“Sometime in the future, the city of Metropolis is home to a Utopian society where its wealthy residents live a carefree life. One of those is Freder Fredersen. One day, he spots a beautiful woman with a group of children, she and the children who quickly disappear. Trying to follow her, he, oblivious to such, is horrified to find an underground world of workers, apparently who run the machinery which keeps the above ground Utopian world functioning. One of the few people above ground who knows about the world below is Freder’s father, Joh Fredersen, who is the founder and master of Metropolis. Freder learns that the woman is Maria, who espouses the need to join the ‘hands’ – the workers – to the ‘head’ – those in power above – by a mediator or the ‘heart’. Freder wants to help the plight of the workers in the want for a better life. But when Joh learns of what Maria is espousing and that Freder is joining their cause, Joh, with the assistance of an old colleague and now nemesis named Rotwang, an inventor, works toward quashing a supposed uprising, with Maria as the center of their plan. However, Joh is unaware that Rotwang has his own agenda. But if any of these plans includes the shut down of the machines, total anarchy could break loose both above ground and below.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

The idea of progress itself produced a major line of development in genre cinema. If the Gothic strand represents the monsters of darkness erupting into the sunlight, then the science fiction strand represents the future. But filmmakers were not generally prepared to accept the Utopian elements in science fiction – the idea that that the world could be a better place through progress – and the First World War, where death on an unparalleled scale had been unleashed, partly through new technologies, knocked much of the optimism out of projections of the future. The image of the machine that would save us had metamorphosed into the image of the machine that would enslave us.

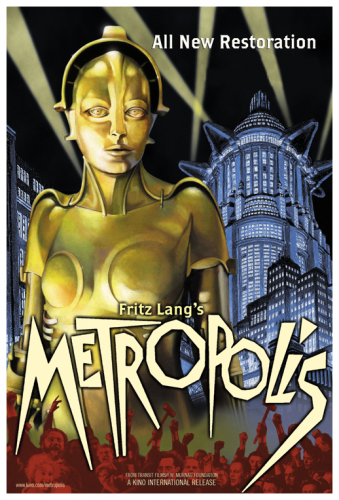

The first great science fiction film is still regarded as one of the very greatest films ever made: Fritz Lang‘s Metropolis (1927). Some few earlier films, notably the Russian Aelita (1924) had sequences set in the future, but there had been nothing so full-blooded as Metropolis, the archetypal film of the future. Lang was already one of the most important figures in genre cinema. A friend of Robert Wiene, he had worked on the script of The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari (1919), then he made the extraordinary Doctor Mabuse (1922), and followed through with the epic two-parter Die Nibelungen: Siegfried (1923) and Kriemhild’s Revenge (1924) are amongst the most spectacular fantasy adventures ever made.

The first great science fiction film is still regarded as one of the very greatest films ever made: Fritz Lang‘s Metropolis (1927). Some few earlier films, notably the Russian Aelita (1924) had sequences set in the future, but there had been nothing so full-blooded as Metropolis, the archetypal film of the future. Lang was already one of the most important figures in genre cinema. A friend of Robert Wiene, he had worked on the script of The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari (1919), then he made the extraordinary Doctor Mabuse (1922), and followed through with the epic two-parter Die Nibelungen: Siegfried (1923) and Kriemhild’s Revenge (1924) are amongst the most spectacular fantasy adventures ever made.

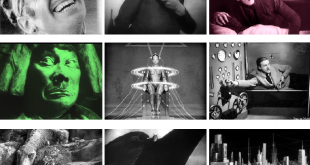

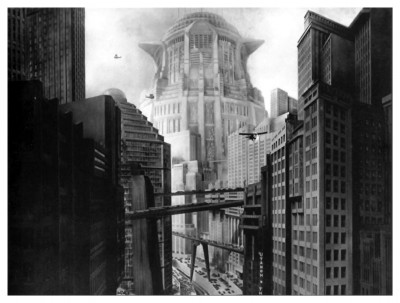

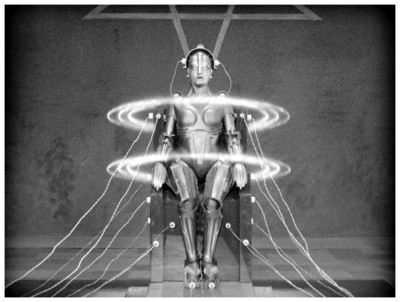

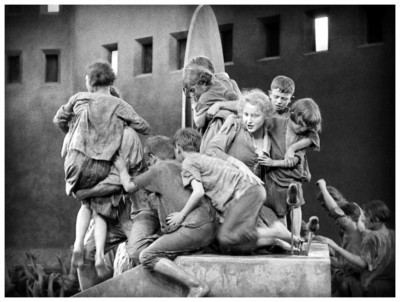

It’s Fritz Lang’s sheer commitment to the science fiction aspects of the film that makes Metropolis so startling even today. The future is evoked not only in gigantic cityscapes but in tiny details, whereas even today many films set in the future are content with one or two futuristic elements in an otherwise contemporary-seeming story. The love story at the heart of Metropolis has perhaps lost its power to enthrall, but the visual imagery remains archetypal: The shuffling workers in the underground city; the soaring towers of the upper city; the robot duplicate of Maria created by the mad scientist Rotwang to deceive her upper-class lover; the thirty thousand extras used in the crowd scenes; the great disaster spectacle of the lower-city flood.

It’s Fritz Lang’s sheer commitment to the science fiction aspects of the film that makes Metropolis so startling even today. The future is evoked not only in gigantic cityscapes but in tiny details, whereas even today many films set in the future are content with one or two futuristic elements in an otherwise contemporary-seeming story. The love story at the heart of Metropolis has perhaps lost its power to enthrall, but the visual imagery remains archetypal: The shuffling workers in the underground city; the soaring towers of the upper city; the robot duplicate of Maria created by the mad scientist Rotwang to deceive her upper-class lover; the thirty thousand extras used in the crowd scenes; the great disaster spectacle of the lower-city flood.

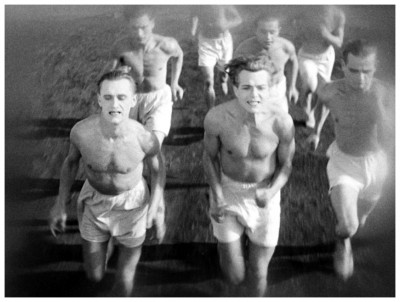

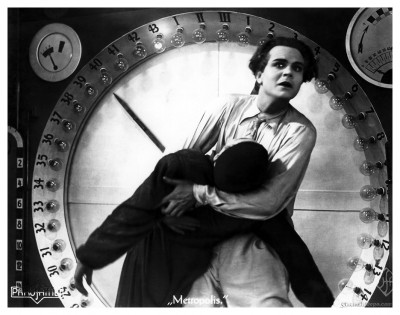

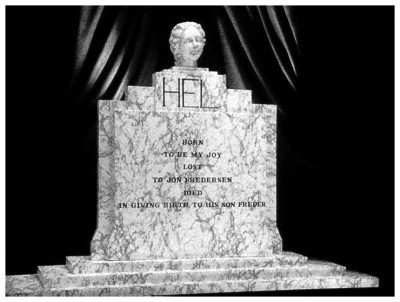

The action is set in a vast city of the future neatly divided into the downtrodden masses and the ruling elite. A member of the latter is a young man named Freder Frederson (Gustav Frohlich), who is son of the master of Metropolis, Joh Frederson (Alfred Abel). Freder, who spends most of his time running around in outsized white knickerbockers having fun with his friends, doesn’t know of the worker’s existence until he encounters a beautiful girl named Maria (Brigette Helm) who comes from ‘down below’. He tries to follow her when she returns below, and finds himself in a nightmarish world where men work unceasingly to tend vast machines and themselves are reduced to mere human cogs within the city’s mechanical bowels. Freder is horrified by what he sees but persuades a worker to change clothes with him so he can continue his search for Maria. Eventually he finds her in a makeshift church beneath the city where she is preaching on the subject of good working relationships.

The action is set in a vast city of the future neatly divided into the downtrodden masses and the ruling elite. A member of the latter is a young man named Freder Frederson (Gustav Frohlich), who is son of the master of Metropolis, Joh Frederson (Alfred Abel). Freder, who spends most of his time running around in outsized white knickerbockers having fun with his friends, doesn’t know of the worker’s existence until he encounters a beautiful girl named Maria (Brigette Helm) who comes from ‘down below’. He tries to follow her when she returns below, and finds himself in a nightmarish world where men work unceasingly to tend vast machines and themselves are reduced to mere human cogs within the city’s mechanical bowels. Freder is horrified by what he sees but persuades a worker to change clothes with him so he can continue his search for Maria. Eventually he finds her in a makeshift church beneath the city where she is preaching on the subject of good working relationships.

The basis of her message seems to be that the two parties should at least meet and discuss the situation now and then. Hardly revolutionary, but upsetting enough to Joh Frederson who is spying on the meeting. Frederson then instructs a mad scientist named Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) to construct a robot double of Maria, and they test out her effectiveness at the Yoshiwara nightclub where, scantily clad, she performs an extremely erotic dance. The test proves successful – not a bolt shows through her human disguise – and the male patrons are quickly driven into a frenzy of lust. Then, in the clothes of the saintly Maria, she leads the workers in a violent revolt which results in the wreaking of the city’s machinery. Meanwhile, the real Maria who has been imprisoned by Rotwang, manages to escape just in time to rescue the children of the workers from a flood caused by the wrecked machinery.

The basis of her message seems to be that the two parties should at least meet and discuss the situation now and then. Hardly revolutionary, but upsetting enough to Joh Frederson who is spying on the meeting. Frederson then instructs a mad scientist named Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) to construct a robot double of Maria, and they test out her effectiveness at the Yoshiwara nightclub where, scantily clad, she performs an extremely erotic dance. The test proves successful – not a bolt shows through her human disguise – and the male patrons are quickly driven into a frenzy of lust. Then, in the clothes of the saintly Maria, she leads the workers in a violent revolt which results in the wreaking of the city’s machinery. Meanwhile, the real Maria who has been imprisoned by Rotwang, manages to escape just in time to rescue the children of the workers from a flood caused by the wrecked machinery.

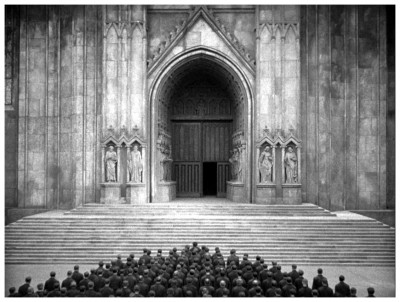

The workers, believing that their children have been drowned, attack the robot Maria and burn her at the stake. While the robot is burning, someone in the crowd notices that on top of the nearby cathedral another Maria is being pursued by the sinister Rotwang. Freder immediately dashes off to rescue her and the crowd, including Joh Frederson, watch in horror as the drama high above them unfolds. But all ends happily for everyone except crazy old Rotwang who falls to his death, Freder brings Maria safely down to the ground and persuades his father to be nicer to his workers. The film closes with a shot of Joh Frederson unenthusiastically shaking hands with supervisor Grot (Heinrich George) while the workers look on approvingly, no doubt forgetting that they will have to work 24/7 for the next ten years to repair all the damage.

The workers, believing that their children have been drowned, attack the robot Maria and burn her at the stake. While the robot is burning, someone in the crowd notices that on top of the nearby cathedral another Maria is being pursued by the sinister Rotwang. Freder immediately dashes off to rescue her and the crowd, including Joh Frederson, watch in horror as the drama high above them unfolds. But all ends happily for everyone except crazy old Rotwang who falls to his death, Freder brings Maria safely down to the ground and persuades his father to be nicer to his workers. The film closes with a shot of Joh Frederson unenthusiastically shaking hands with supervisor Grot (Heinrich George) while the workers look on approvingly, no doubt forgetting that they will have to work 24/7 for the next ten years to repair all the damage.

The main absurdity in the story is the absence of any reason why the master of Metropolis should want to cause a revolution that would destroy his city. The plot and action of the film are really on the level of a fairy-tale, which makes the contrast with its powerful imagery all the greater. Though supposedly set in the future, there is little that is truly futuristic about the city – the New York skyline of the time would have seemed more modern. For all its skyscrapers and personal aircraft that can’t tilt their wings, Metropolis is a purely Gothic city. Most of the scientists in early cinema were portrayed as mere magicians in modern disguise but, in Metropolis, there is no attempt to disguise Rotwang’s magical nature. Rotwang is definitively a sorcerer of the old school who lives in a bizarre house decorated with pentagrams and, although he builds a robot, he uses magic to transform the stiff metallic figure into the smooth and supple doppelganger of Maria.

The main absurdity in the story is the absence of any reason why the master of Metropolis should want to cause a revolution that would destroy his city. The plot and action of the film are really on the level of a fairy-tale, which makes the contrast with its powerful imagery all the greater. Though supposedly set in the future, there is little that is truly futuristic about the city – the New York skyline of the time would have seemed more modern. For all its skyscrapers and personal aircraft that can’t tilt their wings, Metropolis is a purely Gothic city. Most of the scientists in early cinema were portrayed as mere magicians in modern disguise but, in Metropolis, there is no attempt to disguise Rotwang’s magical nature. Rotwang is definitively a sorcerer of the old school who lives in a bizarre house decorated with pentagrams and, although he builds a robot, he uses magic to transform the stiff metallic figure into the smooth and supple doppelganger of Maria.

The main creative force behind Metropolis was Fritz Lang’s Though he originally trained as an architect, he soon became a graphic artist and, for a time, supported himself by selling cartoons and caricatures. As a result of wounds sustained during World War One, he turned to writing and began selling melodramatic thrillers. Then he entered the film industry and started to make films on similar subjects. One of the first was The Spiders aka Die Spinnen (1919) about a group of men who attempt to take over the world using Inca gold, and later made the first of the famous Doctor Mabuse (1922) films about an evil genius who also plans world conquest. In fact, many of his silent films contained science fiction or fantasy elements. When the Nazis came to power Lang was offered the headship of the Nationalist-Socialist film industry by Joseph Goebbels, who told him that Adolf Hitler had been enormously impressed by Metropolis. Lang, however, like many other filmmakers in Germany, left the country and, after a spell in France, emigrated to America where he continued to make films.

The main creative force behind Metropolis was Fritz Lang’s Though he originally trained as an architect, he soon became a graphic artist and, for a time, supported himself by selling cartoons and caricatures. As a result of wounds sustained during World War One, he turned to writing and began selling melodramatic thrillers. Then he entered the film industry and started to make films on similar subjects. One of the first was The Spiders aka Die Spinnen (1919) about a group of men who attempt to take over the world using Inca gold, and later made the first of the famous Doctor Mabuse (1922) films about an evil genius who also plans world conquest. In fact, many of his silent films contained science fiction or fantasy elements. When the Nazis came to power Lang was offered the headship of the Nationalist-Socialist film industry by Joseph Goebbels, who told him that Adolf Hitler had been enormously impressed by Metropolis. Lang, however, like many other filmmakers in Germany, left the country and, after a spell in France, emigrated to America where he continued to make films.

Edgar G. Ulmer is another German director who later worked in America and had been Lang’s assistant on many of his German films including Metropolis, Die Nibelungen, Spione (1927) and M (1932): “At that time, up to the coming of sound, there were two directors in each picture – a director for the dramatic action and for the actors, and then the director for the picture itself who established the camera angles, camera movements, etc. There had to be teamwork. Our sets were built in perspective with rising or sloping floors. Everything was constructed through the viewfinder. So what happened was you could only take one shot in that set if you had a room. If there were ten shots of it, you built ten sets of that one room. Because the one eye was the point of the perspective, the furniture was built in perspective. That’s where the great visual flair of the pictures came from. It gave you, of course, a completely controlled style. When you look at the old UFA pictures today, you’re startled at how precise every shot is. Because a set was built for each one.”

Edgar G. Ulmer is another German director who later worked in America and had been Lang’s assistant on many of his German films including Metropolis, Die Nibelungen, Spione (1927) and M (1932): “At that time, up to the coming of sound, there were two directors in each picture – a director for the dramatic action and for the actors, and then the director for the picture itself who established the camera angles, camera movements, etc. There had to be teamwork. Our sets were built in perspective with rising or sloping floors. Everything was constructed through the viewfinder. So what happened was you could only take one shot in that set if you had a room. If there were ten shots of it, you built ten sets of that one room. Because the one eye was the point of the perspective, the furniture was built in perspective. That’s where the great visual flair of the pictures came from. It gave you, of course, a completely controlled style. When you look at the old UFA pictures today, you’re startled at how precise every shot is. Because a set was built for each one.”

Born in Vienna in 1900, by the early twenties Edgar G. Ulmer was working as an assistant to master director F.W. Murnau, whose horror tour-de-force Nosferatu (1922) I discussed recently. In 1929 he and Robert Siodmak co-directed the acclaimed semi-documentary People On Sunday (1929), an awfully boring topic, even for a documentary. Also in the crew of that film was Billy Wilder and Fred Zimmerman. Come the rise of the Nazis, Siodmak, Wilder and Zimmerman all emigrated to Hollywood and found work with major studios, over the years turning out superb films like The Spiral Staircase (1945), Double Indemnity (1944), Sunset Boulevard (1950), High Noon (1952), From Here To Eternity (1953) and A Man For All Seasons (1966). Ulmer only worked once for a major studio – Universal – and the result was the horror gem The Black Cat (1935) starring Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi.

Born in Vienna in 1900, by the early twenties Edgar G. Ulmer was working as an assistant to master director F.W. Murnau, whose horror tour-de-force Nosferatu (1922) I discussed recently. In 1929 he and Robert Siodmak co-directed the acclaimed semi-documentary People On Sunday (1929), an awfully boring topic, even for a documentary. Also in the crew of that film was Billy Wilder and Fred Zimmerman. Come the rise of the Nazis, Siodmak, Wilder and Zimmerman all emigrated to Hollywood and found work with major studios, over the years turning out superb films like The Spiral Staircase (1945), Double Indemnity (1944), Sunset Boulevard (1950), High Noon (1952), From Here To Eternity (1953) and A Man For All Seasons (1966). Ulmer only worked once for a major studio – Universal – and the result was the horror gem The Black Cat (1935) starring Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi.

“Fritz Lang was a designer too, he designed advertising posters when he came to Berlin. Lang had an unbelievable energy and stick-to-itiveness – you could never stop him. He saw what he wanted in the picture, nothing could distract him, he would do it fifty times.” Ulmer, however, did not get on well with Lang. “Not at all because, on the set, he was the incarnation of the Austrian who became the Prussian general. A sadist of the worst order you can imagine. He was a great picture-maker who fortunately married the best scenario writer in Germany, Thea von Harbou.” Harbou, who wrote Metropolis, collaborated with Lang on a number of his films, including Woman On The Moon (1929) and M.

“Fritz Lang was a designer too, he designed advertising posters when he came to Berlin. Lang had an unbelievable energy and stick-to-itiveness – you could never stop him. He saw what he wanted in the picture, nothing could distract him, he would do it fifty times.” Ulmer, however, did not get on well with Lang. “Not at all because, on the set, he was the incarnation of the Austrian who became the Prussian general. A sadist of the worst order you can imagine. He was a great picture-maker who fortunately married the best scenario writer in Germany, Thea von Harbou.” Harbou, who wrote Metropolis, collaborated with Lang on a number of his films, including Woman On The Moon (1929) and M.

Metropolis created visual equivalents for many of the great ideas of science fiction: Mankind dwarfed by inexorably working machinery and subjugated to it, and the contrasts between the world of feeling and the world of technological progress – cold, powerful and rational. Practically every science fiction film made ever since owes a debt to Metropolis. And it’s with that thought in mind I’ll bid you farewell, but not before thanking King Of The Bs by Charles Flynn and Tod McCarthy (published 1975) for assisting my research for this article, and invite you to please join me again next week as we see what the postman leaves on my doorstep – and sets on fire – for…Horror News! Toodles!

Metropolis created visual equivalents for many of the great ideas of science fiction: Mankind dwarfed by inexorably working machinery and subjugated to it, and the contrasts between the world of feeling and the world of technological progress – cold, powerful and rational. Practically every science fiction film made ever since owes a debt to Metropolis. And it’s with that thought in mind I’ll bid you farewell, but not before thanking King Of The Bs by Charles Flynn and Tod McCarthy (published 1975) for assisting my research for this article, and invite you to please join me again next week as we see what the postman leaves on my doorstep – and sets on fire – for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews