SYNOPSIS:

“The poet Orphée is popular among the general public but detested by the avant-garde at the Café des Poètes. A young poet is killed by two motorbikes just outside the café. His patroness, called the Princess, brings the body to her car, and asks Orphée to come along as a witness. From the car radio a monotonous voice is reciting meaningless lines, which Orphée conceives as the fresh inspiration he has been looking for to renew his writing. In a deserted house he witnesses how the Princess revives the dead poet and disappears with him into a mirror. The chauffeur Heurtebise takes Orphée back home, where Eurydice is longing to tell him that she is pregnant. Orphée ignores her, and sneaks out to the garage, to listen to the captivating voice in the car radio. When Eurydice leaves the house, the two motorbikes kill her on the road. Heurtebise shows the remorseful Orphée how to follow Eurydice through a mirror. When Orphée finds Eurydice in the other world, a court allows them to return to life under the condition that he never looks at her. Orphée is tormented by conflicting feelings, because he is also in love with the Princess, his personal Death.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Jean Cocteau was more like a phenomenon than a mere artist, and his talents read like the sort of list Narcissus would have drawn up for himself had he ever bothered to put stylus to wax tablet. Cocteau thought of himself predominantly as a poet, however, and this view permeated his films and allowed him the freedom to invent. But, during the early forties, there were many problems making movies in France under the German occupation and French cinema began exploring the world of fantasy without any hope for the future. For example The Eternal Return (1943), written by Cocteau, is a retelling of the legend of Tristan and Isolde in modern dress. The Eternal Return now seems like a five-finger exercise, made to prepare Cocteau for his own two great fantasy films of the post-war years. Beauty And The Beast (1946) is the most famous of his dream fantasies, closely followed by Orpheus (1950), a film which cannot fail to move viewers when seen for the first time and at a young enough age, and provide them with some understanding of the imaginative possibilities of the cinema.

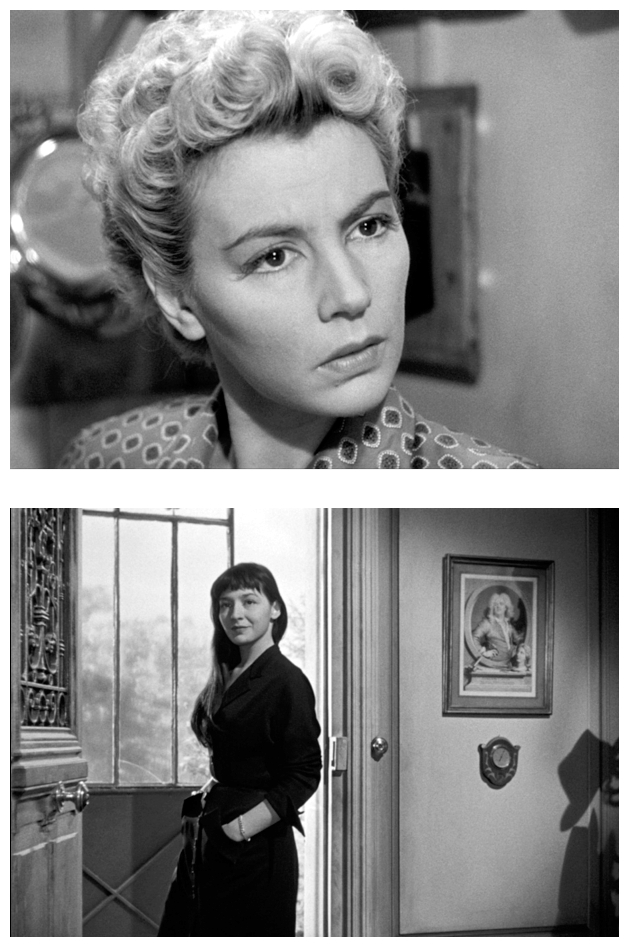

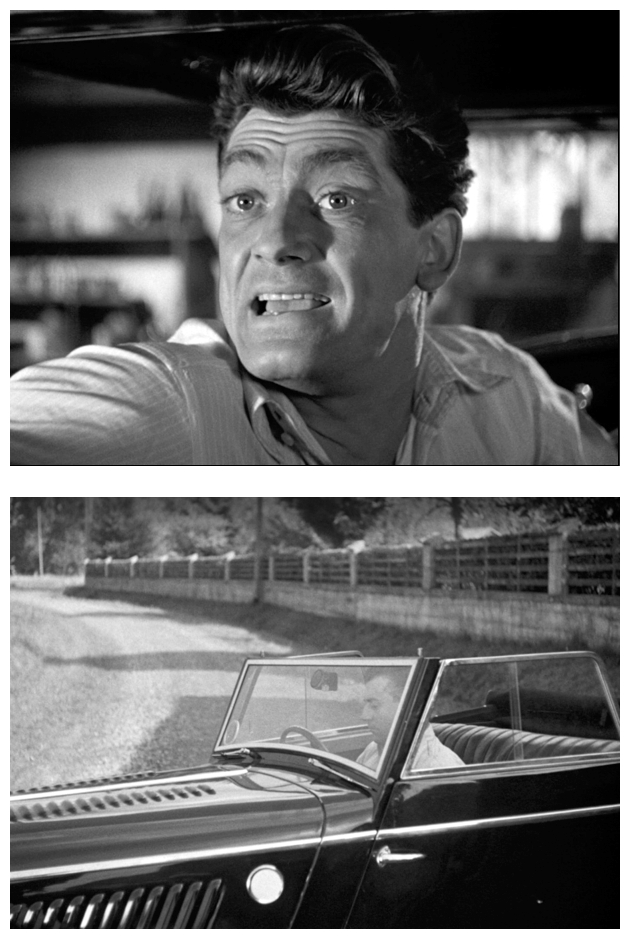

Popular poet Orpheus (Jean Marais), disillusioned and somewhat dissatisfied with his marriage to Eurydice (Marie Déa), is taken on a bizarre journey by Death who has assumed the form of a captivating woman known only as the Princess (María Casares), accompanied by her chauffeur Heurtebise (François Périer). Orpheus soon becomes obsessed with the Princess, and also with the cryptic messages that come through the radio of the car she leaves behind (a reference to the coded messages that the BBC concealed in their wartime transmissions for the French Resistance). When the Eurydice is killed by Death’s motorcycle henchmen, Heurtebise suggests he lead Orpheus into the Underworld in order to reclaim her. Orpheus reveals that he may have fallen in love with Death who has visited him in his dreams. Heurtebise asks Orpheus which woman he will betray, Death or Eurydice? Orpheus enters the afterlife by donning a pair of surgical gloves left behind by the Princess after Eurydice’s death. In the ruins of the Underworld (shot in the blitzed remains of the Saint Cyr Military Academy), Orpheus finds himself before a tribunal which is interrogating everyone involved in the death of Eurydice.

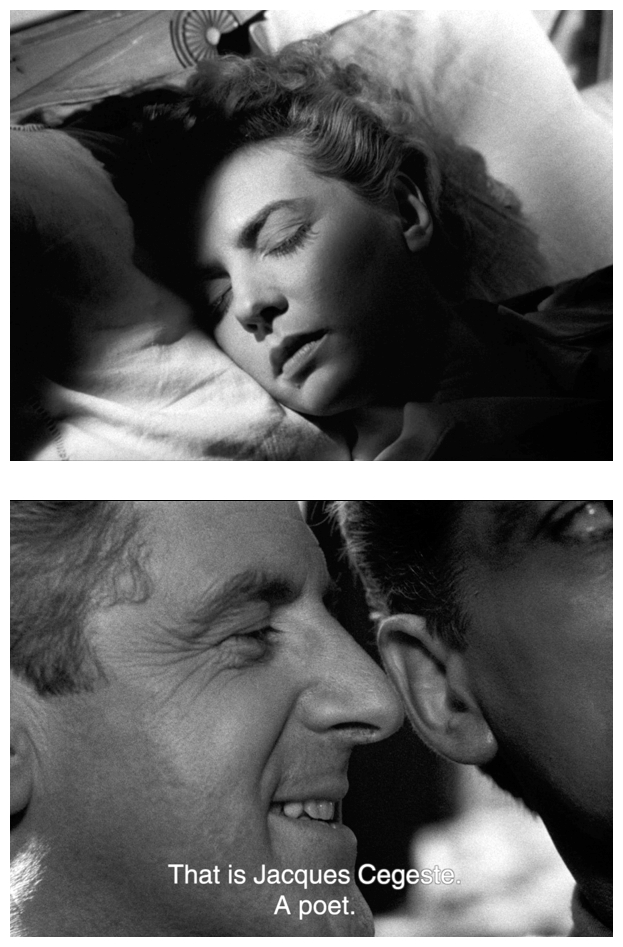

The tribunal declares that Death has illegally claimed Eurydice and they return her to life with one condition: Orpheus must never look upon her for the rest of his life or lose her again forever. Orpheus agrees and returns home with Eurydice, accompanied by Heurtebise, who has been assigned by the tribunal to assist the couple in adapting to their new restrictive life together. Eurydice visits the garage where Orpheus constantly listens to the limousine’s radio in search of the unknown poetry. She sits in the backseat. When Orpheus glances at her in the mirror, Eurydice disappears. When a murderous mob from the Café des Poètes arrives, Orpheus confronts them armed with a revolver, but is disarmed and shot. Orpheus dies and finds himself in the Underworld. This time, he declares his love to Death who has decided to herself die in order that he might become an ‘Immortal Poet’. The tribunal this time sends Orpheus and Eurydice back to the living world with no memories of the previous events. Orpheus learns that he is to be a father, and his life begins anew. Meanwhile, Death and Heurtebise walk through the ruins of the Underworld towards an unspecified but unpleasant fate.

The centrepiece of a unique trilogy – along with The Blood Of A Poet (1930) and Testament Of Orpheus (1960) – Cocteau’s Orpheus (1950) is often described as a cinematic poem, which is fair enough. But unlike the director’s relatively graspable Beauty And The Beast, Orpheus is a perplexing pseudo-Noir with fertile New Wave European pretentiousness, an exercise in symbolism and surreal special effects. As the poet Orpheus, the preternaturally handsome and regal-looking Jean Marais finds himself torn between two worshipful lovers, his wife Eurydice (played with flirtatious warmth by Marie Déa) and Death herself, in the form of a stoic Princess. As if this triangle wasn’t complicated enough, Cocteau ups-the-ante by spending a good deal of time with Princess Death’s driver, the sad but sensitive Heurtebise, charting his gentle love for the neglected Eurydice. In a different context, one can imagine a free-wheeling romantic comedy built around these same four befuddled characters – but that’s not what Cocteau had in mind.

Rather, we are treated to the textures and illogic of a living dream, clearly identified as such by the protagonist. From the simple, barely noticeable touches (negative rear-projected backgrounds as Orpheus approaches Death’s castle, an invisible hand belonging to to ghostly Heurtebise hanging up the phone, etc.) to the showcase mirror penetrations (using a vat of mercury to create the effect) and bleak windy netherworlds, no-one does this sort of thing better than Cocteau. His trademark slow-motion reversals are in full force here, especially effective as magic gloves envelope hands or when the Princess summons an entranced Eurydice from her deathbed. It’s rather ironic that the best-remembered effect in this entire movie is the stunned post-dead heroine vanishing instantly when Orpheus accidentally catches a glimpse of her in his rear-view mirror – a simple cut-and-resume exercise that any first-year film student can achieve with ease.

Not for all tastes but, if indulgent escape into surreal thematics and jaw-dropping visuals are to your liking, Orpheus does justice to its legend while creating a significant new one in the process. Many more films were made from Cocteau’s scripts and stories, the most successful of these being Jean-Pierre Melville‘s The Terrible Children (1950), in which we are drawn in, almost against our will, to the claustrophobic yet strangely liberating world of the semi-sane. The year both Orpheus and The Terrible Children were released also saw the modest beginnings of a different sort of genre cinema. The post-war world of progress, technology and the Bomb was creating another kind of mythology altogether. But that’s another story for another time. I’ll be back next week come hell and high water to assault your senses with another so-called classic fetched from the deepest depths of the Los Angeles sewerage system for…Horror News! Toodles!

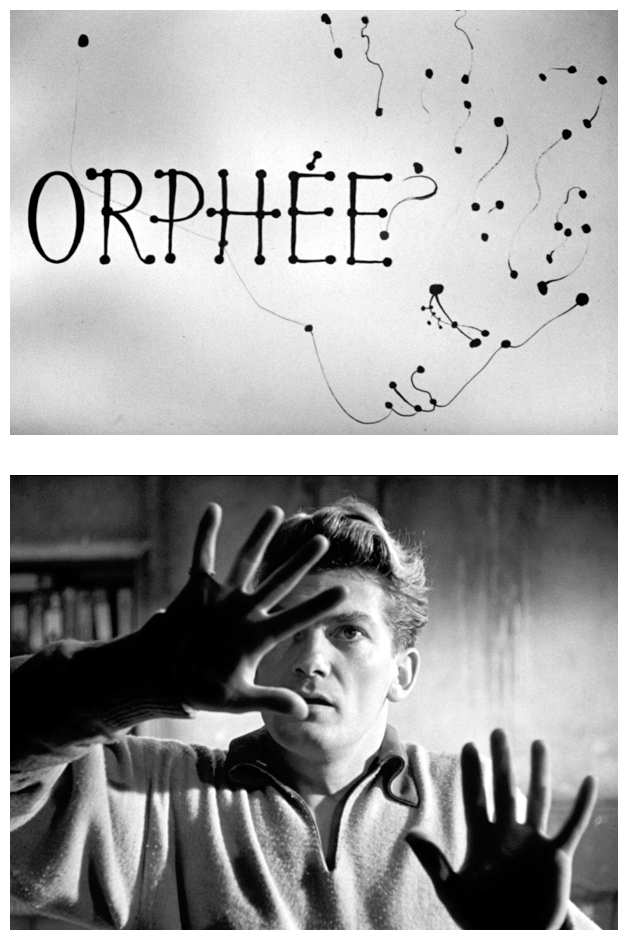

Orpheus (1950)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews