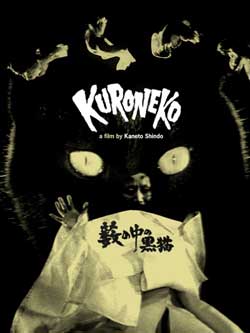

SYNOPSIS:

Two women are raped and killed by samurai soldiers. Soon they reappear as vengeful ghosts who seduce and brutally murder the passing samurai.

REVIEW:

“Fires everywhere in war, sparks fell even here.”

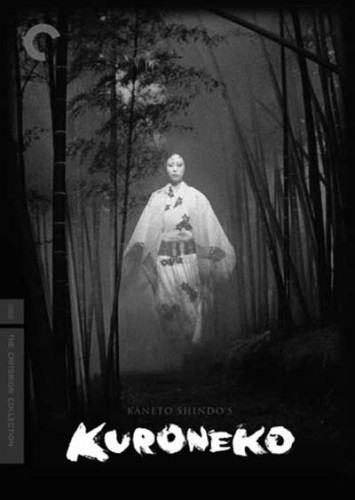

Kaneto Shindo is a filmmaker well-acquainted with ghostly folk tales (Onibaba, Akuto) but he has also made a career out of high drama (Children of Hiroshima, Sorrow is Only for Women, Ningen). Black Cat is a pensive combination of both camps. His horror, always thoughtful always deliberate, allows space to gather between moments of great dread. His approach is from a dynamic perspective; how one sequence leads to another, one scene prompting the next. The film is literally dark; an oppressive blackness pervades nearly every shot. Each character is surrounded by this indefinite space; a stifling miasma that is both felt and perceived.

Released in 1968, the film christens itself as a problematic unknown. In the midst of a civil war during the Heian period, a woman (Yone) and her daughter-in-law (Shige) are raped and murdered by a group of soldiers in Ezo. Their meager home, comfortably situated at the edge of a bamboo grove, is burned down in broad daylight. A black cat licks the wounds of their bodies as the militia ambles away. The women’s spirits become restless in that world and appear at the Rajomon Gate as ladies of refinement. In the night, samurai travel the roads and happen upon Yone who manipulates them into following her to the ashes of the fated house (now a hallucinatory mansion). The men die with tattered throats as the illusory mansion fades and they lie in the charred ruins or by the wayside drained of blood. Bodies accumulate and the governor takes notice.

Military hero and leader of the samurai, Raiko Minamoto, is ordered to secure the area of the shades but regards his superiors as spoiled politicians who reap the rewards of his dangerous toil. “Samurai means men who are proud of being strong warriors,” Reiko is reminded. He soon meets a young soldier who claims to bear the head of a fearsome enemy general, Kumasunehiko. The young man’s name is Hachi who was a farmer taken from his home and conscripted into battle. His dispatching of Kumaseunehiko is purely incidental and he gives a rousing account. Raiko rewards him with samurai status. Hachi happens to be Shige’s husband, the son of Yone. After his promotion, he returns to the house in the bamboo grove and is shocked to discover that only a clearing of ashes remain.

It’s not long before Raiko orders Hachi to resolve the paranormal quandary at Rajomon Gate. “You’ve won great distinction. Your valour is known all over the capital. Even beggars say you’re a strong samurai … the bravest man in the capital must act accordingly,” Raiko sweet-talks and cautions. Hachi rides off in the night, eventually stumbling upon Shige who leads him to a house resembling his own. It isn’t long before he realises that an evil spirit has taken the projection of his wife and mother. The apparitions disappear and he continues to seek them out.

Shige and Yone regret the demonic deal they made to enact their revenge, “Our vow is to kill samurai and suck their blood, so we invoked the evil gods. If only he were not a samurai…” Shige begins meeting him secretly and there are, of course, dire consequences.

Yabu no Naka no Kuroneko (“A Black Cat in a Bamboo Grove”) is graceful in its haunting gait. The classic tale of spectral revenge, it is a film of the early antiheroes of the written word and moving picture; spirits betrayed by fate, corrupted by fellow man. Amorality is denounced with biting condemnation as soldier after soldier dies, caught in a web of his own selfishness and greed. The soundtrack is spare but effective with erratic percussion and shrieking strings. Lyrical and mystically atmospheric in a way only Kabuki theatre can be, it is a siren’s tale of ethereal feminism and man’s insatiable need to destroy, even after death.

Rating: B

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews