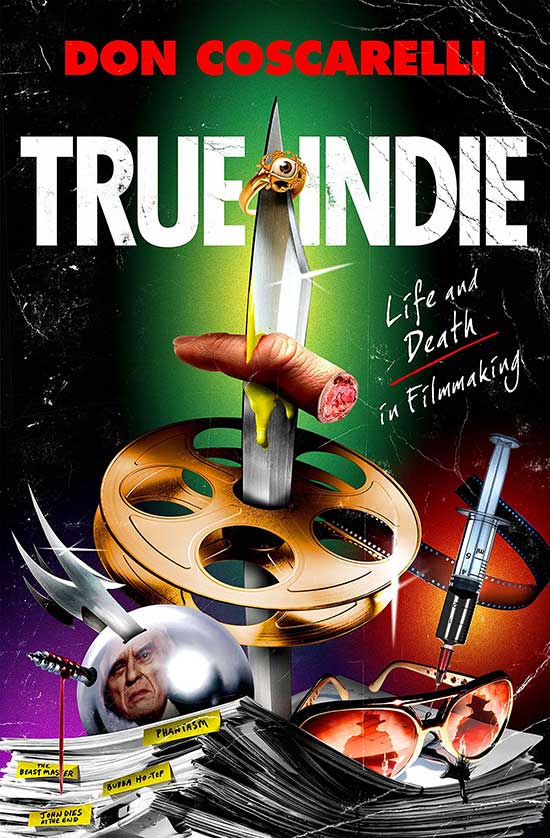

True Indie, the new memoir from Don Coscarelli—the man responsible for cult classics Phantasm, The Beastmaster, Bubba Ho Tep, and John Dies at the End—starts out with a bang, literally: the book’s prologue recounts the filming of his first car chase scene, for which the young director was so intent on getting the perfect shot that he ended up taking a shotgun blast straight to the face.

True Indie, the new memoir from Don Coscarelli—the man responsible for cult classics Phantasm, The Beastmaster, Bubba Ho Tep, and John Dies at the End—starts out with a bang, literally: the book’s prologue recounts the filming of his first car chase scene, for which the young director was so intent on getting the perfect shot that he ended up taking a shotgun blast straight to the face.

Coscarelli’s films have always been heavy on action—car chases and crashes, dangerous aerial maneuvers, explosions (“I am in love with Hollywood movie fireballs,” he writes, “I try to put one in every movie [whether necessary or not!]”), gnarly practical effects, and old-school physical stunts—so he’s able to keep up a propulsive tone throughout the book by recounting the complex logistics of, say, blowing up an entire house, as well as all manner of close-calls and near-catastrophes (such as the time one of his producers nearly died after jumping into the rapids of the deadly Kern River while attempting to rescue a young Catherine Keener, who he mistakenly thought to be drowning during an outdoor shoot). As he writes in the same opening chapter, “Indie filmmaking is damn hard…[it’s] like going to war.”

Like Robert Rodriguez’s canonical memoir about his beginnings as an independent film maker, Rebel without a Crew, True Indie is full of these types of juicy behind the scenes stories, but at heart, it is a guide for those who would seek to follow the same path, one that makes no bones about the harsh realities of the calling: “Every film is a start-up! And after we finish a film, the entire process, including the inherent risk, starts all over again.”

However, unlike Rodriguez’s book, subtitled Or How a 23-Year-Old Filmmaker with $7,000 Became a Hollywood Player, there’s no culminating Hollywood coronation. While every film he’s made since his 1979 horror breakout Phantasm has proven successful in the long run (save for 1988’s all-but-forgotten Survival Quest), Coscarelli has remained entirely independent throughout his life as a filmmaker.

Life is the key word here: after having his Call-to-Damascus moment while watching Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey as a child, Coscarelli started making his own movies in his stomping ground of Long Beach, California, recruiting his friends and classmates as his cast and crew. While still in high school, he and an early directing partner made a short-film that earned state-wide attention, as well as a TV commercial for their local YMCA.

From this, the pair brazenly transitioned directly into feature-filmmaking, shooting their script for the family drama Jim the World’s Greatest (1976), which would eventually be picked up by Universal Studios (earning Coscarelli, at the age of 18, the distinction of being the youngest director to ever have an office on the Universal lot). He would then branch out on his own with the boyhood comedy Kenny & Company (released the same year as his freshman film, 1976), which he sold to Fox Studios.

While neither film constituted a failure (both earned Coscarelli—as well as his father, who bankrolled the productions—a profit), they were each unceremoniously dumped into theaters, the studios responsible for their rollouts too busy with their upcoming major release—Jaws and Star Wars, respectively—to give a damn about these small, heartfelt, slice-of-life films.

Determined to make a film that would actually reach an audience, Coscarelli turned to horror. While sticking with the coming-of-age framework that he had used in his first two films, he came up with a dark fantasy about two orphaned brothers and their ice cream vendor friend, who happen upon a disturbing series of murders being committed by the local crypt keeper, an otherworldly figure known only as The Tall Man. Combining surrealist visuals, highly-imaginative special effects (including the now-iconic deadly flying silver spheres), and an emotional gut-punch of an ending, Phantasm became a smash hit, eventually cementing itself as one of the most beloved and influential American horror films of all-time.

Despite the film’s massive success, Coscarelli had to struggle to get each new movie made. True Indie goes into great detail for each one: from the frustrating, nearly cataclysmic disaster of The Beastmaster (which despite the interference of a lunatic producer spawned two sequels and a TV series), to the disappointment of Survival Quest, to the mixed bags of the Phantasm sequels (which, despite being well-received by fans, were given increasingly shabby releases, including the third and fourth entries going direct-to-video), to his comeback success with the Bruce Campbell starring horror-comedy Bubba Ho Tep, to his popular adaptation of David Wong’s genre (and mind) bending novel John Dies at the End.

Horror fans will find especially enticing the chapters that detail his initiation into the ‘Masters of Horror’ club (started by Mick Garris and featuring, among others, John Landis, Joe Dante, Tobe Hooper, John Carpenter, Larry Cohen, and Guillermo del Toro) that would spawn the beloved anthology series, for which Coscarelli’s Incident On and Off a Mountain Road would serve as the inaugural episode.

Throughout all of this, Coscarelli recounts the various collaborations and relationships that would help shape his career and personal life, most importantly those he’s shared with Phantasm stars Reggie Bannister, Michael Baldwin, and the late Angus Scrimm, to whom the he dedicates the book’s most moving chapters. Along the way, he also describes his various run-ins with all manner of Hollywood legends—from his fostering of nascent talents Roger Avery and Quentin Tarantino, to his amicable working relationship with notoriously difficult actor Rip Torn, to the missed-opportunity of having almost cast Brad Pitt in Phantasm 2 and the missed-catastrophe of having almost cast Gary Busey in Bubba Ho Tep.

Coscarelli’s writing style is casual and personable, and it’s a testament to his patience and sense of humor that he never comes off as bitter, even when detailing the heartbreak that comes hand-in-hand with indie filmmaking, a venture in which the bottom can fall out at any moment (as it did with scuttled projects such as the Roger Avery-scripted Phantasm 1999, or the Paul Giamatti-starring Bubba Nosferatu). Coscarelli doesn’t mince words about the current state of independent filmmaking either, which he thinks may well be “in its death throes.”

Despite his sobering outlook, Coscarelli’s memoir—like his larger career—is ultimately an inspirational one, made all the more inspirational by the fact that it doesn’t end in a shower of fame and fortune. It instead serves as a clear-eyed testament to the hard work of making movies at the independent level, told with all the verve, humor, and two-fisted action that have earned his films their devoted cult followings.

Review By zach vasquez

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews