid the full moon, perhaps, but don’t avoid the special features!

“Even a man who is pure of heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf man when the wolfbane blooms and the Autumn moon is bright.” George Waggners’s The Wolf Man (1941) introduced the mythology of the werewolf in a film that was the signature role for Lon Chaney Junior. This classic tale has since visited the big screen on so many occasions and incarnations, but few compare to this groundbreaking film with its simplistic man-to-wolf transformation, dense atmosphere and literate script. The all too brief inclusion of Bela Lugosi only adds to the reputation of this granddaddy of all werewolf films. The DVD I recently viewed featured interviews with original screenwriter Curt Siodmak, An American Werewolf In London (1981) director John Landis and makeup maestro Rick Baker. Avoid the full moon, perhaps, but don’t avoid the special features!

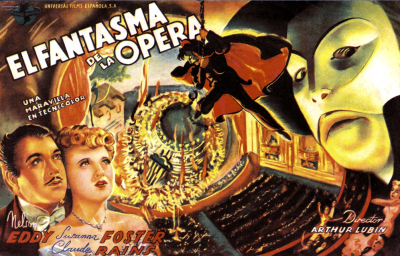

What the ambitious remake of The Phantom Of The Opera (1943) loses in suspense, it wins in other areas. Taking full advantage of the emergence of film sound and the spectacular arrival of Technicolor, Claude Rains’ masked man clearly distinguishes itself as the most lavish of all versions. Adapted from the 1925 silent screen version and from one of Gaston Leroux’s most famous novels, the 1943 Phantom brings a little more humanity to the romantic tale of a beauty and her beast. Rains revels in the role of a man in pursuit of his passions who, after a misunderstanding, is disfigured and forced to take refuge in the subterranean underworld of the Paris sewer system. Unfortunately, the extravagant use of sets and costumes, and the overuse of operatic arias significantly dilutes the suspense quotient, and the comedic pairing of Nelson Eddy and Edgar Barrier doesn’t help. Still, it’s far better than Andrew Lloyd Webber’s attempt! The opera house might be the star, but Rains’ Phantom Of The Opera remains one of the best.

What the ambitious remake of The Phantom Of The Opera (1943) loses in suspense, it wins in other areas. Taking full advantage of the emergence of film sound and the spectacular arrival of Technicolor, Claude Rains’ masked man clearly distinguishes itself as the most lavish of all versions. Adapted from the 1925 silent screen version and from one of Gaston Leroux’s most famous novels, the 1943 Phantom brings a little more humanity to the romantic tale of a beauty and her beast. Rains revels in the role of a man in pursuit of his passions who, after a misunderstanding, is disfigured and forced to take refuge in the subterranean underworld of the Paris sewer system. Unfortunately, the extravagant use of sets and costumes, and the overuse of operatic arias significantly dilutes the suspense quotient, and the comedic pairing of Nelson Eddy and Edgar Barrier doesn’t help. Still, it’s far better than Andrew Lloyd Webber’s attempt! The opera house might be the star, but Rains’ Phantom Of The Opera remains one of the best.

A decade later, Jack Arnold’s subtext-rich Creature From The Black Lagoon (1953) originally made a big splash with audiences, but who could say no to a highly aroused gill-man or the lure of the first underwater 3-D movie? Boldly opening with no less than the creation of the Earth and a highly suspect explanation concerning our lineage to the undersea realm, it’s soon jungle river cruise time with deliciously sexy Julie Adams (looking like a fifties Jennifer Connelly) understandably becoming the object of desire for the rather randy titular Creature. Their famous erotically-charged swim together has had film historians reaching for cold flannels for well over fifty years. Black Lagoon? More like Blue Lagoon if you ask me!

A decade later, Jack Arnold’s subtext-rich Creature From The Black Lagoon (1953) originally made a big splash with audiences, but who could say no to a highly aroused gill-man or the lure of the first underwater 3-D movie? Boldly opening with no less than the creation of the Earth and a highly suspect explanation concerning our lineage to the undersea realm, it’s soon jungle river cruise time with deliciously sexy Julie Adams (looking like a fifties Jennifer Connelly) understandably becoming the object of desire for the rather randy titular Creature. Their famous erotically-charged swim together has had film historians reaching for cold flannels for well over fifty years. Black Lagoon? More like Blue Lagoon if you ask me!

With the success of Creature From The Black Lagoon the revived Universal Horror franchise would gain a new generation of fans. The original movies such as Dracula and Frankenstein were re-released as double features in many theatres, before eventually appearing on syndicated television in 1957. Soon dedicated magazines such as Famous Monsters Of Filmland and websites like Horror News would help propel these movies into lasting infamy. It’s terribly important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because my horoscope specifically said that unless you read all our reviews, all life on Earth would cease to exist! Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but it sounded so convincing, I feel you’d best not take the risk. So have a good weekend, and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

With the success of Creature From The Black Lagoon the revived Universal Horror franchise would gain a new generation of fans. The original movies such as Dracula and Frankenstein were re-released as double features in many theatres, before eventually appearing on syndicated television in 1957. Soon dedicated magazines such as Famous Monsters Of Filmland and websites like Horror News would help propel these movies into lasting infamy. It’s terribly important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because my horoscope specifically said that unless you read all our reviews, all life on Earth would cease to exist! Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but it sounded so convincing, I feel you’d best not take the risk. So have a good weekend, and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews