SYNOPSIS:

“In the prehistoric world, a Cro-Magnon tribe depends on an ever-burning source of fire, which eventually extinguishes. Lacking the knowledge to start a new fire, the tribe sends three warriors on a quest for more. With the tribe’s future at stake, the warriors make their way across a treacherous landscape full of hostile tribes and monstrous beasts. On their journey, they encounter Ika, a woman who has the knowledge they seek.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

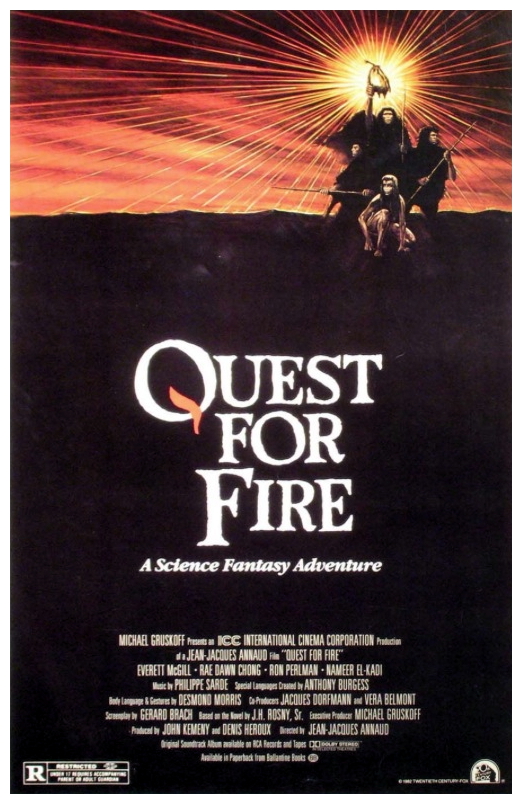

The future began 80,000 years ago when fire was primitive human’s most prized possession. We lived by it and killed for it. This US$12 million science-fantasy was the first film attempt to accurately portray the primeval world. There are plenty of films that take us into the future, but Quest For Fire (1981) takes its audience back in time to the very beginning of mankind’s existence. It is the culmination of three arduous years of preparation and exhaustive research by a large group of filmmakers led by director Jean-Jacques Annaud and producer Michael Gruskoff, whose credits include Silent Running (1972), Young Frankenstein (1974) and Werner Herzog‘s brilliant remake of Nosferatu (1979). Annuad, one of France’s most successful commercial directors, had been fascinated with the subject since his youth. He used his enthusiasm to excite screenwriter Gérard Brach, responsible for Jean de Florette (1986), The Name Of The Rose (1986), and most of Roman Polanski‘s movies.

Brach’s script was based on J.H. Rosny‘s best-selling novel The Quest For Fire, which had already sold millions of copies throughout the world and was on required reading lists for many American schools. The unusual nature and epic scope of the production were evident even during its pre-production stage. The world was scouted for locations that had never been captured on film before and were appropriate for such a journey to the past. The filmmakers ultimately chose remote parts of Canada and Scotland to recreate the waning Ice Age, and contrasting locations of blistering heat in Kenya (Iceland, Australia and New Zealand were also considered). Following a global search for unknown actors who had a talent for mime as well as the physical characteristics that would suggest early man, Ron Perlman, Everett McGill, Rae Dawn Chong and Nameer El-Kadi were chosen as the four lead roles. Perlman became famous for his roles in the television shows Beauty & The Beast and Sons Of Anarchy, and Guillermo del Toro films like Cronos (1993), Blade II (2002), Hellboy (2004) and Pacific Rim (2013). His baritone voice can also be heard in a variety of cartoons, from Batman The Animated Series to Adventure Time.

Everett McGill went on to become a character actor in films like Yanks (1979), Dune (1984), Silver Bullet (1985), Heartbreak Ridge (1986), License To Kill (1989), The People Under The Stairs (1991) and My Fellow Americans (1996), as well as appearing in both series of the cult television show Twin Peaks (1990/2017). Rae Dawn Chong, daughter of comedian Tommy Chong, went on to appear in The Colour Purple (1985), Time Runner (1993) and Commando (1985). Speaking of ‘going commando’, Chong was hired because she was completely comfortable with being naked, and remained nude on the set most of the time between scenes (while in full body makeup) to stay in character. Nameer El-Kadi changed his name to Nicholas Kadi and went on to appear in numerous television shows like JAG, Sleeper Cell, Alias, 24, ER, The Young & The Restless and The Wayans Brothers Show. Kadi met his wife on the set of Quest For Fire (she was the on-set nurse in Scotland) and Perlman is the godfather to their daughter.

Their ability to mime was particularly important because much of the drama is conveyed through gestures and a newly created language. Also required was an extraordinary capacity to endure the harshest of climates, having to perform with only the barest rudiments of clothing in freezing Canada and Scotland (Perlman and McGill both suffered frostbite) and scorching Kenya. The challenge to makeup and wardrobe artists tested the entire industry, and they rose to the occasion. Since most of the cast and a large number of extras wear prosthetics to heighten the impression of primitiveness, a small army of makeup artists had to be formed, and the problem of clothing them challenged Canada’s fur trade (the set designer caught anthrax when he handled the untreated animal skins). The personnel of the two departments, both makeup and wardrobe, numbered four dozen. Novelist-linguist Anthony Burgess is famous for devising a future language for his novel and subsequent film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange (1971): “Fire was the most revolutionary thing in all man’s history. We’re a fire-using animal and this discovery of fire was so basic to the whole progress of our race that we cannot overestimate its importance. We became a different kind of being. We became what we are now, a fire-using animal, fire in the lights around us, fire in our engines, in our jet planes and rockets.”

Utilising his enormous fund of knowledge concerning the roots of language, he fashioned a tongue similar to that probably used by our forefathers. Best-selling anthropologist Desmond Morris, author of The Naked Ape and Manwatching, created a complimentary vocabulary of gestures to support Burgess’ primitive words. “One of the notions we’re seeking to dispel in this film is the misconception that early man was a lumbering brute who was always dragging women off by the hair and living in loutish conditions. If you study the social life of primitive man from the remains we have, you discover that he could only have succeeded if there was a considerable amount of mutual aid, cooperation and love within his group. This sense of assistance, tenderness and friendship contrasted strikingly with the killing and hunting he had to do to survive. You have to show both sides to get the full picture, as we hope to do in this film.” The resulting collaboration of these two extraordinary creative consultants heightens the drama of the action-adventure by aiding understanding – even when the words spoken escape the audience, the meaning never does.

The project involved almost the entire world. Five continents were scouted, filming took place on three of them, and animals were shuffled around the world like four-legged tourists. Elephants were shifted from London to Scotland, and from Los Angeles to Ontario. Bears flew in planes and wolves howled on highways across America. By combining visual imagination with known facts about our origins, the filmmakers created an authentic portrayal of prehistoric life serving as a background for a story of action and drama. How people lived has changed considerably, but people themselves have hardly changed at all. Quest For Fire begins with the Ulam, a tribe of early Homo Sapiens who possess fire in the form of a carefully guarded small flame which they use to start larger bonfires. Driven out of their home after a bloody battle with a neanderthal tribe, the Ulam are horrified when their fire is accidentally extinguished. Because the Ulam have no idea how to create fire themselves, the tribal elder decides to send three men, Naoh (McGill), Amoukar (Perlman) and Gaw (El-Kadi), on a quest to find more fire.

The trio encounter several dangers on their quest, including a tribe of cannibals known as the Kzamm, (played by a group of professional wrestlers). The Kzamm have fire, and our heroes are determined to steal it. They lure most of the Kzamm away from their camp, kill the remaining warriors, steal their fire and prepare to head home. A young woman named Ika (Chong), who had been a captive of the Kzamm, follows them for protection. She makes a primitive poultice to help Naoh recover from his injuries, and they experience mankind’s first primitively shared emotions – laughter, sorrow, compassion and concern for one another. The four find their way to Ika’s tribe, the Ivaka, who teach them the secret of making fire. With this greatest of all accomplishments and skills, they return to the weakened Ulams and bring them the gift of life. Equally important as the fire they return with, is the new commitment between humans as shown by Naoh and Ika.

Jean-Jacques Annaud: “That is what science fantasy is all about. Nobody thinks it’s improper to fantasise about the future, so surely we are entitled to use the same technique when looking back across the millennia into the far, far distant past. Intelligent speculation, backed by research, may lead us to the truth. I needed the huge landscapes and the adventure of filming in such remote areas to enable me to get into the minds of my characters. I needed to show and to feel how these primitives dealt with their world and its dangers, when they themselves were so small and weak. I know that the toughness of the locations have helped me and my actors to experience for ourselves the great adventure of man against the elements.” Just as those special places helped Annaud and his actors, they needed the punctuation of animal life to make them come alive. This proved to be one of the most challenging aspects of bringing Quest For Fire to the screen: Indian elephants from London Zoo brought to Scotland and forced to wear huge fake tusks and a wig the size of a living-room rug; safely choreograph attacks from real bears and wolves; make a modern lion look like an extinct sabre-tooth tiger. How? Very carefully, and that can be said of all the animal-life challenges that were faced by the filmmakers.

If that wasn’t challenging enough, the majority of scenes were shot in a single take. Everything was shot live in-camera, and there are no optical effects. Quest For Fire boldly creates a world unlike any we’ve seen before, with dedicated actors going well beyond the call of duty in portraying a life and death struggle for survival under the most harrowing conditions imaginable. Featuring Claude Agostini‘s splendid wide-screen cinematography and a rich score by Phillipe Sarde, this movie will take you on a compelling journey that, if nothing else, will help you appreciate our routine creature comforts. Annaud and his collaborators tell their tale with dramatic simplicity and virtually no dialogue, but the points made are powerful. Humanity survives and will prevail despite our weaknesses and faults. Overall, a remarkable life-affirming work. And it’s with this upbeat thought in mind I’ll bid you a good night and pleasant dreams, and politely ask you to pop in again next week when I dig up another terror from beyond the bottom of the garden path for…Horror News! Toodles!

Quest For Fire (1981)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

I saw this so long ago I don’t think I appreciated the accomplishment it is. I do remember being fascinated though. Thanks for another insightful review into a film I’ll eventually revisit.

Thanks again for reading. Yes, it’s definitely worth seeing again, particularly if one has not seen it for a while, not least for Ron Perlman and Everett McGill’s first performances.