“A brilliant surgeon, Doctor Génessier, helped by his assistant Louise, kidnaps nice young women. He removes their faces and tries to graft them onto the head on his beloved daughter Christiane, whose face has been entirely spoiled in a car crash. All the experiments fail and the victims die, but Génessier keeps trying.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

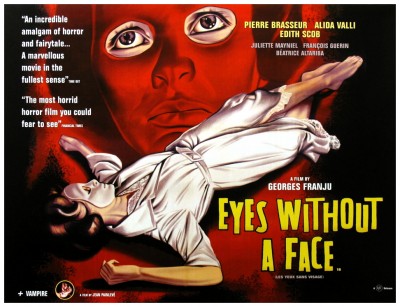

In most films dealing with the horrible things that can happen to the human body (almost invariably because of scientists doing nasty or stupid things), there used to be an unwritten law: You could show physical deformity; you could show mental anguish; but you could not show physical torment. Then along came an eccentric Frenchman who had directed a bloodcurdling documentary about abattoirs entitled The Blood Of Beasts (1949), which broke all the rules by using slaughterhouse imagery in a film about people. Eyes Without A Face (1960) directed by Georges Franju, is really too consciously artistic to be labelled simply as horror, but the American distributors decided to emphasise the sadistic aspects of the story by giving the film the frankly ridiculous title of The Horror Chamber Of Doctor Faustus.

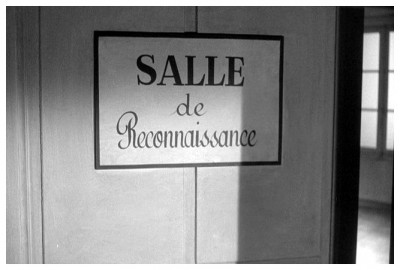

Eyes Without A Face does, in a sense, fall into one familiar category: The obsessed surgeon movie, from The Island Of Lost Souls (1932) and Mad Love (1935), to modern terrors such as The Human Centipede (2009) films. All such movies play in a remote sort of way on our fear of the surgeon’s knife, but Franju, in a convincingly clinical sequence, went one step further and actually showed the surgeon operating. The story deals with the terrible guilt a doctor (Pierre Brasseur) feels at his daughter’s facial disfigurement in a car accident for which he was responsible. He uses his nurse (Alida Valli), who is also his lover, to decoy or kidnap beautiful women and bring them to his clinic, where he literally removes the skin from their faces and attempts to graft a new face on his daughter. The grafts do not take. Eventually the daughter collapses under the strain of all of this, retreats into madness, stabs the nurse, and releases half-crazed experimental dogs on her father, the master they hate.

Eyes Without A Face does, in a sense, fall into one familiar category: The obsessed surgeon movie, from The Island Of Lost Souls (1932) and Mad Love (1935), to modern terrors such as The Human Centipede (2009) films. All such movies play in a remote sort of way on our fear of the surgeon’s knife, but Franju, in a convincingly clinical sequence, went one step further and actually showed the surgeon operating. The story deals with the terrible guilt a doctor (Pierre Brasseur) feels at his daughter’s facial disfigurement in a car accident for which he was responsible. He uses his nurse (Alida Valli), who is also his lover, to decoy or kidnap beautiful women and bring them to his clinic, where he literally removes the skin from their faces and attempts to graft a new face on his daughter. The grafts do not take. Eventually the daughter collapses under the strain of all of this, retreats into madness, stabs the nurse, and releases half-crazed experimental dogs on her father, the master they hate.

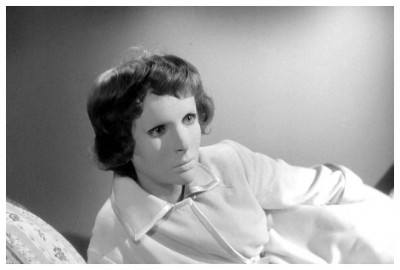

In synopsis, the film does indeed sound like a sadistic exploitation movie whose only interest today might be its adumbration of the more visceral horror which was only to enter the cinema in a widespread way a decade later. In fact, Eyes Without A Face is both more and less than this. Less, because the surgical sequences are not unbearable at all – they are executed with moderate tact with a gravely classical musical score. Nowadays far more shocking footage can be regularly viewed on television in documentaries. More, because the emotional centre of the film is not the surgery, but the wistful, haunting performance of Edith Scob as the masked daughter whose face we never see, and the delicate imagery with which she is associated.

In synopsis, the film does indeed sound like a sadistic exploitation movie whose only interest today might be its adumbration of the more visceral horror which was only to enter the cinema in a widespread way a decade later. In fact, Eyes Without A Face is both more and less than this. Less, because the surgical sequences are not unbearable at all – they are executed with moderate tact with a gravely classical musical score. Nowadays far more shocking footage can be regularly viewed on television in documentaries. More, because the emotional centre of the film is not the surgery, but the wistful, haunting performance of Edith Scob as the masked daughter whose face we never see, and the delicate imagery with which she is associated.

Edith Scob has appeared in almost a hundred different films, the most recent being the excellent Holy Motors (2012). Yes folks, this one’s still alive! Pierre Brasseur, who plays the doctor, made over 150 film and television appearances before passing away in 1972, but the performer with the most interesting career would probably be Alida Valli, who plays the nurse. By her early twenties she was already considered one of the most beautiful women in the world, and had quite a career in English language films through producer David O. Selznick who signed her to a contract, hoping he’d found another Ingrid Bergman. She appeared in several Hollywood movies, including Alfred Hitchcock‘s The Paradine Case (1947) and Carol Reed‘s The Third Man (1949) but, due to Selznick’s financial problems, she returned to Europe to star in many French and Italian films.

Edith Scob has appeared in almost a hundred different films, the most recent being the excellent Holy Motors (2012). Yes folks, this one’s still alive! Pierre Brasseur, who plays the doctor, made over 150 film and television appearances before passing away in 1972, but the performer with the most interesting career would probably be Alida Valli, who plays the nurse. By her early twenties she was already considered one of the most beautiful women in the world, and had quite a career in English language films through producer David O. Selznick who signed her to a contract, hoping he’d found another Ingrid Bergman. She appeared in several Hollywood movies, including Alfred Hitchcock‘s The Paradine Case (1947) and Carol Reed‘s The Third Man (1949) but, due to Selznick’s financial problems, she returned to Europe to star in many French and Italian films.

Valli had great success in a melodrama called Senso (1954) directed by Luchino Visconti, in which she played a Venetian Countess torn between nationalistic feelings and an adulterous love for an Austrian officer played by Farley Granger. Following Eyes Without A Face, she worked with some of the most famous directors in Europe, including Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento, leading up to her final film role in Semana Santa (2002) with Mira Sorvino. In Italy she was also well known for her stage appearances in such plays as Rosmersholm, Henry IV, Epitaph For George Dillon, A View From A Bridge and, in 1997, she obtained the Lifetime Golden Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival for her extensive career.

Valli had great success in a melodrama called Senso (1954) directed by Luchino Visconti, in which she played a Venetian Countess torn between nationalistic feelings and an adulterous love for an Austrian officer played by Farley Granger. Following Eyes Without A Face, she worked with some of the most famous directors in Europe, including Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento, leading up to her final film role in Semana Santa (2002) with Mira Sorvino. In Italy she was also well known for her stage appearances in such plays as Rosmersholm, Henry IV, Epitaph For George Dillon, A View From A Bridge and, in 1997, she obtained the Lifetime Golden Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival for her extensive career.

For his production staff, Franju enlisted people with whom he had previously worked on earlier projects. Cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, best remembered for developing the Schüfftan process and his work on Metropolis (1926), was chosen to render the visuals of the film. Schüfftan had worked with Franju on Head Against The Wall (1959), and was the ideal choice to illustrate Franju’s nightmares. Two years later, Shüfftan won the Oscar for Best Black-And-White Photography for his work on The Hustler (1961). French composer Maurice Jarre created the haunting score for the film, and had also previously worked with Franju on Head Against The Wall. Jarre subsequently wrote the soundtracks for David Lean epics such as Lawrence Of Arabia (1962), Doctor Zhivago (1965), A Passage To India (1984) and others.

For his production staff, Franju enlisted people with whom he had previously worked on earlier projects. Cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, best remembered for developing the Schüfftan process and his work on Metropolis (1926), was chosen to render the visuals of the film. Schüfftan had worked with Franju on Head Against The Wall (1959), and was the ideal choice to illustrate Franju’s nightmares. Two years later, Shüfftan won the Oscar for Best Black-And-White Photography for his work on The Hustler (1961). French composer Maurice Jarre created the haunting score for the film, and had also previously worked with Franju on Head Against The Wall. Jarre subsequently wrote the soundtracks for David Lean epics such as Lawrence Of Arabia (1962), Doctor Zhivago (1965), A Passage To India (1984) and others.

The film revolves around the twin poles of tenderness and cruelty – father and daughter love each other dearly – and as all good films about the horror of the body must be, it is partly about the horror of the mind. It is also a film about victims – the father as much as the daughter. It is unfortunate that, when the film has been imitated, it is its gruesomeness rather than its poetry that has been used as a model. And it’s with this sad thought in mind that I respectfully ask you to join me next week when I have the opportunity to give you a swift kick to the old brain-box with another fright-filled fear-fest from the far side of…Horror News! Toodles!

The film revolves around the twin poles of tenderness and cruelty – father and daughter love each other dearly – and as all good films about the horror of the body must be, it is partly about the horror of the mind. It is also a film about victims – the father as much as the daughter. It is unfortunate that, when the film has been imitated, it is its gruesomeness rather than its poetry that has been used as a model. And it’s with this sad thought in mind that I respectfully ask you to join me next week when I have the opportunity to give you a swift kick to the old brain-box with another fright-filled fear-fest from the far side of…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews