SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“After their latest rocket fails, Doctor Charles Cargraves and retired General Thayer have to start over again. This time, General Thayer approaches Jim Barnes, the head of his own aviation construction firms to help build a rocket that will take them to the moon. Together they gather the captains of industry and all pledge to support the goals of having the united States be the first to put a man on the moon. They build their rocket and successfully leave the Earth’s gravitational pull and make the landing as scheduled. Barnes has miscalculated their fuel consumption however and after stripping the ship bare, they are still a hundred pounds too heavy meaning that one of them will have to stay behind.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Movies concerning space travel weren’t very successful in the early fifties, despite the fact that the science fiction trend of the decade was sparked by two such productions: Destination Moon (1950) and Rocketship XM (1950). Destination Moon was first to go into production but Rocketship XM, made faster and cheaper, reached the cinema first. Destination Moon didn’t reflect the darker fears given form in subsequent science fiction films. It was basically a pseudo-documentary about a journey to the moon, though the reason for the trip is to prevent ‘unfriendly foreign power’ from getting there first and turning the moon into a military base. Although it was based on a juvenile novel by Robert Heinlein called Rocketship Galileo written in 1947, it had very little to do with the original story, which concerned three boys and their scientist uncle who construct a rocketship virtually in their backyard and travel to the moon where they discover a Nazi moon-base.

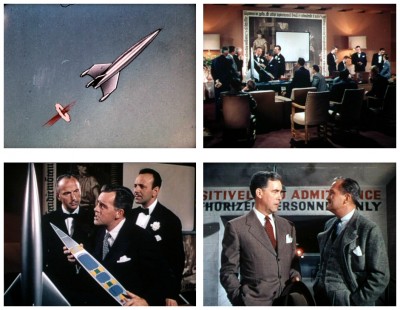

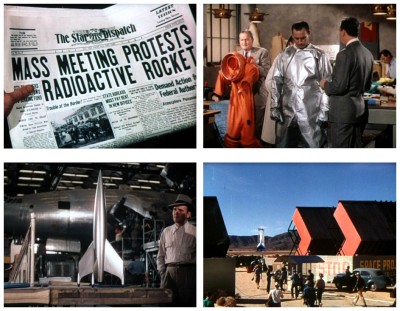

The film begins with inventor Doctor Cargraves (Warner Anderson) and General Thayer (Tom Powers) watching as their experimental rocket crashes after take-off. The army orders a stop to the work but they then discover that enemy saboteurs were responsible for the crash and they decide to continue. As the government refuses to supply them with further funds they approach a rich industrialist named Jim Barnes (John Archer) to ask for his help. He agrees, saying “The government always turns to private enterprise when they’re in a jam.” The huge spaceship is built in the Mojave desert but, as ‘unfriendly foreign powers’ have somehow succeeded in manipulating public opinion against the project, the government bans the take-off. However, despite the protests of the local sheriff, the pioneers take-off anyway and are accompanied by radio technician Joe Sweeney (Dick Wesson), whose prime function during the mission is to provide comic relief, an assignment in which he fails miserably.

The film begins with inventor Doctor Cargraves (Warner Anderson) and General Thayer (Tom Powers) watching as their experimental rocket crashes after take-off. The army orders a stop to the work but they then discover that enemy saboteurs were responsible for the crash and they decide to continue. As the government refuses to supply them with further funds they approach a rich industrialist named Jim Barnes (John Archer) to ask for his help. He agrees, saying “The government always turns to private enterprise when they’re in a jam.” The huge spaceship is built in the Mojave desert but, as ‘unfriendly foreign powers’ have somehow succeeded in manipulating public opinion against the project, the government bans the take-off. However, despite the protests of the local sheriff, the pioneers take-off anyway and are accompanied by radio technician Joe Sweeney (Dick Wesson), whose prime function during the mission is to provide comic relief, an assignment in which he fails miserably.

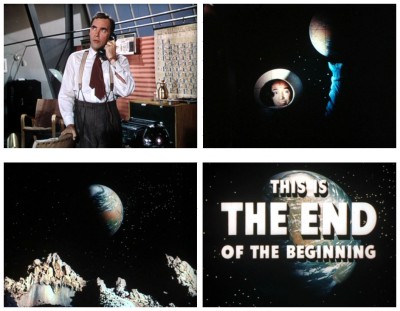

The most dramatic event on the trip to the moon occurs when Cargraves, who goes outside to repair a damaged radar antenna, lose his magnetised footing and drifts off into space. He’s rescued by General Thayer, who uses a spare air tank as a miniature rocket. They eventually land safely on the moon, at which point Cargraves announces, “By the grace of God and in the name of the USA I take possession of this planet for the benefits of mankind.” Fortunately, Neil Armstrong, nineteen years later, had a better scriptwriter. When the time comes to take-off, the group discover that they have only enough fuel to bring three people back to Earth and, for a while, it looks as if one of them must remain behind but, by stripping the ship of everything except the bare essentials, they all return safely.

The most dramatic event on the trip to the moon occurs when Cargraves, who goes outside to repair a damaged radar antenna, lose his magnetised footing and drifts off into space. He’s rescued by General Thayer, who uses a spare air tank as a miniature rocket. They eventually land safely on the moon, at which point Cargraves announces, “By the grace of God and in the name of the USA I take possession of this planet for the benefits of mankind.” Fortunately, Neil Armstrong, nineteen years later, had a better scriptwriter. When the time comes to take-off, the group discover that they have only enough fuel to bring three people back to Earth and, for a while, it looks as if one of them must remain behind but, by stripping the ship of everything except the bare essentials, they all return safely.

Unlike most science fiction films of the fifties, Destination Moon is scientifically accurate given the date it was made. German rocket expert Hermann Oberth – who worked on Fritz Lang’s Woman In The Moon (1929) – and Robert Heinlein were enlisted as technical advisors on the film, and great care was taken with all the scientific details, including the recreation of the lunar landscape designed by space artist Chesley Bonestell. Bonestell, who knew full well there was no water on the moon and probably never was, was forced by producer George Pal to include cracks on the moon’s surface in order to create a sense of perspective on the set. Unfortunately, other Hollywood producers quickly realised that it didn’t matter whether their movies were scientifically accurate or not, since the number of people who knew or even cared was relatively small. Film critics were among those who didn’t consider such things terribly important. The London Daily Mail critic wrote in his review of the film, “The temptation to populate the moon with pretty girls has been resisted. As a boy’s magazine thriller it is fine. And a scientific man assured me that the scientific banter is not too foolish – if you’re interested.”

Unlike most science fiction films of the fifties, Destination Moon is scientifically accurate given the date it was made. German rocket expert Hermann Oberth – who worked on Fritz Lang’s Woman In The Moon (1929) – and Robert Heinlein were enlisted as technical advisors on the film, and great care was taken with all the scientific details, including the recreation of the lunar landscape designed by space artist Chesley Bonestell. Bonestell, who knew full well there was no water on the moon and probably never was, was forced by producer George Pal to include cracks on the moon’s surface in order to create a sense of perspective on the set. Unfortunately, other Hollywood producers quickly realised that it didn’t matter whether their movies were scientifically accurate or not, since the number of people who knew or even cared was relatively small. Film critics were among those who didn’t consider such things terribly important. The London Daily Mail critic wrote in his review of the film, “The temptation to populate the moon with pretty girls has been resisted. As a boy’s magazine thriller it is fine. And a scientific man assured me that the scientific banter is not too foolish – if you’re interested.”

Some critics had absolutely no idea what they were talking about, for instance, in an article on the film published in The Spectator, Peter King wrote, “It is said that a rocketship to the moon would be similar to a V2 rocket, but the fuel in these allows only a slow escape of exhaust gases and, consequently, a slow forward speed. The German V2 had nearly 60,000 pounds of thrust or about ten times the power of a jet engine. It reached the height of sixty miles at a top speed of something like 3,600 miles per hour. But a rocket to make some impression on stellar distances would need to travel about ten times as fast or somewhere near the velocity of light. No known fuel is capable of firing off a rocket at these speeds. Work is being done on chemical, chiefly liquid, propellants and, less hopefully, on atom power. But science fiction, which is the pretentious successor to the imaginative stories of Wells and Verne, has its own solutions. One of the most attractive is the ‘hyper-drive’ which cuts swiftly through the fourth dimension of ‘hyper-space’ and makes the comic strips fascinating reading.” But not as fascinating as Mr. King’s own writing, which is a perfect example of ‘hyper-journalism’ that cuts swiftly through the logic barrier and goes where no man has gone before. For years now ‘sophisticated’ journalists writing for prestigious publications have picked on science fiction from time-to-time as a way to get easy laughs but, invariably, they end up making fools of themselves. Even the lowliest sci-fi hack would have known that ten times 3,600 mph is somewhat less than the speed of light, and they would not have confused interplanetary distances with interstellar ones. They might even have included a mention of something called ‘escape velocity’.

Some critics had absolutely no idea what they were talking about, for instance, in an article on the film published in The Spectator, Peter King wrote, “It is said that a rocketship to the moon would be similar to a V2 rocket, but the fuel in these allows only a slow escape of exhaust gases and, consequently, a slow forward speed. The German V2 had nearly 60,000 pounds of thrust or about ten times the power of a jet engine. It reached the height of sixty miles at a top speed of something like 3,600 miles per hour. But a rocket to make some impression on stellar distances would need to travel about ten times as fast or somewhere near the velocity of light. No known fuel is capable of firing off a rocket at these speeds. Work is being done on chemical, chiefly liquid, propellants and, less hopefully, on atom power. But science fiction, which is the pretentious successor to the imaginative stories of Wells and Verne, has its own solutions. One of the most attractive is the ‘hyper-drive’ which cuts swiftly through the fourth dimension of ‘hyper-space’ and makes the comic strips fascinating reading.” But not as fascinating as Mr. King’s own writing, which is a perfect example of ‘hyper-journalism’ that cuts swiftly through the logic barrier and goes where no man has gone before. For years now ‘sophisticated’ journalists writing for prestigious publications have picked on science fiction from time-to-time as a way to get easy laughs but, invariably, they end up making fools of themselves. Even the lowliest sci-fi hack would have known that ten times 3,600 mph is somewhat less than the speed of light, and they would not have confused interplanetary distances with interstellar ones. They might even have included a mention of something called ‘escape velocity’.

Destination Moon, produced by George Pal (a former animation expert from Hungary) and directed by Irving Pichel (an ex-actor), was rather unique among fifties science fiction films in having an actual science fiction author work on the screenplay. Together with writers Rip Von Ronkel and James O’Hanlon, Robert Heinlein himself was employed to work on the script, and it was thanks to him that the more sensational elements were kept out of the proceedings. He later told me, “For a time, we had a version of the script which included dude ranches, cowboys, guitars and hillbilly songs on the moon, combined with pseudo-scientific gimmicks that would have puzzled even Flash Gordon.” Perhaps, though, this version might have been a little more entertaining than the film that actually reached the screen because, unfortunately, Destination Moon turned out to be incredibly dull despite its scientific authenticity.

Destination Moon, produced by George Pal (a former animation expert from Hungary) and directed by Irving Pichel (an ex-actor), was rather unique among fifties science fiction films in having an actual science fiction author work on the screenplay. Together with writers Rip Von Ronkel and James O’Hanlon, Robert Heinlein himself was employed to work on the script, and it was thanks to him that the more sensational elements were kept out of the proceedings. He later told me, “For a time, we had a version of the script which included dude ranches, cowboys, guitars and hillbilly songs on the moon, combined with pseudo-scientific gimmicks that would have puzzled even Flash Gordon.” Perhaps, though, this version might have been a little more entertaining than the film that actually reached the screen because, unfortunately, Destination Moon turned out to be incredibly dull despite its scientific authenticity.

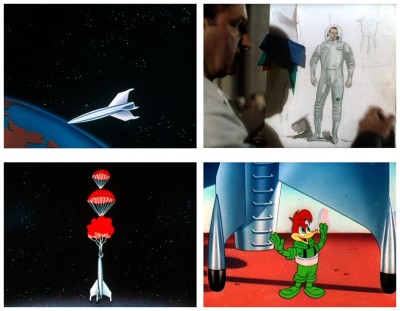

Nevertheless it did well at the box-office. Pal’s friend Walter Lantz contributed a Woody Woodpecker cartoon explaining the intricacies of space travel, the music by Leith Stevens (later of The Outer Limits) is suitably grand and the excellent special effects, supervised by Lee Zavitz and George Pal, won an Oscar that year. One of Heinlein’s abilities as an author was to make space travel grittily real – he could make his readers feel what it might be like to live and work on a spaceship. He was able to achieve this on the printed page, but to recreate it on-screen demanded resources far beyond those available to filmmakers in the fifties. It wasn’t until many years later that Arthur C. Clarke, who concentrated on themes similar to Heinlein’s was to see his work given cinematic flesh by the genius of Stanley Kubrick, but Kubrick’s equivalent didn’t exist in the early fifties. But that’s another story for another time. Right now I’d like to profusely thank Astounding Science Fiction magazine (July 1950) for assisting my research for this article, and ask you to please join me next week when I burst your blood vessels with more terror-filled excursions to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Nevertheless it did well at the box-office. Pal’s friend Walter Lantz contributed a Woody Woodpecker cartoon explaining the intricacies of space travel, the music by Leith Stevens (later of The Outer Limits) is suitably grand and the excellent special effects, supervised by Lee Zavitz and George Pal, won an Oscar that year. One of Heinlein’s abilities as an author was to make space travel grittily real – he could make his readers feel what it might be like to live and work on a spaceship. He was able to achieve this on the printed page, but to recreate it on-screen demanded resources far beyond those available to filmmakers in the fifties. It wasn’t until many years later that Arthur C. Clarke, who concentrated on themes similar to Heinlein’s was to see his work given cinematic flesh by the genius of Stanley Kubrick, but Kubrick’s equivalent didn’t exist in the early fifties. But that’s another story for another time. Right now I’d like to profusely thank Astounding Science Fiction magazine (July 1950) for assisting my research for this article, and ask you to please join me next week when I burst your blood vessels with more terror-filled excursions to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews