SYNOPSIS:

A young farmhand goes to war, leaving behind a pregnant girlfriend in an existential crisis.

REVIEW:

A young farmhand named Andre Demester gets called to war. He tells his friend, who bids him goodbye. He tells his girlfriend, who takes him on a walk that culminates in the two having sex in a frozen field. This seems to be her goodbye to him as well. The man makes it clear that he doesn’t desire an actual relationship, despite clearly having feelings for her, so the young woman goes off with another soon to be soldier. This leads to her characterization around town as a slut. She’s clearly distraught that the men around her are going to war, perhaps never to return, and she’s in tears. She doesn’t go with the wellwishers seeing them off, choosing to remain in the cold landscape of the farm.

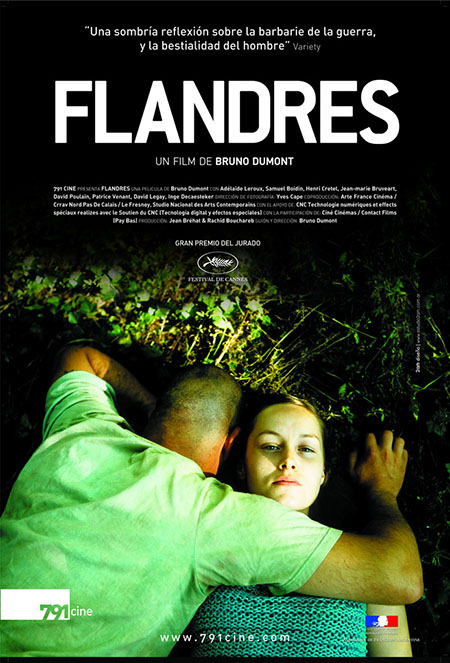

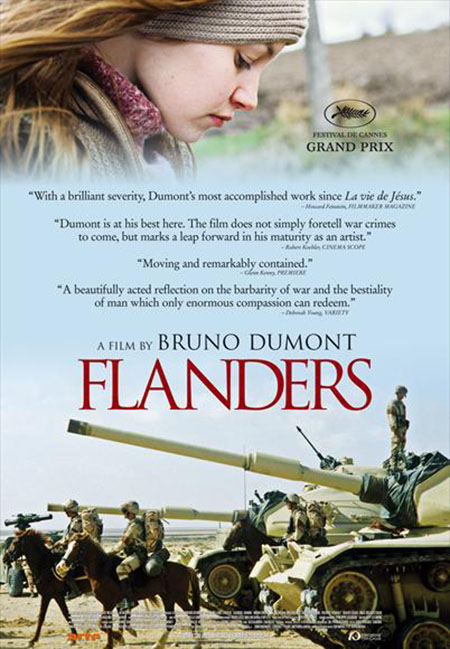

This is the backdrop for Bruno Dumont’s 2006 movie Flanders (Flandres), a story of the horrors and depression of every day life. The men travel from a frozen European city to a Middle Eastern desert, but the internal struggles remain the same no matter the location. It’s a bleak film, with settings as grey and colorless as the morality within. These are a group of people who believe that their outcomes are inevitable, and inevitably terrible. Everything is grey, snow, and mud, so why would the future for any of them be any brighter? They seek a better future at war, but all they find is the same horrific feelings they’ve internalized for so long. When their group of soldiers is attacked by mortar fire, blowing a young man to bits, they watch as a helicopter lands to take his body parts away on a stretcher, leaving the living soldiers in a war zone. The takeaway is clear: no one is leaving here alive, and while we know that some of the soldiers must surely live through this, we know that they will never be the same.

They immediately prove us correct. They fire on those who have fired on them, and soon realize that the “men” they have just killed are actually children. One is dead, and the other they leave to slowly bleed out. They rape a young woman who just happens to be there. They kill a man on a donkey for no reason other than the fog of war. And, when some of them receive their comeuppance, we can’t help but feel like they deserve it. What took them from being regular, everyday men to being stone cold killers and rapists? Is it really the war itself, the depravity that comes about when men are in a fight for their lives, or was it inside of them all along?

While this is never made clear, it is apparent that there is something inside these men that is broken. As we see their story paralleled with Barbe, the young woman left in France, we see that this brokenness is innate, not just a revelation of war. She is mentally disturbed, and when she finds that she’s pregnant (by who, we are unsure), she has a mental break down and is committed to a hospital. She is released in time to see Demester’s return, as he is the lone survivor of his group of warriors. She breaks down again, and he tells her he loves her, the realization that the actions committed by his group of soldiers will make him forever changed.

The horror in Flanders is existential. There are no monsters here but man. It’s the things we do to each other, in war and in peace, that make us terrible creatures. It’s the knowledge that everything will be the same tomorrow, and the recognition of how terrible this can truly be. For these men, war is just another mundanity of their lives. For the woman they leave behind, their absence is just another blow to her fragile psyche. After the war, after the horrors both seen and committed, Demester returns to Barbe and a life that remains the same. This is the horror that awaits: knowing that, through all of your experiences, both good and bad, there is no escape from the life that you live. And for some, this is as terrible a realization as any.

Dumont is a director’s director, giving us a movie that is at the same time visually boring and stunning. He gives us a view inside the human spirit, and we don’t always like what we see. Evil men get their terrible reward, except for when they don’t. There is nothing separating the “good” from the “bad,” and we are left hating all those who remain. Is there a better picture of the way life is for so many billions of people around the globe? That is what makes this film so truly horrifying: the realization that this is real life for so many, and the gratefulness that, for some of us, it isn’t. It’s a masterful film, and with a short runtime, one that should be seen by anyone who is interested in these Sundance-style films. It’s worth a watch for sure, as Dumont is a proven visionary. Well done, well acted, and fascinatingly bleak. Bravo.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews