SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Commander Kit Draper and Colonel Dan McReady are orbiting Mars in an exploratory surveyor. A malfunction forces them to eject with only Draper and a monkey named Mona surviving. Draper must learn to survive in this hostile environment fighting thirst, hunger and even hostile aliens if he expects to see home again.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Genre filmmaker Byron Haskin is probably best remembered today for directing The War Of The Worlds (1953), one of many films where he teamed with producer George Pal. In his early career, Haskin was primarily a special effects artist who worked on an amazing fifty films in less than a decade, from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) to Arsenic And Old Lace (1944), and was eventually put in charge of the Warner Brothers special effects department. During his tenure there he earned three Oscar nominations for his effects work, and was even recognised with a special Scientific/Technical Award citation for developing a rear-projection system used in effects photography.

In the late forties Haskin turned to directing, and helmed Walt Disney‘s first ever live-action feature Treasure Island (1950). Soon after that he began his collaboration with George Pal with The War Of The Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954), Conquest Of Space (1955) and The Power (1968). His career in television included directing six of the best episodes of The Outer Limits during the early sixties, including the highly regarded Demon With A Glass Hand and The Architects Of Fear. He also co-produced the original Star Trek pilot The Cage, but Haskin’s most personal contribution to the genre is the science fiction adventure Robinson Crusoe On Mars (1964), which he also co-produced and photographed.

In the late forties Haskin turned to directing, and helmed Walt Disney‘s first ever live-action feature Treasure Island (1950). Soon after that he began his collaboration with George Pal with The War Of The Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954), Conquest Of Space (1955) and The Power (1968). His career in television included directing six of the best episodes of The Outer Limits during the early sixties, including the highly regarded Demon With A Glass Hand and The Architects Of Fear. He also co-produced the original Star Trek pilot The Cage, but Haskin’s most personal contribution to the genre is the science fiction adventure Robinson Crusoe On Mars (1964), which he also co-produced and photographed.

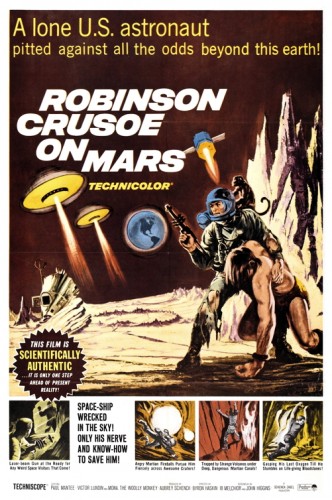

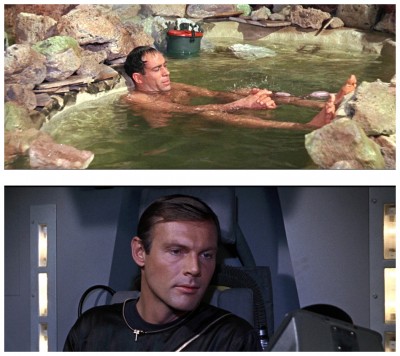

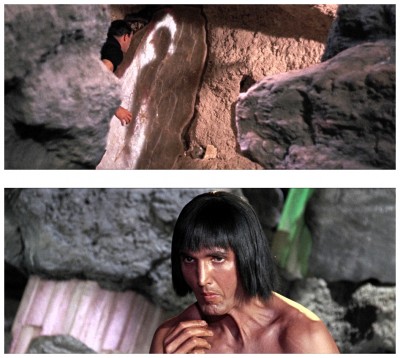

Robinson Crusoe On Mars is, of course, a futuristic adaptation of Daniel Defoe‘s classic novel, written for the screen by Ib Melchoir and John C. Higgins, and starring Paul Mantee as Christopher Draper, commander of a two-man spaceship accompanied by Colonel Dan McReady (Adam West). Just as Mars Gravity Probe One is about to reach its target, the crew are forced to burn up their remaining fuel to avoid collision with a meteor. The two men are forced to exit the spacecraft and are subsequently stranded on Mars. McReady is killed during the landing, and Draper is left struggling to survive in the barren alien environment, his only companion a tiny female monkey named Mona (played by a male monkey named Barney, indulging in Hollywood’s second-favourite pass-time, cross-dressing), and lives for months in a small cave renewing his air supply by heating Martian rocks that give off oxygen. He also suffers from nightmares, being haunted at night by ghostly images of his dead colleague McReady.

Robinson Crusoe On Mars is, of course, a futuristic adaptation of Daniel Defoe‘s classic novel, written for the screen by Ib Melchoir and John C. Higgins, and starring Paul Mantee as Christopher Draper, commander of a two-man spaceship accompanied by Colonel Dan McReady (Adam West). Just as Mars Gravity Probe One is about to reach its target, the crew are forced to burn up their remaining fuel to avoid collision with a meteor. The two men are forced to exit the spacecraft and are subsequently stranded on Mars. McReady is killed during the landing, and Draper is left struggling to survive in the barren alien environment, his only companion a tiny female monkey named Mona (played by a male monkey named Barney, indulging in Hollywood’s second-favourite pass-time, cross-dressing), and lives for months in a small cave renewing his air supply by heating Martian rocks that give off oxygen. He also suffers from nightmares, being haunted at night by ghostly images of his dead colleague McReady.

The film succeeds in capturing society’s desire to send a man to Mars and conveys a sense of excitement at the discovery of being on another planet. Comedy relief is provided by the monkey, as Mona is able to decipher situations before her seemingly superior human companion. At one point, Mona discovers a cave that supplies an alien plant-life which provides a source of nourishment for the astronaut. Perhaps this suggests that in a time of human ignorance or obliviousness, a more simple-minded creature might actually have the answer to life, the universe and everything.

The film succeeds in capturing society’s desire to send a man to Mars and conveys a sense of excitement at the discovery of being on another planet. Comedy relief is provided by the monkey, as Mona is able to decipher situations before her seemingly superior human companion. At one point, Mona discovers a cave that supplies an alien plant-life which provides a source of nourishment for the astronaut. Perhaps this suggests that in a time of human ignorance or obliviousness, a more simple-minded creature might actually have the answer to life, the universe and everything.

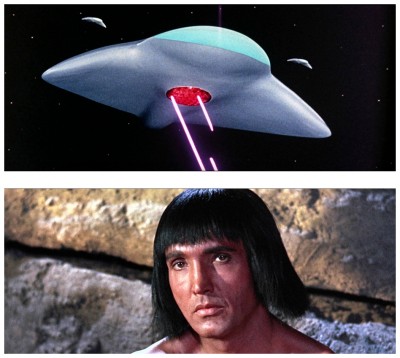

Up until this point the film is a relatively realistic and convincing study of one man’s fight to overcome hostile surroundings and mental breakdown, but then an alien spaceship arrives and the film unfortunately degenerates into pure hokum. Spying on the aliens, Draper observes that they keep human slaves and, when one of them escapes, Draper helps him avoid the flying drones sent out from the alien mothership. The slave (Victor Lundin), who looks like a South American Indian, becomes Draper’s ‘Man Friday’ and together they make a long trek to the Martian polar ice cap where they await rescue by another American spaceship.

Up until this point the film is a relatively realistic and convincing study of one man’s fight to overcome hostile surroundings and mental breakdown, but then an alien spaceship arrives and the film unfortunately degenerates into pure hokum. Spying on the aliens, Draper observes that they keep human slaves and, when one of them escapes, Draper helps him avoid the flying drones sent out from the alien mothership. The slave (Victor Lundin), who looks like a South American Indian, becomes Draper’s ‘Man Friday’ and together they make a long trek to the Martian polar ice cap where they await rescue by another American spaceship.

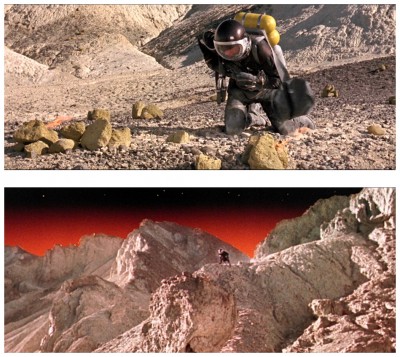

Director Haskin strives to keep close to Defoe’s original treatment on survival and loneliness in extreme conditions and the nature of friendship in a master-servant relationship without ever being sentimental or overblown, as when Draper shouts out in frustration, “Mister Echo, go to hell!” Haskin continues to captivate fantasy lovers everywhere with his graphically designed masterpiece into the unknown. The hostile landscape of Mars was fittingly supplied by the location filming in California’s Death Valley National Park at the suitable lifeless Zabriskie Point. The highly regarded Australian trade magazine Cinema Papers (March 1975) spoke to Mr. Haskin about working on Robinson Crusoe On Mars: “I consider that film the best I’ve ever done, because it had basically one of the soundest stories ever written. Unfortunately, the film did not become a hit because of the bad judgment of the producer and the releasing company. I fought like a tiger to get rid of the silly-ass title but to no avail.”

Director Haskin strives to keep close to Defoe’s original treatment on survival and loneliness in extreme conditions and the nature of friendship in a master-servant relationship without ever being sentimental or overblown, as when Draper shouts out in frustration, “Mister Echo, go to hell!” Haskin continues to captivate fantasy lovers everywhere with his graphically designed masterpiece into the unknown. The hostile landscape of Mars was fittingly supplied by the location filming in California’s Death Valley National Park at the suitable lifeless Zabriskie Point. The highly regarded Australian trade magazine Cinema Papers (March 1975) spoke to Mr. Haskin about working on Robinson Crusoe On Mars: “I consider that film the best I’ve ever done, because it had basically one of the soundest stories ever written. Unfortunately, the film did not become a hit because of the bad judgment of the producer and the releasing company. I fought like a tiger to get rid of the silly-ass title but to no avail.”

“We filmed most of it in Death Valley. People have shot movies there before, but usually down in the valley. We shot our stuff up on the ridges so that we’d have the sky in the backgrounds. Larry Butler, who later did the effects in Marooned (1969) over at Columbia, did the effects on Crusoe as a favour to me. He has an optical printer you wouldn’t believe, and he removed all our skies for us. We had to convince audiences dramatically that they were not seeing Earth. A blue sky would have been a dead giveaway, so he matted in an orange-red colour. The skies up in Death valley were very blue and gave us good traveling matte outlines. So all that we shot there provided its own matte-line and we simply added the orange-red.”

“We filmed most of it in Death Valley. People have shot movies there before, but usually down in the valley. We shot our stuff up on the ridges so that we’d have the sky in the backgrounds. Larry Butler, who later did the effects in Marooned (1969) over at Columbia, did the effects on Crusoe as a favour to me. He has an optical printer you wouldn’t believe, and he removed all our skies for us. We had to convince audiences dramatically that they were not seeing Earth. A blue sky would have been a dead giveaway, so he matted in an orange-red colour. The skies up in Death valley were very blue and gave us good traveling matte outlines. So all that we shot there provided its own matte-line and we simply added the orange-red.”

The superb photography coupled with Albert Whitlock‘s matte paintings combine for one of the best-looking Martian landscapes ever conceived, all raw colours and horrifically stark dust-blown vistas. Utilising the relatively new photographic techniques of vast Techniscope and Technicolor, Robinson Crusoe On Mars remains an imaginative marvel of classic science fiction cinema. And it’s with that rather upbeat thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to sterilise you with fear during another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

The superb photography coupled with Albert Whitlock‘s matte paintings combine for one of the best-looking Martian landscapes ever conceived, all raw colours and horrifically stark dust-blown vistas. Utilising the relatively new photographic techniques of vast Techniscope and Technicolor, Robinson Crusoe On Mars remains an imaginative marvel of classic science fiction cinema. And it’s with that rather upbeat thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to sterilise you with fear during another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

This film would make a fine companion piece to the (surprisingly faithful!) adaptation of ‘Treasure Island in Outer Space’ (Dir: Antonio Margheriti – 1987).