Mental Hygiene for a Teenage Werewolf

By

Anthony M. Caro

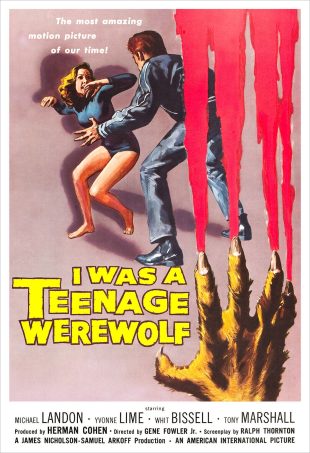

Reviews and reference materials that refer to Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) as a “campy” film are head-scratching. While the absurd Frankenstein follow-up had unintentional comedic elements, Michael Landon’s portrayal of the adolescent lycanthrope Tony Rivers conveys a dark and tragic tale. There’s little to laugh about when watching the teenage werewolf’s plight unfold because things didn’t have to turn out the way they did. Teenager Tony had his struggles and couldn’t overcome them because he didn’t listen to the adults who gave him good advice.

It’s as if Tony’s complicated life is one part classic horror and one part 16mm mental hygiene film.

Teenage Werewolf Lament ‘57

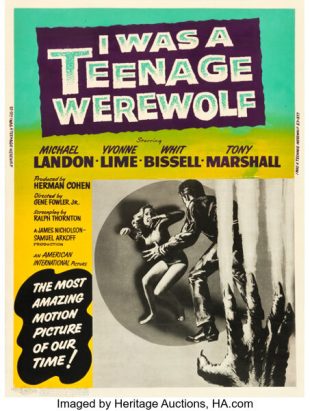

From a cinema history perspective, the release of I Was a Teenage Werewolf stands as a landmark moment in the horror genre. 1957 and 1958 were vital years for horror, as the genre stalled, stepping aside to accommodate the burgeoning science-fiction movement. Flying saucers and over-sized radioactive insects ruled movie theaters as old horror film monsters stopped being scary in the shadow of the atomic bomb. New films that featured classic horror monsters often replaced supernatural elements with scientific ones.

The old Universal Monsters seemingly had little value and were dumped into syndicated television for disposable viewing. How short-sighted. The TV airings drew massive audiences and helped the genre return to prominence. The release of Hammer’s Horror of Dracula (1958) and AIP’s I Was A Teenage Werewolf further resurrected the fading genre. Hammer reinvigorated fright features with full-color gothic horrors, while the black-and-white-centric AIP tapped into the teenage audiences.

The teenager-appealing elements resonated.

Before I Was a Teenage Werewolf, no horror movie featured adolescents in prominent roles. More importantly, the film focused on serious teenager laments, striking an emotional cord with its young, Rebel Without a Cause-loving audience.

Teenage Tony Rivers has problems. These troubles plagued him long before “regressing” into a werewolf. Tony struggles with anger management issues and becomes prone to fighting with little provocation. He’s not a “bad kid,” but he suffers from horrible depression after his mother’s passing. Tony Rivers’ is a “latchkey kid” who spends most of his time alone while his blue-collar father works double shifts to put food on the table.

When his anger gets the best of him at a party, he accidentally strikes his girlfriend, making him realize that his anger issues turned him into a figurative monster. He seeks help from an abusive hypnotherapist whose weird formula turns the lad into an actual werewolf.

Scores of teens who shared Tony Rivers’ angst flocked to see the film. They were primed to see such a melodramatic feature unfold. In many ways, I Was a Teenage Werewolf mimics a 1950s mental hygiene film teenagers saw in their classrooms, but one with added elements from the classic horror films the teens remembered from childhood re-releases.

Roll Out the 16mm Projector

“Mental hygiene” films are known by their other colloquial nickname, “classroom scare films.” The nicest name for the one or two-reel films was “social guidance films.” The glory days of classroom scare films ranged from the late 1940s to the late 1970s. When teachers broke out the 16mm projector, a short film with an important message about drug abuse, reckless driving, venereal disease, and other dangers played out via a projector’s bulb.

Coronet Films was a top producer of these direct-to-the-classroom short subjects, starting with the landmark Shy Guy film in 1947. Sid Davis was another producer/director of such one-reelers. Several of his shorts maintain a cult following to the present, including The Dangerous Stranger (1961, about child molesters) and Seduction of the Innocent (1961, about the slow descent into drug addiction.) Less salacious films produced over the years included How to Be Well-Groomed(1949) and Let’s Be Good Citizens at School (1954).

While some mental hygiene films often receive criticism and laughs for their over-the-top or reactionary approach to their subject matter, numerous films provide straightforward advice to teens about subjects they may not receive at home. Parents avoiding delicate topics stood back and allowed mental hygiene films to step in to do the job.

Outside of classroom scare films, very little media addressed the common problems and concerns young persons may face about their struggles. While 1950s television often portrayed an overly upbeat image of American family life, Hollywood sometimes swayed into controversial material with such projects as The Blackboard Jungle (1955) and the landmark Marlon Brando film The Wild One (1954).

Classroom mental hygiene films straddled the middle, sometimes succeeding in their presentations, sometimes delivering absurd results.

While I Was a Teenage Werewolf tapped into teen interest in the thrills associated with catching a wild horror film at the drive-in, the film also tapped into anxieties and nerves young persons often experienced and parents, teachers, the police, and politicians ignored.

In some ways, I Was a Teenage Werewolf offers cautionary insights about teenage behavior, including anger management issues and the inability to fit in with peers. Unlike a standard scare film, I Was a Teenage Werewolf has a cynical approach to trusting adults. It also featured a realistic protagonist who faced everyday problems that underscored the film’s dark fantasy elements.

Beastly Rages

Tony Rivers remains adrift, unable to cope with his mother’s passing and the stress of living in a single-parent household at a time when such arrangements were “less than” a traditional nuclear family setup.

Dr. Alfred Brandon unethically experiments on Tony because the young man’s fragile mental state makes him most susceptible to devolving into a violent, primitive state. Dr. Brandon suffers from “mad scientist disease.” He comes up with a crackpot plan to force humanity to behave better by starting the process of de-evolution back to savagery. (Good luck.)

Choosing the perfect test subject, a young man with a violent temper and psychological problems, also contributes to the disastrous outcome. Tony Rivers is a violent and angry man who starts a fight when a classmate gives him a friendly pat on the back or plays a prank. As a police officer warns, Tony will find himself in problems with the law or worse if he doesn’t get his act together.

The werewolf’s curse doesn’t turn an innocent man into a violent beast. The curse shifts the shape of a violent kid into something worse.

Hardly anyone would suggest the lycanthropes in Werewolf of London (1935), The Wolf Man (1942), and The Mad Monster (1942) were congenial. The high school-age wolf-monster of I Was a Teenage Werewolf is ferociously cruel. Previous were-creatures, including the similar science-based beast-man of The Werewolf (1956), stalked and hunted humans like an animal would seek prey. Tony Rivers’ werewolf is much different personality-wise because his werewolf has an underlying aggressiveness that comes through its snarling, salivating form.

Unlike his older compatriots, the teenage werewolf is exceptionally angry. And how is this surprising? Look how angry Tony Rivers behaves before he shifts into werewolf form. Those previous cinematic monsters suffered from a curse that turned them into a raging beast. Tony Rivers rages long before devolving into his beast persona.

Nothing supernatural drives the teenage werewolf. Angst is real and a curse found among younger earthbound humans. Doctor Brandon professed that the bestial rage reflects humans at their prime primeval worst.

And Tony Rivers’ werewolf shows its worst.

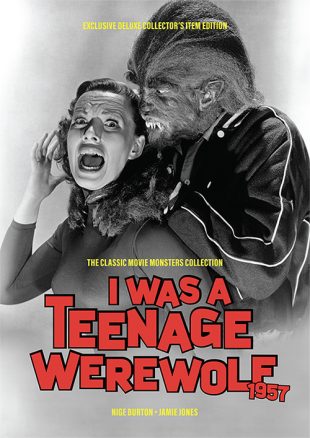

The most provocative and disturbing scene in the film is the brutal attack on the young gymnast. The young girl wears standard gymnast attire, making her provocatively underdressed for a 1950s film. Tony Rivers stands off to the side and watches her leeringly. While he does nothing to disturb the girl, he clearly enjoys watching the gymnast in her state of limited dress.

When the school bell rings and inexplicably forces Tony to change into the werewolf, there’s a disturbing element to his attack on the young woman. While killing her underneath a tarp helps cover up the violent death, it also creates a suggestive image.

Did the werewolf sexually assault the gymnast? While not overtly suggested, the hint exists.

The brutal assault is shocking but not surprising.

Tony Rivers becomes a vicious, savage animal when transformed into a werewolf. But was he not a vicious, savage human being before turning into a werewolf? While his past behavior never rose to murder and sexual assault, his angry rages contributed to repeated and escalating violence. Was he headed down a path of becoming a psychopath?

How much is fueled by the werewolf’s savagery vs. teen rage and angst? While nothing can calm a mindless werewolf, was there anything that could have contained Tony Rivers’ rage?

Without taking steps to deal with his troubled mental state, Tony Rivers could have graduated from accidentally hurting his girlfriend to becoming a deliberate abuser. Wisely, he seeks help, but he’s led to the wrong doctor.

The Mental Hygiene Angle

Unlike cult horror movies, mental hygiene films receive little praise. From a technical standpoint, little artistry went into these productions. The short subjects were shot as silent movies with a narrator track added to explain the proceedings – all to save costs. Often, they were overly melodramatic, simplistic, and, by today’s standard, woefully politically incorrect. True, several classroom hygiene films – particularly the ones made in the 1970s – were ridiculous.

That’s not to say that some classroom scare films sometimes don’t have a decent message. While a film telling teens to dress well and exhibit good manners may be excessively preachy, teens would benefit from dressing well and having good manners.

Good manners and behavior can go a long way when dealing with conflict. As Tony Rivers’ father says, “Sometimes, you just have to do it the other fella’s way.” Someone could make a short film about that philosophy.

If a director cut and re-edited a few scenes from the film, shot a little new footage, played the feature silently, and added a new voiceover narration, classroom audiences could see a mental hygiene film dubbed “The Other Fella’s Way.”

Tony Rivers doesn’t like doing things “the other fella’s way” because his anger issues translate into problems with peers and authority figures. An angry, dejected teenager won’t likely appreciate the advice to “go with the flow” and accept life’s crumbs. Anger yields conflict and rebellion, and Tony won’t listen to warnings. He doesn’t bend to acceptable norms of behavior, and his quick temper gets him into trouble.

The scene where Tony strikes his girlfriend serves as a major plot point – it results in Tony seeking help from Doctor Brandon, giving the film a happy ending.

Would it?

Only some classroom education films had upbeat conclusions, as a downbeat, tragic ending put the scare in a scare film.

I Was a Teenage Werewolf walks a thin line between a classroom scare film and a scary drive-in film. Comparing the AIP classic to a hypothetical mental hygiene film isn’t a stretch. Becoming a werewolf reflects the punishment Tony receives for not listening to the detective at the film’s beginning and not taking his father’s advice.

Still, the film has a subversive element that allows it to shift away from its mental hygiene elements. Listening to authority figures also results in Tony Rivers’ werewolf predicament.

De-Sanitizing Hygiene

Mental hygiene moralization falls victim to the artist’s curse. The artist paints the entire picture, controlling everything someone sees. If the artist wants to get a particular point across, anything contrary to that point never makes it to the canvas.

A mental hygiene film comes up with a conclusion and works backward. A teenager with good manners makes more friends, gets along with teachers and parents, and lives happily. That’s how the short film concludes, and everything proceeding reveals the disasters that bad manners bring forth and an inciting incident that leads to social behavioral changes.

While it would be hard to argue that continuing down a destructive path is a good idea, the overly bright world where peers and adults behave flawlessly doesn’t exist. However, characters act in such a way in a mental hygiene film to keep the focus on the central bad-mannered character and lead to the “moral of the story” ending.

I Was a Teenage Werewolf breaks from the moralistically idyllic mental hygiene conventions by showing adults aren’t always teenagers’ friends. Dr. Brandon does not have Tony Rivers’ welfare in mind when he injects him with the primordial werewolf formula. Nor does he care about anyone that Tony may harm in werewolf form. Dr. Brandon’s concerns lie with his selfish pursuits.

Moral thematics take a turn with Dr. Brandon’s actions. The “other fella’s way” isn’t always safe or sane, and even “upstanding” characters, such as trusted physicians, can be dangerous strangers.

The horror approach is not the only radical stylistic change that separates I Was a Teenage Werewolf from the prototypical mental hygiene film. Pure cynical realism hangs over the narrative, and the ending hardly presents a simplistic happy ending or one where “bad” kids or adults receive a one-note comeuppance.

As the detective says, after sending Tony Rivers, the Teenage Werewolf, to his demise, there was “No other way out. Nothing else we could do.”

Fantasy elements aside, I Was a Teenage Werewolf offers a stark moral lesson: like a ferocious wolf-monster, angst can consume its victims if they let it.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews