SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

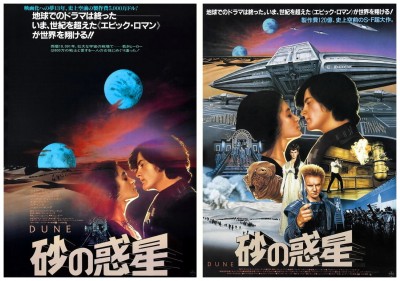

“It is a distant galaxy in the far future year of 10191. Arrakis is a desert planet and the only source of Melange, a vital drug used by the Guild Navigators for space travel from star system to star system. Two rival families, the Atreides and the Harkonnens, fight for control of the mining operations of Melange on Arrakis. When his father Duke Leto Atreides is assassinated by the evil Baron Harkonnen, Duke Leto’s son Paul and Paul’s mother Lady Jessica flee deep into the desert and are befriend by the Fremen, natives of Arrakis. Because of the influence of Melange, Paul learns he has special powers and he can see into the future. Paul unites the Freman, forms an army of warriors and leads them into battle against Baron Harkonnen and the corrupt Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV, who is in league with the Harkonnens, vows to avenge his father and sets out to liberate Arrakis and its people from the Emperor’s rule and fulfill his destiny.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Back in 1965 author Frank Herbert published his epic science fiction novel Dune. Set in the far future amidst a feudal interstellar society in which noble houses control individual planets and owe allegiance to the imperial House Corrino. It tells the story of young Paul Atreides as his family accepts control of the desert planet Arrakis, the only source of the spice Melange, the most important and valuable substance in the universe. It is also a deeply intimate story concerning the coming-of-age and rise to power of Paul Atreides as he takes on his predestined messianic role as the Kwisatz Haderach. Above all else, Dune tells the story of a desert world populated by the Sufi-like Fremen and giant all-devouring worms, its sole industry the harvesting of Melange, a drug that drives the interplanetary transportation system (and thus the economy) on a galactic scale. In other words, it is the equivalent of our oil today, found in the deserts of the Middle East. As all this suggests, in its themes, in its scope, in its characters, the detailed universe of Dune almost overwhelms the story – almost. The plot explores the multi-layered interactions of politics, religion, ecology, technology and human emotion, as the forces of the empire confront each other in a struggle for the control of Arrakis and its spice. Hugely popular, the book won both Hugo and Nebula awards for Best Novel in 1966 and eventually became the world’s best-selling science fiction novel ever.

In 1971, Planet Of The Apes (1968) producer Arthur P. Jacobs was the first to option the film rights to Dune but, since he was busy with Escape From The Planet Of The Apes (1971), Dune was delayed for over a year. Robert Greenhault and Rospo Pallenberg started working on the script due to go before the cameras in 1974, while both David Lean and Charles Jarrott turned down offers to direct. Unfortunately, Jacobs passed away in 1973, and Dune was shelved until a French consortium purchased the film rights and put experimental filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky in the director’s chair. The announced cast and crew sounded like a dream: starring Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, David Carradine, Gloria Swanson, Geraldine Chaplin, Salvador Dali and Herve Villechaize; music by Pink Floyd, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Henry Cow and Magma; design by Chris Foss, Jean (Moebius) Giraud and H.R. Giger; script and special effects supervised by Dan O’Bannon.

In 1971, Planet Of The Apes (1968) producer Arthur P. Jacobs was the first to option the film rights to Dune but, since he was busy with Escape From The Planet Of The Apes (1971), Dune was delayed for over a year. Robert Greenhault and Rospo Pallenberg started working on the script due to go before the cameras in 1974, while both David Lean and Charles Jarrott turned down offers to direct. Unfortunately, Jacobs passed away in 1973, and Dune was shelved until a French consortium purchased the film rights and put experimental filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky in the director’s chair. The announced cast and crew sounded like a dream: starring Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, David Carradine, Gloria Swanson, Geraldine Chaplin, Salvador Dali and Herve Villechaize; music by Pink Floyd, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Henry Cow and Magma; design by Chris Foss, Jean (Moebius) Giraud and H.R. Giger; script and special effects supervised by Dan O’Bannon.

Just as the storyboards, designs and script reached completion, the financial backing dried up. According to Jodorowsky, “The project was sabotaged in Hollywood. It was French and not American. Their message was ‘not Hollywood enough’. There was intrigue, plunder. The storyboard was circulated among all the big studios. Later, the visual aspect of Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977) strangely resembled our style. To make Alien (1979) they called in Moebius, Chris Foss, Giger, Dan O’Bannon, etc. The project signaled to Americans the possibility of making a big show of science fiction films, outside of the scientific rigor of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The project of Dune changed our lives.”

Just as the storyboards, designs and script reached completion, the financial backing dried up. According to Jodorowsky, “The project was sabotaged in Hollywood. It was French and not American. Their message was ‘not Hollywood enough’. There was intrigue, plunder. The storyboard was circulated among all the big studios. Later, the visual aspect of Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977) strangely resembled our style. To make Alien (1979) they called in Moebius, Chris Foss, Giger, Dan O’Bannon, etc. The project signaled to Americans the possibility of making a big show of science fiction films, outside of the scientific rigor of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The project of Dune changed our lives.”

The film rights were sold once more, this time to Dino De Laurentiis, who commissioned Herbert to write a new screenplay. Unfortunately Herbert’s three-hour script was deemed unfilmable, so De Laurentiis hired Rudy Wurlitzer to re-write the screenplay and handed the directing reigns to Ridley Scott. Scott intended to make it into two separate movies and worked on at least three script drafts before giving up and moving on to direct Blade Runner (1982) instead: “But after seven months I dropped out of Dune, by then Rudy Wurlitzer had come up with a first-draft script which I felt was a decent distillation of Frank Herbert’s. But I also realised Dune was going to take a lot more work, at least two-and-a-half years’ worth, and I didn’t have the heart to attack that because my older brother Frank unexpectedly died of cancer while I was prepping the De Laurentiis picture. Frankly, that freaked me out. So I went to Dino and told him the Dune script was his.”

The film rights were sold once more, this time to Dino De Laurentiis, who commissioned Herbert to write a new screenplay. Unfortunately Herbert’s three-hour script was deemed unfilmable, so De Laurentiis hired Rudy Wurlitzer to re-write the screenplay and handed the directing reigns to Ridley Scott. Scott intended to make it into two separate movies and worked on at least three script drafts before giving up and moving on to direct Blade Runner (1982) instead: “But after seven months I dropped out of Dune, by then Rudy Wurlitzer had come up with a first-draft script which I felt was a decent distillation of Frank Herbert’s. But I also realised Dune was going to take a lot more work, at least two-and-a-half years’ worth, and I didn’t have the heart to attack that because my older brother Frank unexpectedly died of cancer while I was prepping the De Laurentiis picture. Frankly, that freaked me out. So I went to Dino and told him the Dune script was his.”

After seeing The Elephant Man (1981), Raffaella De Laurentiis decided that David Lynch should direct the movie. Lynch had received several other directing offers, including Star Wars VI: Return Of The Jedi (1983), but chose to work on Dune (1984) instead, despite not having read the novel or knowing anything about the actual story – but that was soon to change. For the next six months, Lynch concentrated on the script with Eric Bergen and Christopher De Vore, then subsequently worked on five more drafts all by himself. Dune finally went before the cameras in 1983, shot entirely in Mexico with a budget of more than US$40 million, requiring eighty sets built on sixteen sound stages and seventeen thousand cast and crew. Two hundred workers spent two months hand-clearing three square miles of Mexican desert for location shooting. The final product was almost three hours long, but the film’s financiers Universal Studios demanded a standard two-hour cut of the film, so Lynch excised numerous scenes, filmed new scenes simplifying certain plot elements, added a few voice-overs and a new introduction.

After seeing The Elephant Man (1981), Raffaella De Laurentiis decided that David Lynch should direct the movie. Lynch had received several other directing offers, including Star Wars VI: Return Of The Jedi (1983), but chose to work on Dune (1984) instead, despite not having read the novel or knowing anything about the actual story – but that was soon to change. For the next six months, Lynch concentrated on the script with Eric Bergen and Christopher De Vore, then subsequently worked on five more drafts all by himself. Dune finally went before the cameras in 1983, shot entirely in Mexico with a budget of more than US$40 million, requiring eighty sets built on sixteen sound stages and seventeen thousand cast and crew. Two hundred workers spent two months hand-clearing three square miles of Mexican desert for location shooting. The final product was almost three hours long, but the film’s financiers Universal Studios demanded a standard two-hour cut of the film, so Lynch excised numerous scenes, filmed new scenes simplifying certain plot elements, added a few voice-overs and a new introduction.

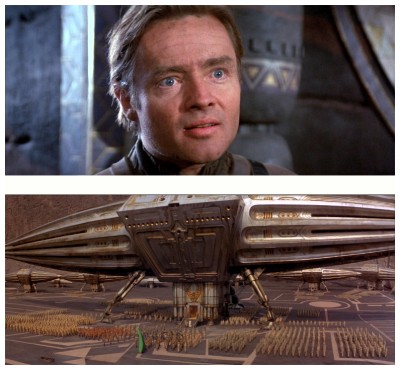

Lynch manages to capture the exact images of those wondrous planets, palace chambers and creatures we imagined while reading Herbert’s novel. Indeed, the first part of the film, including the noble Atreides family’s arrival to rule the desert planet, contains some of the most impressive visuals in science fiction cinema history. Unfortunately, in order to establish the look of the film, Lynch takes so long to get his story going that for the next ninety minutes he has to rush through Herbert’s plot, hoping that readers will fill-in the gaps, recognise the characters who whiz past and be familiar with their motives and loyalties. Those viewers who haven’t read the best-selling novel may be totally dumbfounded, while those familiar with the book will probably be muttering, “I can’t believe they left that part out!” Admittedly, the novel has too many characters with similar powers but, on a superficial level, they are different archetypes with different cultural backgrounds. In the movie, unfortunately, the unenlightened viewer is rarely given a chance to work out who anyone is or what they’re capable of doing.

Lynch manages to capture the exact images of those wondrous planets, palace chambers and creatures we imagined while reading Herbert’s novel. Indeed, the first part of the film, including the noble Atreides family’s arrival to rule the desert planet, contains some of the most impressive visuals in science fiction cinema history. Unfortunately, in order to establish the look of the film, Lynch takes so long to get his story going that for the next ninety minutes he has to rush through Herbert’s plot, hoping that readers will fill-in the gaps, recognise the characters who whiz past and be familiar with their motives and loyalties. Those viewers who haven’t read the best-selling novel may be totally dumbfounded, while those familiar with the book will probably be muttering, “I can’t believe they left that part out!” Admittedly, the novel has too many characters with similar powers but, on a superficial level, they are different archetypes with different cultural backgrounds. In the movie, unfortunately, the unenlightened viewer is rarely given a chance to work out who anyone is or what they’re capable of doing.

Herbert’s immensely popular novel depicts complex groupings: Mentats, Bene Gesserit, Spacing Guild, the Landsraad, the Sardaukar, together with the fiefdoms of Corrino, Atreides and Harkonnen. Moreover, Herbert’s prose looks forward and back at the same time as it relates events in the present, so it’s to Lynch’s great credit that he manages to retain a flavour of all this in full. But in doing so, he has to encapsulate the written memoirs of Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen), the inner thoughts of the major characters, as well as various dreams and visions. Lynch’s recreation of these narrative devices and internal monologues does not entirely work, in that they can seem awkward or distracting. As mentioned before, the sometimes impenetrable dialogue renders the fullness of the film inaccessible to all except those with an intimate knowledge of the source novel.

Herbert’s immensely popular novel depicts complex groupings: Mentats, Bene Gesserit, Spacing Guild, the Landsraad, the Sardaukar, together with the fiefdoms of Corrino, Atreides and Harkonnen. Moreover, Herbert’s prose looks forward and back at the same time as it relates events in the present, so it’s to Lynch’s great credit that he manages to retain a flavour of all this in full. But in doing so, he has to encapsulate the written memoirs of Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen), the inner thoughts of the major characters, as well as various dreams and visions. Lynch’s recreation of these narrative devices and internal monologues does not entirely work, in that they can seem awkward or distracting. As mentioned before, the sometimes impenetrable dialogue renders the fullness of the film inaccessible to all except those with an intimate knowledge of the source novel.

Nevertheless the film is visually impressive, with large-scale operatic sequences that require only music and image. The film’s one unexpected success is Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides, who is believable as the messiah of the desert-bound guerrillas known as the Fremen. The character may be poorly conceived and just as inconsistent as it is in the novel, but MacLachlan makes us feel like cheering him on anyway, even though we’re not exactly sure what he’s up to. Likewise Kenneth McMillan as the evil Baron Harkonnen, while wearing some of the ugliest facial makeup around, makes us despise him even though we’re not exactly sure what his villainous plans are. The rest of the cast is rather fleeting in their appearances, some might say wasted: Francesca Annis, Leonardo Cimino, Brad Dourif, Jose Ferrer, Linda Hunt, Freddie Jones, Richard Jordan, Everett McGill, Jack Nance, Jurgen Prochnow, Patrick Stewart, Dean Stockwell, Max Von Sydow, Alicia Witt, Sean Young. As the Beast Rabban, Paul L. Smith speaks only thirty-four words and Sting, as Feyd-Rautha, fares a little better with only ninety words of dialogue – and that’s in the three-hour version!

Nevertheless the film is visually impressive, with large-scale operatic sequences that require only music and image. The film’s one unexpected success is Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides, who is believable as the messiah of the desert-bound guerrillas known as the Fremen. The character may be poorly conceived and just as inconsistent as it is in the novel, but MacLachlan makes us feel like cheering him on anyway, even though we’re not exactly sure what he’s up to. Likewise Kenneth McMillan as the evil Baron Harkonnen, while wearing some of the ugliest facial makeup around, makes us despise him even though we’re not exactly sure what his villainous plans are. The rest of the cast is rather fleeting in their appearances, some might say wasted: Francesca Annis, Leonardo Cimino, Brad Dourif, Jose Ferrer, Linda Hunt, Freddie Jones, Richard Jordan, Everett McGill, Jack Nance, Jurgen Prochnow, Patrick Stewart, Dean Stockwell, Max Von Sydow, Alicia Witt, Sean Young. As the Beast Rabban, Paul L. Smith speaks only thirty-four words and Sting, as Feyd-Rautha, fares a little better with only ninety words of dialogue – and that’s in the three-hour version!

Speaking of which, contrary to popular belief, Lynch made no other version of the movie besides the theatrical cut – no three-to-six hour version ever reached the post-production stage. That being said, a few slightly longer versions have been spliced together and released. Eventually, Universal approached Lynch for a possible directors cut, but declined and prefers not to discuss Dune in interviews: “Dune I didn’t have final cut on, it’s the only film I’ve made where I didn’t have. I didn’t technically have final cut on The Elephant Man (1980) but Mel Brooks gave it to me, and on Dune the film, I started selling-out even in the script phase knowing I didn’t have final cut, and I sold out, so it was a slow dying-the-death and a terrible terrible experience. I don’t know how it happened, I trusted that it would work out but it was very naive and the wrong move. In those days the maximum length they figured I could have is two hours and seventeen minutes, and that’s what the film is, so they wouldn’t lose a screening a day, so once again it’s money talking and not for the film at all and so it was like compacted and it hurt it. There is no other version. There’s more stuff, but even that is putrefied.”

Speaking of which, contrary to popular belief, Lynch made no other version of the movie besides the theatrical cut – no three-to-six hour version ever reached the post-production stage. That being said, a few slightly longer versions have been spliced together and released. Eventually, Universal approached Lynch for a possible directors cut, but declined and prefers not to discuss Dune in interviews: “Dune I didn’t have final cut on, it’s the only film I’ve made where I didn’t have. I didn’t technically have final cut on The Elephant Man (1980) but Mel Brooks gave it to me, and on Dune the film, I started selling-out even in the script phase knowing I didn’t have final cut, and I sold out, so it was a slow dying-the-death and a terrible terrible experience. I don’t know how it happened, I trusted that it would work out but it was very naive and the wrong move. In those days the maximum length they figured I could have is two hours and seventeen minutes, and that’s what the film is, so they wouldn’t lose a screening a day, so once again it’s money talking and not for the film at all and so it was like compacted and it hurt it. There is no other version. There’s more stuff, but even that is putrefied.”

Lynch disowned the extended television cut completely and chose to use the pseudonym ‘Judas Booth’ as screenwriter, a combination of Judas Iscariot and John Wilkes Booth, implying that Universal had betrayed him and killed the film. The director credit, as usual in these sorts of cases, goes to Alan Smithee (supposedly an anagram of The Alias Men, Alan Smithee has ‘directed’ over a hundred different films and television shows). Despite being considered a financial flop, Dune is the only David Lynch movie ever to make its money back in its initial box-office run, and the only one to ever break into the top five on its opening weekend. Hold that capitalistic thought while I profusely thank critic Paul Sammon and the extensive double-issue of Cinefantastique magazine September 1984 for assisting my research for this week’s review. It’s vitally important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because my horoscope said that if you don’t read all my reviews from now on, the Earth would be destroyed by a disaster of biblical proportions, you know, real wrath-of-God type stuff: Fire and brimstone coming down from the skies, rivers and seas boiling, forty years of darkness, the dead rising from the grave, human sacrifices, dogs and cats living together, earthquakes, volcanoes – you get the picture. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but I read it on the interweb, so it must be true. So sleep well and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you visiting Horror News every week! Toodles!

Lynch disowned the extended television cut completely and chose to use the pseudonym ‘Judas Booth’ as screenwriter, a combination of Judas Iscariot and John Wilkes Booth, implying that Universal had betrayed him and killed the film. The director credit, as usual in these sorts of cases, goes to Alan Smithee (supposedly an anagram of The Alias Men, Alan Smithee has ‘directed’ over a hundred different films and television shows). Despite being considered a financial flop, Dune is the only David Lynch movie ever to make its money back in its initial box-office run, and the only one to ever break into the top five on its opening weekend. Hold that capitalistic thought while I profusely thank critic Paul Sammon and the extensive double-issue of Cinefantastique magazine September 1984 for assisting my research for this week’s review. It’s vitally important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because my horoscope said that if you don’t read all my reviews from now on, the Earth would be destroyed by a disaster of biblical proportions, you know, real wrath-of-God type stuff: Fire and brimstone coming down from the skies, rivers and seas boiling, forty years of darkness, the dead rising from the grave, human sacrifices, dogs and cats living together, earthquakes, volcanoes – you get the picture. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but I read it on the interweb, so it must be true. So sleep well and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you visiting Horror News every week! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews