SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

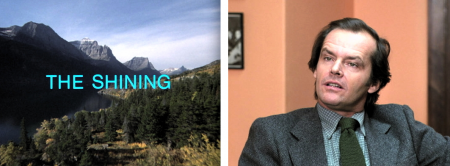

“Jack Torrance gets a job as the custodian of the Overlook Hotel, in the mountains of Colorado. The place is closed down during winter, Torrance and his family will be the only occupants of the hotel for a long while. When the snow storms block the Torrance family in the hotel, Jack’s son Danny, who has some clairvoyance and telepathy powers, discovers that the hotel is haunted and that the spirits are slowly driving Jack crazy. When Jack meets the ghost of Mr. Grady, the former custodian of the hotel who murdered his wife and his two daughters, things begin to get really nasty.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

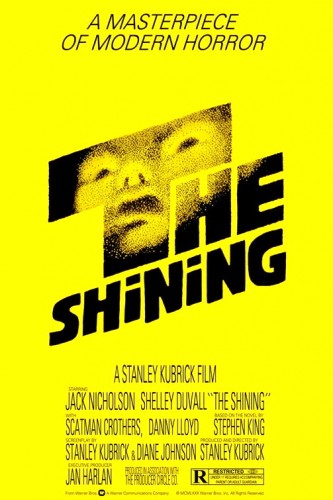

All of Stanley Kubrick‘s films seem pessimistically designed to show where humans can go wrong. A theologically-inclined critic might even argue that Kubrick’s basic subject was Original Sin. But Kubrick was not without empathy for the sinner, and he often showed us the attraction of the sin – it was one of his favourite ploys. Therefore he may not have been the most appropriate director to film Stephen King‘s novel The Shining (1980), in which ‘Evil’ exists in a remote resort hotel in the Rocky Mountains, and people are its innocent victims. In retrospect, perhaps someone like John Carpenter would have been more suitable, the filmmaker who successfully adapted King’s Christine (1983) and who regularly deals with the idea of ‘Evil’ as an external force.

Mr. King’s dissatisfaction with the film was the driving force behind the 1997 three-part miniseries adaptation of The Shining, and has been famously quoted in both Wikipedia and IMDB: “Parts of the film are chilling, charged with a relentlessly claustrophobic terror, but others fall flat. Not that religion has to be involved in horror, but a visceral skeptic such as Kubrick just couldn’t grasp the sheer inhuman evil of The Overlook Hotel. So he looked, instead, for evil in the characters and made the film into a domestic tragedy with only vaguely supernatural overtones. That was the basic flaw: because he couldn’t believe, he couldn’t make the film believable to others. What’s basically wrong with Kubrick’s version of The Shining is that it’s a film by a man who thinks too much and feels too little; and that’s why, for all its virtuoso effects, it never gets you by the throat and hangs on the way real horror should.”

All this probably accounts for the consensus view that The Shining is largely a failure. Certainly it is an uneasy film, a little more strained than most of Kubrick’s work, but there is a case for arguing that, although the film is poor King (jettisoning many of the story’s elements), it is very good Kubrick indeed. One cause of disappointment is that Kubrick shifted the emphasis from the telepathic son Danny (Danny Lloyd) to the alcoholic writer-father Jack, played with wild-eyed despair and bravado by Jack Nicholson in a performance so over-the-top as to have alienated many critics. But this fits Kubrick’s vision of the world – now the hotel becomes a metaphor for the inside of Jack’s mind, rather than just a self-sufficient chamber of horrors.

All this probably accounts for the consensus view that The Shining is largely a failure. Certainly it is an uneasy film, a little more strained than most of Kubrick’s work, but there is a case for arguing that, although the film is poor King (jettisoning many of the story’s elements), it is very good Kubrick indeed. One cause of disappointment is that Kubrick shifted the emphasis from the telepathic son Danny (Danny Lloyd) to the alcoholic writer-father Jack, played with wild-eyed despair and bravado by Jack Nicholson in a performance so over-the-top as to have alienated many critics. But this fits Kubrick’s vision of the world – now the hotel becomes a metaphor for the inside of Jack’s mind, rather than just a self-sufficient chamber of horrors.

Nevertheless, the hotel remains the centre of the vision, and Kubrick’s visual sense is as vividly in evidence as ever, as he uses a Steadicam camera to move along endless vistas of corridors and opulent rooms, occasionally inhabited by sinister children, waves of blood, creepy bartenders or decaying corpses but, more often than not, empty and echoing like Jack’s tortured mind. Aside from its other sterling qualities, the film is also the most anguished account of the psychology of writer’s block in cinematic history. Jack’s wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) is a down-to-earth matter-of-fact sort of woman, protected from the hotel’s visual phenomena until the end, though very vulnerable to the mental collapse of her husband, of which they are a symbol.

Nevertheless, the hotel remains the centre of the vision, and Kubrick’s visual sense is as vividly in evidence as ever, as he uses a Steadicam camera to move along endless vistas of corridors and opulent rooms, occasionally inhabited by sinister children, waves of blood, creepy bartenders or decaying corpses but, more often than not, empty and echoing like Jack’s tortured mind. Aside from its other sterling qualities, the film is also the most anguished account of the psychology of writer’s block in cinematic history. Jack’s wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) is a down-to-earth matter-of-fact sort of woman, protected from the hotel’s visual phenomena until the end, though very vulnerable to the mental collapse of her husband, of which they are a symbol.

Like all of Kubrick’s work, The Shining is a subtle and complex film, and it would take many thousands of words to tease out its various strands of meaning: Increasing coldness reflected in the ever-bluer film stock used; Jack as a mad Minotaur in a modern labyrinth; communications breaking down within the family, within Jack’s nonsensical manuscript, within the blizzard that isolates the hotel from the outside world. The film is definitely not a conventional horror movie, that’s for sure, and it’s public acceptance has suffered for this reason. Kubrick cut twenty-five minutes out in desperate last-minute editing before it premiered in Britain, in an effort to make the film look more conventional. However, almost contemptuously, as if to show us that he could do it if he wanted to, Kubrick puts in one superb generic horror sequence: Jack embraces a mysterious woman who emerges from a hotel bathroom, only to have her change into a rotted corpse in his arms, rather reminiscent of Nicholson’s final scene in The Terror (1963).

Like all of Kubrick’s work, The Shining is a subtle and complex film, and it would take many thousands of words to tease out its various strands of meaning: Increasing coldness reflected in the ever-bluer film stock used; Jack as a mad Minotaur in a modern labyrinth; communications breaking down within the family, within Jack’s nonsensical manuscript, within the blizzard that isolates the hotel from the outside world. The film is definitely not a conventional horror movie, that’s for sure, and it’s public acceptance has suffered for this reason. Kubrick cut twenty-five minutes out in desperate last-minute editing before it premiered in Britain, in an effort to make the film look more conventional. However, almost contemptuously, as if to show us that he could do it if he wanted to, Kubrick puts in one superb generic horror sequence: Jack embraces a mysterious woman who emerges from a hotel bathroom, only to have her change into a rotted corpse in his arms, rather reminiscent of Nicholson’s final scene in The Terror (1963).

None of Stanley Kubrick’s films have ever proved instantly accessible. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) did not pick up its vast audiences until many months had passed – it may be decades in the case of The Shining. And it’s with that thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next time when I will take you even closer to the event horizon of the insatiable black hole that is Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

A FRIGHTFUL CLASSIC ALTHOUGH IT DIFFERS ALOT FROM THE BOOK IT STILL HAS A CHILLY CHARM ALL ITS OWN