SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Recovering from an attempted suicide, a man is selected to participate in a time travel experiment that has only been tested on mice. A malfunction in the experiment causes the man to experience moments from his past in a random order.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

For most of the sixties, genre cinema had been going through a very quiet period and, incidentally, not making any money for the major studios either. Of the few real hits in fantastic films between 1960 and 1967, most were on the fringe at best. The major commercial successes were Doctor No (1962), The Birds (1963), Doctor Strangelove (1964), Mary Poppins (1964) and You Only Live Twice (1967). Apart from Mary Poppins’ ability to levitate, there wasn’t much in the way of hardcore supernatural or science fiction effects in any of these. But everything was to change in 1968, the year of the big breakthrough. Curiously enough, the first signs of a renewed interest in genre cinema came from France rather than from Hollywood.

Fantasy had always been popular with French intellectuals, and it was one of the most intellectual of New Wave film directors who surprised the world by showing that science fiction scenarios could be taken seriously by so-called ‘artistic’ filmmakers. French filmmaker Alain Resnais passed away in March earlier this year, after an extensive career of more than six decades. After training as an editor during the forties, he went on to direct a number of short films like Night And Fog (1955), a groundbreaking documentary concerning Nazi concentration camps. By the late fifties Resnais was making feature films and established his reputation with Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), Last Year At Marienbad (1961) and Muriel (1963), all of which adopted unconventional narrative techniques to deal with themes of troubled memory and the imagined past.

Fantasy had always been popular with French intellectuals, and it was one of the most intellectual of New Wave film directors who surprised the world by showing that science fiction scenarios could be taken seriously by so-called ‘artistic’ filmmakers. French filmmaker Alain Resnais passed away in March earlier this year, after an extensive career of more than six decades. After training as an editor during the forties, he went on to direct a number of short films like Night And Fog (1955), a groundbreaking documentary concerning Nazi concentration camps. By the late fifties Resnais was making feature films and established his reputation with Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959), Last Year At Marienbad (1961) and Muriel (1963), all of which adopted unconventional narrative techniques to deal with themes of troubled memory and the imagined past.

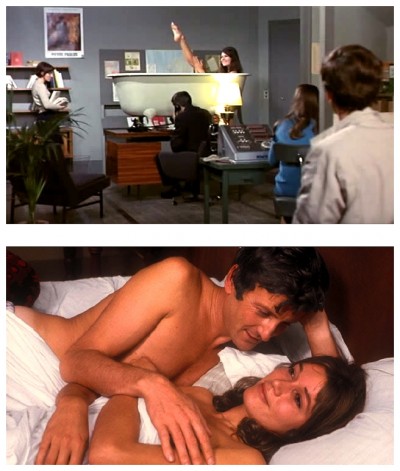

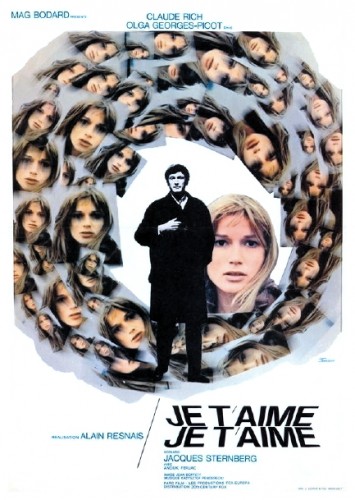

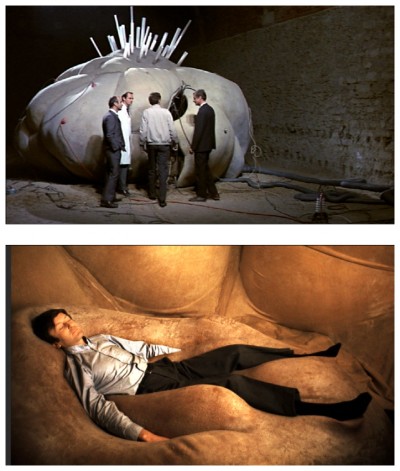

Je t’aime, Je t’aime (1968) puzzled the intellectuals, for here Resnais and his screenwriter Jacques Sterberg had moved from the subjective use of time travel via memories (as in Last Year At Marienbad) to the actual use of a bona-fide science fiction time machine. Looking like a cross between a womb and a pumpkin, it is a very organic time machine indeed. A young man named Claude Ridder (Claude Rich), who recently failed an attempt at suicide, is discharged from hospital, only to be abducted by a group of scientists who want him to take part in a medical experiment, and go back into his own past.

Je t’aime, Je t’aime (1968) puzzled the intellectuals, for here Resnais and his screenwriter Jacques Sterberg had moved from the subjective use of time travel via memories (as in Last Year At Marienbad) to the actual use of a bona-fide science fiction time machine. Looking like a cross between a womb and a pumpkin, it is a very organic time machine indeed. A young man named Claude Ridder (Claude Rich), who recently failed an attempt at suicide, is discharged from hospital, only to be abducted by a group of scientists who want him to take part in a medical experiment, and go back into his own past.

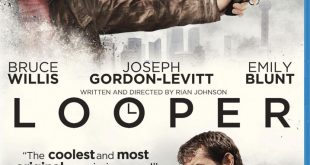

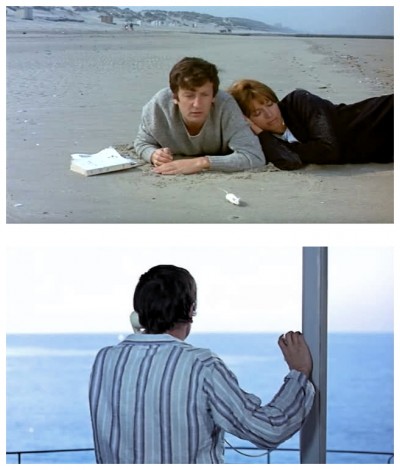

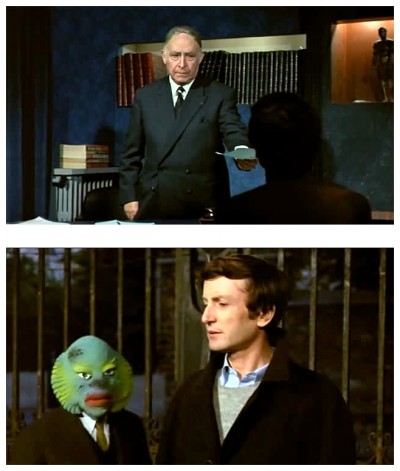

Unfortunately the machine malfunctions and he begins to oscillate back and forth in time. But does the soft womb-like time machine bring about a rebirth or a miscarriage? The first part of the trip is to the warm amniotic fluid of the sea and to a love affair. Thereafter it becomes rather difficult to distinguish between ‘actual’ events and desired or hallucinated events, not unlike the extraordinary novels of Philip K. Dick. The remainder of the film consists of fragments of his previous life – presented by Resnais in the deliberately disorientating Last Year At Marienbad style – that slowly build up to produce a picture of humdrum monotony as well as a suspicion that he may have murdered his dreary girlfriend (Olga Georges-Picot). This a very moving but rather unhappy film, although it has some good jokes too, like when the time-traveling hero enters a telephone booth to dial TIME, suggesting that the paradoxes of time are difficult to cope with, and that the past may not be easily changed.

Unfortunately the machine malfunctions and he begins to oscillate back and forth in time. But does the soft womb-like time machine bring about a rebirth or a miscarriage? The first part of the trip is to the warm amniotic fluid of the sea and to a love affair. Thereafter it becomes rather difficult to distinguish between ‘actual’ events and desired or hallucinated events, not unlike the extraordinary novels of Philip K. Dick. The remainder of the film consists of fragments of his previous life – presented by Resnais in the deliberately disorientating Last Year At Marienbad style – that slowly build up to produce a picture of humdrum monotony as well as a suspicion that he may have murdered his dreary girlfriend (Olga Georges-Picot). This a very moving but rather unhappy film, although it has some good jokes too, like when the time-traveling hero enters a telephone booth to dial TIME, suggesting that the paradoxes of time are difficult to cope with, and that the past may not be easily changed.

Yet some changes may be possible – the film ends with another attempt at suicide by the protagonist, the implication being that this time he succeeds. Keep an eye out (ow!) for the white laboratory mouse during the last minutes of the film, one of the saddest and most resonant closing scenes in genre cinema. Je t’aime, Je t’aime or I Love You, I Love You (the repetition of the phrase has a subtle meaning in the film) is a breakthrough movie because of its intrinsic quality, not because it was a smash hit. Indeed, it was not released in the United Kingdom until 1971: the film was listed to compete at the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, but the festival was cancelled that year due to countrywide strikes. When it was eventually released, it was dismissed by influential movie critic Penelope Gilliatt largely on account of the alleged unattractiveness of Claude Rich‘s legs!

Yet some changes may be possible – the film ends with another attempt at suicide by the protagonist, the implication being that this time he succeeds. Keep an eye out (ow!) for the white laboratory mouse during the last minutes of the film, one of the saddest and most resonant closing scenes in genre cinema. Je t’aime, Je t’aime or I Love You, I Love You (the repetition of the phrase has a subtle meaning in the film) is a breakthrough movie because of its intrinsic quality, not because it was a smash hit. Indeed, it was not released in the United Kingdom until 1971: the film was listed to compete at the 1968 Cannes Film Festival, but the festival was cancelled that year due to countrywide strikes. When it was eventually released, it was dismissed by influential movie critic Penelope Gilliatt largely on account of the alleged unattractiveness of Claude Rich‘s legs!

Time and memory have always been the two principal themes of Alain Resnais‘s work, certainly his earlier films, which he described as attempts, however imperfect, to approach the complexity of thought and its mechanism: “I prefer to speak of the imaginary, or of consciousness. What interests me in the mind is that faculty we have to imagine what is going to happen in our heads, or to remember what has happened.” It’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations ever to be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Time and memory have always been the two principal themes of Alain Resnais‘s work, certainly his earlier films, which he described as attempts, however imperfect, to approach the complexity of thought and its mechanism: “I prefer to speak of the imaginary, or of consciousness. What interests me in the mind is that faculty we have to imagine what is going to happen in our heads, or to remember what has happened.” It’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I have the opportunity to present you with more unthinkable realities and unbelievable factoids of the darkest days of cinema, exposing the most daring shriek-and-shudder shock sensations ever to be found in the steaming cesspit known as…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews