SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

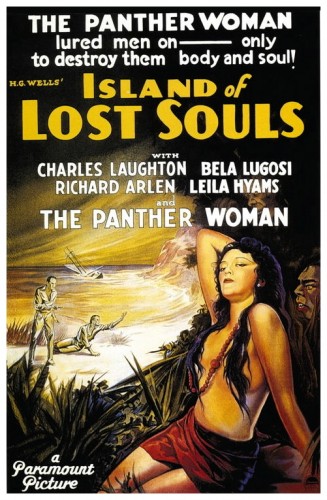

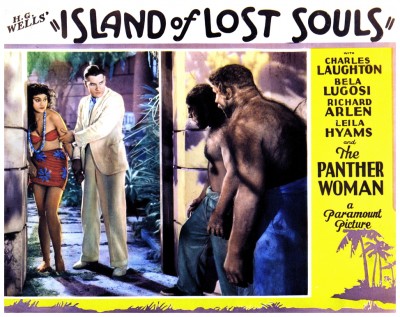

“After his ship goes down, Edward Parker is rescued at sea. Parker gets into a fight with Captain Davies of the Apia and the Captain tosses him overboard while making a delivery to the tiny tropical island of Doctor Moreau. Parker discovers that Moreau has good reason to be so secretive on his lonely island. The doctor is a whip-cracking task master to a growing population of his own gruesome human/animal experiments. He does have one prize result, Lota the beautiful panther woman. Parker’s fortunes for escape look up after his fiancée Ruth finds him with the help of fearless Captain Donohue. However, when Moreau’s tribe of near-humans rises up to rebel, no one is safe…”

REVIEW:

First published in 1896 The Island Of Doctor Moreau is, according to its author H.G. Wells, “An exercise in youthful blasphemy.” The story is narrated by a character named Edward Prendick, a shipwrecked man rescued by a passing boat who is left on the island home of Doctor Moreau, who creates human-like beings from animals using vivisection and other surgical techniques. The novel deals with a number of philosophical themes including the nature of pain and cruelty, moral responsibility, human identity and mankind’s interference with ‘God’s work’. There was growing interest in Europe regarding degeneration and vivisection at the time, and several committees were formed (the first of many) to address issues such as cruelty to animals.

The first film adaptation of the novel was a short French film entitled L’Ile d’Epouvante (1913). The 23-minute two-reel movie was made by Joe Hamman in 1911 but it sat on a shelf for two years gathering dust until it was picked up by American distributor George Klaine who re-named it The Island Of Terror. By the thirties, Hollywood had become terribly enthusiastic about horror films, and the boom had begun. The the first half of the decade was a good time for the Hollywood Gothic and the archetypal Mad Scientist. In addition to the Universal Studio films Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932) and The Invisible Man (1933), there was also Doctor X (1932) from Warner Brothers and Doctor Jekyll And Mister Hyde (1931) from Paramount Pictures.

The first film adaptation of the novel was a short French film entitled L’Ile d’Epouvante (1913). The 23-minute two-reel movie was made by Joe Hamman in 1911 but it sat on a shelf for two years gathering dust until it was picked up by American distributor George Klaine who re-named it The Island Of Terror. By the thirties, Hollywood had become terribly enthusiastic about horror films, and the boom had begun. The the first half of the decade was a good time for the Hollywood Gothic and the archetypal Mad Scientist. In addition to the Universal Studio films Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932) and The Invisible Man (1933), there was also Doctor X (1932) from Warner Brothers and Doctor Jekyll And Mister Hyde (1931) from Paramount Pictures.

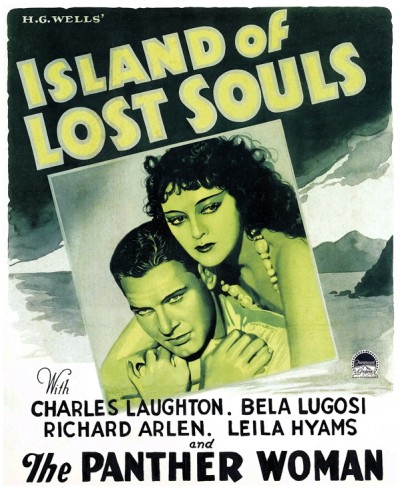

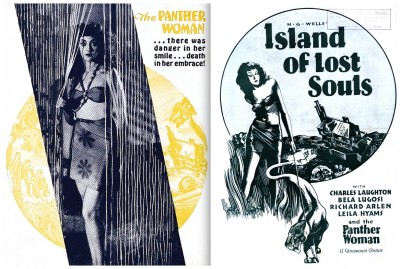

Also from Paramount came Island Of Lost Souls (1932), combining Mad Scientists, man-made monsters and the theme of the man-beast all into one. It was, of course, based on Wells’ novel and marked the first time that one of his works had received the full Hollywood treatment. In 1925 Cecil B. DeMille had purchased the rights to War Of The Worlds for Paramount but the obvious problems in transferring the story to the screen caused DeMille to abandon the project altogether. In 1930 Paramount actually offered it to the Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein but, though it reached the script stage, he also withdrew from the project. Paramount again tried unsuccessfully to make the film in 1932, but it would be another two decades before a version (by George Pal) would finally reach the screen.

Also from Paramount came Island Of Lost Souls (1932), combining Mad Scientists, man-made monsters and the theme of the man-beast all into one. It was, of course, based on Wells’ novel and marked the first time that one of his works had received the full Hollywood treatment. In 1925 Cecil B. DeMille had purchased the rights to War Of The Worlds for Paramount but the obvious problems in transferring the story to the screen caused DeMille to abandon the project altogether. In 1930 Paramount actually offered it to the Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein but, though it reached the script stage, he also withdrew from the project. Paramount again tried unsuccessfully to make the film in 1932, but it would be another two decades before a version (by George Pal) would finally reach the screen.

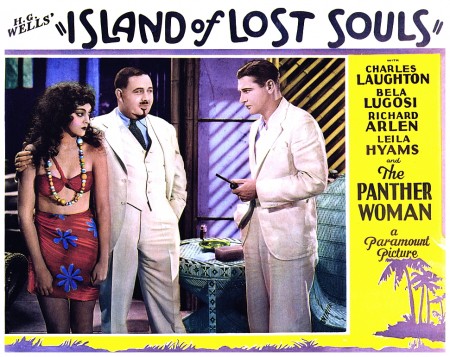

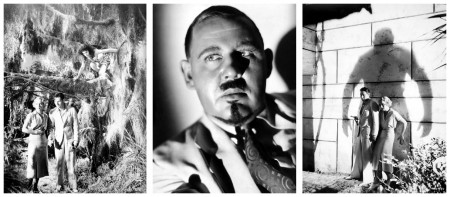

The script of Island Of Lost Souls was written by Waldemar Young and Philip Wylie, the latter being a science fiction writer himself (ironically, Wylie’s novel When Worlds Collide was bought by Paramount in 1934 as a possible project for DeMille but, once again, it was George Pal who finally brought it to the screen in 1951). Young and Wylie diluted much of the impact of Wells’ book and inserted a typical Hollywood love interest but, for all their alterations, the film remains relatively faithful to Wells’ themes. Shipwrecked castaway Edward Parker (Richard Arlen) is picked up by a ship delivering livestock to a small island inhabited by a mysterious doctor named Moreau (Charles Laughton). Parker complains about the captain’s treatment of his passengers, so is tossed overboard and into Moreau’s boat. It is later discovered that Moreau has surgically transformed dozens of wild beasts into horrible-looking ‘manimals’ capable of walking on two legs and talking.

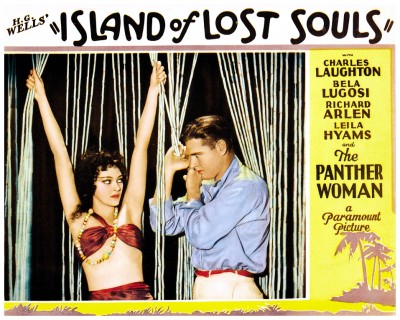

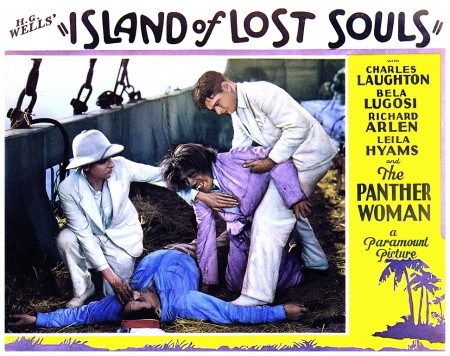

Moreau keeps his manimals in check with a set of laws that, if broken, means a session in the dreaded House Of Pain, and we are often reminded of these rules by the leader of the beast-men, the appropriately named Sayer Of The Law (Bela Lugosi). Moreau introduces him to Lota (Kathleen Burke), a beautiful and gentle girl who, at first, seems a little backward. The doctor reveals that Lota is the only woman on the island, but forgets to mention that she is actually derived from a panther. Later Moreau tells his assistant Mongomery (Arthur Hohl) that Lota is becoming more human due to her attraction to Parker. To keep Parker around to continue the process, Moreau has the only boat destroyed and blames it on his manimals. As the evil vivisectionist Doctor Moreau attempting to transform animals into men using crude and barbaric methods, Charles Laughton gives an absolutely hypnotic performance. A leering whip-cracking monster, he is far more terrifying than his hapless creations, but he isn’t really a Mad Scientist because he knows exactly what he’s doing, which makes him even more disturbing.

