SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“The president of Civic TV Channel 83, Max Renn, is always looking for new cheap and erotic movies for his station. When his employee, Harlan, decodes a pirate video broadcast showing torture, murder, and mutilation called Videodrome, Max becomes obsessed to get this series for his channel. He contacts his supplier, Masha, and asks her to find the party responsible for the transmission. A couple of days later, Masha tells that Videodrome is real snuff movies. Max’s sado-masochistic girlfriend Nicki Brand decides to travel to Pittsburgh, where the show is based, to audition. Max investigates further, and through a video by the media prophet Brian O’Blivion, he learns that that TV screens are the retina of the mind’s eye, being part of the brain, and Videodrome transmissions create a brain tumor in the viewer, changing the reality through video hallucination.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg, who has been dubbed by some as ‘The King Of Venereal Horror’, seemed to have been aiming for the title from the beginning of his career. It was, however, his first professional feature Shivers (1975), also known as They Came From Within and The Parasite Murders, that really earned him that particular moniker. His second feature, Rabid (1977), is structurally too close to Shivers to represent anything very interesting. The Brood (1979) is a far more startling exercise, not that Rabid was conventional by any standards other than Cronenberg’s. In Scanners (1981), horrific opening and closing sequences frame a grotesque story that is actually more science fiction than horror, and suggests that Cronenberg’s satirical interests go well beyond the venereal.

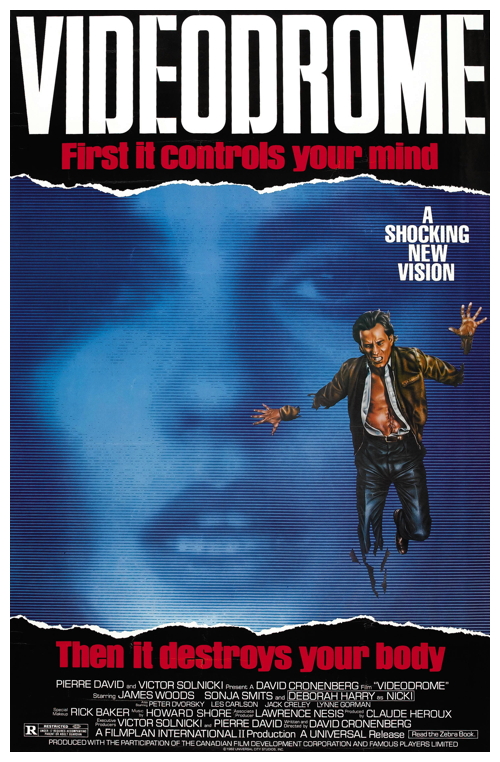

Cronenberg finally found the perfect metaphor for all his complex obsessions in Videodrome (1983). His most ambitious and expensive film up to that time, it was supposedly aimed at a much wider audience than the smallish band of cult followers he had so far collected. It bombed at the box-office badly, as it was almost bound to. The intellectual intricacy of the film was hardly going to endear him to a juvenile audience largely raised on traditional horror cliches, especially as Videodrome is a full-blooded attack on precisely those sadistic elements in horror films that some audience members were attracted to in the first place. It is a stroke of paradoxical daring to make a pulp exploitation movie which takes the dubious morality of pulp exploitation movies as its actual theme. It may seem like having your cake and eating it too, but Cronenberg pulls it off.

Cronenberg finally found the perfect metaphor for all his complex obsessions in Videodrome (1983). His most ambitious and expensive film up to that time, it was supposedly aimed at a much wider audience than the smallish band of cult followers he had so far collected. It bombed at the box-office badly, as it was almost bound to. The intellectual intricacy of the film was hardly going to endear him to a juvenile audience largely raised on traditional horror cliches, especially as Videodrome is a full-blooded attack on precisely those sadistic elements in horror films that some audience members were attracted to in the first place. It is a stroke of paradoxical daring to make a pulp exploitation movie which takes the dubious morality of pulp exploitation movies as its actual theme. It may seem like having your cake and eating it too, but Cronenberg pulls it off.

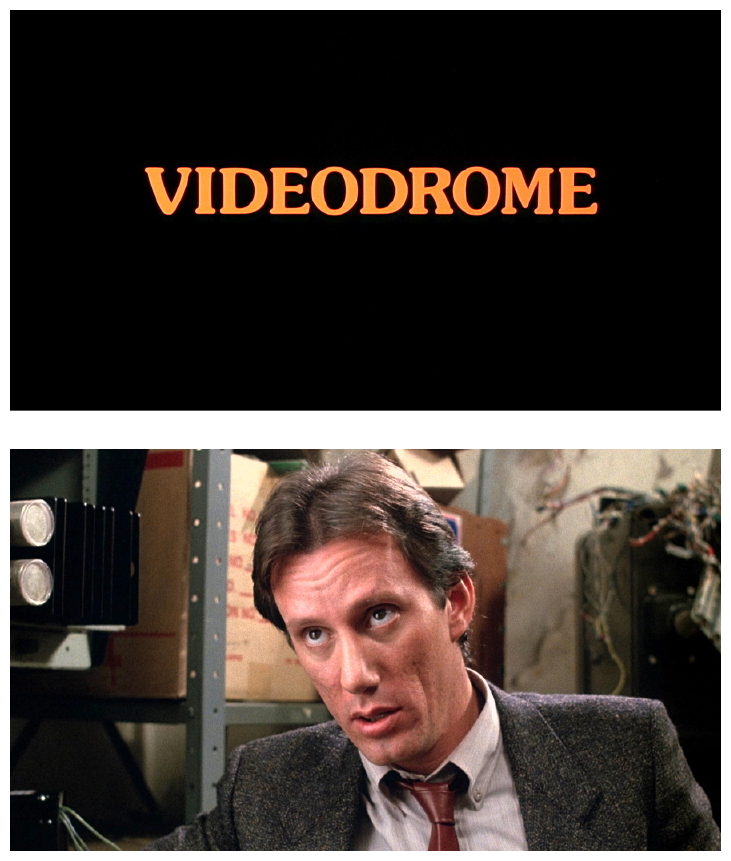

Max Renn (played with cold nervous conviction by James Woods) runs a tatty cable television station specialising in sex-and-violence programming. His sidekick Harlan (Peter Dvorsky), who pirates programmes from satellite broadcasts, discovers a strange channel called Videodrome that seems to show genuine scenes of sadism – a kind of snuff-movie channel – and Renn becomes obsessed with it. His baser feelings emerge, he slips into madness, his concepts of reality and illusion become blurred. But when he encounters sado-masochist behaviour in real life, via his new girlfriend Nicki Brand (played with serene perversity by pop star Deborah Harry), a television talk-show hostess, he is confused and disappointed. She, on the other hand, is excited (both sexually and intellectually) by the output of Videodrome, which seems to emanate from Pittsburgh, and she goes off in search of it.

Max Renn (played with cold nervous conviction by James Woods) runs a tatty cable television station specialising in sex-and-violence programming. His sidekick Harlan (Peter Dvorsky), who pirates programmes from satellite broadcasts, discovers a strange channel called Videodrome that seems to show genuine scenes of sadism – a kind of snuff-movie channel – and Renn becomes obsessed with it. His baser feelings emerge, he slips into madness, his concepts of reality and illusion become blurred. But when he encounters sado-masochist behaviour in real life, via his new girlfriend Nicki Brand (played with serene perversity by pop star Deborah Harry), a television talk-show hostess, he is confused and disappointed. She, on the other hand, is excited (both sexually and intellectually) by the output of Videodrome, which seems to emanate from Pittsburgh, and she goes off in search of it.

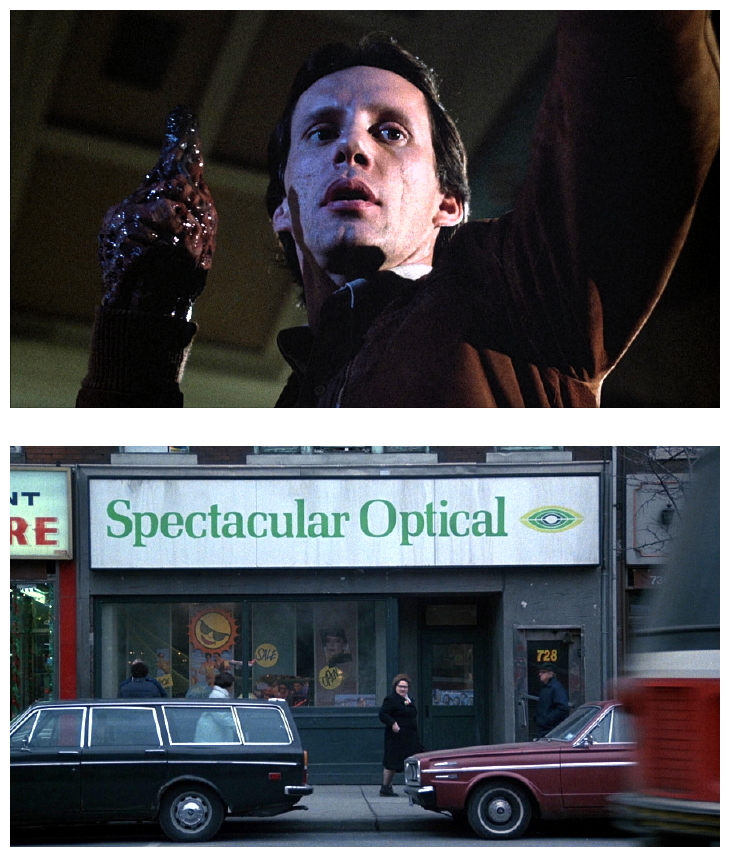

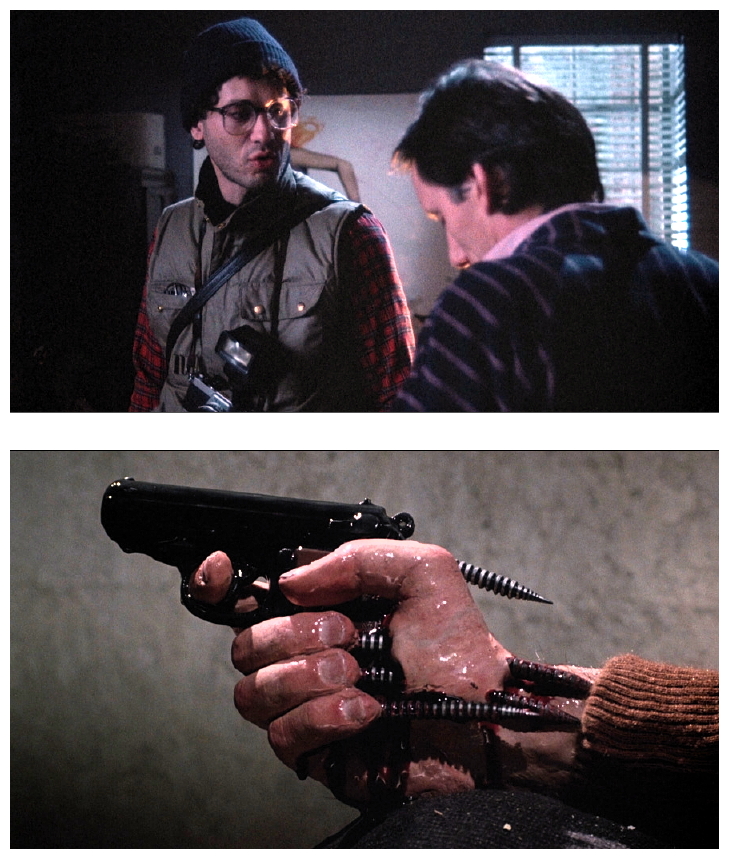

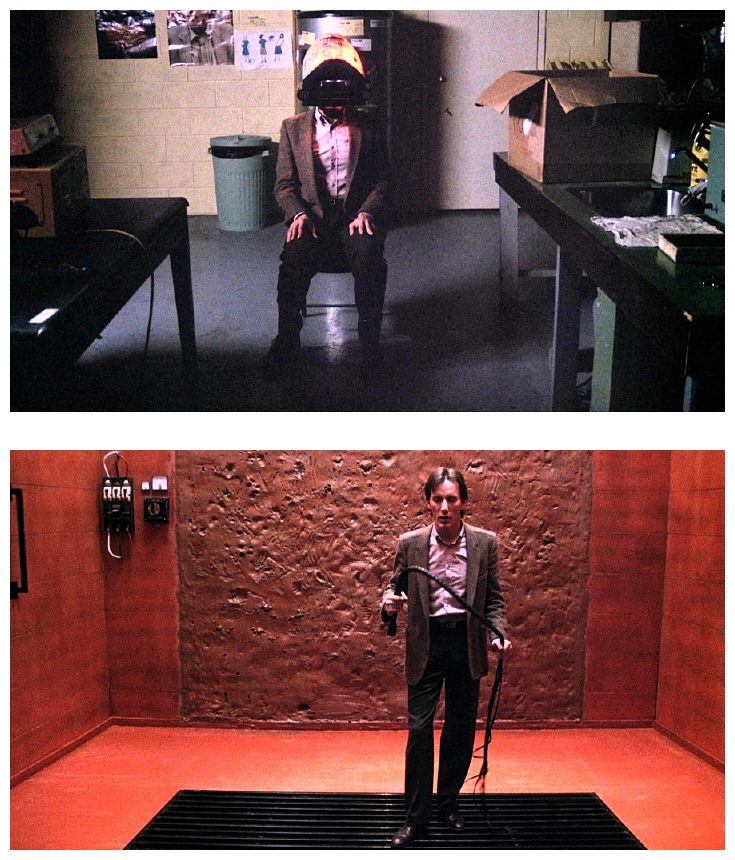

When we next see her she is a face and a body on the television screen. Events are too complex for proper synopsis, but the gist of the story is that Videodrome imagery literally changes the brains of its viewers, inducing a kind of cancer that results in powerful hallucinations. The second half of the film, in which Renn is surrounded by appealing plastic phenomena where objects become flesh, and flesh hardens into objects (at one point his hand literally becomes a ‘handgun’), may well be one long continuous hallucination. Certainly reality and Videodrome-induced fantasies are seamlessly joined. This is part of the point, of course, a trick played on the audience in order to make us think about the very real question of where media-reality stops and real-reality takes over. It turns out that puritanical right-wingers want Renn to broadcast Videodrome on his television station in order to destroy the minds of all people who would watch such trash.

When we next see her she is a face and a body on the television screen. Events are too complex for proper synopsis, but the gist of the story is that Videodrome imagery literally changes the brains of its viewers, inducing a kind of cancer that results in powerful hallucinations. The second half of the film, in which Renn is surrounded by appealing plastic phenomena where objects become flesh, and flesh hardens into objects (at one point his hand literally becomes a ‘handgun’), may well be one long continuous hallucination. Certainly reality and Videodrome-induced fantasies are seamlessly joined. This is part of the point, of course, a trick played on the audience in order to make us think about the very real question of where media-reality stops and real-reality takes over. It turns out that puritanical right-wingers want Renn to broadcast Videodrome on his television station in order to destroy the minds of all people who would watch such trash.

We are told that Videodrome was invented by a television guru with the unlikely name of Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley) who is actually dead but lives on in a vast library of recordings cared for by his daughter Bianca (Sonja Smits): “I am my father’s screen,” she pronounces with religious resonance like some sort of high priestess. As the plot becomes gradually more muddled and Renn gets more messed up, more clutter appears. In this rubble lies the film’s true meaning: Videodrome doesn’t control their viewers as much as simply bury them under tons of mindless garbage. It is not the violence in the media that drives Renn insane, but the fact that he cannot tear himself away from any broadcast. It becomes his drug. It doesn’t help either that the basis of Videodrome is Pittsburgh, the hometown of zombie filmmaker George Romero and pop-culture icon Andy Warhol, who declared Videodrome as “A Clockwork Orange (1971) for the eighties.”

We are told that Videodrome was invented by a television guru with the unlikely name of Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley) who is actually dead but lives on in a vast library of recordings cared for by his daughter Bianca (Sonja Smits): “I am my father’s screen,” she pronounces with religious resonance like some sort of high priestess. As the plot becomes gradually more muddled and Renn gets more messed up, more clutter appears. In this rubble lies the film’s true meaning: Videodrome doesn’t control their viewers as much as simply bury them under tons of mindless garbage. It is not the violence in the media that drives Renn insane, but the fact that he cannot tear himself away from any broadcast. It becomes his drug. It doesn’t help either that the basis of Videodrome is Pittsburgh, the hometown of zombie filmmaker George Romero and pop-culture icon Andy Warhol, who declared Videodrome as “A Clockwork Orange (1971) for the eighties.”

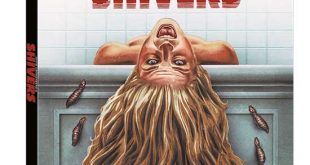

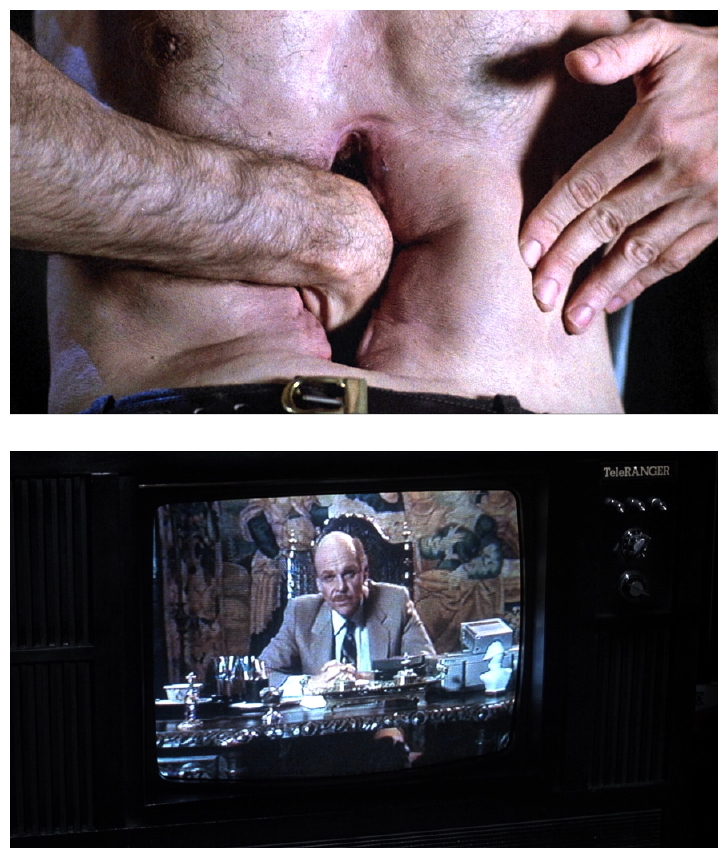

There is only one location that is ‘clean’ though not spotlessly shiny, and that’s the renaissance room of Videodrome’s main opponents, the O’Blivions, a sanctuary hidden away from a media-infected real world where they defiantly try to preserve art treasures from contamination. The most startling images concern Renn’s television, which softens and deforms to becomes flesh, and his stomach develops a vagina-like slit which, it turns out, can accept video cassettes. This sounds – and is – over the top, but one must admire a filmmaker who refuses to flinch from any metaphor, no matter how grotesque and how difficult it might be to incorporate into an ordinary narrative. With slimy special effects from award-winning monster-maker Rick Baker, it’s no wonder the film left audiences bemused.

There is only one location that is ‘clean’ though not spotlessly shiny, and that’s the renaissance room of Videodrome’s main opponents, the O’Blivions, a sanctuary hidden away from a media-infected real world where they defiantly try to preserve art treasures from contamination. The most startling images concern Renn’s television, which softens and deforms to becomes flesh, and his stomach develops a vagina-like slit which, it turns out, can accept video cassettes. This sounds – and is – over the top, but one must admire a filmmaker who refuses to flinch from any metaphor, no matter how grotesque and how difficult it might be to incorporate into an ordinary narrative. With slimy special effects from award-winning monster-maker Rick Baker, it’s no wonder the film left audiences bemused.

This is a deeply angry, deeply moral film. It tackles sophisticated questions in a genre context which is not, finally, flexible enough to deal with them all, but what a brave attempt! Do horror films corrupt? Can sadism be programmed? Is O’Blivion’s distinction between ‘hard media’ and ‘soft media’ valid or useful? Will television prove to be the ultimate aversion therapy? Does the religious phrase ‘the Word made Flesh’ have a new connotation in today’s world? There’s a lot of complex trans-substantiation imagery going on here. Videodrome is a prophetic film, a unique look into the future that has since become reality. The reason lies with its subject matter, the media – the fastest-developing branch of technology in the last few decades. We still essentially fly the same planes and drive the same cars, but our relation to media technology has changed dramatically. The basis of the story can almost be seen as a blueprint for contemporary fears over the effects of media violence.

This is a deeply angry, deeply moral film. It tackles sophisticated questions in a genre context which is not, finally, flexible enough to deal with them all, but what a brave attempt! Do horror films corrupt? Can sadism be programmed? Is O’Blivion’s distinction between ‘hard media’ and ‘soft media’ valid or useful? Will television prove to be the ultimate aversion therapy? Does the religious phrase ‘the Word made Flesh’ have a new connotation in today’s world? There’s a lot of complex trans-substantiation imagery going on here. Videodrome is a prophetic film, a unique look into the future that has since become reality. The reason lies with its subject matter, the media – the fastest-developing branch of technology in the last few decades. We still essentially fly the same planes and drive the same cars, but our relation to media technology has changed dramatically. The basis of the story can almost be seen as a blueprint for contemporary fears over the effects of media violence.

This is all done with considerable wit and, amazingly, realism. The tacky ambience of down-market television broadcasting is brilliantly evoked, and the television motif is wittily achieved in many areas of the film’s design. Videodrome had an unfortunate initial reception, not even the presence of rock idol Deborah Harry in a kinky role could save it at the box-office. In the long run however, it became so accurate in its predictions of how the media would creep into our daily lives – from first-person shooter games to pay-per-view P*rnography – that it is uncanny. Most films with which reality has caught up look the worse for it but, in the case of Videodrome, it was a vindication of its quality. It may all seem too intellectual for some schlocky fans, and too schlocky for some intellectuals but, let’s be honest, if Cronenberg kept making films like this his audience would have remained extremely limited indeed. With that thought in mind I’ll thank you for reading, and look forward to your company next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

This is all done with considerable wit and, amazingly, realism. The tacky ambience of down-market television broadcasting is brilliantly evoked, and the television motif is wittily achieved in many areas of the film’s design. Videodrome had an unfortunate initial reception, not even the presence of rock idol Deborah Harry in a kinky role could save it at the box-office. In the long run however, it became so accurate in its predictions of how the media would creep into our daily lives – from first-person shooter games to pay-per-view P*rnography – that it is uncanny. Most films with which reality has caught up look the worse for it but, in the case of Videodrome, it was a vindication of its quality. It may all seem too intellectual for some schlocky fans, and too schlocky for some intellectuals but, let’s be honest, if Cronenberg kept making films like this his audience would have remained extremely limited indeed. With that thought in mind I’ll thank you for reading, and look forward to your company next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews