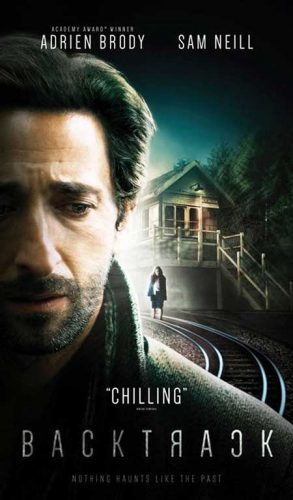

SYNOPSIS:

A troubled psychologist (Adrien Brody) returns to his hometown to uncover the truth behind his strange visions.

REVIEW:

Repressed memories are a thing, apparently. Some people swear by them the way other people swear by thorough colonics. The mind’s way of cleansing itself, I’m assuming. It sounds reasonable, if you don’t think too deeply about it. And like its ticklishly-close cousin, amnesia, it makes a convenient shibboleth for noirish expression, which has its own ticklishly-close cousin in horror. Or in this case, ghost stories.

Adrien Brody (he of the perpetually quizzical face) plays Peter Bower, a psychiatrist with issues of his own; putting a slight twist into the premise of Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense (1999), Bower has lost his child due to an automobile accident which may have been preventable if Bower hadn’t become distracted by a toy train display in a shop window. The loss leads to the requisite long faces and crumbling marriage, also reminiscent of Shyamalan’s masterpiece and all too prevalent in many ghost stories since. The film hops onto the slightly off-kilter bandwagon as Bower has sessions with patients who seem just enough out of place to be a tad creepy or simply a little delusional, which nicely sets up the is-it-all-in-his-head or is-he-being-haunted conundrum that runs through the rest of the movie.

All of this oddness eventually sends him back to his old school and discussions with his previous mentor, Duncan Stewart (Sam Neill), over concerns about the guilt — and the possible mental distortions arising from that guilt — he still experiences over his daughter’s death. Stewart’s main purpose in these scenes is to play the excavator. He asks Bower what distracted him at that shop window, what memory was the distraction bringing to the surface; in one scene, they examine a Pieter Bruegel painting which Bower has been dreaming about, Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap (the same painting eerily tracked through in the opening credits); Stewart says there’s always something just below the surface of Bruegel’s paintings which leads Bower to say the painting has always bothered him because he can’t see the trapper in the window, he can’t see his face.

Realizing he needs to find answers, Bower heads back to his hometown of False Creek, hoping it will dredge up those repressed memories and clear his conscience. Old acquaintances are revived, questions are asked, and investigations into the past are made, leading to a satisfactory, though not unexpected, conclusion.

Although this is Michael Petroni’s first attempt at directing horror, he shows a sophisticated affinity for the genre; his direction and writing are supple, producing a controlled, attenuated spookiness. The entire cast performs beautifully, especially Adrien Brody, who wonderfully plumbs the emotional depths required to make the film believable. The deep colors and lush cinematography of Stefan Duscio add the appropriate subtle dread to virtually every scene, creating a sustained unease throughout the length of the film. And the score, by Dale Cornelius, keeps the tone richly melancholic and moody.

Overall, Backtrack is high on well-executed chills, steady unrest, and intelligent story, while being low on adrenalin, cheap scares, and boorish antics. Though it lacks originality in minor ways, which includes an easily-anticipated denouement, it successfully makes up for these things with high-level craftsmanship, finesse, and an impish desire to unsettle.

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

![Mad Max bluray box[1]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Mad-Max-bluray-box1-238x165.jpg)