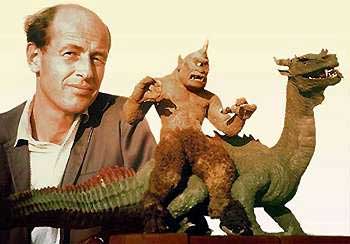

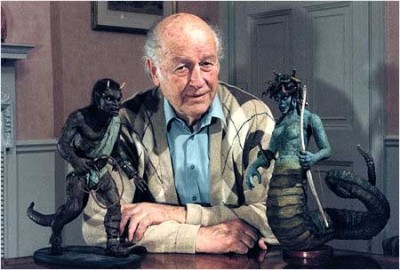

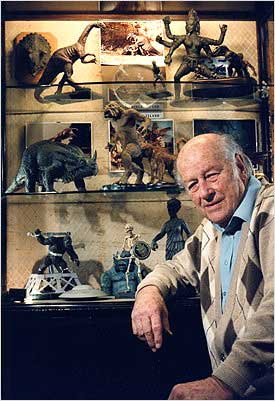

The most famous animated creature in film history was King Kong (1933), built and manipulated by Willis O’Brien. A decade later O’Brien was working on another giant ape movie called Mighty Joe Young (1946) and hired a young assistant, Ray Harryhausen. During the fifties it became clear that Harryhausen had inherited O’Brien’s mantle as the top stop-motion animator in the film business, a position which, in the eyes of many, he continues to hold. Stop-motion animation is done by photographing models one frame at a time to give the illusion that they are in motion when the film is played back (the models are normally constructed around flexible armatures), and then optically combining the results with live action, often using a technique known as the traveling matte. When live action is combined with the animated miniature, tricks can be played with scale, so that a model less than a foot tall can appear to loom up like a colossus.

The most famous animated creature in film history was King Kong (1933), built and manipulated by Willis O’Brien. A decade later O’Brien was working on another giant ape movie called Mighty Joe Young (1946) and hired a young assistant, Ray Harryhausen. During the fifties it became clear that Harryhausen had inherited O’Brien’s mantle as the top stop-motion animator in the film business, a position which, in the eyes of many, he continues to hold. Stop-motion animation is done by photographing models one frame at a time to give the illusion that they are in motion when the film is played back (the models are normally constructed around flexible armatures), and then optically combining the results with live action, often using a technique known as the traveling matte. When live action is combined with the animated miniature, tricks can be played with scale, so that a model less than a foot tall can appear to loom up like a colossus.

O’Brien, who passed away in 1962, lived long enough to see some of his former pupil’s success, though most of the early films on which Harryhausen worked were comparatively minor: The seminal Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and Twenty Million Miles To Earth (1957). But in the late fifties Harryhausen, along with the producer with whom he nearly always worked, Charles Schneer, had a breakthrough film, The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad (1958). Very much an exotic fairy-tale largely aimed at children, but with a love interest as well, it turned out to appeal to children of all ages. The time was obviously ripe for this sort of romantic fabled based loosely on traditional mythologies. The Italians had just had a big success with a truly dreadful film starring muscleman Steve Reeves called Hercules (1957), and many Hercules films were to follow, each with at least one monster for the giant-thewed hero to subdue. Hercules was very successful in the USA, too.

O’Brien, who passed away in 1962, lived long enough to see some of his former pupil’s success, though most of the early films on which Harryhausen worked were comparatively minor: The seminal Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and Twenty Million Miles To Earth (1957). But in the late fifties Harryhausen, along with the producer with whom he nearly always worked, Charles Schneer, had a breakthrough film, The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad (1958). Very much an exotic fairy-tale largely aimed at children, but with a love interest as well, it turned out to appeal to children of all ages. The time was obviously ripe for this sort of romantic fabled based loosely on traditional mythologies. The Italians had just had a big success with a truly dreadful film starring muscleman Steve Reeves called Hercules (1957), and many Hercules films were to follow, each with at least one monster for the giant-thewed hero to subdue. Hercules was very successful in the USA, too.

The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad is amusing, but from the beginning the trouble with Harryhausen’s fantasy films, no matter who directed them (this time it was Nathan Juran), has always been the weak, highly episodic scripts. These seem to be dashed off rather mechanically to link together already-planned sequences featuring people versus monsters. In this case the animated creatures include a cyclops (a one-eyed giant with satyr-like legs), a dragon, a roc (a monstrous two-headed bird), a four-armed snake-woman and, finally, a sword-fighting skeleton modeled for Mr. Harryhausen by yours truly. The animated sequences are great fun, and often very well executed, but somehow his films seldom achieve the truly magical. The screenplays are blunderingly literal-minded, and the actors (especially Kerwin Matthews as Sinbad) come from a long way down in the hierarchy and were presumably hired cheap. Films of this kind are adroit, but rather crude, too. It may be paradoxical to suggest it, but although they have devoted much of their lives to the craft, Harryhausen and Schneer seem to have no more than a novice’s appreciation of what elements constitute true fantasy. For one thing, The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad never suggests anything by implication, by creating subtleties in atmosphere. The whole point animated fantasies of this sort is typically show the fantastic straight-on, in good light and, in this case, colour.

The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad is amusing, but from the beginning the trouble with Harryhausen’s fantasy films, no matter who directed them (this time it was Nathan Juran), has always been the weak, highly episodic scripts. These seem to be dashed off rather mechanically to link together already-planned sequences featuring people versus monsters. In this case the animated creatures include a cyclops (a one-eyed giant with satyr-like legs), a dragon, a roc (a monstrous two-headed bird), a four-armed snake-woman and, finally, a sword-fighting skeleton modeled for Mr. Harryhausen by yours truly. The animated sequences are great fun, and often very well executed, but somehow his films seldom achieve the truly magical. The screenplays are blunderingly literal-minded, and the actors (especially Kerwin Matthews as Sinbad) come from a long way down in the hierarchy and were presumably hired cheap. Films of this kind are adroit, but rather crude, too. It may be paradoxical to suggest it, but although they have devoted much of their lives to the craft, Harryhausen and Schneer seem to have no more than a novice’s appreciation of what elements constitute true fantasy. For one thing, The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad never suggests anything by implication, by creating subtleties in atmosphere. The whole point animated fantasies of this sort is typically show the fantastic straight-on, in good light and, in this case, colour.

There are great difficulties in combining animation with live action. One feels for poor Kerwin Matthews, who had to learn a sword-fight stroke-perfect, and use it against empty air (my miniature double was added later), while looking as if something was there. By this time, Harryhausen had named his animation process Dynamation, its unusual feature was that in the optical combination of live action and animation, he would sometimes have live action in the background, then the animated model in the mid-ground, and more live action in the foreground. Even sophisticated audiences used to animated figures against a real background were impressed by this sandwiching effect, which certainly heightened the illusion. On the other hand, the models in The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad have a slightly mechanical feel to them, as they almost always do in this kind of film. This is partly because every individual frame of animation is entirely still, whereas in ordinary films individual frames are very often blurred. When a succession of individually motionless frames is played back, a stroboscopic effect can be produced. This is to do with the way in which the brain perceives images and runs them together to produce the illusion of motion. No matter how smoothly the animation is achieved, the end result can still be jerky because of strobing. Schneer and Harryhausen had taken a risk with The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad. The conventional wisdom of the time held that Arabian Nights fantasies like The Thief Of Bagdad were now old hat. The last success in the field had been Sinbad The Sailor (1947) with Douglas Fairbanks Junior, so it was a great relief when the film did extremely well. A factor that certainly helped was the energetic musical score by Bernard Herrmann, one of his best.

There are great difficulties in combining animation with live action. One feels for poor Kerwin Matthews, who had to learn a sword-fight stroke-perfect, and use it against empty air (my miniature double was added later), while looking as if something was there. By this time, Harryhausen had named his animation process Dynamation, its unusual feature was that in the optical combination of live action and animation, he would sometimes have live action in the background, then the animated model in the mid-ground, and more live action in the foreground. Even sophisticated audiences used to animated figures against a real background were impressed by this sandwiching effect, which certainly heightened the illusion. On the other hand, the models in The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad have a slightly mechanical feel to them, as they almost always do in this kind of film. This is partly because every individual frame of animation is entirely still, whereas in ordinary films individual frames are very often blurred. When a succession of individually motionless frames is played back, a stroboscopic effect can be produced. This is to do with the way in which the brain perceives images and runs them together to produce the illusion of motion. No matter how smoothly the animation is achieved, the end result can still be jerky because of strobing. Schneer and Harryhausen had taken a risk with The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad. The conventional wisdom of the time held that Arabian Nights fantasies like The Thief Of Bagdad were now old hat. The last success in the field had been Sinbad The Sailor (1947) with Douglas Fairbanks Junior, so it was a great relief when the film did extremely well. A factor that certainly helped was the energetic musical score by Bernard Herrmann, one of his best.

Harryhausen worked steadily on a variety of fantasy projects with Schneer over the following few years, including The Three Worlds Of Gulliver (1959) and Mysterious Island (1961). His next major mythological project, however, was Jason And The Argonauts (1963). It is probably his best film. Unfortunately, it did not do as well at the box-office as its predecessor, so the sequel that seems to be promised by the ending was never made. Don Chaffey‘s direction is professional, and the animation is Harryhausen at his most meticulous. Indeed, even the screenplay has its moments, especially the amusingly acid dialogue of Zeus, as he watches the earthlings blundering around, from his perch in Olympus.

Harryhausen worked steadily on a variety of fantasy projects with Schneer over the following few years, including The Three Worlds Of Gulliver (1959) and Mysterious Island (1961). His next major mythological project, however, was Jason And The Argonauts (1963). It is probably his best film. Unfortunately, it did not do as well at the box-office as its predecessor, so the sequel that seems to be promised by the ending was never made. Don Chaffey‘s direction is professional, and the animation is Harryhausen at his most meticulous. Indeed, even the screenplay has its moments, especially the amusingly acid dialogue of Zeus, as he watches the earthlings blundering around, from his perch in Olympus.

The story (which had already been used as the basis of the Italian Hercules film a few years earlier) involves Jason collecting a crew of heroes together and setting sail to steal the Golden Fleece from Colchis, to use it as a rallying point for the people in his efforts to dispose of a tyrannical king. Nigel Green makes a very jolly Hercules, but Nancy Kovack is a listless Medea, and Jason (Todd Armstrong) is deplorably lacking in charisma. Nevertheless, this is a film in which Harryhausen comes closest in capturing the elusive magic that he has so often missed, both before and since. There are moments, like the vast creaking brass statue of Talos coming to life, or the screeching harpies persecuting the blind seer, when the film evokes a primal innocent world in which the natural and the supernatural co-exist, where behind the next hill horrors, miracles or even gods might lurk.

The story (which had already been used as the basis of the Italian Hercules film a few years earlier) involves Jason collecting a crew of heroes together and setting sail to steal the Golden Fleece from Colchis, to use it as a rallying point for the people in his efforts to dispose of a tyrannical king. Nigel Green makes a very jolly Hercules, but Nancy Kovack is a listless Medea, and Jason (Todd Armstrong) is deplorably lacking in charisma. Nevertheless, this is a film in which Harryhausen comes closest in capturing the elusive magic that he has so often missed, both before and since. There are moments, like the vast creaking brass statue of Talos coming to life, or the screeching harpies persecuting the blind seer, when the film evokes a primal innocent world in which the natural and the supernatural co-exist, where behind the next hill horrors, miracles or even gods might lurk.

Other effects sequences are a bit more knowing and modern, though well done: The fight with the seven-headed hydra, the rising of Poseidon from the waves to hold apart the clashing cliffs through which the ship must pass, and the ultimate fight with the skeletons grown from the hydra’s teeth. Children love the film, and for all one’s intellectual talk about the vulgarising of mythology and the crudity of the screenplay, there is no denying that Harryhausen contrived to bring a lot of sparkle, excitement and fun back into the world of fantastic cinema, which was beginning to lose sight of these qualities.

Other effects sequences are a bit more knowing and modern, though well done: The fight with the seven-headed hydra, the rising of Poseidon from the waves to hold apart the clashing cliffs through which the ship must pass, and the ultimate fight with the skeletons grown from the hydra’s teeth. Children love the film, and for all one’s intellectual talk about the vulgarising of mythology and the crudity of the screenplay, there is no denying that Harryhausen contrived to bring a lot of sparkle, excitement and fun back into the world of fantastic cinema, which was beginning to lose sight of these qualities.

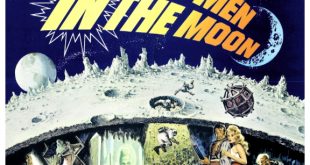

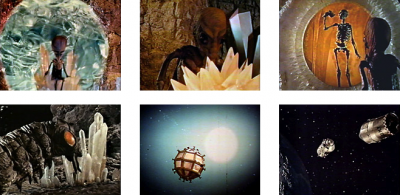

Films about space travel were not in fashion during the early sixties, but one notable exception was First Men In The Moon (1964) which, typically, hasn’t much to commend it apart from Harryhausen’s impressive special effects. Despite being based on a H.G. Wells novel and a screenplay partly written by Nigel Kneale, creator of the Quatermass series, it was played strictly for laughs and obviously aimed at the juvenile market. Lionel Jeffries camps it up as Professor Cavor, the inventor who creates an anti-gravity material that enables him to fly to the moon in a spherical spaceship. With him go Arnold Bedford (Edward Judd) and his fiancee Kate (Martha Hyer), and once on the moon they encounter the insect-like Selenites who prove none too friendly. Arnold and Kate finally escape back to Earth in the anti-gravity sphere but Professor Cavor stays behind to see if he can establish friendly relations with the lunar inhabitants. The film’s main twist was a contemporary prologue and epilogue: In the prologue we see a United Nations spaceship land on the moon and when the astronauts emerge they are amazed to find a British flag waiting for them. Back on Earth, a very old man in a rest home tells reporters that he put the Union Jack on the moon in 1899. He is, of course, Bedford, and as he tells his story, the film proper begins in flashback.

Films about space travel were not in fashion during the early sixties, but one notable exception was First Men In The Moon (1964) which, typically, hasn’t much to commend it apart from Harryhausen’s impressive special effects. Despite being based on a H.G. Wells novel and a screenplay partly written by Nigel Kneale, creator of the Quatermass series, it was played strictly for laughs and obviously aimed at the juvenile market. Lionel Jeffries camps it up as Professor Cavor, the inventor who creates an anti-gravity material that enables him to fly to the moon in a spherical spaceship. With him go Arnold Bedford (Edward Judd) and his fiancee Kate (Martha Hyer), and once on the moon they encounter the insect-like Selenites who prove none too friendly. Arnold and Kate finally escape back to Earth in the anti-gravity sphere but Professor Cavor stays behind to see if he can establish friendly relations with the lunar inhabitants. The film’s main twist was a contemporary prologue and epilogue: In the prologue we see a United Nations spaceship land on the moon and when the astronauts emerge they are amazed to find a British flag waiting for them. Back on Earth, a very old man in a rest home tells reporters that he put the Union Jack on the moon in 1899. He is, of course, Bedford, and as he tells his story, the film proper begins in flashback.

“The Wells novel had always been a favourite of mine,” said Harryhausen in his Film Fantasy Scrapbook. “I wanted to make a film of it for many years but every time I mention it to Charles Schneer he would always bring up the argument, and rightly so, that there was not enough variety in it as it stood for a feature production. Also, space science had advanced to such a degree that it would be difficult to make it believable for today’s audience. One day, while Charles was talking to writer Nigel Kneale, who is also a H.G. Wells enthusiast, Nigel came up with the brilliant idea that stimulated Charles into new interest in the project. Anyone who has seen it will agree that the prologue makes the whole thing work in a believable fashion.” Though it may be a clever touch, it doesn’t really enhance the original. There was more to the Wells novel than a story about two men flying to the moon and having trouble with the natives. Wells also used it as a means of exploring certain sociological concepts, but the Selenite’s Brave New World-style society is ignored by the filmmakers. The epilogue has the United Nations explorers finding the underground Selenite city empty and in a state of decay. Bedford remembers that Cavor had a cold on the moon and deduces that his germs must have wiped out the Selenite civilisation. This black joke – a reversal of the ending of The War Of The Worlds – must surely have been another Nigel Kneale contribution.

“The Wells novel had always been a favourite of mine,” said Harryhausen in his Film Fantasy Scrapbook. “I wanted to make a film of it for many years but every time I mention it to Charles Schneer he would always bring up the argument, and rightly so, that there was not enough variety in it as it stood for a feature production. Also, space science had advanced to such a degree that it would be difficult to make it believable for today’s audience. One day, while Charles was talking to writer Nigel Kneale, who is also a H.G. Wells enthusiast, Nigel came up with the brilliant idea that stimulated Charles into new interest in the project. Anyone who has seen it will agree that the prologue makes the whole thing work in a believable fashion.” Though it may be a clever touch, it doesn’t really enhance the original. There was more to the Wells novel than a story about two men flying to the moon and having trouble with the natives. Wells also used it as a means of exploring certain sociological concepts, but the Selenite’s Brave New World-style society is ignored by the filmmakers. The epilogue has the United Nations explorers finding the underground Selenite city empty and in a state of decay. Bedford remembers that Cavor had a cold on the moon and deduces that his germs must have wiped out the Selenite civilisation. This black joke – a reversal of the ending of The War Of The Worlds – must surely have been another Nigel Kneale contribution.

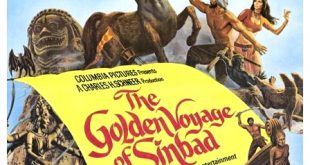

One way of making our ordinary world seem fantastic is to create an entirely fantastic world from the ground up. Until the eighties, when the popularity of so-called sword-and-sorcery novels became so great that filmmakers could not afford to ignore it, there were very few producers who were prepared to take on the Herculean task of building an entirely ‘other’ world of magic, with all the problem of sets and special effects that the work would entail. Existing myths were the obvious source of such movies, though later on, as filmmakers began to put greater trust in the audience’s capacity to lose themselves in a story, it became quite common to invent new fantastic worlds altogether, usually set in some unspecified archaic past, or in some unspecified alternate universe – Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977) did both. But earlier in the seventies, it was Ray Harryhausen who persevered with the business of building fantasy worlds while others steered clear. Even if one has reservations about the quality of the end product, one has to admire the way Harryhausen, despite major obstacles, has always stuck to his ‘fantasy’ guns. With co-producer Charles Schneer, he made three magic-and-monsters movies within ten years (doing the special effects himself, of course), the first of which was The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad (1973).

One way of making our ordinary world seem fantastic is to create an entirely fantastic world from the ground up. Until the eighties, when the popularity of so-called sword-and-sorcery novels became so great that filmmakers could not afford to ignore it, there were very few producers who were prepared to take on the Herculean task of building an entirely ‘other’ world of magic, with all the problem of sets and special effects that the work would entail. Existing myths were the obvious source of such movies, though later on, as filmmakers began to put greater trust in the audience’s capacity to lose themselves in a story, it became quite common to invent new fantastic worlds altogether, usually set in some unspecified archaic past, or in some unspecified alternate universe – Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977) did both. But earlier in the seventies, it was Ray Harryhausen who persevered with the business of building fantasy worlds while others steered clear. Even if one has reservations about the quality of the end product, one has to admire the way Harryhausen, despite major obstacles, has always stuck to his ‘fantasy’ guns. With co-producer Charles Schneer, he made three magic-and-monsters movies within ten years (doing the special effects himself, of course), the first of which was The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad (1973).

At last Harryhausen’s persistence was rewarded. After a series of semi-flops like One Million Years BC (1966) and The Valley Of Gwangi (1969), The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad turned out to be his most successful film at the box-office yet – it even did better than The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad. The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad, with a screenplay by prolific English writer Brian Clemens, and a score by Miklos Rozsa, succeeded in projecting an atmosphere of the uncanny more successfully than most of his other work, before or since. This time Sinbad was played by John Phillip Law (post-Barbarella), while Tom Baker (pre-Doctor Who) played the wicked magician Koura. Although the film’s title suggests a mythology from The Arabian Nights, this hodgepodge takes elements from Hindu (a statue of the six-armed goddess Kali comes to life) and Greek (a centaur battles a griffin) mythologies. Filmed in Spain, the story recounts an epic quest for the third part of an amulet of which the first part is held by Sinbad and the second by the Grand Vizier whose face, destroyed by Koura, is hidden behind a forbidding golden mask. Their quest takes them to Lemuria, but some of the better effects take place early in the piece: The evil little winged homunculus that eavesdrops on their plans, and the ship’s figurehead that slowly turns from the prow, tears itself out of the wooden frame, snatches a vital map, and swims away. There is a real sense of wonder here, though in other parts of the film the fantasy is much more mechanical, especially the centaur’s battle with the griffin).

At last Harryhausen’s persistence was rewarded. After a series of semi-flops like One Million Years BC (1966) and The Valley Of Gwangi (1969), The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad turned out to be his most successful film at the box-office yet – it even did better than The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad. The Golden Voyage Of Sinbad, with a screenplay by prolific English writer Brian Clemens, and a score by Miklos Rozsa, succeeded in projecting an atmosphere of the uncanny more successfully than most of his other work, before or since. This time Sinbad was played by John Phillip Law (post-Barbarella), while Tom Baker (pre-Doctor Who) played the wicked magician Koura. Although the film’s title suggests a mythology from The Arabian Nights, this hodgepodge takes elements from Hindu (a statue of the six-armed goddess Kali comes to life) and Greek (a centaur battles a griffin) mythologies. Filmed in Spain, the story recounts an epic quest for the third part of an amulet of which the first part is held by Sinbad and the second by the Grand Vizier whose face, destroyed by Koura, is hidden behind a forbidding golden mask. Their quest takes them to Lemuria, but some of the better effects take place early in the piece: The evil little winged homunculus that eavesdrops on their plans, and the ship’s figurehead that slowly turns from the prow, tears itself out of the wooden frame, snatches a vital map, and swims away. There is a real sense of wonder here, though in other parts of the film the fantasy is much more mechanical, especially the centaur’s battle with the griffin).

The sequel, Sinbad And The Eye Of The Tiger (1977), was rather disappointing. John Wayne’s son Patrick Wayne starred as Sinbad, without any of his old man’s charisma. The script is amazingly vapid, and the film has an old-fashioned look about it, and plods along at an unvarying pace, building very little tension. Thus Harryhausen’s effects appear in a frame that does not set them off to advantage, though there is plenty of entertainment in the giant walrus, the giant bee, the minotaur and the horned troglodyte. The most touching effects centre on the young man who is turned into a big baboon.

The sequel, Sinbad And The Eye Of The Tiger (1977), was rather disappointing. John Wayne’s son Patrick Wayne starred as Sinbad, without any of his old man’s charisma. The script is amazingly vapid, and the film has an old-fashioned look about it, and plods along at an unvarying pace, building very little tension. Thus Harryhausen’s effects appear in a frame that does not set them off to advantage, though there is plenty of entertainment in the giant walrus, the giant bee, the minotaur and the horned troglodyte. The most touching effects centre on the young man who is turned into a big baboon.

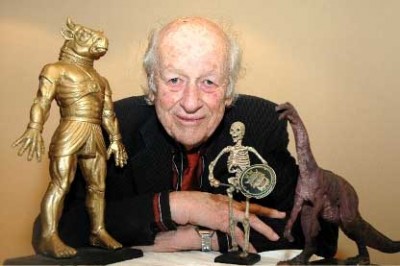

Clash Of The Titans (1981), which was backed by MGM, gave Harryhausen the largest budget he has ever had to work with. It is quite a lavish production, with appearances by big stars such as Laurence Olivier, Burgess Meredith and Maggie Smith, but there is something sad about it, as if Harryhausen has been trapped in some sort of time-loop ever since The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad (1958), the same awkwardly shambling monsters and trite plot looking more old-fashioned with each new film. The story (Perseus’s love for Andromeda and their many trials before her final rescue from the Kraken) is typically episodic – for Harryhausen, all stories run in straight lines – but his animation is as good as ever, the best things this time round being the winged horse Pegasus, the fight with the melancholy monster Calibos, the giant scorpions, the Kraken and, best of all, the fiendish gorgon Medusa with her hair of writhing snakes and her cave full of the stone bodies of previous victims, caught in postures of agony.

Clash Of The Titans (1981), which was backed by MGM, gave Harryhausen the largest budget he has ever had to work with. It is quite a lavish production, with appearances by big stars such as Laurence Olivier, Burgess Meredith and Maggie Smith, but there is something sad about it, as if Harryhausen has been trapped in some sort of time-loop ever since The Seventh Voyage Of Sinbad (1958), the same awkwardly shambling monsters and trite plot looking more old-fashioned with each new film. The story (Perseus’s love for Andromeda and their many trials before her final rescue from the Kraken) is typically episodic – for Harryhausen, all stories run in straight lines – but his animation is as good as ever, the best things this time round being the winged horse Pegasus, the fight with the melancholy monster Calibos, the giant scorpions, the Kraken and, best of all, the fiendish gorgon Medusa with her hair of writhing snakes and her cave full of the stone bodies of previous victims, caught in postures of agony.

But special effects in the modern world had been moving on, and the optical processing that unites animation with live action looked pretty weak alongside its contemporaries. It had blue fringing around the models, fuzzy background plates and a generally grainy appearance. The best performance in the film is that of the spirited and intelligent Judi Bowker as Andromeda, the worst may be that of the dopey mechanical owl Bubo, a creature of metal whose mannerisms seem to be inspired by R2-D2. Clash Of The Titans is good fun, but could have been so much better. Their final film together, it seemed the imaginations of Harryhausen and Schneer been petrified by the numbing waters of some mythic stagnant pond.

But special effects in the modern world had been moving on, and the optical processing that unites animation with live action looked pretty weak alongside its contemporaries. It had blue fringing around the models, fuzzy background plates and a generally grainy appearance. The best performance in the film is that of the spirited and intelligent Judi Bowker as Andromeda, the worst may be that of the dopey mechanical owl Bubo, a creature of metal whose mannerisms seem to be inspired by R2-D2. Clash Of The Titans is good fun, but could have been so much better. Their final film together, it seemed the imaginations of Harryhausen and Schneer been petrified by the numbing waters of some mythic stagnant pond.

Despite the relatively successful box-office returns for Clash of the Titans, more sophisticated technology (such as Go-Motion developed by Industrial Light And Magic) had begun to eclipse Harryhausen’s production techniques, so MGM passed on funding a sequel (to be called Force Of The Trojans) causing Harryhausen and Schneer to retire from active film-making. Harryhausen maintained his friendship with his long-time producer, who lived next door to him in a suburb of London until Schneer moved full-time to the USA (Charles Schneer passed away in 2009 aged 88). And it’s on that sad note I’ll bid you farewell and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to freeze the blood in your veins with more sickening horror to make your stomach turn and your flesh crawl in yet another fear-filled fang-fest for…Horror News! Toodles!

Despite the relatively successful box-office returns for Clash of the Titans, more sophisticated technology (such as Go-Motion developed by Industrial Light And Magic) had begun to eclipse Harryhausen’s production techniques, so MGM passed on funding a sequel (to be called Force Of The Trojans) causing Harryhausen and Schneer to retire from active film-making. Harryhausen maintained his friendship with his long-time producer, who lived next door to him in a suburb of London until Schneer moved full-time to the USA (Charles Schneer passed away in 2009 aged 88). And it’s on that sad note I’ll bid you farewell and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to freeze the blood in your veins with more sickening horror to make your stomach turn and your flesh crawl in yet another fear-filled fang-fest for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews