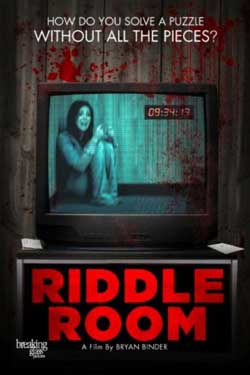

Emily Burns is being held captive in a room with no idea as to why or how she got there. Determined to escape and return to her daughter and husband, Emily discovers clues within the room that help explain what she’s doing there. They even provide clues about who she is…but will they help her escape?

REVIEW:

Riddle Room is the feature debut of director Bryan Binder and stars Marisa Stober as a kidnap victim by the name of Emily Burns. Emily has been thrown unceremoniously into plywood room with next to no furniture. On the wall, staring down on her panic is a digital clock counting down to who knows what. She is regularly visited by men in masks who give her food, whilst one in particular, wearing a burlap sack, tells her she must remember the events of 11th September at 8:30pm. At times, a television in the corner blares out the CCTV footage of her family and news reports of supposed terrorist attacks. Emily is understandably terrified and confused. But is she all she seems?

Binder should be commended for keeping the plot of Riddle Room confined within the four walls of Emily’s prison. This brevity of location certainly worked to great effect in films such as Rodrigo Cortes’ Buried, Vincenzo Natali’s Cube and, most definitely, Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs. To name but three. Unfortunately, Riddle Room just doesn’t have the same oomph as its contemporaries, and often struggles to punch above its weight.

A large issue is solely focusing on Emily, who has to carry the whole narrative. Yes, there are the men in black who visit her, and there’s even a woman who whispers to her at times, but ultimately, this is Stober’s gig. If we look at Cube, it engaged us by having its reluctant prisoners bounce off each other as they try to escape. They bicker, they cry, they fight. In Buried, Ryan Reynold’s may be the only character on screen, but he converses via phone and they even throw in an ‘action’ scene of man versus snake. Recent Aussie thriller Observance, admittedly more expansive in its scope, manages to maintain your interest, even when its hero is silent and alone.

Riddle Room struggles because an average scene is Emily wailing and gnashing her teeth, followed by a brief interlude by the man in the bag who tells her to remember, followed by more crying. Sadly, the film becomes repetitive and after prolonged exposure, Emily’s lamenting and panic becomes egregious. And honestly, a little annoying.

For all intents and purposes, Riddle Room has the narrative of a short film stretched out to breaking point. There’s strength in direction on display, but it would excel further with a compacted runtime. Running to 30, even 40, minutes would also give greater impact to the film’s ending, which, if you make it there in the film’s present form, is liable to make you hit the roof. By allowing the audience to spend too much time in the room to follow Emily’s troubling situation, it means we question the film’s resolution even more.

And perhaps, Binder knows this himself, as a massive infodump at the end has to rewrite the film’s own rules to achieve its ends. Try to imagine that final scene with Norman Bates in Psycho; staring down the camera into your very soul, his mother’s voice pleads to be found innocent. Imagine if that was followed by a scene wherein Vera Miles is seen going ‘Ha! I tricked him! I did it all!’ You’d feel utterly cheated. That’s what we have here.

I’m immediately reminded of the British slasher Deadtime which took so much time to explain why their killer was doing what he was doing, they forgot to explain how he could have been in two places at once. If you’re going to try and pull the rug from under us, don’t go into lengthy explanations about how you’re going to do it. Otherwise, you may just find us stepping to one said and chastising you for your rug pulling abilities. In the same way, I’ve completely labored the point with an iffy metaphor.

It’ll be interesting to see where Binder goes next after this for he clearly has some great ideas and a talent behind the camera. However, I would recommend getting someone else to give his screenplays the once over, so attempts at subtly don’t crumble into gaping plot holes in the dying minutes.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews