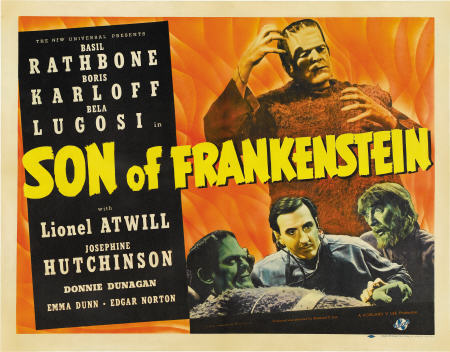

One of the first movies I remember seeing was Universal’s Son of Frankenstein, starring Karloff as the monster and Lugosi as Ygor. I’m not certain but, by juxtaposing the memory with others, my guess is that I was four years old. It was on Chiller Theater, a weekend late-show aired out of Pittsburgh. Watching the screen with eyes wide, I sat safe and snug on the couch with my dad, an aficionado of horror movies who was breaking me in early. We seldom missed Chiller Theater. It was like a ritual for us—every Saturday night after the news, host Chilly Billy haunted our home. In between the jokes and trivia (which, I think, were meant to provide an upbeat contrast to the usually less than upbeat film) and on-set promos for dry cleaning and tuxedo rentals, there was a horror movie which never failed to hold me spellbound.

While I remember little of that night’s movie as a whole, a scene which stands out in my mind is when Ygor ineffectually tries to move a passageway door made of stone, and the monster, without so much as grunting, shoves the slab aside. It was feats of strength such as this, I believe, which incited me the following day to pester my older cousin Sally to give me, with her makeup, a “Frankenstein face.”

As a kid, I didn’t merely pretend to be my heroes—I had to be in costume, as well. Some costumes were cheap or makeshift and some were mail-ordered or hand-tailored, but by the time I was eleven I’d dressed up as everything from Count Dracula to Spider-Man. Most of my in-costume imagining was limited to times when “play” was appropriate. But when things got a little too stressful in the real world, I found solace in knowing that, later, I could don my costume of choice and be master of my make-believe world.

Every character I pretended to be, it seems, had some sort off “power,” be it supernatural in origin, or secret knowledge, or just a really big gun. That Frankenstein’s monster was my first movie hero makes perfect sense. The creature had the most basic and elemental of powers—plain old, unadorned brute strength. For a boy stuck, like all four-year-olds, in a world full of giants, Frankenstein’s monster was ideal for emulation. With a grunt here and a growl there, all that was required was that I look menacing and walk as though I had just loaded my drawers. In return, I could swat aside, in my mind, all the big bad grown-ups who ever stood in my way.

Sometimes, though, I would develop a taste for arcana. In a kitchen “laboratory” I would pretend I was a Mad Scientist. Merging imagination with the real world, I was master of an alchemy which was usually part Jell-O gelatin, part baking soda, and part vinegar, or some similar unsavory concoction. Fortunately, Mr. Yuck and his mean green face told me what wasn’t safe to drink (yet apparently Mr. Yuck hasn’t tried a lime-Jell-O fizz), for the hero I imagined myself to be was that mad man of medicine, Dr. Henry Jekyll.

Again, underlying my reverie was a need for power. I was delighted at the thought of wimpy Dr. Jekyll transforming himself into the fearsome Mr. Hyde. I had seen the scenario in numerous versions of Stevenson’s classic yarn, but I was most taken by a comic-like version I had for my Show ‘n Tell, a machine which looked like a small TV with a phonograph on top. It was a sort of rear projection slide viewer which, on the screen, showed a series of images in sync with a record. Even though the Show ‘n Tell Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde couldn’t compare, aesthetically, to a motion picture, it offered one distinct advantage: I could see it any time I wanted, as often as I wanted. The same is true of my Show ‘n Tell version of Gulliver’s Travels. Though I didn’t know a thing about Swift’s political implications, I knew that Gulliver was big where he was, and he could kick butt if he wanted to.

It was around this same time—between seven and eight years of age—that I saw the Spider-Man cartoon program. And I became obsessed. Here was a super hero who had brute strength, but relied as much on his wits (he created his own “web-shooter” out of a home chemistry set). He was easy to identify with, because along with being a crime-fighting badass he was also (when out of costume) nerdy Peter Parker.

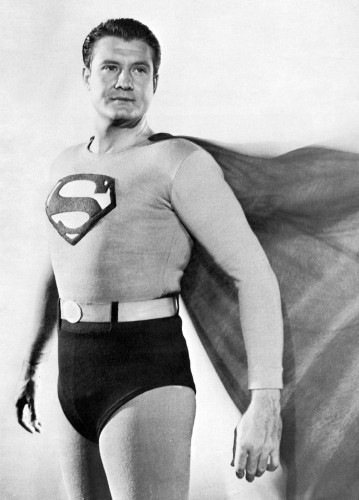

Unlike Superman, that paragon of probity, Spider-Man initially had no aspirations of being a crime fighter. After gaining his powers, his original plan was to use them to become a movie star. A night-prowling burglar, however, murdered his uncle, giving Peter Parker vengeance as a motive.

Though innocence incarnate, children can seldom live up to the unremitting righteousness of Superman. And they know it—aren’t they sometimes told by parents (and sometimes too often) that they’re “bad”? It is true that kids often revel in seeing the villains in action, but they also need to see their values (or perhaps their parents’ values) reinforced, as well as their notions of justice. So, they can’t quite root for the bad guy, yet perfect good guys make kids feel as though they can’t live up. Superman may not be perfect—he’s vulnerable to Kryptonite and can’t see through lead—but he’s substantively the super hero equivalent of Mary Poppins.

For me, Spider-Man was appealing because he sometimes got pissed off, made mistakes, got hurt, and was occasionally self-serving. I needed to feel that I didn’t have to be perfect to be powerful. Spider-Man served that purpose. I had a Spider-man costume, of course, and action figures with which I facilitated my fantasies. Among my other paraphernalia were a Spidey lunch-box, Spidey pajamas, and even Spidey sheets. In other words, I ate and slept Spider-man.

At around age ten, though, my Spider-man fixation gave way to Dirty Harry Callahan. Brandishing his big bore .44—which he boasted was “the most powerful handgun in the world”—Dirty Harry was a good guy with a bad attitude. He took crap from no one. Looking back, I can see now that my change of heroes wasn’t merely a forsaking of preternatural power for the more pragmatic; I was coping with certain fears, battling them unconsciously.

From as far back as I can remember, I had a fear of people to whom my grandmother indiscriminately referred as “hippies.” The term, as I came to know it, had connotations which went beyond associations with “flower children” and tambourines and psychedelic paintings. To me, hippie was a frightening word. It meant bad people who smoked dope, had long hair, and would kill you if you made them mad.

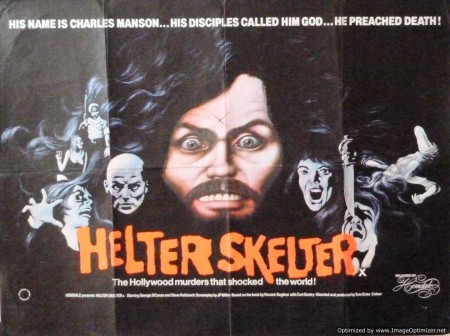

My concept of “hippie” was not symbolized in my mind by any one image or picture (though, ironically, I sometimes affiliated the concept with the “peace” finger-sign), nor could it be described with any one word or phrase. Born in 1968, I missed the turmoil of that decade, but in the early seventies a lot of scary things were gong on. I remember my grandparents talking about “those hippies out in California” who murdered some people in their home. Later, I watched Helter Skelter, a made-for-TV movie that was “based on the true story.” It was about “those hippie murders,” as my grandmother said.

A year or so later, at a drive-in theater with my dad, I saw a movie called The House by the Lake, in which a group of drunken, greasy-looking hoods follow a couple home and terrorize them. To me, their actions bore an unnerving resemblance to those done in Helter Skelter. And the hoods in The House by the Lake looked an awful lot like the bikers my grandmother sometimes pointed at out the car window, while uttering her all-purpose appellation—”hippie.”

Somewhere in the period between Helter Skelter and that night at the drive-in, someone shot at our house. The bullet shattered the picture window and lodged in the furthermost wall at the opposite end of the house. At the time, my dad was working as an undercover narcotics officer for the Sheriffs Department. The people he arrested, I was told, were “dope-heads.” Dope-heads, of course, were hippies. And when I learned that the person who shot up our house was someone my dad had arrested, a terrifying realization occurred to me: the hippies had tried to shoot us. Like the people in the movies, we weren’t even safe in our own home.

When I saw Dirty Harry on TV for the first time it instantly became my favorite movie (with Death Wish as a close runner up). I now had a new hero. Though I did not realize it at the time, the bad-guy in the film—dubbed the “Scorpio killer”—somehow fit my concept of “hippie.” And what did the bad-guy do in the film? He shot people in their homes, sniper-style. (I’ll never forget the opening scene in which the girl is shot while swimming in her pool.) To my young mind, Dirty Harry was the Kit Carson of crime—instead of hunting Indians, Dirty Harry went after those bad ol’ hippies.

At around age eleven I went from having a two-dimensional good-guy as my hero back to having what was essentially a one-dimensional villain. After watching Christopher Lee bare his fangs in one of the Hammer horror flicks, my new hero was Dracula. Looked at from a Freudian perspective, it seems I had “regressed” from a phallic form of aggression—Dirty Harry’s perilous pistol—to an oral form—Dracula’s conical canines. Regression, say the Freudians, is a “defense mechanism,” which is used by the unconscious to protect the conscious from anxiety. If this is true, then in retrospect it’s clear what my anxiety was.

About a month after I turned eleven, my dad shot someone. It wasn’t job related, as he had given up police work. It was simply the result of a fit of rage. Our family went through a year of hell, but in the end things turned out well, at least in comparison to how things could have turned out. Needless to say, though, in the interim I lost all interest in Dirty Harry Callahan. I didn’t want to think about guns. But I needed, more than ever before, to feel as though I had power over my world. Dracula served that purpose.

During the time my dad was away, serving a six-month sentence, I used to get comfort from watching horror films, especially the Hammer Dracula films—my dad’s favorites. I was reminded of a time when I felt safe and snug on the couch, watching Chiller Theater with my dad.

Throughout my life I’ve alternated between preferences for certain film genres. Mostly I like horror movies. They remind me of a time when I felt secure. And by watching a monster that I know can’t exist (in spite of whatever verisimilitude may have been achieved) I project onto the screen—and thus am purged of—my free-floating fears. But when my fears are more definite, and I need a more lifelike model of power, I turn to violent action-adventure films. Oftentimes my fears, on these occasions, are social in origin. Once again I need a hero to stop those bad ol’ hippies.

Perhaps that’s why I so delighted, recently, in re-experiencing Howard Hawks’ The Thing. What is the Thing but a “hippie” from outer space? I know now that all those times I followed my grandmother’s pointing finger, what I really saw was nonconformity.

Though nonconformity wasn’t in my vocabulary, the connotations were nonetheless negative. The hippies were the dope-heads and the bikers, those who looked weird and wore weird clothes. The Thing, then, is the epitome of nonconformity. It certainly looks weird enough. And instead of doing dope, it gets its fix drinking blood.

Unlike Frankenstein’s monster (to whom the Thing bares a strong resemblance), there is little about the Thing which evokes sympathy, and certainly not empathy. And though both the Thing and Dracula drink blood, the former lacks the charm and grace of the latter.

The Thing is pure “hippie,” according to my childhood definition of the word. And sometimes, as an adult, I can’t help feeling as though I were surrounded by “hippies.” It takes a Dirty Harry or, in the case of The Thing, a Captain Hendry to purge me of my social angst. Once purged, I can then return to my favorite film genre—horror—and recapture the familiar, safe feelings of childhood.

Frankenstein, My Old Man, and the Hippies

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews