SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

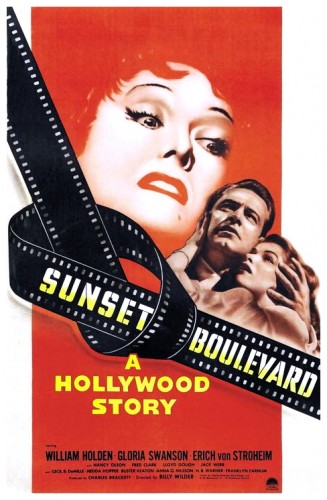

“In Hollywood of the fifties, the obscure screenplay writer Joe Gillis is not able to sell his work to the studios, is full of debts and is thinking in returning to his hometown to work in an office. While trying to escape from his creditors, he has a flat tire and parks his car in a decadent mansion in Sunset Boulevard. He meets the owner and former silent-movie star Norma Desmond, who lives alone with her butler and driver Max Von Mayerling. Norma is demented and believes she will return to the cinema industry, and is protected and isolated from the world by Max, who was her director and husband in the past and still loves her. Norma proposes Joe to move to the mansion and help her in writing a screenplay for her comeback to the cinema, and the small-time writer becomes her lover and gigolo. When Joe falls in love for the young aspirant writer Betty Schaefer, Norma becomes jealous and completely insane and her madness leads to a tragic end.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

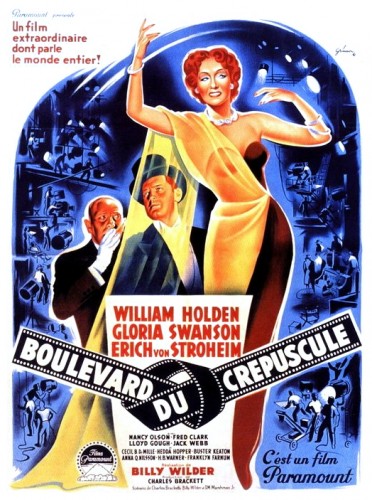

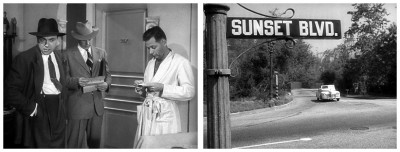

Sunset Boulevard (1950) opens with a corpse floating face down in a dank swimming pool. In classic Film Noir style, the first-person voiceover explains that we are about to learn how the unfortunate Joe Gillis (William Holden) got there. The film flashes back to a lurid story-line set in the faded grandeur of the Hollywood Hills. Six months earlier Gillis had been at a dead end, a hack screenwriter confronted by endless refusals. Broke and fleeing repo-men out to reclaim his car, he pulls into a dusty Sunset Boulevard driveway to change his tyre. Gillis is welcomed into the dilapidated mansion by a mysterious manservant, Max (Erich Von Stroheim) and is introduced to the owner, the once-famous but now forgotten silent movie star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson). They share their disillusionment over modern Hollywood, and Gillis accepts the job of rewriting the movie script that Norma believes will bring her back to the top.

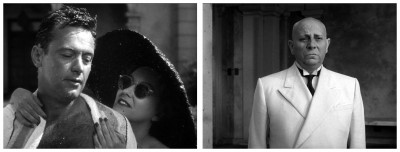

Over the next few months he finds himself trapped within the coils of Norma’s delusions. Still Hollywood aristocracy, Norma can call on the likes of Cecil B. DeMille to pander to her fancies, but she is merely being placated or patronised. Gillis begins to realise that he is trapped within her dream world, and he has become her ‘toy-boy’. It turns out that the devoted Max was once her director, and even he supports her delusion, feeding her fan mail that he forges. When Gillis attempts to break free, Norma attempts suicide and, when this fails to recapture him, in a rage she shoots him. Only when the press arrive to capture Norma’s arrest for murdering Gillis does the profound illusion that she has been living within become clear. Max once again directs Norma as she descends the stairs, the cameras roll and so do the credits. In the illusionistic madness that is Hollywood, Norma thinks she is once again a star.

Over the next few months he finds himself trapped within the coils of Norma’s delusions. Still Hollywood aristocracy, Norma can call on the likes of Cecil B. DeMille to pander to her fancies, but she is merely being placated or patronised. Gillis begins to realise that he is trapped within her dream world, and he has become her ‘toy-boy’. It turns out that the devoted Max was once her director, and even he supports her delusion, feeding her fan mail that he forges. When Gillis attempts to break free, Norma attempts suicide and, when this fails to recapture him, in a rage she shoots him. Only when the press arrive to capture Norma’s arrest for murdering Gillis does the profound illusion that she has been living within become clear. Max once again directs Norma as she descends the stairs, the cameras roll and so do the credits. In the illusionistic madness that is Hollywood, Norma thinks she is once again a star.

Director Billy Wilder and his writing partner Charles Brackett attack agents, directors, producers and studio heads. More than just assaulting those who have made Hollywood a place where talent and integrity have little meaning, they concocted a veritable funeral elegy to old-style Hollywood films, from the elegant romances and comedies of the silent era to naive backlot romances of the early sound era to adaptations of brooding gothic novels to horror films. Not only does the morbid death-obsessed plot parallel Dracula’s Daughter (1936), but the film abounds in horror-movie references and imagery. What better locale for a ‘ghost’ story (about a woman long thought dead) than Hollywood, a town built on illusions and delusions, where people grow old but remain young on celluloid, where people become has-beens before they’ve even made it.

Director Billy Wilder and his writing partner Charles Brackett attack agents, directors, producers and studio heads. More than just assaulting those who have made Hollywood a place where talent and integrity have little meaning, they concocted a veritable funeral elegy to old-style Hollywood films, from the elegant romances and comedies of the silent era to naive backlot romances of the early sound era to adaptations of brooding gothic novels to horror films. Not only does the morbid death-obsessed plot parallel Dracula’s Daughter (1936), but the film abounds in horror-movie references and imagery. What better locale for a ‘ghost’ story (about a woman long thought dead) than Hollywood, a town built on illusions and delusions, where people grow old but remain young on celluloid, where people become has-beens before they’ve even made it.

Sunset Boulevard also laments the passing of Film Noir, from which it borrows several elements: Fatalism; Los Angeles backdrop; first-person narration; a weak tarnished hero; and his destruction by romantic entanglement with a strong manipulative (and also doomed) woman. The narration has been criticised in some circles for being overly descriptive and hyperbolic, but this is precisely how a hack two-scripts-a-week screenwriter like Joe would talk. Joe’s B-movie-style narration tells us that he is just as obsolete as Norma in modern Hollywood.

Sunset Boulevard also laments the passing of Film Noir, from which it borrows several elements: Fatalism; Los Angeles backdrop; first-person narration; a weak tarnished hero; and his destruction by romantic entanglement with a strong manipulative (and also doomed) woman. The narration has been criticised in some circles for being overly descriptive and hyperbolic, but this is precisely how a hack two-scripts-a-week screenwriter like Joe would talk. Joe’s B-movie-style narration tells us that he is just as obsolete as Norma in modern Hollywood.

At first, the film seems to be about how pathetic Norma is and how unfortunate Joe is to have fallen into her clutches, but that’s only if we go along with Joe’s perspective. His cynical narration tries to get our sympathy by speaking of her only in pitying terms, but Norma is the one who lowered herself to be with him. Norma was a great star and, as her Charlie Chaplin imitation confirms, still has talent (“I AM big, it’s the pictures that got small!”) while he has never accomplished anything. Joe thinks he’s giving Norma a break by staying with her, but she’s no fool. She knows he’s no more than a gigolo and that it is she who is using him.

At first, the film seems to be about how pathetic Norma is and how unfortunate Joe is to have fallen into her clutches, but that’s only if we go along with Joe’s perspective. His cynical narration tries to get our sympathy by speaking of her only in pitying terms, but Norma is the one who lowered herself to be with him. Norma was a great star and, as her Charlie Chaplin imitation confirms, still has talent (“I AM big, it’s the pictures that got small!”) while he has never accomplished anything. Joe thinks he’s giving Norma a break by staying with her, but she’s no fool. She knows he’s no more than a gigolo and that it is she who is using him.

Wilder’s ingenuity in involving Swanson, Von Stroheim, DeMille, Buster Keaton, Hedda Hopper, H.B. Warner and others in his project is what makes the movie work so wonderfully. Were these past-their-sell-by-date immortals from the early days of Hollywood in on the joke? If they were, then Louis B. Mayer certainly wasn’t, and he rallied at Wilder: “You bastard, you have disgraced the industry that made and fed you! You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!” At the heart of the film is the double act between Swanson as the deluded veteran star still convinced that her audience of fans await her return to the limelight, and Von Stroheim (who had indeed directed Swanson many times during their heyday) as her former director and now butler, who will do anything to protect her.

Wilder’s ingenuity in involving Swanson, Von Stroheim, DeMille, Buster Keaton, Hedda Hopper, H.B. Warner and others in his project is what makes the movie work so wonderfully. Were these past-their-sell-by-date immortals from the early days of Hollywood in on the joke? If they were, then Louis B. Mayer certainly wasn’t, and he rallied at Wilder: “You bastard, you have disgraced the industry that made and fed you! You should be tarred and feathered and run out of Hollywood!” At the heart of the film is the double act between Swanson as the deluded veteran star still convinced that her audience of fans await her return to the limelight, and Von Stroheim (who had indeed directed Swanson many times during their heyday) as her former director and now butler, who will do anything to protect her.

Wilder considered a number of fading screen stars for the role of Norma Desmond, including Mary Pickford, Pola Negri, Mae Murray and even Mae West. He was later unfairly accused of basing Norma’s story on that of the enormously popular silent star Norma Talmadge, who had retired from movie-making in 1930. The casting of Swanson was spot-on – she had been huge but she lost out when talkies arrived. An intelligent woman and a far cry from the deluded fragility of Norma Desmond, she allowed her calculated persona as a silent screen star to be completely exploited by Wilder. Clips from her masterpiece Queen Kelly (1931) are included in Sunset Boulevard, while the grandiose director of that broken epic graciously agreed to play her butler at a time when his own career was practically in ruins.

Wilder considered a number of fading screen stars for the role of Norma Desmond, including Mary Pickford, Pola Negri, Mae Murray and even Mae West. He was later unfairly accused of basing Norma’s story on that of the enormously popular silent star Norma Talmadge, who had retired from movie-making in 1930. The casting of Swanson was spot-on – she had been huge but she lost out when talkies arrived. An intelligent woman and a far cry from the deluded fragility of Norma Desmond, she allowed her calculated persona as a silent screen star to be completely exploited by Wilder. Clips from her masterpiece Queen Kelly (1931) are included in Sunset Boulevard, while the grandiose director of that broken epic graciously agreed to play her butler at a time when his own career was practically in ruins.

Hollywood has been making films about itself since the twenties – What Price Hollywood? (1932), A Star Is Born (1937), It’s A Great Feeling (1949) – and Sunset Boulevard was soon followed by The Bad And The Beautiful (1952), Singin’ In The Rain (1952) and the musical remake of A Star Is Born (1954). It has also been an inspiration for many other so-called ‘Hagsploitation’ films featuring older actresses desperately clinging to their former glory, such as Bette Davis in The Star (1952) and Whatever Happened To Baby Jane? (1962), Joan Crawford in Torch Song (1953), Geraldine Page in Sweet Bird Of Youth (1962), Susan Hayward in Valley Of The Dolls (1967) and Faye Dunaway in Mommie Dearest (1981). Also worthy of mention is The Day Of The Locust (1975), The Last Tycoon (1976) and S.O.B. (1981), all of which depict Hollywood in a very negative light and, like Sunset Boulevard, make use of real backstage settings.

Hollywood has been making films about itself since the twenties – What Price Hollywood? (1932), A Star Is Born (1937), It’s A Great Feeling (1949) – and Sunset Boulevard was soon followed by The Bad And The Beautiful (1952), Singin’ In The Rain (1952) and the musical remake of A Star Is Born (1954). It has also been an inspiration for many other so-called ‘Hagsploitation’ films featuring older actresses desperately clinging to their former glory, such as Bette Davis in The Star (1952) and Whatever Happened To Baby Jane? (1962), Joan Crawford in Torch Song (1953), Geraldine Page in Sweet Bird Of Youth (1962), Susan Hayward in Valley Of The Dolls (1967) and Faye Dunaway in Mommie Dearest (1981). Also worthy of mention is The Day Of The Locust (1975), The Last Tycoon (1976) and S.O.B. (1981), all of which depict Hollywood in a very negative light and, like Sunset Boulevard, make use of real backstage settings.

Andy Warhol‘s remake Heat (1972) was directed by Paul Morrissey starring Joe Dellesandro as Little Joe, a Beverly Hills child actor turned gigolo, and Sylvia Miles as the over-the-hill actress, recycles the story in a truly tawdry West Hollywood, but it captures little of the poignancy or cynicism of Wilder’s original. From 1953 Gloria Swanson herself worked with Richard Stapley and Dickson Hughes on a musical version entitled Boulevard! Stapley and Hughes first approached Swanson about appearing in a musical revue they had written, but Swanson stated that she would return to the stage only in a musical version of her comeback film. Within a week Stapley and Dickson had written three songs which Swanson had approved, but the show never eventuated. After more than forty years and many attempts to turn Sunset Boulevard into a musical, this feat was finally accomplished by Andrew Lloyd Webber in 1993 starring Glenn Close as Norma Desmond. It’s on this musical note I’ll wrap-up this week’s burnt offering, and respectfully request your presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another cinematic pedigree from Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Andy Warhol‘s remake Heat (1972) was directed by Paul Morrissey starring Joe Dellesandro as Little Joe, a Beverly Hills child actor turned gigolo, and Sylvia Miles as the over-the-hill actress, recycles the story in a truly tawdry West Hollywood, but it captures little of the poignancy or cynicism of Wilder’s original. From 1953 Gloria Swanson herself worked with Richard Stapley and Dickson Hughes on a musical version entitled Boulevard! Stapley and Hughes first approached Swanson about appearing in a musical revue they had written, but Swanson stated that she would return to the stage only in a musical version of her comeback film. Within a week Stapley and Dickson had written three songs which Swanson had approved, but the show never eventuated. After more than forty years and many attempts to turn Sunset Boulevard into a musical, this feat was finally accomplished by Andrew Lloyd Webber in 1993 starring Glenn Close as Norma Desmond. It’s on this musical note I’ll wrap-up this week’s burnt offering, and respectfully request your presence next week, when your leg will be crudely humped by another cinematic pedigree from Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews