SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“On Isla Nublar, a new park has just been built with genetically engineered dinosaurs. Tragedy strikes when one of the workers is killed by a velociraptor. The founder of the park John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) requests paleontologist Doctor Alan Grant (Sam Neill) and his assistant, Doctor Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) to come to the park and ensure that it is safe. Also joining them are Hammond’s lawyer Donald Gennaro (Martin Ferrero) and chaos theorist Doctor Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum). When they reach the island, they are amazed to discover that Hammond has created living dinosaurs. However, at the same time they all have their doubts. Later, Hammond’s grandchildren Lex (Ariana Richards) and Tim (Joseph Mazzello) join the group in a tour of the park. Sattler leaves the tour to take care of an ill triceratops. Soon the power in the park is shut down by computer systems geek Dennis Nedry (Wayne Knight) who wishes to steal embryos from the park to sell to a secret buyer. In the process, many dinosaurs escape their paddocks, including the deadly tyrannosaurus rex, who, during a thunderstorm, escapes his paddock and attacks the children, and eats Gennaro. Malcolm is injured, and Grant and the children are then lost in the park. Meanwhile, Hammond, Sattler and the rest of the operations team learn that Nedry (who in the meantime has been killed) has locked up the computer system to cover his tracks. They attempt to get power back in the park in order to escape the island. After shutting down the system, then restoring it, the group realizes that velociraptors are also on the loose, and are now on the hunt for the visitors.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

By the early nineties Steven Spielberg had established his position as the preeminent Hollywood director, but his films over the previous decade had largely decayed into cloying cuteness and overblown sentimentality. So the buzz that Spielberg had secured the rights to Michael Crichton‘s exciting novel Jurassic Park (published 1990) did not settle well with fans (cuddly dinosaurs speaking in childlike voices?) but anyone emerging from a cinema after the two-hour screening must have felt that dinosaurs were truly walking the earth. Spielberg was back in form – Jurassic Park (1993) wasn’t just good, it was Jaws (1975) good! It tells of one man’s dream to create a unique game preserve on a remote jungle island near Costa Rica. Billionaire John Hammond (Richard Attenborough) has amassed a core group of experts who have discovered how to genetically engineer live dinosaurs from their fossilised DNA remains found in the blood of prehistoric mosquitoes encased in amber, and has populated his scientific Disneyland with long-extinct breeds of dangerous carnivores.

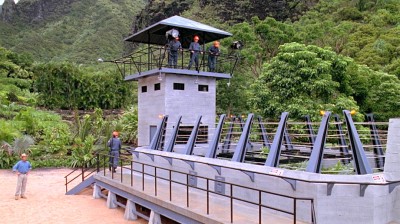

Invited by Hammond to be the first to explore the wonders of his totally fabricated prehistoric park are paleontologist Alan Grant (Sam Neill), paleobotanist Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) and mathematician Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum). The group find themselves fighting for their lives when vital security mechanisms malfunction, allowing the manufactured creatures to run wild. Worse, the vicious breed of dinosaur – the bird-like velociraptors – have been secretly reproducing at an alarming rate and are threatening to migrate from the island. On top of all that, there’s also an industrial espionage saboteur from a rival ‘consumer biologicals’ corporation who will have to contend with the prehistoric monsters.

Invited by Hammond to be the first to explore the wonders of his totally fabricated prehistoric park are paleontologist Alan Grant (Sam Neill), paleobotanist Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern) and mathematician Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum). The group find themselves fighting for their lives when vital security mechanisms malfunction, allowing the manufactured creatures to run wild. Worse, the vicious breed of dinosaur – the bird-like velociraptors – have been secretly reproducing at an alarming rate and are threatening to migrate from the island. On top of all that, there’s also an industrial espionage saboteur from a rival ‘consumer biologicals’ corporation who will have to contend with the prehistoric monsters.

When Crichton’s book was first published in 1990, many readers remarked how it resembled a screenplay treatment thinly masquerading as a novel. Hardly an earth-shattering observation considering Crichton is a well-respected director in his own right. While his novel The Andromeda Strain (1970) was brought to the screen by director Robert Wise, and The Terminal Man (1974) by Mike Hodges, Crichton directed his own scripts for The First Great Train Robbery (1979), Looker (1981) and Runaway (1984) after adapting and directing Robin Cook‘s medical thriller Coma (1977). Almost all of Crichton’s output, either in print or on screen, has been preoccupied with the same central theme: Cutting-edge technology cannot always be trusted. Jurassic Park continues this personal dissertation by highlighting the unpredictable aspects of biotechnology which Crichton maintains must be researched more fully before it’s allowed to completely revolutionise mankind.

When Crichton’s book was first published in 1990, many readers remarked how it resembled a screenplay treatment thinly masquerading as a novel. Hardly an earth-shattering observation considering Crichton is a well-respected director in his own right. While his novel The Andromeda Strain (1970) was brought to the screen by director Robert Wise, and The Terminal Man (1974) by Mike Hodges, Crichton directed his own scripts for The First Great Train Robbery (1979), Looker (1981) and Runaway (1984) after adapting and directing Robin Cook‘s medical thriller Coma (1977). Almost all of Crichton’s output, either in print or on screen, has been preoccupied with the same central theme: Cutting-edge technology cannot always be trusted. Jurassic Park continues this personal dissertation by highlighting the unpredictable aspects of biotechnology which Crichton maintains must be researched more fully before it’s allowed to completely revolutionise mankind.

But the Jurassic Park concept is hardly new in the Crichton canon. It’s essentially a reworking of Westworld (1973), Crichton’s own theatrical motion picture directorial debut – the year before he had directed the made-for-television movie Pursuit (1972) based on his own novel Binary. Westworld’s premise featured a futuristic vacation resort called Delos, menaced by a short-circuited robot gunfighter (Yul Brynner) in a Wild West fantasy world. A less successful sequel entitled Futureworld (1976) followed, as did the doomed television series Beyond Westworld (1980). Jurassic Park is the same plot magnified, finessed and, with reference to the humid jungle setting, includes dashes of Congo (1995) based on another exotic Crichton novel. Congo features a research expedition aided by an almost-human chimpanzee, discovering a race of intelligent militant gorillas in a ruined temple of diamonds deep within the African interior. As a feature in development, Congo languished for many years at various studios despite Crichton’s efforts to get it off the ground. That dismal experience led Crichton to develop Jurassic Park as a novel instead of a film.

But the Jurassic Park concept is hardly new in the Crichton canon. It’s essentially a reworking of Westworld (1973), Crichton’s own theatrical motion picture directorial debut – the year before he had directed the made-for-television movie Pursuit (1972) based on his own novel Binary. Westworld’s premise featured a futuristic vacation resort called Delos, menaced by a short-circuited robot gunfighter (Yul Brynner) in a Wild West fantasy world. A less successful sequel entitled Futureworld (1976) followed, as did the doomed television series Beyond Westworld (1980). Jurassic Park is the same plot magnified, finessed and, with reference to the humid jungle setting, includes dashes of Congo (1995) based on another exotic Crichton novel. Congo features a research expedition aided by an almost-human chimpanzee, discovering a race of intelligent militant gorillas in a ruined temple of diamonds deep within the African interior. As a feature in development, Congo languished for many years at various studios despite Crichton’s efforts to get it off the ground. That dismal experience led Crichton to develop Jurassic Park as a novel instead of a film.

The screenplay was written by David Koepp, then only twenty-nine years old, who had studied screenwriting at UCLA and co-wrote both Apartment Zero (1988) and Death Becomes Her (1992) before being offered Jurassic Park. Since then, Koepp has worked on blockbuster Hollywood films such as The Shadow (1994), Mission Impossible (1996), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), Spider-Man (2002), Panic Room (2002), and Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull (2008). Jurassic Park was photographed by Dean Cundey, arguably Hollywood’s best living cinematographer, who went from cheap exploitation films like Beware The Blob (1972) and Ilsa Harem Keeper Of The Oil Sheiks (1976) to the very best of John Carpenter: Halloween (1978), Escape From New York (1981), The Thing (1982), Big Trouble In Little China (1986). He soon became the busiest cinematographer in Hollywood, the first choice of directors like Robert Zemeckis, Joe Dante, Ron Howard and, of course, Steven Spielberg.

The screenplay was written by David Koepp, then only twenty-nine years old, who had studied screenwriting at UCLA and co-wrote both Apartment Zero (1988) and Death Becomes Her (1992) before being offered Jurassic Park. Since then, Koepp has worked on blockbuster Hollywood films such as The Shadow (1994), Mission Impossible (1996), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), Spider-Man (2002), Panic Room (2002), and Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull (2008). Jurassic Park was photographed by Dean Cundey, arguably Hollywood’s best living cinematographer, who went from cheap exploitation films like Beware The Blob (1972) and Ilsa Harem Keeper Of The Oil Sheiks (1976) to the very best of John Carpenter: Halloween (1978), Escape From New York (1981), The Thing (1982), Big Trouble In Little China (1986). He soon became the busiest cinematographer in Hollywood, the first choice of directors like Robert Zemeckis, Joe Dante, Ron Howard and, of course, Steven Spielberg.

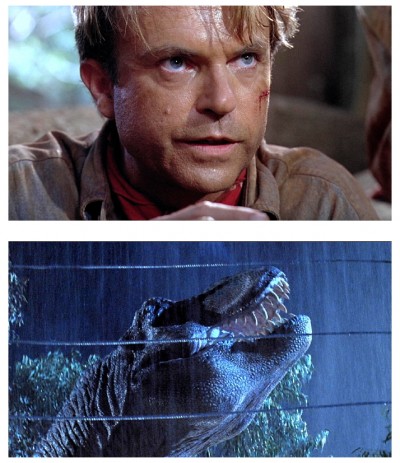

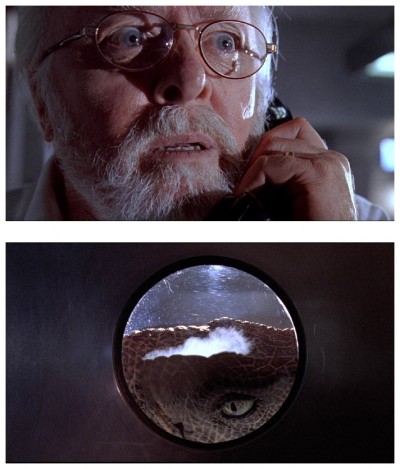

The film is almost perfectly cast with experienced professional actors such as Sam Neill, Laura Dern, Jeff Goldblum, Samuel L. Jackson, Bob Peck and Martin Ferrero. The highlight in this department is the reappearance of Sir Richard Attenborough, after spending more than fourteen years behind the cameras. As a director and producer, he won four BAFTAs, three Golden Globes and two Oscars for Gandhi (1983) and, as an actor, is best known for his roles in Brighton Rock (1947), The Great Escape (1963), Ten Rillington Place (1971) and Miracle On 34th Street (1994). The only disappointment amongst the cast is comedy actor Wayne Knight as the bumbling computer expert/espionage agent Dennis Nedry, although it’s not entirely his fault, as his character seems to be so poorly conceived in the first place. It’s as if he’s been lifted out of an entirely different film, cut-and-pasted from some third-rate teen laugh-riot.

The film is almost perfectly cast with experienced professional actors such as Sam Neill, Laura Dern, Jeff Goldblum, Samuel L. Jackson, Bob Peck and Martin Ferrero. The highlight in this department is the reappearance of Sir Richard Attenborough, after spending more than fourteen years behind the cameras. As a director and producer, he won four BAFTAs, three Golden Globes and two Oscars for Gandhi (1983) and, as an actor, is best known for his roles in Brighton Rock (1947), The Great Escape (1963), Ten Rillington Place (1971) and Miracle On 34th Street (1994). The only disappointment amongst the cast is comedy actor Wayne Knight as the bumbling computer expert/espionage agent Dennis Nedry, although it’s not entirely his fault, as his character seems to be so poorly conceived in the first place. It’s as if he’s been lifted out of an entirely different film, cut-and-pasted from some third-rate teen laugh-riot.

The real stars of Jurassic Park, the dinosaurs themselves, were created with groundbreaking computer generated imagery by Industrial Light & Magic in conjunction with life-sized animatronic dinosaurs designed by Mark ‘Crash’ McCreery and built by Stan Winston. Despite spending US$65 million on marketing, many viewers still assumed that all the dinosaurs seen were animations generated by computer, when in fact most of the CGI used was used for ‘grip removal’ in order to hide the huge animatronic rigs and wires controlling Stan Winston’s creatures. Breaking all box-office records two decades ago, Jurassic Park is still cited by critics and filmgoers alike as one of the greatest action thrillers ever made, listed the 35th most thrilling film of all-time by the American Film Institute.

The real stars of Jurassic Park, the dinosaurs themselves, were created with groundbreaking computer generated imagery by Industrial Light & Magic in conjunction with life-sized animatronic dinosaurs designed by Mark ‘Crash’ McCreery and built by Stan Winston. Despite spending US$65 million on marketing, many viewers still assumed that all the dinosaurs seen were animations generated by computer, when in fact most of the CGI used was used for ‘grip removal’ in order to hide the huge animatronic rigs and wires controlling Stan Winston’s creatures. Breaking all box-office records two decades ago, Jurassic Park is still cited by critics and filmgoers alike as one of the greatest action thrillers ever made, listed the 35th most thrilling film of all-time by the American Film Institute.

There’s no denying the impact of ILM‘s computer-generated visual effects, which sparked a revolution in movies almost as profound as the emergence of sound in The Jazz Singer (1927). It proved to filmmakers all over the world that their visions, previously thought unfeasible, were now possible. Inspired by the success of Jurassic Park, George Lucas started work on Star Wars I The Phantom Menace (1999), Stanley Kubrick put A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) into production, and Peter Jackson decided to explore his love of high fantasy with The Lord Of The Rings (2001) trilogy. The technology had reached the point that filmmakers were limited only by their own imaginations. It’s also rather apt that Jurassic Park should utilise the exact same techniques that visionary Michael Crichton explored in Looker (1981), in which celebrities and world leaders are re-created as computer-generated images for sinister purposes. Life is indeed imitating art.

There’s no denying the impact of ILM‘s computer-generated visual effects, which sparked a revolution in movies almost as profound as the emergence of sound in The Jazz Singer (1927). It proved to filmmakers all over the world that their visions, previously thought unfeasible, were now possible. Inspired by the success of Jurassic Park, George Lucas started work on Star Wars I The Phantom Menace (1999), Stanley Kubrick put A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) into production, and Peter Jackson decided to explore his love of high fantasy with The Lord Of The Rings (2001) trilogy. The technology had reached the point that filmmakers were limited only by their own imaginations. It’s also rather apt that Jurassic Park should utilise the exact same techniques that visionary Michael Crichton explored in Looker (1981), in which celebrities and world leaders are re-created as computer-generated images for sinister purposes. Life is indeed imitating art.

Speaking of which, Jurassic Park is also an ideal example of a self-reflexive film. It recognises that, like the characters in the story, we would love to see real dinosaurs running around and, rather than give us Ray Harryhausen-style stop-motion effects as seen in The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) or The Valley Of Gwangi (1969), Spielberg and his team of special effects artists needed to create these monsters so believably that we fall into a kind of sublime awe in their presence, as the characters in the movie do. But Jurassic Park is smarter still. Spielberg includes a sequence not in the novel, where we get a simple panning shot of the park’s gift shop, shelves full of Jurassic Park merchandise (at one point Spielberg actually considered building a real Universal Studios theme park first to shoot the film in).

Speaking of which, Jurassic Park is also an ideal example of a self-reflexive film. It recognises that, like the characters in the story, we would love to see real dinosaurs running around and, rather than give us Ray Harryhausen-style stop-motion effects as seen in The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) or The Valley Of Gwangi (1969), Spielberg and his team of special effects artists needed to create these monsters so believably that we fall into a kind of sublime awe in their presence, as the characters in the movie do. But Jurassic Park is smarter still. Spielberg includes a sequence not in the novel, where we get a simple panning shot of the park’s gift shop, shelves full of Jurassic Park merchandise (at one point Spielberg actually considered building a real Universal Studios theme park first to shoot the film in).

All the stuff on display in this shot utilises the graphic design of the film itself and the excess – from pencil cases to lunch boxes, from T-shirts to the actual Making Of Jurassic Park book by Don Shay and Jody Duncan – is also self-reflexive of the kinds of movie merchandise that Spielberg’s own output has been instrumental in establishing. What does this shot tell us? It tells us that Spielberg was well aware of how overly commodified his films had become and, within the context of the movie, after the dinosaurs have broken loose and the park is clearly never going to open, this merchandising bubble must ultimately burst. Spielberg’s films since Jurassic Park have been much less merchandised than they were in the eighties.

All the stuff on display in this shot utilises the graphic design of the film itself and the excess – from pencil cases to lunch boxes, from T-shirts to the actual Making Of Jurassic Park book by Don Shay and Jody Duncan – is also self-reflexive of the kinds of movie merchandise that Spielberg’s own output has been instrumental in establishing. What does this shot tell us? It tells us that Spielberg was well aware of how overly commodified his films had become and, within the context of the movie, after the dinosaurs have broken loose and the park is clearly never going to open, this merchandising bubble must ultimately burst. Spielberg’s films since Jurassic Park have been much less merchandised than they were in the eighties.

After the enormous success of the film, Spielberg asked Crichton to write a sequel novel, leading to The Lost World (published 1995) which in turn was filmed as The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), also directed by Spielberg and written by Koepp. Jurassic Park III (2001), produced by Spielberg and directed by Joe Johnston, incorporated unused elements from Crichton’s original novels, and a fourth movie entitled Jurassic World (2015) is currently in pre-production to be written and directed by the filmmaking team of Colin Trevorrow and Derek Connolly, whose only other effort is the multi-award-winning time-travel comedy Safety Not Guaranteed (2012). Although the movie has been cast (Chris Pratt, Bryce Dallas Howard, Vincent D’Onofrio, amongst others), details concerning the story have yet to be released. According to Trevorrow, “Reboot is a strong word. This is a new sci-fi terror adventure set twenty-two years after the horrific events of Jurassic Park.” With a title like that, it’s hard not to imagine a combination of Jurassic Park and Westworld with Terminator-style unstoppable robot dinosaurs in cowboy outfits, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll wish you a fair fondue and look forward to enjoying your company seven days from now, to continue our eternal quest to find the second-best film in the entire universe for…Horror News! Toodles!

After the enormous success of the film, Spielberg asked Crichton to write a sequel novel, leading to The Lost World (published 1995) which in turn was filmed as The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), also directed by Spielberg and written by Koepp. Jurassic Park III (2001), produced by Spielberg and directed by Joe Johnston, incorporated unused elements from Crichton’s original novels, and a fourth movie entitled Jurassic World (2015) is currently in pre-production to be written and directed by the filmmaking team of Colin Trevorrow and Derek Connolly, whose only other effort is the multi-award-winning time-travel comedy Safety Not Guaranteed (2012). Although the movie has been cast (Chris Pratt, Bryce Dallas Howard, Vincent D’Onofrio, amongst others), details concerning the story have yet to be released. According to Trevorrow, “Reboot is a strong word. This is a new sci-fi terror adventure set twenty-two years after the horrific events of Jurassic Park.” With a title like that, it’s hard not to imagine a combination of Jurassic Park and Westworld with Terminator-style unstoppable robot dinosaurs in cowboy outfits, but that’s another story for another time. Right now I’ll wish you a fair fondue and look forward to enjoying your company seven days from now, to continue our eternal quest to find the second-best film in the entire universe for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews