SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

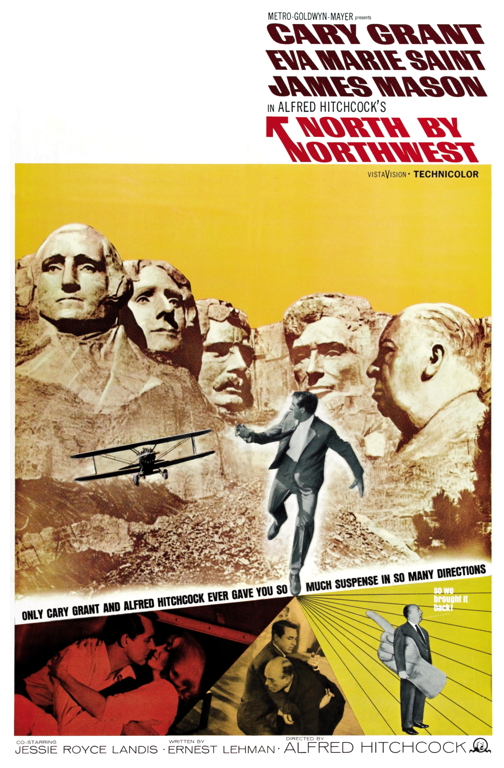

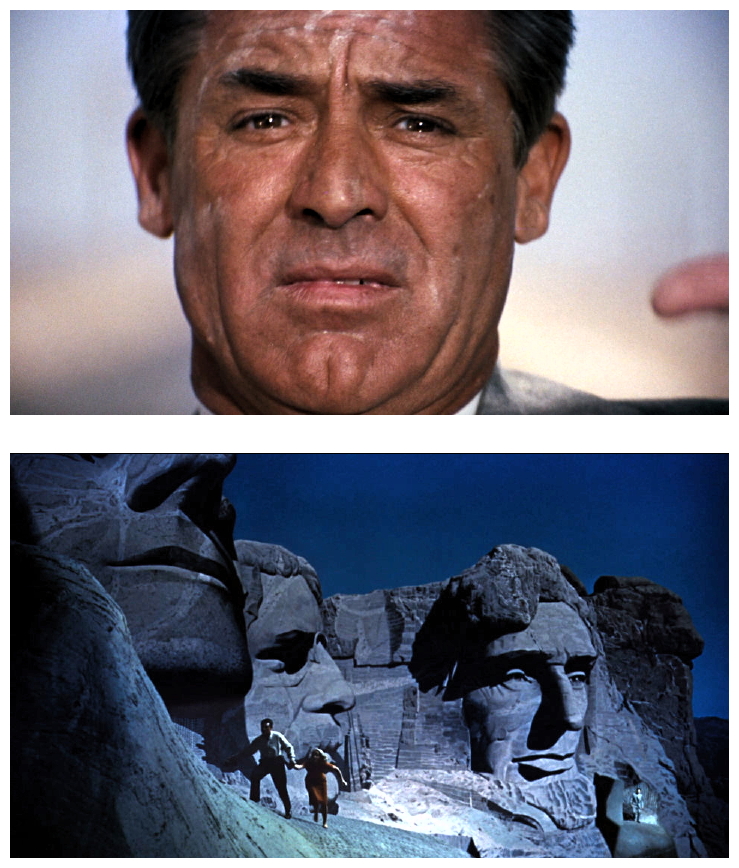

“Madison Avenue advertising man Roger Thornhill finds himself thrust into the world of spies when he is mistaken for a man by the name of George Kaplan. Foreign spy Philip Vandamm and his henchman Leonard try to eliminate him but when Thornhill tries to make sense of the case, he is framed for murder. Now on the run from the police, he manages to board the 20th Century Limited bound for Chicago where he meets a beautiful blond, Eve Kendall, who helps him to evade the authorities. His world is turned upside down yet again when he learns that Eve isn’t the innocent bystander he thought she was. Not all is as it seems however, leading to a dramatic rescue and escape at the top of Mount Rushmore.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

It is impossible for anyone who has seen even one of his films to deny Alfred Hitchcock his place inside the cinema’s pantheon of greats, for his was the most ‘cinematic’ mind of all and, at the same time, the most isolated from ‘real life’ of all the great directors. Cinema made Hitchcock just as surely as the stage made Laurence Olivier, and he was equally in thrall to it, allowing his unconscious mind – and ours – to its magic. He worked in England until 1939, turning out a series of bravura films including The 39 Steps (1935), Young And Innocent (1937) and The Lady Vanishes (1938) and then, as if he instinctively understood how World War Two would work out, he moved to the United States, where he began work on a new series of films.

These proved unique in the annals of commercial cinema in that they successfully spanned the two worlds of the critically acclaimed and the financially viable over the immense period of thirty-six years. Rebecca (1940), Suspicion (1941) and Saboteur (1942) initially harked back to his English years but, with Spellbound (1945), he discovered his lodestone, namely the American film with English sensibilities, and this was to become his stock-in-trade during the remainder of his career. Notorious (1946), Strangers On A Train (1951), Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958). His next film, North By Northwest (1959), was to be his final remake of The 39 Steps (1935), that is to say the film in which an innocent uninvolved hero is suddenly caught up with extraordinary events and chased across vast swathes of countryside, while intent on tracking down the rightful villains in order to re-establish his reputation, and to consummate his relationship with the blonde he has picked up along the way.

These proved unique in the annals of commercial cinema in that they successfully spanned the two worlds of the critically acclaimed and the financially viable over the immense period of thirty-six years. Rebecca (1940), Suspicion (1941) and Saboteur (1942) initially harked back to his English years but, with Spellbound (1945), he discovered his lodestone, namely the American film with English sensibilities, and this was to become his stock-in-trade during the remainder of his career. Notorious (1946), Strangers On A Train (1951), Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958). His next film, North By Northwest (1959), was to be his final remake of The 39 Steps (1935), that is to say the film in which an innocent uninvolved hero is suddenly caught up with extraordinary events and chased across vast swathes of countryside, while intent on tracking down the rightful villains in order to re-establish his reputation, and to consummate his relationship with the blonde he has picked up along the way.

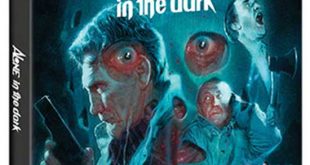

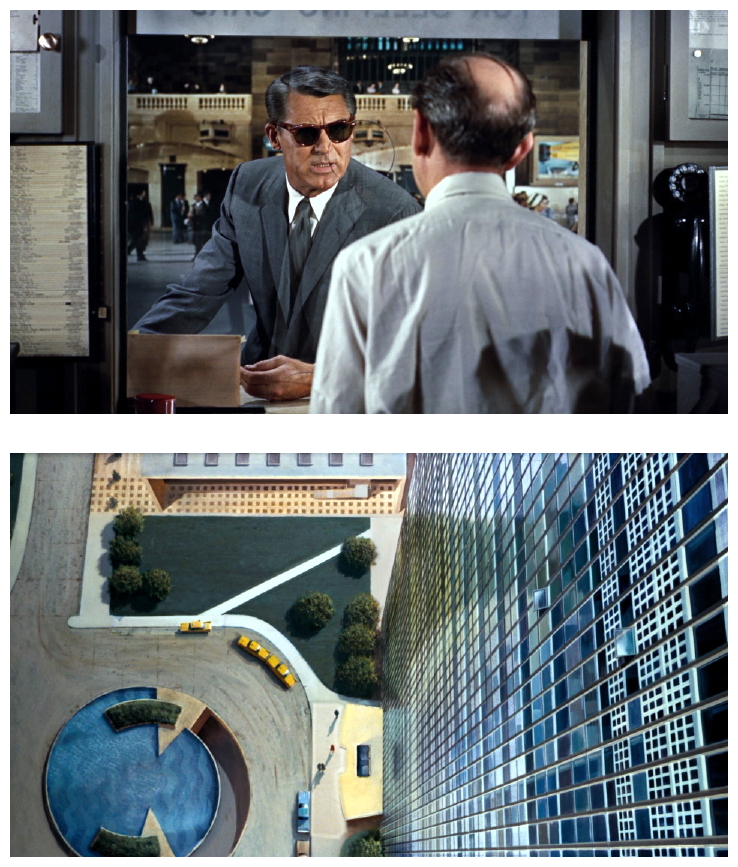

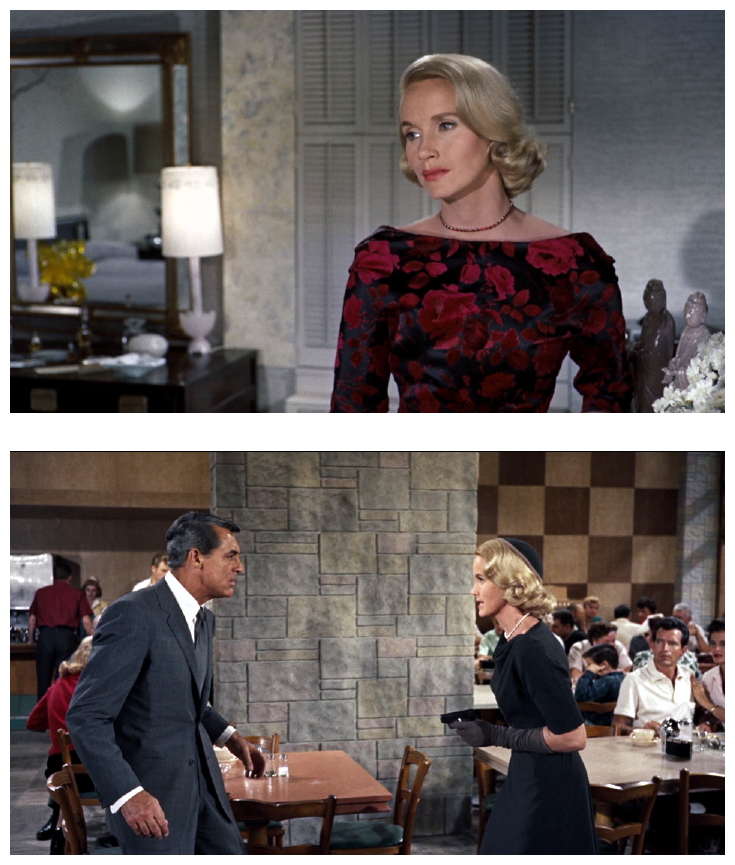

As a formula Hitchcock never made it work so well as in North By Northwest, his backdrop the vastness of the American landscape, the climax taking place on the carved faces of Mount Rushmore, under the friendly eyes of old presidents. Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) is a New York advertising executive who, while at a smart lunch with his mother (Jessie Royce Landis), accidentally answers a call for one George Kaplan. From this point, Thornhill is drawn into a nightmare of mistaken identity which links him up with glamorous Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), pitches him against the velvety Vandamm (James Mason) and propels him like a pinball across the country, involving him in accusations of murder and spying, seeing him attacked by an anonymous aerial dust-cropper, and finally fetching him up Mount Rushmore.

As a formula Hitchcock never made it work so well as in North By Northwest, his backdrop the vastness of the American landscape, the climax taking place on the carved faces of Mount Rushmore, under the friendly eyes of old presidents. Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) is a New York advertising executive who, while at a smart lunch with his mother (Jessie Royce Landis), accidentally answers a call for one George Kaplan. From this point, Thornhill is drawn into a nightmare of mistaken identity which links him up with glamorous Eve Kendall (Eva Marie Saint), pitches him against the velvety Vandamm (James Mason) and propels him like a pinball across the country, involving him in accusations of murder and spying, seeing him attacked by an anonymous aerial dust-cropper, and finally fetching him up Mount Rushmore.

Who is after him? The mysterious Professor (Leo G. Carroll) finally answers the question: Everyone apparently, the police, US Intelligence and Russian agents. An attempt to break into Vandamm’s extraordinarily modernist cliff-top lair finds Eve and Roger scaling the rock-faces of various American presidents, pursued by Vandamm’s thugs, among them Leonard (Martin Landau), one of the first homosexual assassins in the history of cinema (although there is nothing in the script saying so, Landau was instructed by Hitchcock to play Leonard as a gay man). In one sequence there is an assassination at the United Nations building in New York and in another, probably one of the most famous scenes in any Hitchcock movie, Cary Grant is strafed by a low-flying crop-dusting plane in the middle of an open prairie.

Who is after him? The mysterious Professor (Leo G. Carroll) finally answers the question: Everyone apparently, the police, US Intelligence and Russian agents. An attempt to break into Vandamm’s extraordinarily modernist cliff-top lair finds Eve and Roger scaling the rock-faces of various American presidents, pursued by Vandamm’s thugs, among them Leonard (Martin Landau), one of the first homosexual assassins in the history of cinema (although there is nothing in the script saying so, Landau was instructed by Hitchcock to play Leonard as a gay man). In one sequence there is an assassination at the United Nations building in New York and in another, probably one of the most famous scenes in any Hitchcock movie, Cary Grant is strafed by a low-flying crop-dusting plane in the middle of an open prairie.

To create this astonishing piece of cinema, Hitchcock deliberately stood the cliche on its end by choosing the most open, exposed and unlikely setting for an ambush, a place far removed from the traditional dark alleyways, gleaming cobblestones and hidden doorways of orthodox skulduggery. The screenplay by Ernest Lehman was an original, not adapted from a novel or play, and is a model of suspense screenwriting, even if the plot becomes rather incomprehensible almost from the get-go. The ‘McGuffin’ is shrugged off in the best Hitchcockian manner: Leo G. Carroll is actually a blase intelligence chief who refuses to specify his exact agency by saying: “FBI, CIA, ONI, we’re all in the same alphabet soup,” while James Mason‘s villainy is explained in the simple statement that his men are after government secrets.

To create this astonishing piece of cinema, Hitchcock deliberately stood the cliche on its end by choosing the most open, exposed and unlikely setting for an ambush, a place far removed from the traditional dark alleyways, gleaming cobblestones and hidden doorways of orthodox skulduggery. The screenplay by Ernest Lehman was an original, not adapted from a novel or play, and is a model of suspense screenwriting, even if the plot becomes rather incomprehensible almost from the get-go. The ‘McGuffin’ is shrugged off in the best Hitchcockian manner: Leo G. Carroll is actually a blase intelligence chief who refuses to specify his exact agency by saying: “FBI, CIA, ONI, we’re all in the same alphabet soup,” while James Mason‘s villainy is explained in the simple statement that his men are after government secrets.

None of it matters anyway, for the film is superb fast-moving entertainment from start to finish, shot with a polished assurance, rich in humour and irony as well as menace and excitement. It is a fitting final word on the chase theme, and a perfect summation of Hitchcock’s experience in making this kind of movie. North By Northwest boasts outstanding performances, technical brilliance, a great deal of humour, stunning photography by Robert Burks, one of Bernard Herrmann‘s finest scores, nifty titles by Saul Bass, terrific locations for suspenseful sequences, and a great deal of sex is provided by Eva Marie Saint‘s cool-but-lustful character. There are some kisses between Grant and Saint (as the camera spins around them) that must have driven the censorship board to distraction.

None of it matters anyway, for the film is superb fast-moving entertainment from start to finish, shot with a polished assurance, rich in humour and irony as well as menace and excitement. It is a fitting final word on the chase theme, and a perfect summation of Hitchcock’s experience in making this kind of movie. North By Northwest boasts outstanding performances, technical brilliance, a great deal of humour, stunning photography by Robert Burks, one of Bernard Herrmann‘s finest scores, nifty titles by Saul Bass, terrific locations for suspenseful sequences, and a great deal of sex is provided by Eva Marie Saint‘s cool-but-lustful character. There are some kisses between Grant and Saint (as the camera spins around them) that must have driven the censorship board to distraction.

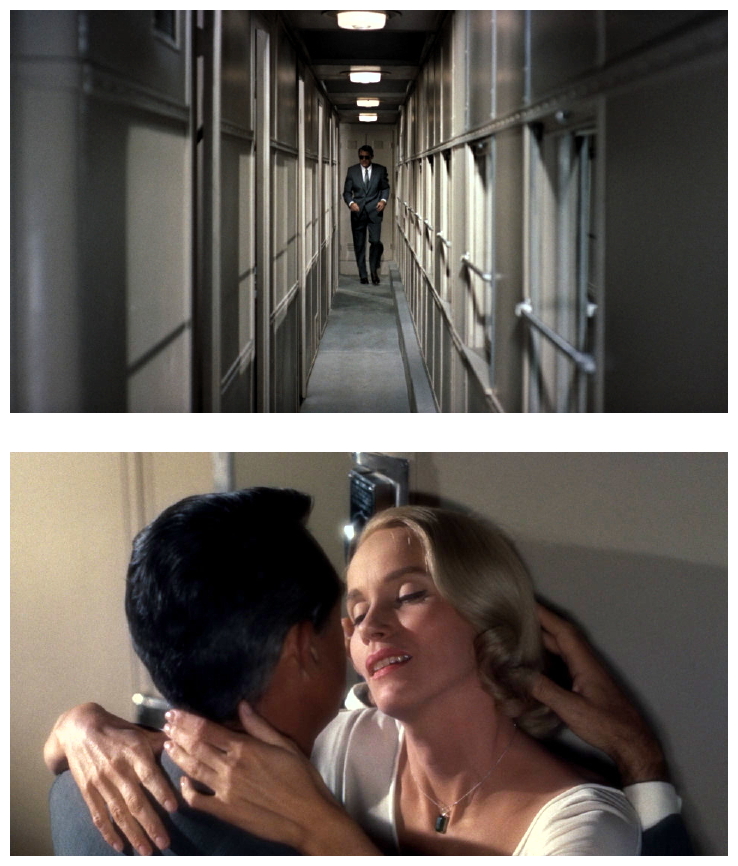

While the classic crop-dusting and cliff-hanging scenes are the most exciting moments, Hitchcock’s greatest accomplishment was to keep the film moving at a decent pace for 136 minutes. He does this by not only having his characters move quickly from one locale to another, but by having movement within the frame and showing all types of transportation vehicles in motion – taxis, cars, police vehicles, buses, trains, trucks and planes. In many ways the film can be easily thought of as the prototype James Bond adventure due to its similarities with colourful settings, secret agents and an elegant, daring, wisecracking leading man opposite a sinister yet strangely charming villain. In fact the crop-duster scene was the primary inspiration behind the helicopter chase in From Russia With Love (1963). Hitchcock’s on-screen relationship with Cary Grant was one of his most fruitful. Hitchcock could see the potentially perverse core at the heart of Grant’s light-hearted quipping screen persona.

While the classic crop-dusting and cliff-hanging scenes are the most exciting moments, Hitchcock’s greatest accomplishment was to keep the film moving at a decent pace for 136 minutes. He does this by not only having his characters move quickly from one locale to another, but by having movement within the frame and showing all types of transportation vehicles in motion – taxis, cars, police vehicles, buses, trains, trucks and planes. In many ways the film can be easily thought of as the prototype James Bond adventure due to its similarities with colourful settings, secret agents and an elegant, daring, wisecracking leading man opposite a sinister yet strangely charming villain. In fact the crop-duster scene was the primary inspiration behind the helicopter chase in From Russia With Love (1963). Hitchcock’s on-screen relationship with Cary Grant was one of his most fruitful. Hitchcock could see the potentially perverse core at the heart of Grant’s light-hearted quipping screen persona.

He had cast Grant as the suave but possibly murderous husband of Joan Fontaine in Suspicion (1941), as the manipulative intelligence man putting Ingrid Bergman through hell in Notorious (1946), and as an improbable Monte Carlo cat-burglar charming Grace Kelly in To Catch A Thief (1955). In North By Northwest Hitchcock turned the tables, this time putting Grant through the mill, but rewarding him with (as Hitch insisted) the first mainstream filming of sexual intercourse: After a prolonged lingering kiss, the escaping lovers’ train plunges into a tunnel. I’ll now leave you with this sexy image in mind, but not before reminding you to please join me again next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the land of Movie Magic for…Horror News. Toodles!

He had cast Grant as the suave but possibly murderous husband of Joan Fontaine in Suspicion (1941), as the manipulative intelligence man putting Ingrid Bergman through hell in Notorious (1946), and as an improbable Monte Carlo cat-burglar charming Grace Kelly in To Catch A Thief (1955). In North By Northwest Hitchcock turned the tables, this time putting Grant through the mill, but rewarding him with (as Hitch insisted) the first mainstream filming of sexual intercourse: After a prolonged lingering kiss, the escaping lovers’ train plunges into a tunnel. I’ll now leave you with this sexy image in mind, but not before reminding you to please join me again next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the land of Movie Magic for…Horror News. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews