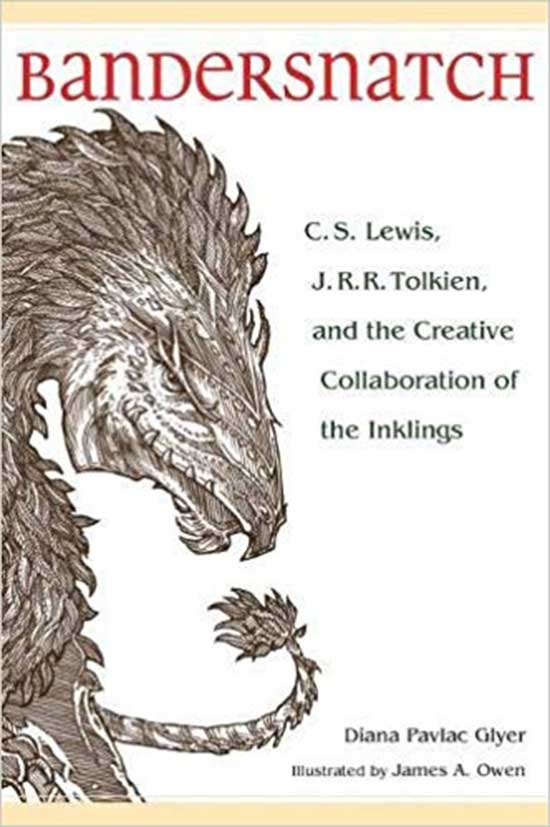

“Bandersnatch” appeared on my radar non-traditionally. Frankly, I was disinterested in the trailers and promotional bumps that autoplayed when I turned on Netflix. It wasn’t until all the memes started flooding social media that I knew I had to check it out.

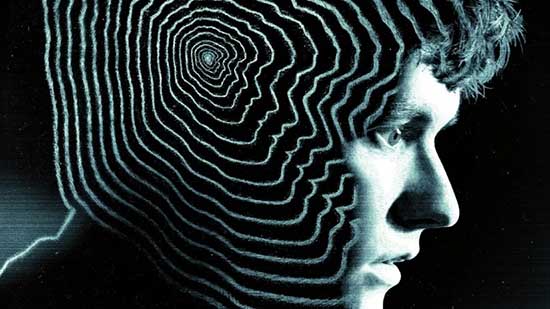

“Bandersnatch” is the story of Stefan, a twenty something only child in the 1980s who sets out to turn a choose your own adventure novel, also called Bandersnatch, into a video game. From there, the story possibilities diverge. Depending on the user choices, one can uncover the details of his mother’s death, explore trippy philosophy, drive him to suicide, kill his father, or instigate a Kill-Bill type fight with his therapist.

Because of its nontraditional approach to storytelling, “Bandersnatch’s” role in the science fiction horror genre is hard to peg. Each iteration of the story is different, and certain decisions end the story before the horror has time to unfold. Taken as a whole, however, Bandersnatch occupies a unique place in the scifi horror genre that is bound to be emulated.

In Danse Macabre, Stephen King states that horror exists on three levels: revulsion (gut), terror (existential), and fear (psychological). Revulsion is an instinctive response to gross beit physical (the sound of a body crunching on asphalt after a balcony freefall) or moral (why not chop up daddy?). Of course “Bandersnatch” is filled with moments of revulsion, but it is not a SAW type horror. Indeed, considering the brutality of some contemporary horror (or the nightly news for that matter), most of these revolting moments come across as tame if not outright mundane.

Terror is an existential response to disturbing concepts. Terror is why you think about a horror movie long after the lights come back on. Terror has always been the bread and butter of Black Mirror, and arguably the scifi horror genre as a whole. These “what if?” questions follow us long after the images of gore and debauchery have faded. What if we could digitally replicate consciousness? What if we could erase a criminals memory of their wrongdoings or a soldier’s memory of humanity? Despite Black Mirror’s traditional success in instigating terror, “Bandersnatch’s” biggest pitfall is its “what if” questions. What if we could control someone else in the past? Time manipulation like that feels hokey, like a long forgotten episode of Star Trek. What if the illusion of choice could drive us mad? Girl it already does. Pop a xanax and climb aboard, the Bipolar Express leaves in one hour.

“Bandersnatch” communicates most effectively and clearly through fear. Fear is the psychological response to danger. It’s why we scream at spiders. It’s why they always kill the dog. It’s why no matter how much you prepare yourself, you’re probably going to still squeal at the jump scares. However, unlike the standard horror rolodex of monsters, killers, and soundtrack manipulation, “Bandersnatch” attacks the audience’s psyche in a different way. And that is repetitive culpability. This new media risk of “choose your own adventure” television could not have found a better genre than horror.

One of the more innovative elements of this new style of horror media is its ability to be revisited through replay. Another Netflix hit, The Haunting of Hill House utilized a bevy of periphery ghosts to invite its users to watch the series again and again. However, we can build up an immunity, or at least a tolerance, to fear. Repeat viewings lose their edge; we know what is coming. “Bandersnatch” circumvents this with an ever changing storyline based on user choice. With over five hours of scenes available, we are guaranteed to catch something new each time. While the freshness helps to maintain fear and anxiety levels, even repeat scenes tend to reveal something new upon a second viewing. Not-so-subtle foreshadowing like Collin’s game may remind the viewer of previous choices, and some characters return to the screen with uncanny knowledge of previous iterations. As a result, the viewer, characters, and plot become so tightly intertwined that it becomes impossible to escape a subtle fear rarely utilized in horror: culpability.

Culpability, or a feeling of guilt and responsibility, can heighten audience anxiety which in turn heightens other elements of fear, terror, and revulsion. One work that successfully manipulated feelings of culpability is the 2008 American remake Funny Games and the original German film. Funny Games follows two sociopaths as they manipulate the social conventions of a wealthy family to torture and ultimately kill them. The killers, Peter and Paul, acknowledge their work’s “value [as] entertainment.” Indeed, what begins as subtle winks and nods towards the fourth wall becomes an open invitation to the audience. We are asked to pick sides, make bets.

Culpability, or a feeling of guilt and responsibility, can heighten audience anxiety which in turn heightens other elements of fear, terror, and revulsion. One work that successfully manipulated feelings of culpability is the 2008 American remake Funny Games and the original German film. Funny Games follows two sociopaths as they manipulate the social conventions of a wealthy family to torture and ultimately kill them. The killers, Peter and Paul, acknowledge their work’s “value [as] entertainment.” Indeed, what begins as subtle winks and nods towards the fourth wall becomes an open invitation to the audience. We are asked to pick sides, make bets.

Peter eventually calls out the viewer directly, “Do you think it’s enough? I mean, you want a real ending, don’t you?” In Funny Games, however, the fear came from the helplessness of your culpability. You can turn off the movie right now, save the family, do the right thing. But the truth is, we do want a real ending. And “Bandersnatch” gives us dozens, some more real than others, all under our control. Instead of helplessness becoming the driving anxiety behind our culpability, it is the overabundance of choice that pushes fear. Not only are we called out as bystanders, we become the perpetrators ourselves. Perhaps there is a bit of Peter in all of us when we play “Bandersnatch”, when we value entertainment over life in our choices.

Even the method of choice introduces new elements of fear. When a decision is approaching, the controller will rumble. Then, the options appear beneath a timer that immediately begins to count down. A necessary element to choosing your own adventure has itself been transformed into a means to scare. Often considered a “cheap shot” by audiences, the jump scare has been a mainstay of the horror genre since its inception in 1896 with Le Manoir du Diable’s creative cuts that made monsters appear and disappear in an instant. “Bandersnatch” has created a new jump scare with the help of the rumble mode on most video game controllers. The need to make decisions forces the viewer into a tactile engagement previously unutilized for private home viewing. Like the rapid changes of the jump-scare, the buzz of the controller shocks the viewer to attention. The timer acts in much the same way as Jaws’ score to keep us waiting for the repercussions of our choices.

Unfortunately, however, the anxiety of culpability rarely pays off regardless of the choices made. “Bandersnatch” fails to trigger enough instinctive fears, especially compared to previous Black Mirror successes like “Playtest” and “White Bear.” Combined with its weak questions of terror and only passible moments of revulsion, “Bandersnatch: ultimately falls short of its potential.

Although, “Bandersnatch” may not be the greatest work in the choose your own adventure film genre, it has this author hoping that it is the next big thing.

Who would you like to see make a choose your own adventure horror?

Article by Karley Stasko

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews