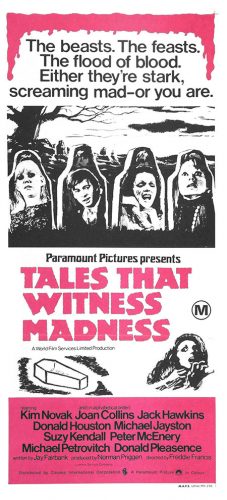

SYNOPSIS:

An eccentric psychiatrist introduces a colleague to four particularly bizarre cases, each being the subject of a short story. There’s a boy and his lethal imaginary friend, an antique dealer who slips back and forth in time, a man who becomes romantically involved with a tree stump, and a Hawaiian author planning a very ghoulish luau.

REVIEW:

Since 1924’s Waxworks, anthology films have been a horror genre staple, although 1945’s Dead of Night truly ignited their popularity. Hammer Films long-time rival Amicus Productions perfected the multi story film, producing eight anthologies including Torture Garden, The House That Dripped Blood and Tales From the Crypt. The format allowed Amicus to hire marquee value actors for only a few days. These actors loved filling short gaps in their schedule with lucratively paying work. It was a profitable formula. But Amicus didn’t own a patent on these anthologies so other companies tried their hand. Some like Mario Bava’s Black Sabbath were brilliant while others, like today’s film, Tales That Witness Madness, missed the boat.

It’s sad because Tales That Witness Madness had the ingredients to be a winner. First and foremost, the producers hired Freddie Francis, an Oscar winning cinematographer and veteran director of British horror films for Hammer, Amicus and Tigon. Francis had just directed the EC Comics adaptation Tales From the Crypt for Amicus, which became their most financially successful and critically praised release. Tales That Witness Madness also assembled a solid cast including Donald Pleasence, Joan Collins (another Tales From the Crypt alumni) and Kim Novak, who’d been absent from movie screens for five years.

All they needed was some snappy horror stories with twist endings to complete the package. But instead of turning to aces like Robert Bloch or Richard Matheson, the producers inexplicably chose actress Jennifer Jayne as screenwriter—and that’s where the problem lies. Jayne’s only previous screenwriting credit was 1972’s still unreleased Ringo Starr vehicle Son of Dracula. Starr, who was also the film’s producer, was so unhappy with Son of Dracula that he tried to convince Monty Python’s Graham Chapman to write and record entirely new dialogue to dub over the flat script— à la 1969’s notorious post dubbed skin flick Dracula, the Dirty Old Man. Sadly, Jayne’s script for Tales That Witness Madness shows little improvement.

The first story revolves around a boy and his imaginary friend, who happens to be a tiger, named (no, not Hobbes) Mr. Tiger. It starts out strong but continuously telegraphs the ending for the entire second half, ruining any chance of surprise. The finale still manages a few gruesome moments, whetting the audience’s appetite for more shocks to come.

Unfortunately, the second story, Penny Farthing, sucks the wind out the movie’s sails. It’s about an antique dealer (Peter McEnery) who inherits a vintage bicycle and a photograph of his unfortunately named Uncle Albert. The segment is only memorable for the unintentionally hilarious transforming photograph of Uncle Albert, which director Francis incessantly cuts to. Penny Farthing’s unintentional humor raises the question of whether Jayne was actually trying to write a very dark and dry (to the point of arid) comedy. If so it would have been nice of her to throw in some witty dialogue, thereby letting the rest of us in on her plan.

Round three is entitled Mel. It’s the tender story of Brian (Michael Jayston), a man who falls in love with a tree stump that he affectionately names Mel. This doesn’t go over well with his wife Bella (Joan Collins) who does everything in her power to win him back. But, alas, he only has eyes for his tree stump. Remember, this was a pre Dynasty Joan Collins, when her feminine wiles were fresh and mostly real, so her husband’s really missing out. Brian’s behavior makes you wonder what mysterious force possesses this hunk of wood. Unfortunately, the script doesn’t offer any backstory on the bewitching tree stump or attempt to explain its power over Brian … he’s just a weird guy in love with a tree stump. This segment does have one of the film’s only memorable visuals—a hallucinatory scene of Joan Collins being stripped and ravaged by the living tree, predating a similar scene in The Evil Dead. Joan Collins’ photo-double’s briefly glimpsed breasts were probably thrown in to assure an R rating.

This rampaging tree scene raises a major issue. Why does a film directed by a gifted cinematographer have such drab visuals? Francis’ previous anthology Tales From the Crypt is packed with creepy and memorable moments. Remember that razor blade lined hallway lit by a swinging bare light bulb or the cadaverous psycho Santa peering through the windows? Chilling stuff. In contrast, Tales That Witness Madness has nothing that sticks in your mind. I suspect that Francis felt he had little to work with dramatically and therefore lapsed into being competent and professional—a sad waste of talent.

And finally we come to Luau, the tale of a Hawaiian author (Michael Petrovich) paying a visit to his literary agent (a somnambulistic Kim Novak) and her rebellious but virginal teenage daughter (Mary Tamm). The author has a dark, ulterior motive for his visit involving a gruesome island religious rite that will climax during a traditional Hawaiian luau. If you’ve seen HG Lewis’ campy gore flick Blood Feast (1963) you already know where this story’s headed. This segment showed potential, only to squander it by being overlong and inserting island flashbacks that intentionally spoil an already predictable ending.

This leaves us with the film’s wraparound segments starring the always entertaining Donald Pleasence as a psychiatrist attempting to discover the roots of four patients’ delusions. These kind of wraparound stories with their charmingly predictable revelations are an anthology film tradition. Even though you’ve already figured out that Tales From the Crypt’s Sir Ralph Richardson is Death and that Dr Terror’s House of Horror’s Peter Cushing is, well … Death, they’re still fun, satisfying bookends. Tales That Witness Madness fails to deliver on that tradition. Pleasence’s psychiatric goal and methods are never clarified and most of his dialogue isn’t exposition … it’s babbling. It’s clear the filmmakers never bothered to think the wraparounds through, and just hoped the charismatic Pleasence could sell it. To his credit, he almost pulls it off.

It may seem like I’m being overly tough on this film, after all I’m the guy who found nice things to say about Night of the Lepus. But the main reason I’m not recommending Tales That Witness Madness is because there are over a dozen better Freddie Francis movies available for your viewing pleasure. I heartily recommend 1963’s Evil of Frankenstein for its snazzy laboratory visuals or 1973’s The Creeping Flesh for its spirited Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing team up. If you’re dead set on an anthology film, Francis directed three others that are far superior to Tales That Witness Madness. Francis was a true gift to the horror genre and should be remembered for his parade of winners and not the occasional misfire.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

I didn’t know it was possible to disagree with a review on nearly every single point. Yikes.