Tatsuo, a young misfit and rebel without a cause, drops out of school and gets a job as a tiler. A chance encounter leads to his involvement with the yakuza. When he attempts to leave, however, they will not allow it. Instead, he is ordered to start up a youth gang of his own. They begin small, with petty theft and extortion, progressing to assault and rape. One day, Tatsuo decides to kidnap a high school girl, whom the gang repeatedly tortures and rapes – in the house of the family of one of the boys – until her death many weeks later.

REVIEW:

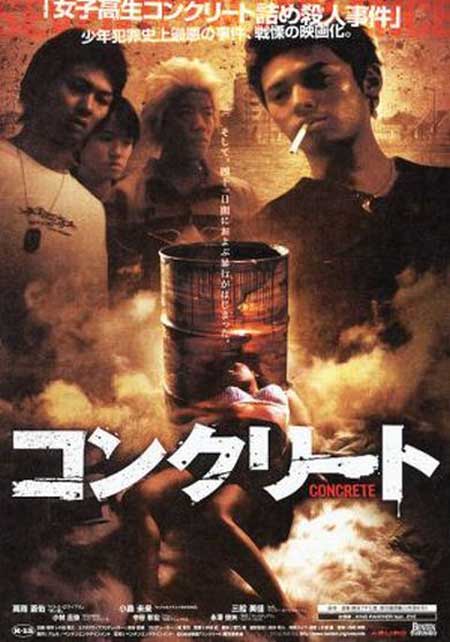

In 1988, a 17-year-old girl was abducted for a period of about six weeks in Tokyo. After suffering hideous acts of rape and torture, her juvenile captors murdered her and abandoned her body – in an oil drum filled with concrete. The case inspired further controversy in the form of public debate about the sentencing and rehabilitation of underage offenders, and inevitably became fodder for several brutal exploitation films in Japan.

The first attempt to film the story was made in 1995 by Katsuya Matsumura, whose defiantly bleak series All Night Long (consisting of six films, stretching from 1992 to 2009) focused on similarly warped and sadistic adolescent criminals. This was followed by the equally unpleasant Juvenile Crime in 1997. Years later, first-time director Hiromu Nakamura’s Concrete (aka Schoolgirl in Cement) was met with protest and outrage even before its release, in 2004, for its sensationalization of a horrific criminal case that was obviously still fresh in the nation’s memory.

While it is a nasty, repellent film – as was the case that inspired it – there are significant attempts to give some context to the main perpetrator’s dangerous malaise, without siding with him. Several social factors are introduced early in the film: the broken home, bullying at school, limited prospects and pressure from his girlfriend to make the kind of money that will enable them to get married.

In addition, parents in the film are shown to be detached from the realities of their children’s day-to-day activities; the victim’s ordeal occurs in the house of a young accomplice’s parents, who have little to no idea of the atrocities being committed right under their nose. The parents in the actual case claimed they dared not intervene because they feared their son, while in the film Tatsuo beats his mother; somehow one of the lessons he has learned about his role in society is that “girls need hitting sometimes”.

The closest the film gets to a voice of reason is Tatsuo’s girlfriend (curiously played by the daughter of Toshiro Mifune). But as upset as she is that he’s mixed up with the yakuza and still gets high sniffing glue, eventually Tatsuo is caught in a web with no chance of escape. His impressionable recruits are equally vicious, sometimes even more so. The phenomenon of violent juvenile delinquency acts like a deadly virus on other disaffected youths – although there is simply no accounting for the incredible savagery that erupts when the ringleader sets the ball rolling.

The endless series of rapes, beatings and other torture (including the use of lighter fluid to set fire to the victim’s leg) is made even more harrowing by the general lack of concern and remorse. By the end of the film, the girl’s face is reduced to a blackened, bloody pulp, and it becomes hard not to turn away. Whether shamelessly exploitive or courageously unflinching, the independently-produced Concrete is far more inflammatory than many American films that present themselves as indictments of violence perpetrated by malcontents in society’s blind spot (exceptions might include the original Last House on the Left and its unofficial 2005 remake, Chaos).

In its unapologetic portrayal of utterly loathsome young sadists and its confronting depiction of evil both mundane and merciless, Concrete could be compared to other controversial Japanese films like All Night Long or Kichiku: Banquet of the Beasts (1997), powerhouses of gritty nihilism and urban decay – with rough edges so sharp that many viewers will probably feel like slitting their wrists on them by the time the end credits start to roll.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews