SYNOPSIS:

A shadowy killer in black brutally murders fashion models.

REVIEW:

“Perhaps female beauty makes him lose his head and kill.”

In 1964, horror maestro Mario Bava, for better or worse, practically invented the cinematic giallo (a horror subgenre which harkened to Italian paperbacks released in the 1930’s which translated mystery novels and were characteristically yellow) and later, slasher genres (further reinforced by Bava’s own A Bay of Blood in 1971) with this film. At heart, Sei donne per l’assassino (or Six Women for the Murderer), is a murder mystery, but modern audiences will easily see the birth of future giallo tropes here. Following the unbridled success of Black Sunday and Black Sabbath (itself, arguably one of the greatest horror anthology films ever made), Bava was given a meager budget and expected to deliver a typical police procedural in the style of Edgar Wallace. Bava defied these expectations which, of course, resulted in the film failing both critically and at the box office.

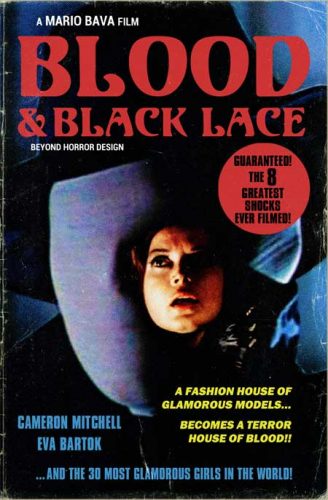

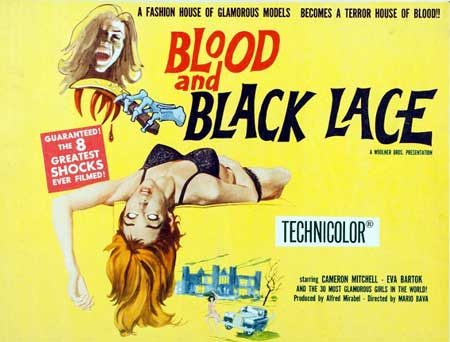

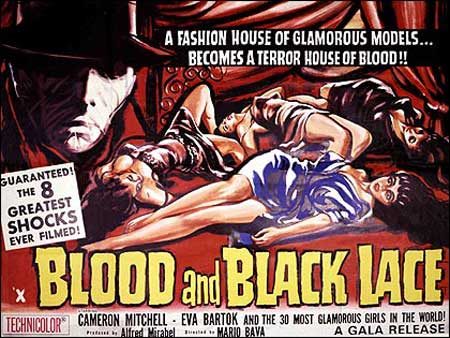

A fedora-wearing killer, complete with a featureless white mask and black trench coat, is murdering young models at the Marian fashion house for a diary which presumably contains the secrets of everyone employed there. The diary belongs to one of the models, Isabella, who is the first to meet a strangled fate. Manager, Max Marian (Cameron Mitchell), is, along with his lover and co-manager, the Countess Christina (Eva Bartok), rather detached, as are others who seem more concerned with the threat Isabella’s death represents than the death itself. Marco, tailor and general handyman, suffers from a severe nervous sensibility and harbors feelings for one of the models.

Outside of the fashion house, there are also suspects, such as Frank, antique dealer and cocaine addict who has questionable liaisons with some of the models. There is the Marquis Richard Morell (Franco Ressel) who borrowed a sizable sum from Isabella and never paid her back. Inspector Sylvester (Thomas Reiner) has the unenviable task of sifting through the detritus of evidence and the absurd list of suspects. The film does a decent job in keeping the audience off-balance, but who the killer is isn’t really the point. Just like the film itself, it is the gleefully macabre atmosphere and fashioning of the deaths of the six women that’s captivating.

Bava, purveyor of vibrant washes of colour and sculptor of fog, executes (no pun intended) the movement of his camera so effortlessly that even amidst some rather banal detective work one’s interest is irresistibly drawn to the screen. The set design is extravagant and the lighting is pure ecstasy (the Blu-ray is particularly breathtaking). Dario Argento and Martin Scorsese (to name only a couple) would’ve been lost without Bava’s pioneering zooms and breathtaking eye for composition. Every single scene is shot to stylish perfection as if the killer has a deeply rooted compulsion to murder his victims in the most lavish settings possible. There is certainly a misogynistic undercurrent running throughout the film which would persist in giallo and slasher films to follow, however, it also bears an ending which seems to suggest a kind of triumph by transcending to misanthropy. Right, Bava?

In addition, Carlo Rustichelli composed a brilliant score, particularly with a main theme titled, Atelier, echoing the prolific and world renown composer, Nino Rota and the films of Alfred Hitchcock (as a side note, if you’re watching the English-speaking version, practically all of the male voices are overdubbed by the Man of a Thousand Voices, Paul Frees – rather brilliant actually). Blood and Black Lace is a celebratory proto-giallo that, despite its many imitators, is still fresh and perilously glamorous.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews