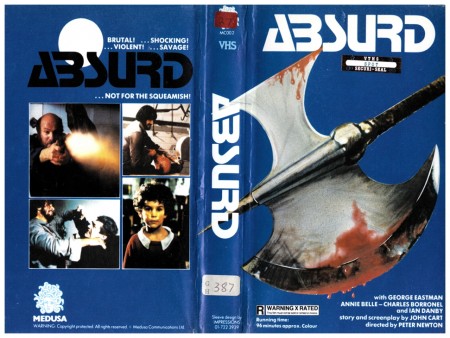

‘Video Nasty‘ was a term coined in Britain around 1982 which applied to certain films distributed on video cassette that were criticised by the media and various religious organisations for their violent content. While cinema violence had been regulated by the British Board of Film Censorship for many years, the lack of regulations for video sales (combined with the claim that any film could be viewed by impressionable kiddies) sparked a massive public debate. Most Video Nasties were low-budget horror films produced in Italy and America. Several major studio productions were banned on video, falling under the legislation designed to control the distribution of violent videos. Major film distributors were slow to embrace the new medium of video tape so, like the drive-in market of the fifties, the video market became flooded with low-budget horror films. Some of these films were passed by the BBFC while others were refused certification, defining ‘obscenity’ as any film that might “deprave and corrupt persons who are likely, having regard to all relevant circumstances, to read, see or hear the matter contained or embodied in it.” This definition was open to wide interpretation and the choice of titles seized appeared to be completely arbitrary – one raid confiscated hundreds of copies of the Dolly Parton musical The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas (1982) mistaking it for a p*rno.

‘Video Nasty‘ was a term coined in Britain around 1982 which applied to certain films distributed on video cassette that were criticised by the media and various religious organisations for their violent content. While cinema violence had been regulated by the British Board of Film Censorship for many years, the lack of regulations for video sales (combined with the claim that any film could be viewed by impressionable kiddies) sparked a massive public debate. Most Video Nasties were low-budget horror films produced in Italy and America. Several major studio productions were banned on video, falling under the legislation designed to control the distribution of violent videos. Major film distributors were slow to embrace the new medium of video tape so, like the drive-in market of the fifties, the video market became flooded with low-budget horror films. Some of these films were passed by the BBFC while others were refused certification, defining ‘obscenity’ as any film that might “deprave and corrupt persons who are likely, having regard to all relevant circumstances, to read, see or hear the matter contained or embodied in it.” This definition was open to wide interpretation and the choice of titles seized appeared to be completely arbitrary – one raid confiscated hundreds of copies of the Dolly Parton musical The Best Little Whorehouse In Texas (1982) mistaking it for a p*rno.

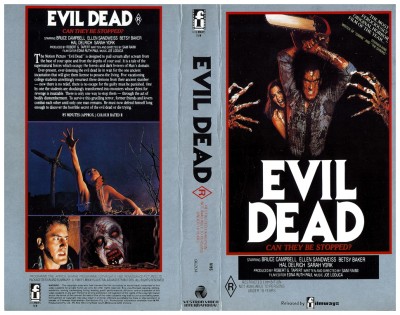

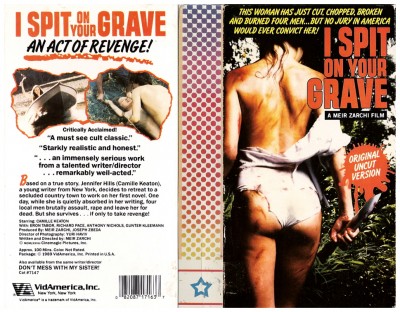

Video tapes of The Evil Dead (1981) were also seized and destroyed by police. In fact, The Evil Dead could legally be shown in British cinemas – the BBFC had passed it – and was premiered at the London International Film Festival, but BBFC legislation in 1984 proscribed graphic horror films from being sold or rented on video tape, even if they had been approved for theatrical release. Virtually no-one spoke out in public to point out that there are fine distinctions to be made in this moral minefield. Films like I Spit On Your Grave (1978), with scenes of graphic mutilation and prolonged sexual sadism in a supposedly realistic, almost documentary context, might very properly be condemned and banned. These were films that exploited the dark cowardice of sado-voyeurs. But when the context is clearly fantastic – when the graphic mutilations appear, so to speak, within the inverted commas provided by the film’s fantastic nature, then surely the question is very different.

Video tapes of The Evil Dead (1981) were also seized and destroyed by police. In fact, The Evil Dead could legally be shown in British cinemas – the BBFC had passed it – and was premiered at the London International Film Festival, but BBFC legislation in 1984 proscribed graphic horror films from being sold or rented on video tape, even if they had been approved for theatrical release. Virtually no-one spoke out in public to point out that there are fine distinctions to be made in this moral minefield. Films like I Spit On Your Grave (1978), with scenes of graphic mutilation and prolonged sexual sadism in a supposedly realistic, almost documentary context, might very properly be condemned and banned. These were films that exploited the dark cowardice of sado-voyeurs. But when the context is clearly fantastic – when the graphic mutilations appear, so to speak, within the inverted commas provided by the film’s fantastic nature, then surely the question is very different.

In the case of The Evil Dead, for example, the action was so highly conventionalised, so fantastically theatrical, that its undisputed violence is closer to that of a Tom And Jerry cartoon than the brutality of I Spit On Your Grave. The latter typifies the really obscene form of ‘Nasty’ in its emphasis on gloating observation, like long scenes of perverse rape or castration, for example. During the eighties, genre cinema seldom placed any emphasis on sexual mutilation, while real Video Nasties place enormous emphasis specifically on this kind of brutality, and on women generally as sexual victims and/or avengers. The ‘tree rape’ scene in The Evil Dead is a brief and rather absurd sequence in admittedly bad taste, while the rape scenes in real Video Nasties tend to be disgracefully prolonged. At the time, the graphic violence of genre cinema was not notably sexist and, even when it was sexist, it was rarely sexual. Filmmaker David Cronenberg once told me that the horror of the body, the horror of decay, is a legitimate and important theme that genre cinema is peculiarly well-suited to contemplate. Art must be able to incorporate ugliness or violence in some manner, and the wholly theatrical rigid conventions of ‘Grand Guignol‘ visceral horror surely provide an acceptable ‘distanced’ way of registering the body’s vulnerability. After all, our viscera are separated from the outside world by the thinnest of partitions, and it may help to be reminded occasionally of what lies beneath the skin.

In the case of The Evil Dead, for example, the action was so highly conventionalised, so fantastically theatrical, that its undisputed violence is closer to that of a Tom And Jerry cartoon than the brutality of I Spit On Your Grave. The latter typifies the really obscene form of ‘Nasty’ in its emphasis on gloating observation, like long scenes of perverse rape or castration, for example. During the eighties, genre cinema seldom placed any emphasis on sexual mutilation, while real Video Nasties place enormous emphasis specifically on this kind of brutality, and on women generally as sexual victims and/or avengers. The ‘tree rape’ scene in The Evil Dead is a brief and rather absurd sequence in admittedly bad taste, while the rape scenes in real Video Nasties tend to be disgracefully prolonged. At the time, the graphic violence of genre cinema was not notably sexist and, even when it was sexist, it was rarely sexual. Filmmaker David Cronenberg once told me that the horror of the body, the horror of decay, is a legitimate and important theme that genre cinema is peculiarly well-suited to contemplate. Art must be able to incorporate ugliness or violence in some manner, and the wholly theatrical rigid conventions of ‘Grand Guignol‘ visceral horror surely provide an acceptable ‘distanced’ way of registering the body’s vulnerability. After all, our viscera are separated from the outside world by the thinnest of partitions, and it may help to be reminded occasionally of what lies beneath the skin.

Video Nasties deal with the violation of bodies, of minds, of normality, but very few of these films implicitly invited the audience to join with the oppressor, the violator, the villain. My old friend, author Gene Wolfe, told me back in 1985, “I think that all of us have a desire to experience the worst so that we can tell ourselves that we can survive the worst. That is part of the appeal of horror.” The audiences of graphic horror films may be quite innocent of sadism. They are voluntarily undertaking a kind of rite-of-passage, which is just as likely to be as cleansing and cathartic as it is to be corrupting. The entertainment to be derived from these films need not be sick – the source of the entertainment is our knowledge that the events we are witnessing are a fiction, just as riding a roller-coaster is not the same as actually plunging off a cliff. Our relief at this, along with the knowledge that we can go home afterwards and have a glass of Absinthe, constitutes a major part of of our response. For this reason, most so-called Video Nasties – very obviously fictions – should not be categorised in the same pigeonhole as certain Video Nasties presented in the realist mode.

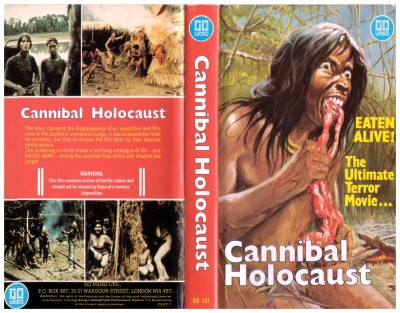

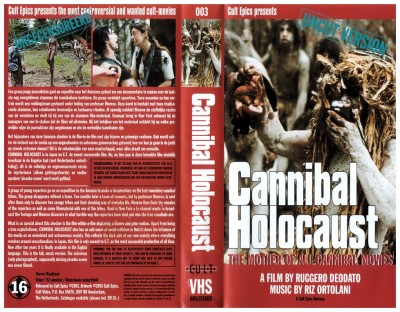

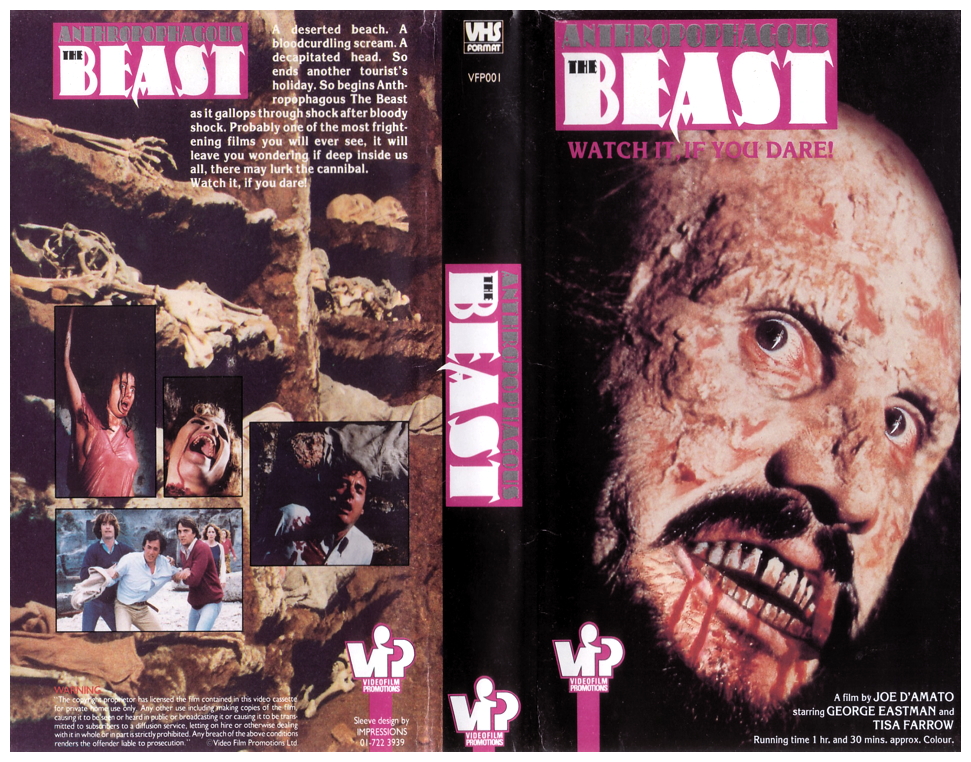

For instance, there was a plethora of cannibal films of which Cannibal Holocaust (1980) was undoubtedly the most disturbing and impressive, as well as being one of the films responsible for initiating the Video Nasty moral panic in the United Kingdom. In fact, the video was indeed released by Go Video, although not absolutely complete, but most of the atrocity footage was still there. Anthropologist Professor Harold Munro (Robert Kerman) being dispatched to the Amazon jungle in search of a missing documentary film crew comprising of Alan (Gabriel Yorke), Faye (Francesca Ciardi), Jack (Perry Pirkanen) and Mark (Luca Barbareschi). Meeting the Tree People, Munro finds them both aggressive and fearful, but he manages to gain their confidence and soon discovers a gruesome totem constructed from the remains of the film crew and their equipment. This includes cans of film which he takes home to develop. These reveal that the documentary crew had systematically terrorised the tribespeople, raping and murdering them, in order to film atrocity footage which they could then present as showing a conflict between the Tree People and the Swamp People. In the end, the tribespeople turn on their tormentors and extract a hideous revenge which the filmmakers, true ‘professionals’ to the end, manage to capture for posterity in all its revolting detail.

On one level, Cannibal Holocaust is a savage critique of the whole ‘Mondo’ school of film-making. At one point Munro is shown extracts from one of the team’s earlier efforts consisting of a montage of African atrocity footage – a reference to the infamous Africa Addio (1966). A television executive claims proudly, “Everything you saw there was a put-on and the ratings they got were fantastic!” However, as the retrieved footage shows, the crew’s methods go way beyond simply faking events and actually make things happen for the camera to record. These include killing and cutting up a turtle, and setting fire to an entire village: The film crew advance into the village like an invading army, a reflection of My Lai, the real-life Vietnam community which was decimated by an American commando unit. No event, however horrible, is left to go unrecorded. When their guide is bitten on the foot by a snake, the ensuing amputation and cauterisation are captured in loving detail, followed by his death and crude burial. In what they call ‘primitive social surgery’ a heavily pregnant woman is forced to give birth and then murdered, whilst the foetus is buried in mud. Even their own deaths, which involve the castration of Jack, the multiple rape of Faye, and the disemboweling and devouring of them all, are captured in unflinching detail. Here director Ruggero Deodato‘s documentary style really comes into its own with alarming realism, further helped by the clever use of blank film leader, lab marks and all the other paraphernalia of the cutting room.

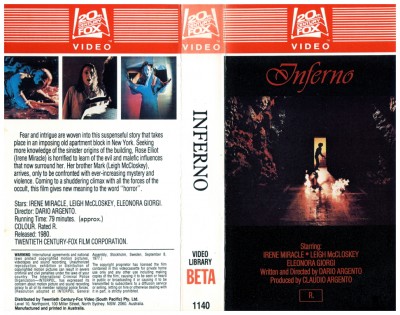

By this time, the French theatre tradition of Grand Guignol had become a specialty of the Italians, under the guidance of filmmakers like Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci, although Argento is the superior craftsman of the two. His Suspiria (1976) is a stylish exercise. Jessica Harper plays the American girl attending a ballet school in a German provincial town. The proprietors of the school are a coven of witches hell-bent on murdering and mutilating their students. The film opens with the heroine, Suzy, leaving a German airport through sliding glass doors and, as she goes through into the wintry night outside, her scarf blows back up around her face as if directed by some unseen hand, but it is only the wind. Set-piece follows set-piece: Girls are picturesquely murdered in art deco settings; one gets her head bisected by a pane of coloured glass; maggots rain from the ceiling; the vast halls of the academy glow with coloured light; we hear a stone bird flapping its wings; a blind man has his throat torn out by his own dog; a student falls into a room surrealistically billowing with great coils of bailing wire; the dead body of a girl with pins in her eyes is reanimated by an invisible witch; art-neuvo irises on a wall hold secrets to hidden passages; whispering can be heard between heavy metal rock songs. The academy is run by Helena Markos, also known as the Mother of Whispers, who is hundreds of years old and looks like it. She is eventually stabbed by a glass dagger – a reference to Argento’s earlier film The Bird With The Crystal Plumage (1970) – plucked from the tail of an ornamental peac**k. The labyrinthine building majestically collapses as Suzy escapes her slow-motion Gothic nightmare.

The flamboyance of Suspiria was sustained in the sequel Inferno (1980), which is mostly set in a New York apartment house, ancient residence of the second of the three witches, the Mother of Darkness. Here, however, the bravura is faltering, the killings more random. This time around, we cannot identify with any one character, because one-by-one they are demolished not long after they are introduced. There is a straining for effect in the killings – attacked by cats, attacked by rats, strangled by the wires of an electronic voice-box – that comes close to being downright ludicrous. Mario Bava did the special effects and was responsible for the most haunting scene, in which a girl wandering through a dank cellar comes across a well in the floor. Insanely entering it to retrieve a dropped brooch, she finds herself swimming in an underwater room, sumptuously furnished. Through the rippling blue water we see paintings, carpets, grand settees. It is a moment of authentic magic as its subject. Argento is not terribly interested in linear narrative. For him, magic is arbitrary and inexplicable, the result being a fragmentation so extreme as to defy analysis of what it all might mean.

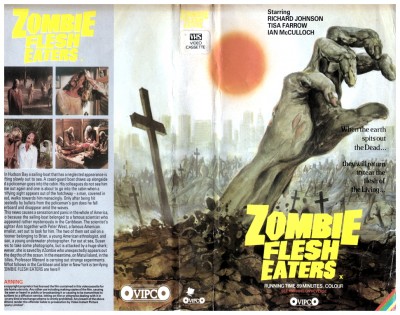

Lucio Fulci made the sort of movies that nice people did not want to see. Perhaps mercifully, as most nice people don’t even know they existed. He is actually the innocent victim of Italian ‘Giallo‘ and his childlike wish is to show successive horrors each one of which is worse than you could have ever imagined. He is the master of what my old friend Stephen King called the ‘Gross-Out’ in his non-fiction book Danse Macabre. The crude delight Fulci so obviously takes in his special effects probably has a very long history – even William Shakespeare used animal entrails as usefully revolting theatre props. Fulci’s Zombie Flesh Eaters (1979) features members of the living dead with table manners so revolting as to make George Romero‘s zombies look like toffee-nosed gentlemen by contrast. In a neat turn on Jaws (1975), one of them even makes a meal of a shark. Viewers of the uncensored Video Nasty could witness the horrifying events, such as the gouging-out of an eye, in loving close-up, as well as heads and arms bursting upwards like thick weeds at people passing by.

Lucio Fulci made the sort of movies that nice people did not want to see. Perhaps mercifully, as most nice people don’t even know they existed. He is actually the innocent victim of Italian ‘Giallo‘ and his childlike wish is to show successive horrors each one of which is worse than you could have ever imagined. He is the master of what my old friend Stephen King called the ‘Gross-Out’ in his non-fiction book Danse Macabre. The crude delight Fulci so obviously takes in his special effects probably has a very long history – even William Shakespeare used animal entrails as usefully revolting theatre props. Fulci’s Zombie Flesh Eaters (1979) features members of the living dead with table manners so revolting as to make George Romero‘s zombies look like toffee-nosed gentlemen by contrast. In a neat turn on Jaws (1975), one of them even makes a meal of a shark. Viewers of the uncensored Video Nasty could witness the horrifying events, such as the gouging-out of an eye, in loving close-up, as well as heads and arms bursting upwards like thick weeds at people passing by.

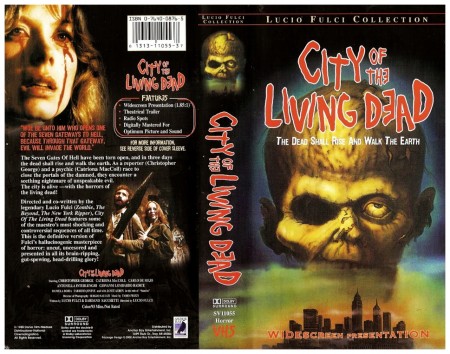

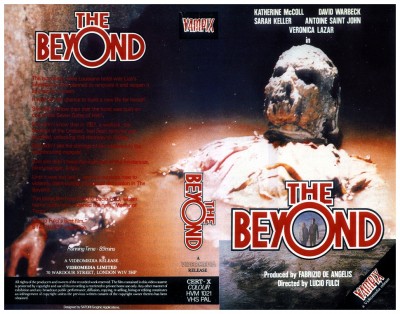

City Of The Living Dead (1980) carries physical horror into the realms of frank disbelief: A girl is buried alive and her careless rescuer swings a pick through the coffin within millimetres of her face in a series of thunderous blows; A dead priest glares red-eyed at a young woman who obligingly vomits up all her intestines at him; The local idiot boy becomes fascinated with a power drill; Zombie hands reach from outside the frame to pluck off the backs of people’s heads and paddle about in the brains beneath. More ambitious in scope was The Beyond (1981), in which a New Orleans hotel is built over one of the gates of Hell. By some sort of Lovecraftian geometry, it’s linked by a short flight of stairs to the mortuary of the hospital some miles away where killer zombies abound. Supernatural spiders live in the library, and a strange blind woman lives in a fine house that, in the daylight, is decayed and empty – she is later mutilated by her own guide dog. Finally the survivors walk through the cellar into the desert of Hell itself, which reflects the oil painting we see at the beginning of the film.

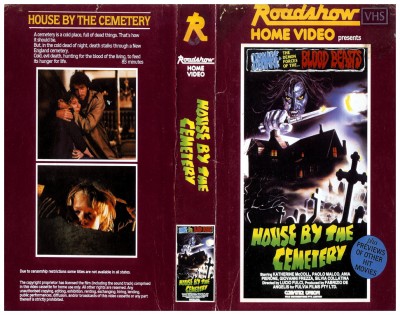

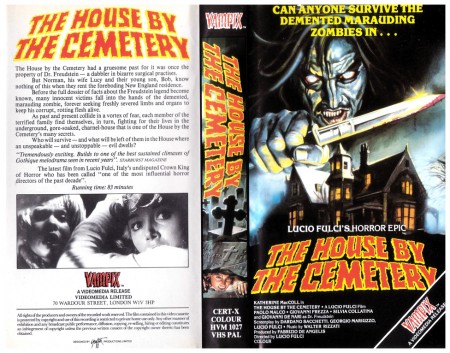

In fact, in his own repulsive way, Fulci became a force to be reckoned with. The House By The Cemetery (1981), in which the sinister Doctor Freudstein plays with corpses in the cellar – indeed, he is one himself – is at moments both witty and inventive. The unfortunates who live in this house all contrive to finish up in the cellar (one takes an alarming short-cut straight through the floor), and there is also an especially vicious vampire bat to be coped with. The treatment of children in the film is surprisingly tender, especially the scenes of the little boy making friends with the blank little girl (long dead) who exists in the timeless limbo to which he escapes from the cellar at the end, with an epigraph taken from Henry James. I’m tempted to defend Fulci’s bottom-of-the-barrel sado-exploitation Video Nasties for their macabre joviality, all papier mache and sheep’s guts, and the filmmaker’s ill-advised but admirable insistence on breaking every rule of coherent narrative in order to create the illogicality of a nightmare but, on mature consideration, I won’t.

In fact, in his own repulsive way, Fulci became a force to be reckoned with. The House By The Cemetery (1981), in which the sinister Doctor Freudstein plays with corpses in the cellar – indeed, he is one himself – is at moments both witty and inventive. The unfortunates who live in this house all contrive to finish up in the cellar (one takes an alarming short-cut straight through the floor), and there is also an especially vicious vampire bat to be coped with. The treatment of children in the film is surprisingly tender, especially the scenes of the little boy making friends with the blank little girl (long dead) who exists in the timeless limbo to which he escapes from the cellar at the end, with an epigraph taken from Henry James. I’m tempted to defend Fulci’s bottom-of-the-barrel sado-exploitation Video Nasties for their macabre joviality, all papier mache and sheep’s guts, and the filmmaker’s ill-advised but admirable insistence on breaking every rule of coherent narrative in order to create the illogicality of a nightmare but, on mature consideration, I won’t.

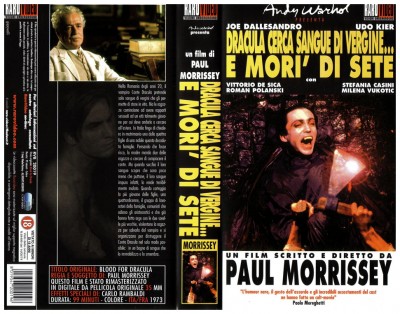

It wasn’t only the Italians who liked this sort of stuff. There is a strong case for arguing that the first real Video Nasties were two films produced in Italy by American ‘enfant terrible’ Andy Warhol who, feeling too languid to direct them himself and handed the job over to Paul Morrissey – both writing and direction. Blood For Dracula (1973) was a mildly p*rnographic vampire parody starring Udo Kier as Dracula, who is in terrible trouble because he needs the blood of virgins (pronounced ‘wirgins’) and there aren’t any left locally. He travels by limousine to Italy, where he moves in with a decadent aristocratic family (they hope to marry off one of their many daughters) and attempts to vampirise the sisters, one-by-one, having been assured that they’re all virgins. Thanks to the heroic efforts of the stud gardener (Joe Dallesandro), he is mistaken. The polluted blood makes Dracula frightfully sick – he acts as if he suffers terminal tuberculosis throughout the film – and there are extremely long scenes of him vomiting violently. There is also a very bloody finale, so extreme it resembles a scene from Monty Python And The Holy Grail (1975), in which the gardener chops off Dracula’s arms, legs and head. In between the moments of nausea and sexual couplings, there are many tedious moments, despite the implausible cameo role played by Vittoria De Sica.

It wasn’t only the Italians who liked this sort of stuff. There is a strong case for arguing that the first real Video Nasties were two films produced in Italy by American ‘enfant terrible’ Andy Warhol who, feeling too languid to direct them himself and handed the job over to Paul Morrissey – both writing and direction. Blood For Dracula (1973) was a mildly p*rnographic vampire parody starring Udo Kier as Dracula, who is in terrible trouble because he needs the blood of virgins (pronounced ‘wirgins’) and there aren’t any left locally. He travels by limousine to Italy, where he moves in with a decadent aristocratic family (they hope to marry off one of their many daughters) and attempts to vampirise the sisters, one-by-one, having been assured that they’re all virgins. Thanks to the heroic efforts of the stud gardener (Joe Dallesandro), he is mistaken. The polluted blood makes Dracula frightfully sick – he acts as if he suffers terminal tuberculosis throughout the film – and there are extremely long scenes of him vomiting violently. There is also a very bloody finale, so extreme it resembles a scene from Monty Python And The Holy Grail (1975), in which the gardener chops off Dracula’s arms, legs and head. In between the moments of nausea and sexual couplings, there are many tedious moments, despite the implausible cameo role played by Vittoria De Sica.

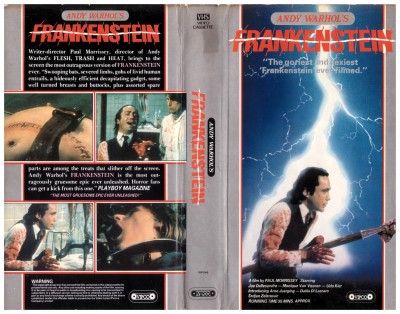

Flesh For Frankenstein (1973), produced in 3-D alongside the 2-D Blood For Dracula, was a bloodthirsty parody featuring ponderously improvised smart-arse dialogue and mild p*rnography, as the stud villager (Joe Dallesandro) carries on the class struggle in bed with Baron Frankenstein’s wife (who also happens to be the Baron’s sister). There’s internal organs strung everywhere in the Baron’s laboratory, a handsome monster with the head of an innocent local virgin boy, and vast amounts of gore. As the necrophile Baron inserts – ahem – a part of his person into the abdominal slit he has carved into one of his latest victims (she is to be the monster’s mate), he says to his assistant, “To know death, Otto, one must f*ck life in the gall bladder.” This is my candidate for Worst Line A Horror Film Ever, although it does sum-up the intellectual level of the film.

Flesh For Frankenstein (1973), produced in 3-D alongside the 2-D Blood For Dracula, was a bloodthirsty parody featuring ponderously improvised smart-arse dialogue and mild p*rnography, as the stud villager (Joe Dallesandro) carries on the class struggle in bed with Baron Frankenstein’s wife (who also happens to be the Baron’s sister). There’s internal organs strung everywhere in the Baron’s laboratory, a handsome monster with the head of an innocent local virgin boy, and vast amounts of gore. As the necrophile Baron inserts – ahem – a part of his person into the abdominal slit he has carved into one of his latest victims (she is to be the monster’s mate), he says to his assistant, “To know death, Otto, one must f*ck life in the gall bladder.” This is my candidate for Worst Line A Horror Film Ever, although it does sum-up the intellectual level of the film.

These decadent jokes against the decadents did extremely well at the box-office – audiences enjoyed the 3-D intestines dangling in their faces – and they definitely had something to do with rendering the Video Nasty acceptable to mainstream viewers. Before you have time to contemplate that last statement, I’ll invite you to please join me next week when I have another opportunity to give you swift kick in the good-taste unit with a terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

These decadent jokes against the decadents did extremely well at the box-office – audiences enjoyed the 3-D intestines dangling in their faces – and they definitely had something to do with rendering the Video Nasty acceptable to mainstream viewers. Before you have time to contemplate that last statement, I’ll invite you to please join me next week when I have another opportunity to give you swift kick in the good-taste unit with a terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

This article starts off with a deeply pretentious tone strongly influenced by the Politically Correct Religion’s belief system. Happily once it’s done passing a very dubious moral judgement on ‘I Spit on Your Grave’ it becomes more of a description piece for other famous works of horror.

I’d say this: Fiction should always be viewed as just that, it’s NOT real. It never was. No work of fiction disturbs me. Sometimes the news (when it’s not completely sensationalized) does. I Spit on Your Grave is in no way immoral or wrong. It is a movie that show violence and the consequences of violence as opposed to the vast majority of popular films which are violent but play down cause and effect. It can be argued that ‘A-Team’ style violence where people are shot without consequences is much more damaging to the viewer’s psyche. However what I’d really argue is this: Damaged people will do damaged things. Whole people will always understand what is real, what is fake and have the proper context for each of them.

As for ‘video nasties’ and censorship that’s really about control. Government and Religions always want more control over their populace. It was never about what’s objectively good, it’s about having power and making use of it to suit your own morality.

Hello, good evening and welcome, Mr Skull!

I can’t thank you enough for reading. It was never meant to be a thorough investigation into the Video Nasties phenomenon, of course, but a general rundown of the best/worst/most unusual films during that era. To quote filmmaker Sam Raimi circa 1990:

“Those guys at the censorship board have their underwear on too tight. It’s completely unacceptable that the government determines what people can and can’t see. I thought we got past all that back in the late thirties and forties. What I don’t like is the superiority and the smug attitude that they can see such things and they won’t be affected by them, they’re superior to everyone else. They can take it, and they’ve seen it, yet they’re making a decision that others are too weak, too emotionally unstable to handle it. Well, what are they talking about? I don’t know, I think they should ban the censor board. That should be the first thing they ban. Actually, the real problem is not a movie like The Evil Dead, because it’s not really important whether that is seen or not by people. The problem is, once the people allow these censors to determine what’s right and wrong for them, once they’ve given them that power, who’s to say that a politically disturbing picture that dithers from the view of the censors politically, shouldn’t it be censored? The people of Britain shouldn’t allow them that power because soon they’ll find that other rights are being taken from them one by one, till they don’t have the right to speak out at all. Where does it all stop? There’s only one absolute freedom, there’s nothing else. You can’t begin limiting input, it’s too dangerous.”

I enjoyed reading the article. I also very much liked the above quote (I hadn’t read Raimi’s opinion on censorship before). I look forward to more of your well informed articles.

Nigel, are you familiar with Martin Barker’s I SPIT ON YOUR GRAVE experiment? He asked his students to imagine a filmic treatment of rape that would convey the horror and avoid titillation. What they came up with was very close to the actual film, he says.

Thanks for reading, Mr. Campbell (one of my favourite horror authors of all-time! Wow!) – I’ve read a few essays by Martin Barker (there’s a very insightful one comparing A Clockwork Orange with Straw Dogs), but was unaware of such an experiment concerning I Spit On Your Grave – must look it up now. It certainly makes sense though.