SYNOPSIS:

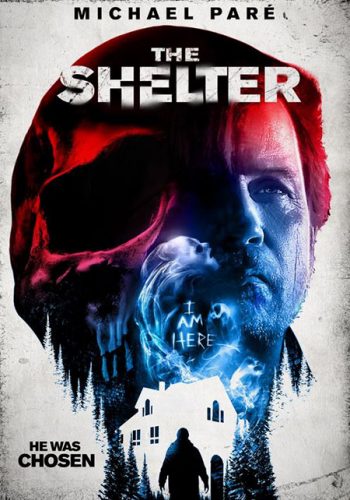

When Thomas, a grizzled and hard-drinking homeless man, lucks into an empty house, he thinks he’s got a warm bed and a hot bath ahead of him. What he doesn’t know is that the house isn’t as empty as he thinks it is.

REVIEW:

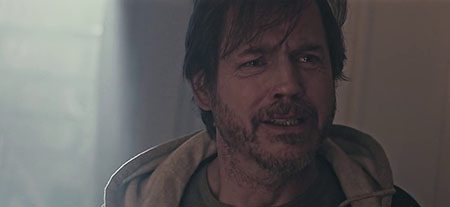

In 2015,’s movie The Shelter, journeyman actor Michael Paré stars as Thomas, a down and out drifter, in this 2015 horror film-cum-distended morality play. As razor to Paré’s bristle, we have Lauren Alexandra as Thomas’s wife, Josephine; Rachel Whittle as Thomas’s very close neighbor, Annie; and Daena Turner as Thomas’s daughter, Audrey. Reminiscent of a Rorschach test, or indicative of how a schizophrenic sees the world, the film jumps back and forth in time, from the past to the present to someplace else, going so far as to time-leap during dream sequences, then catapulting sidewise into some other realm, which might or might not be hell, all of this in a strenuous grasp for significance and pompous “deep structure”. Obviously, Director John Fallon shows no shame when it comes to grandiloquence.

Opening on a rather graphic sex scene between Thomas and Maggie (Amy Wickenheiser), an acquaintance of Thomas’s young enough to be his daughter, our character map and plot trajectory are laid out: Thomas has lost everything for some reason, has become a homeless drifter, and has few scruples when it comes to shacking and shaking with whomever will take him in. On this go round, Maggie is willing to shake but not shack; Thomas is asked to leave before her boyfriend, who’s the jealous type, gets back home. On the empathetic side, though, she tells him he take a bottle of scotch for the road. Out and about, he encounters more rejection, hostility, and a seemingly empty house that induces visions from his past, his present, and some depleted dreamland slowly degenerating into a nightmare.

Paré’s acting, as to be expected from a pro who’s been in the business for several decades, is quite polished, but not to the point of staleness; he gives unexpected turns and a nicely energetic portrayal of a proud but on the skids man looking for, you guessed it, shelter. Though partly due to the role, he does look as though he’s put in a few more miles than what he had back in his halcyon days of Eddie and the Cruisers. But this, too, is to be expected, considering everyone ages. This natural ripening is actually beneficial to where the character of Thomas is at this point in his life, so Paré’s maturity works here. Lauren Alexandra as Thomas’s wife and Amy Wickenheiser’s depiction of Thomas’s brief one-night stand are less refined but serviceable nonetheless.

Bobby Holbrook’s cinematography, on the other hand, seems to be playing on one note through the entirety of the movie; everything has the appearance of flatness, and the color is almost continually forced into a muted blue tonality in virtually every scene, from interiors to most exteriors, from night scenes to day scenes, from dreams to nightmares; the perpetually soft glow from ambient light filtering through frosted glass and misty fog diminishes badly needed depth in interiors and landscapes. Unfortunately, the lack of visual variety leaves the viewer with nothing to hold onto, no heft, and it brings on a worrisome boredom to Thomas’s struggle. The flavorless images aren’t helped by Director Fallon’s script, which may very well have called for such symbolizing of Thomas’s state of mind, but the disjointed theme is made even more ambiguous by the thin cinematography rather than clarifying it.

For a horror film, The Shelter isn’t very horrifying. It’s not very coherent, either; it focuses a lot on religious symbolism: crosses, crucifixes, Catholic cemeteries, a Catholic church, a mysterious Bible with blank pages, biblical quotes even begin and end the film. Other things happen in the movie that may or may not be of religious significance: the infinity symbol is present on a locked door in the house; whenever Thomas tries to light a cigarette, the lighter goes out, the name Thomas itself, as in doubting Thomas; Audrey appearing in Thomas’s nightmares telling him to ask for forgiveness so he can save himself.

All these things point to some Christian intent on the filmmaker’s part; what throws that association out the window is the amount of nudity and sex in many scenes, which leads one to assume, Fallon was only using the religious symbolism as a cheap attempt to add gravitas to a threadbare story. If you have to watch it, watch it only for Paré’s fine performance and leave the rest behind.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews