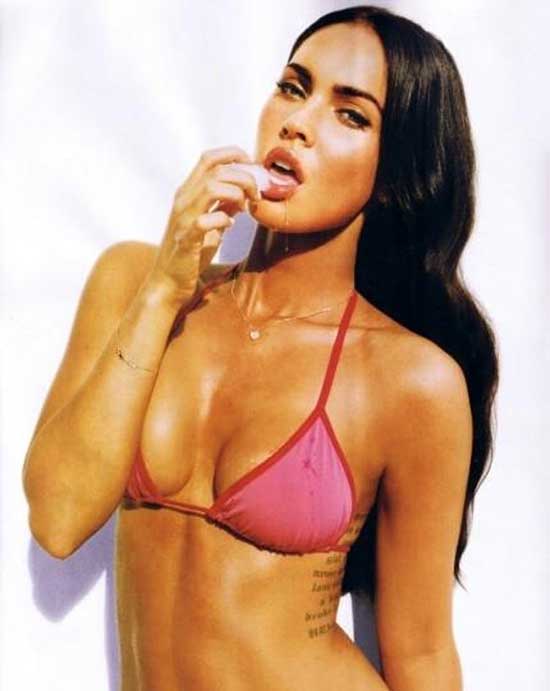

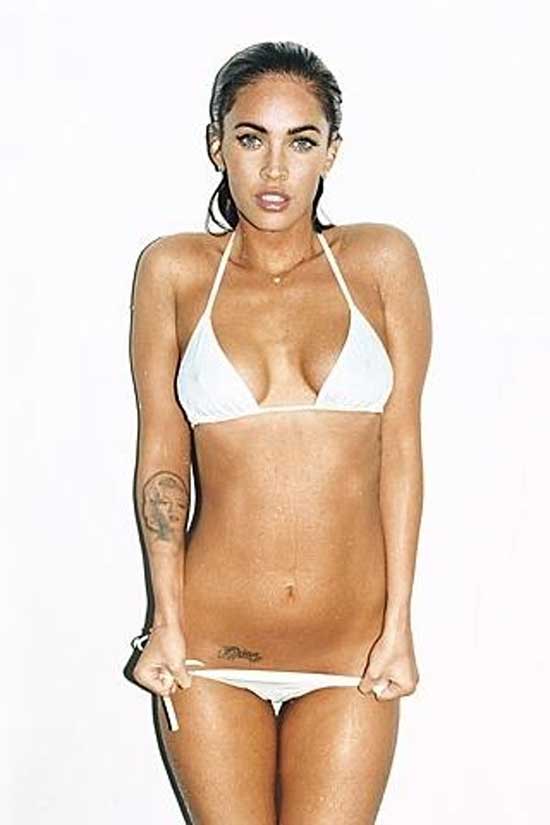

If you’ve been following our collective of hot ladies nest and sexiest images, you know sooner or later we’d have to address lovely Megan. In fact, she’s had so many photo shots taken that you’d be hard pressed not to ever come across several of them. An actress who has graced plenty of films and media attention, Megan’s contribution to the horror genre is rather limited to a small handful of features.

Her most noted in these area being 2009’s, “Jennifer’s Body“, a rather interesting film worth repeat viewings. The Science fiction film Transformers was essential to kick starting her career leaving a legacy to that film alone as a Best of Megan fox moment. Here appearance in “Jonah Hex” was limited but still inspiring as component of eye candy to the release.

I would think that more is to come as she branches out into fantasy rooted roles. In any case, this lovely gal has inspired countless stares with her almost perfect collective of modeling pics and lingerie photos. Thus leading us to a very rich collection of sexy photographs. Welcome to our hottest sexiest photo collection of Megan Fox. Of course, there are more where this came from, see our sexiest photos collections. Enjoy the gallery, its as good as getting a free bonus

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

![True_Blood_Jessica_Fangs_by_Morgadu[1]](https://horrornews.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/True_Blood_Jessica_Fangs_by_Morgadu1-310x165.jpg)