On a trip home to visit her father, Jenny is thrown into a world of mystery, horror and legend when she is called upon by 3000 year old spirits of the Neverlake to help return their lost artifacts and save the lives of missing children.

REVIEW:

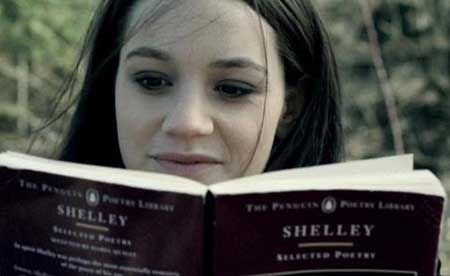

Neverlake opens poetically to correlate with its poetic introduction. A young, dark-haired girl floats lifelessly while submerged in water; she’s dressed in a white-laced gown ripped straight from the pages of a Victorian novel. Over the fantastic imagery, the narration begins, and we first hear protagonist Jenny’s voice—sharply British—recite a haunting poem by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Allegedly inspired by his poem, “The Sensitive Plant,” Shelley’s lines saturate a large portion of the film, bringing with it its dreamy thematic strain. This plot device works well in frosting the film with a taste of originality. However, though this earns Neverlake positive points, it also conflicts with the various genres squished into one collaborative piece the makers dub a “horror film.”

The makers’ effort does merit some admiration—whether the genre collision works, remains ambivalent. Besides this factor, other distressing variables dampen the Romantic glamour of the movie. To start, many connections fail to happen. For instance, Jenny states in the beginning that she was born from British parents in Tuscany. Since then, she had not returned to Italy, but instead lived in America attending school subsequent to the death of her mother due to an unnamed illness. Then, why does Jenny possess a thick English accent? This goes unexplained. Carrying a carefree and jovial demeanor, Jenny rides a train to meet her father, whom inexplicably summons her after undergoing puberty.

From the very moment Jenny arrives at her perpetually frowning father’s estate, an ominous feeling pervades—this feeling only intensifies with the progression of the film, adding to the cacophony of genres, an air of mystery. Her father introduces her to his friend and “housekeeper,” Olga, another perpetually frowning figure. It is revealed that Jenny’s father, Dr. Brook, is an archeologist studying the ancient Etruscans and a mysterious “healing lake” worshipped by them—a lake also conveniently located right next to his estate.

Since Jenny’s cold reception, her father neglects to spend any time with her, frequently slipping out to do unknown errands in the neighboring town of Arettzo. He orders even colder Olga to feed Jenny unidentifiable capsules Olga awkwardly calls “v-tah-mens,” which Jenny happily swallows with no questions asked. The undeniable Dahmer vibe amplifies from one moment to the next with a strange sensation of constant voyeurism. Aside from running errands, Jenny’s father largely leaves her to herself; when present, he locks himself in his study, ordering Olga to tell Jenny not to disturb him. His attitude towards his daughter reflects one of apathy and suppressed irritation.

Bored, naturally, Jenny slips out to the mythical lake which eerily sits under a thick layer of fog, seemingly frozen in dubious enchantment. There, she meets a girl blindfolded with an old rag. The color in her face and clothes, faded, creates the iconic image of a child-like ghost. She asks Jenny to accompany her to her home, an orphanage that appears more like a deteriorated asylum. To add to the sinister quality emphasized here, the blind girl tells Jenny to avoid the eyes of “adults” because “they’re bad.” Once inside, things start to quickly resemble a collision of Halloween meets The Chronicles of Narnia.

Jenny meets other sickly, faded, ghost-like children, each with his or her own unique malady. But it’s the way these grotesque characters unearth that laces the gothic with a bit of Romantic fantasy—the music, their innocence, the way Jenny returns to read to them every day, and the mission they deliver her. It seems incongruous, romanticized naivety amidst medical horror, confusing the audience as to the main purpose and actual genre of the film. It certainly merits the title of genre-bender.

Images of Jenny reciting poetry and Shakespeare to morbidly whimsical children juxtapose scenes of her awaking in recovery of a medical procedure she cannot remember. Combine this with nightmare sequences filled with ancient lake monsters. Somewhere in this whirlwind of themes lies the true villain—Dr. Brook. After Jenny retrieves idols at the bottom of the lake that symbolize body parts and organs, the ghost children’s identities are revealed, and Jenny’s mother is found.

Dr. Brook, with the help of Olga, secretly harvested Dr. Brook’s children by women he impregnated with one sole purpose—to consistently replace their love child (Maya)’s failing parts. Jenny finds her captive mother a prisoner of her maniacal father, and the ghosts of the organ-harvested children manifest (which Jenny’s mother reveals are her brothers and sisters). One small problem pops up—if it started with Jenny’s mother, then why does Peter look older than Jenny? This exemplifies another instance of connections failing to happen.

It ends as it begins—with Percy Bysshe Shelley—coming full circle, and committing to its Romantic horror. Not a masterpiece, but worth a look for the sake of its intriguing hint of originality, an unfortunately rare trait in contemporary horror.

Neverlake is coming soon on DVD per Uncork’d Entertainment

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Great review, Caitlin! Keep it up, enjoyed your last one too!

Thanks Andrew!

This is a spot on review for the movie I just watched.

It was definitely a strange blend. I didn’t mind the blend, I just wished the plot wrinkles and the flow of the film would’ve been ironed out a bit. I thought the main character was charming.

I too am having problems understanding peters age in this, but I can explain the English accent (because I was surprised enough by the ending I restarted it and watched it through again.) Jenny says that she was first sent to live with her grandma rose, who hated her father for some reason, before grandma went senile and THEN she went to American boarding school.

What’s haunting me is, did the father allow the chained mother to birth and lovingly raise each baby in that abandoned room until they were harvested?? That would explain all the broken toys. But man, that…that’s the most terrible part of this film if true.

Thanks for writing up such a thoughtful review of this. It deserved one.

From my understanding of the movie, the children had different mothers.

Couple of question’s about Jenny.

Why did the father let her go to the grandmother? To play up Jenny’s mothers’ death to keep her chained up? And I am assuming Jenny’s parents, at some point, were involved, because how else would the grandmother not care for the father???

Just so as ya know, “vih – tah – mens” is just the way British people (and several other cultures) pronounce the word ‘vitamins’ (vie- tah- mens), as an American would do. I love this movie. Wish there were some further explanations behind some of the themes.