SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Henry Frankenstein is a brilliant scientist who has been conducting experiments on the re-animation of lifeless bodies. He has conducted experiments on small animals and is now ready to create life in a man he has assembled from body parts he has been collecting from various sites such as graveyards or the gallows. His fiancée Elizabeth and friend Victor Moritz are worried about his health as he spends far too many hours in his laboratory on his experiments. He’s successful and the creature he’s made come to life is gentle but clearly afraid of fire. Henry’s father, Baron Frankenstein, bring his son to his senses and Henry agrees that the monster should be humanely destroyed. Before they can do so however, the monster escapes and in its innocence, kills a little girl. The villagers rise up intent on destroying the murdering creature.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

When viewed in its original censorship-free version, James Whale‘s Frankenstein (1931) and Boris Karloff‘s portrayal of the greatest monster of all-time, combine to deliver the definitive treatment of Mary Shelley‘s sympathetic tale. Whale’s film amplifies the torment of a man struggling with his feverish dreams of creating life and the agonising existence of his creation – a monster. Brought to life by the obsessed Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive), our gentle giant is tormented and ill-treated, not only by the scientist’s side-kick Fritz (Dwight Frye) but by his all-too-immediate role in society. Portrayed as the villain, Karloff brings humanity and empathy to the monster. In one of the most controversial scenes, we see the giant play like a bewildered child, throwing flowers into a lake with a young girl only to misunderstand and all too often misjudged by the society that created him, he is hunted as the savage killer he has become. Karloff’s greatest and most famous role, and perhaps the most fantastic use of monster makeup of all time ensure that James Whale’s Frankenstein remains the best of them all.

It’s also one of the great real-life melodramas to be played out under the mountains of Universal City almost a century ago. In the spring of 1931 a polite young Frenchman named Robert Florey – director of such acclaimed experimental films as The Life And Death Of 9413: A Hollywood Extra (1928), co-director of the Marx Brothers vehicle The Cocoanuts (1929), and future director of several episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits – received the green-light from Universal to adapt and possibly direct Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. He collaborated with Garrett Fort on a screenplay and directed the legendary two-reel test with Bela Lugosi as the monster which, depending on my level of intoxication, is either a sublime masterpiece or a ludicrous disaster. Nevertheless, Florey was certainly looking forward to directing Frankenstein.

It’s also one of the great real-life melodramas to be played out under the mountains of Universal City almost a century ago. In the spring of 1931 a polite young Frenchman named Robert Florey – director of such acclaimed experimental films as The Life And Death Of 9413: A Hollywood Extra (1928), co-director of the Marx Brothers vehicle The Cocoanuts (1929), and future director of several episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits – received the green-light from Universal to adapt and possibly direct Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. He collaborated with Garrett Fort on a screenplay and directed the legendary two-reel test with Bela Lugosi as the monster which, depending on my level of intoxication, is either a sublime masterpiece or a ludicrous disaster. Nevertheless, Florey was certainly looking forward to directing Frankenstein.

Enter our tall cheroot-smoking Machiavellian villain, James Whale, director of the acclaimed play and subsequent film version of Journey’s End (1930), fated to direct Universal’s most famous horror films and doomed to die in his swimming pool in 1957. Anyway, he sweeps into the office of general manager Carl Laemmle Junior, who declares Whale a genius, yanks Frankenstein away from young Florey and presents it to Whale instead. Whale goes on to glory, removing Florey’s writing credit from Frankenstein, while Florey is offered Murders In The Rue Morgue (1932) as an inferior consolation prize. This historical cinema scandal is usually told with a twist: It was widely believed that Whale”s Frankenstein was superior to anything Florey might have delivered.

Enter our tall cheroot-smoking Machiavellian villain, James Whale, director of the acclaimed play and subsequent film version of Journey’s End (1930), fated to direct Universal’s most famous horror films and doomed to die in his swimming pool in 1957. Anyway, he sweeps into the office of general manager Carl Laemmle Junior, who declares Whale a genius, yanks Frankenstein away from young Florey and presents it to Whale instead. Whale goes on to glory, removing Florey’s writing credit from Frankenstein, while Florey is offered Murders In The Rue Morgue (1932) as an inferior consolation prize. This historical cinema scandal is usually told with a twist: It was widely believed that Whale”s Frankenstein was superior to anything Florey might have delivered.

Hollywood history is always a target for revisionists, and there has been a growing revision of the James Whale myth since the release of Gods And Monsters (1998) starring Ian McKellen as the aged auteur. Author Brian Taves spearheaded this attack in his book The French Expressionist (published 1987), stating that “Florey’s knowledge, love and emulation of German Expressionism would have served Frankenstein better than Whale’s influences.” Perhaps those influences – not just the obvious ones – should be reviewed again before cinema history writes a new ending to this popular chapter. In his introduction to the Film Classics Library edition of Frankenstein (published 1974), author Richard Anobile wrote that the movie was a classic in spite of James Whale. Unwittingly, Anobile made something of a fool of himself, deprecating Whale for filmic deficiencies, arguing that Florey would have made a superior film and lamented the poor treatment Florey received, noting how Florey’s own writing credit had been removed and, when Florey protested, was restored only on foreign prints.

Hollywood history is always a target for revisionists, and there has been a growing revision of the James Whale myth since the release of Gods And Monsters (1998) starring Ian McKellen as the aged auteur. Author Brian Taves spearheaded this attack in his book The French Expressionist (published 1987), stating that “Florey’s knowledge, love and emulation of German Expressionism would have served Frankenstein better than Whale’s influences.” Perhaps those influences – not just the obvious ones – should be reviewed again before cinema history writes a new ending to this popular chapter. In his introduction to the Film Classics Library edition of Frankenstein (published 1974), author Richard Anobile wrote that the movie was a classic in spite of James Whale. Unwittingly, Anobile made something of a fool of himself, deprecating Whale for filmic deficiencies, arguing that Florey would have made a superior film and lamented the poor treatment Florey received, noting how Florey’s own writing credit had been removed and, when Florey protested, was restored only on foreign prints.

Robert Florey, a very gifted filmmaker and screenwriter, passed away in 1979. He wasn’t always lucky – Chaplin wanted to delete Florey’s contributions to Monsieur Verdoux (1947) – and his work is ripe for re-examination. During the eighties his original shooting script for Frankenstein was circulated amongst collectors, as used in the famous two-reel test and revamped after Whale took control. Indeed, the script contains most of the film’s famous scenes, filled with camera angles, sound effects and Florey’s annotation. It’s impressive work, and might cause a skeptic to question Whale’s contribution to Frankenstein. In fact the script, co-written by Garrett Fort, contained several surprises.

Robert Florey, a very gifted filmmaker and screenwriter, passed away in 1979. He wasn’t always lucky – Chaplin wanted to delete Florey’s contributions to Monsieur Verdoux (1947) – and his work is ripe for re-examination. During the eighties his original shooting script for Frankenstein was circulated amongst collectors, as used in the famous two-reel test and revamped after Whale took control. Indeed, the script contains most of the film’s famous scenes, filled with camera angles, sound effects and Florey’s annotation. It’s impressive work, and might cause a skeptic to question Whale’s contribution to Frankenstein. In fact the script, co-written by Garrett Fort, contained several surprises.

For instance, there’s a wild scene with two peasants, Johann and Gretel, preparing to make love in their cottage while the Monster is peeping through the window. He watches as Johann teasingly plays with Gretel’s chemise then gets her into bed. “There is the sound of the bedspring squeaking. The mattress sags in towards the middle. We hear a smothered exclamation or two. A short triumphant laugh from Johann. Then the chemise is flung into the camera, draping itself rakishly over the foot of the bed.” The Monster breaks in, throws Johann into a corner and attacks Gretel, while their children tremble with fear in the next room. There’s another scene involving a puppet show in the village street during the wedding festivities with Punch-And-Judy-style marionettes. Florey noted, “Find other names – Punch And Judy’s show – on which G. Fort insisted is too British.”

For instance, there’s a wild scene with two peasants, Johann and Gretel, preparing to make love in their cottage while the Monster is peeping through the window. He watches as Johann teasingly plays with Gretel’s chemise then gets her into bed. “There is the sound of the bedspring squeaking. The mattress sags in towards the middle. We hear a smothered exclamation or two. A short triumphant laugh from Johann. Then the chemise is flung into the camera, draping itself rakishly over the foot of the bed.” The Monster breaks in, throws Johann into a corner and attacks Gretel, while their children tremble with fear in the next room. There’s another scene involving a puppet show in the village street during the wedding festivities with Punch-And-Judy-style marionettes. Florey noted, “Find other names – Punch And Judy’s show – on which G. Fort insisted is too British.”

There is also an epilogue in the village church, in which Baron Frankenstein and Victor meet the praying Elizabeth. “The last thing we see is Victor and Elizabeth standing by the pillar and the morning sun breaking over them, while in b.g. kneeling before the shadowy altar, the broken figure of the old Baron. Camera moves back at increased tempo to the very doors of the church, which close slowly.” On the 16th and 17th of June 1931, Florey shot his two-reel test featuring the scene between Doctor Waldman and Victor, and the creation scene with Lugosi as the monster. Soon after, James Whale was given Frankenstein. Few would argue that Florey was abused by Universal. However, as for the argument as to who would have made a better film, it’s important to analyse the script as well as the finished film.

There is also an epilogue in the village church, in which Baron Frankenstein and Victor meet the praying Elizabeth. “The last thing we see is Victor and Elizabeth standing by the pillar and the morning sun breaking over them, while in b.g. kneeling before the shadowy altar, the broken figure of the old Baron. Camera moves back at increased tempo to the very doors of the church, which close slowly.” On the 16th and 17th of June 1931, Florey shot his two-reel test featuring the scene between Doctor Waldman and Victor, and the creation scene with Lugosi as the monster. Soon after, James Whale was given Frankenstein. Few would argue that Florey was abused by Universal. However, as for the argument as to who would have made a better film, it’s important to analyse the script as well as the finished film.

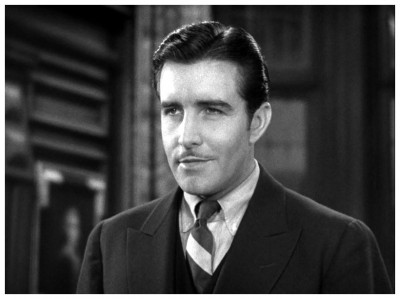

There are profound differences. The character of Frankenstein has very little personality in Florey’s script, particularly in relation to his Monster. The first time we see creator and creation after the laboratory scene, the Monster is chained in the cellar with Frankenstein torturing it with a whip and hot poker. “Hah, there! You’re beginning to understand my language, eh? Obey me!” It was James Whale who transformed Frankenstein from this smug bullying mad doctor into a poetic dreamer. After Whale took over, the famous Frankenstein soliloquy was added, beautifully delivered by Colin Clive: “Have you never wanted to look beyond the clouds and the stars, or to know what causes the trees to bud? And what changes darkness into light? If I could discover just one of these things – what eternity is, for example – I wouldn’t care if they did think I was crazy!”

There are profound differences. The character of Frankenstein has very little personality in Florey’s script, particularly in relation to his Monster. The first time we see creator and creation after the laboratory scene, the Monster is chained in the cellar with Frankenstein torturing it with a whip and hot poker. “Hah, there! You’re beginning to understand my language, eh? Obey me!” It was James Whale who transformed Frankenstein from this smug bullying mad doctor into a poetic dreamer. After Whale took over, the famous Frankenstein soliloquy was added, beautifully delivered by Colin Clive: “Have you never wanted to look beyond the clouds and the stars, or to know what causes the trees to bud? And what changes darkness into light? If I could discover just one of these things – what eternity is, for example – I wouldn’t care if they did think I was crazy!”

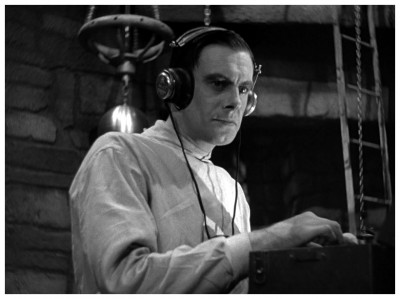

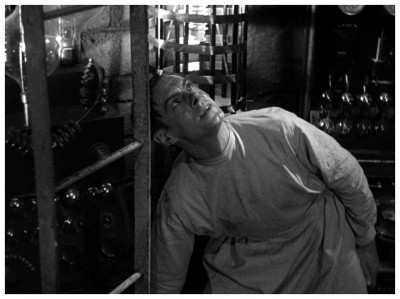

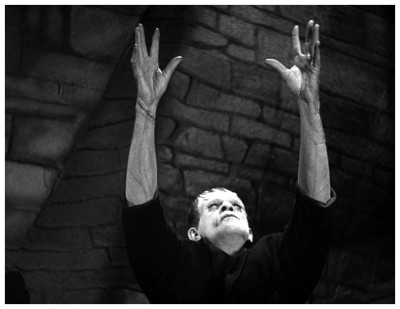

It was only after Whale took on the property that a scene was added of the doctor softly teaching the Monster in the laboratory, as well as the timeless scene of the Monster reaching for the rays of sunlight – perhaps the most profound vignette of the entire Frankenstein saga. Much of the power of Frankenstein stems from its perfect casting. Again, Whale was responsible. While Universal was considering Leslie Howard for the role of Frankenstein, Whale sent for his favourite leading actor. “I chose Colin Clive for Frankenstein because he had exactly the right kind of tenacity to go through with anything, together with the kind of romantic quality which makes strong men leave civilisation to shoot big game.” It was Whale too who selected Boris Karloff as the Monster after studying his face in the Universal canteen. Carl Laemmle Junior very much wanted to keep Bela Lugosi in the picture due to potential box-office (despite the actor’s egotistical protestations). Fortunately, Whale insisted on Karloff.

It was only after Whale took on the property that a scene was added of the doctor softly teaching the Monster in the laboratory, as well as the timeless scene of the Monster reaching for the rays of sunlight – perhaps the most profound vignette of the entire Frankenstein saga. Much of the power of Frankenstein stems from its perfect casting. Again, Whale was responsible. While Universal was considering Leslie Howard for the role of Frankenstein, Whale sent for his favourite leading actor. “I chose Colin Clive for Frankenstein because he had exactly the right kind of tenacity to go through with anything, together with the kind of romantic quality which makes strong men leave civilisation to shoot big game.” It was Whale too who selected Boris Karloff as the Monster after studying his face in the Universal canteen. Carl Laemmle Junior very much wanted to keep Bela Lugosi in the picture due to potential box-office (despite the actor’s egotistical protestations). Fortunately, Whale insisted on Karloff.

It should also be noted that, once Mae Clarke was cast, Whale had her part expanded and made the role of Elizabeth more vivid. Whale had her visit Doctor Waldman along with Victor, which added to the drama, and had her present at the Monster’s creation. A woman forced to witness her fiancee’s creation of a man is typical of Whale, full of all kinds of quirky dramatic significance. Whale’s other touches include his wonderfully theatrical (yet effectively cinematic) classic introduction to the Monster, moments of black comedy and just a dash of sadism. However, his major contribution to the project was sympathy – a sympathy for the dynamic poetic Frankenstein and for his lost bewildered Monster. For all the wizardry of Jack Pierce‘s makeup, the electrical pyrotechnics of Kenneth Strickfaden, the talent of the supporting cast, and the spadework of Florey’s script, Frankenstein retains its power because of this Whale-directed sympathy for both Creator and Monster, ultimately made magic by Clive and, supremely, by Karloff.

It should also be noted that, once Mae Clarke was cast, Whale had her part expanded and made the role of Elizabeth more vivid. Whale had her visit Doctor Waldman along with Victor, which added to the drama, and had her present at the Monster’s creation. A woman forced to witness her fiancee’s creation of a man is typical of Whale, full of all kinds of quirky dramatic significance. Whale’s other touches include his wonderfully theatrical (yet effectively cinematic) classic introduction to the Monster, moments of black comedy and just a dash of sadism. However, his major contribution to the project was sympathy – a sympathy for the dynamic poetic Frankenstein and for his lost bewildered Monster. For all the wizardry of Jack Pierce‘s makeup, the electrical pyrotechnics of Kenneth Strickfaden, the talent of the supporting cast, and the spadework of Florey’s script, Frankenstein retains its power because of this Whale-directed sympathy for both Creator and Monster, ultimately made magic by Clive and, supremely, by Karloff.

Whale’s insight was not lost on Boris Karloff who, in one of his last interviews, gave his own feelings on the controversy: “Nowadays everyone sees my Monster in Frankenstein as being a rather touching sort of hulk. Well that, you know, was quite unusual in the thirties and I don’t think the main screenwriter, Bob Florey, really intended there to be much pathos inside the character. But Whale and I thought there should be – we didn’t want the kind of rampaging monstrosity that Universal seemed to think we should go in for. We had to have some pathos otherwise our audiences just wouldn’t think about the film after they’d left the theatre, and Whale very much wanted them to do that. He wanted to make some impact on them, and so did I.”

Whale’s insight was not lost on Boris Karloff who, in one of his last interviews, gave his own feelings on the controversy: “Nowadays everyone sees my Monster in Frankenstein as being a rather touching sort of hulk. Well that, you know, was quite unusual in the thirties and I don’t think the main screenwriter, Bob Florey, really intended there to be much pathos inside the character. But Whale and I thought there should be – we didn’t want the kind of rampaging monstrosity that Universal seemed to think we should go in for. We had to have some pathos otherwise our audiences just wouldn’t think about the film after they’d left the theatre, and Whale very much wanted them to do that. He wanted to make some impact on them, and so did I.”

All the Universal movie monsters – Dracula (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), The Wolf Man (1941), The Phantom Of The Opera (1943), Creature From The Black Lagoon (1953) – share a strange, almost spiritual aura of alienation, loneliness and bitterness, making them all kin to Frankenstein’s hapless Monster. This is the true legacy of Universal’s horror tales. It’s with this thought in mind I’ll bid you a good night, but not before thanking the April 1987 issue of American Cinematographer magazine for assisting my research for this article. I look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to put goose-bumps on your goose-bumps with more ambient atmosphere so thick and chumpy you could carve it with a chainsaw, in yet another pants-filling fright-night for…Horror News! Toodles!

All the Universal movie monsters – Dracula (1931), The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), The Wolf Man (1941), The Phantom Of The Opera (1943), Creature From The Black Lagoon (1953) – share a strange, almost spiritual aura of alienation, loneliness and bitterness, making them all kin to Frankenstein’s hapless Monster. This is the true legacy of Universal’s horror tales. It’s with this thought in mind I’ll bid you a good night, but not before thanking the April 1987 issue of American Cinematographer magazine for assisting my research for this article. I look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to put goose-bumps on your goose-bumps with more ambient atmosphere so thick and chumpy you could carve it with a chainsaw, in yet another pants-filling fright-night for…Horror News! Toodles!

Frankenstein (1931) is now available on Blu ray per Universal Studios on the

“Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection”

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Frankenstein. He is the very definition of the word Monster. This movie is the reason why most of us our horror fans. It’s been re-imaged countless times, but non of the other movies holds a candle of the 1931 version of Frankenstein.