Of course he has nothing to do with Wells’ original character, whose cruelty springs from a scientific zeal that makes him oblivious to the feelings of his subjects. Wells’ was quite outspoken in his dislike of the film, stating that the overt horror elements overshadowed his story’s deeper philosophical meaning, and he has a point. Laughton’s Moreau is just plain evil, and he obviously relishes every moment of it. His performance, along with the atmospheric island jungle settings (the exteriors were actually filmed outdoors rather than inside a studio, which was unusual for an early ‘talkie’) and a better-than-average script directed by Erle Kenton help to make Island Of Lost Souls a truly memorable film. Modern-day audiences are often surprised by some truly offensive content including torture, animal cruelty, and the seduction of Parker by the panther woman.

Moreau is obviously betting on the human Parker impregnating the animal Lota, which is certainly one of the more revolting story-lines in cinematic history, so much so that it was refused certification three times by the British Board Of Film Censors in 1933, 1951 and 1957. The reason for the initial ban was due to the scenes of vivisection, and subsequent rejections were influenced by the Cinematograph Films Act of 1937 which forbids the portrayal of cruelty to animals in feature films released in Britain. They also objected to Moreau’s line: “Do you know what it means to feel like God?” The film was eventually passed in the United Kingdom in 1958 with an ‘X’ certificate after certain cuts were made, and was later classified as ‘PG’ when released on DVD in 2011 with the removed footage reinstated.

Despite being an atmospheric horror film, you may find yourself unintentionally giggling at a passage of dialogue midway through the film. Why? Because this is where the infamous cliche ‘The natives are restless’ comes from. It actually goes like this:

Ruth (Leila Hyams) – “What’s that?”

Moreau – “The natives. They have a curious ceremony. Mister Parker has witnessed it.”

Ruth – “Tell us about it, Edward.”

Parker – “Oh, it’s…it’s nothing.”

Moreau – “They are restless tonight.”

There have been at least three attempts to film Wells’ novel since Island Of Lost Souls. In The Twilight People (1973), a scientist kidnaps a man and transports him to an island, intent on turning him into a super-being. The man obviously doesn’t like this idea, so he tries to escape with the help of the scientist’s daughter and a band of half-human, half-animal creatures. The most interesting aspect of this particular version is the appearance of Pam Grier as the Panther Woman. The Island Of Doctor Moreau (1977) featured good makeups and a strong cast, including Richard Basehart as Sayer Of The Law, Barbara Carrera as the Panther Woman, and Burt Lancaster as the perfect Moreau, matching Wells’ original character exactly in physical appearance and scientific zeal.

The most recent adaptation of The Island Of Doctor Moreau (1996) was a huge disappointment starring Val Kilmer, Fairuza Balk and Ron Perlman with Marlon Brando as an extremely lacklustre Moreau. Grossing less than US$50 million at the box-office, barely covering its budget, it received a half-dozen Razzie award nominations including Worst Film and Worst Director, while Brando won the award for Worst Supporting Actor. The production was plagued from the beginning: last-minute director substitutes; constant script re-writes; Kilmer was going through a divorce; and Brando had to deal with both his daughter’s suicide and a nuclear test being performed near his privately-owned island home. Basically, they all got on each other’s nerves and refused to ever work with each other again, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll politely ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to give you another swift kick in the good-taste unit with more terror-filled excursions to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

The most recent adaptation of The Island Of Doctor Moreau (1996) was a huge disappointment starring Val Kilmer, Fairuza Balk and Ron Perlman with Marlon Brando as an extremely lacklustre Moreau. Grossing less than US$50 million at the box-office, barely covering its budget, it received a half-dozen Razzie award nominations including Worst Film and Worst Director, while Brando won the award for Worst Supporting Actor. The production was plagued from the beginning: last-minute director substitutes; constant script re-writes; Kilmer was going through a divorce; and Brando had to deal with both his daughter’s suicide and a nuclear test being performed near his privately-owned island home. Basically, they all got on each other’s nerves and refused to ever work with each other again, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll politely ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to give you another swift kick in the good-taste unit with more terror-filled excursions to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews