SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Scientist Zac Hobson wakes up in the morning and soon he finds that he seems to be alone in the world. He drives around unsuccessfully seeking out other survivors and tries to figure out what might have happened. After a few days, he shows traces of insanity due to the loneliness. Out of the blue, Zac finds Joanne and they stay together looking for survivors. Zac meets the distrustful black Api and Zac explains that he believes that the project that he was researching in the government laboratory might have caused the phenomenon. Now the trio decide to blow-up the laboratory to stop the experiment.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Although born in Leeds in Yorkshire, author-screenwriter Craig Harrison has since adopted New Zealand as his true home. Since he didn’t get many chances to write creatively at school, Harrison drifted into science subjects and, by the age of sixteen, was giving lectures to the British Interplanetary Society. Awards include the Elmwood Jubilee prize, the JC Reid award and the New Zealand Theatre Federation prize. His output has ranged widely, from science fiction and fantasy to parody, and has written several novels, short stories, plays, satirical works and television comedies. When he moved to New Zealand in 1966, he arrived at the centre of Auckland on a Sunday morning and found it completely deserted, making him feel like the proverbial last man on Earth. Unbeknownst to Harrison, most New Zealanders back then would often take the entire weekend off and sleep-in late, and the experience inspired his 1981 novel The Quiet Earth, which eventually led to the release of the film based on the book of the same name.

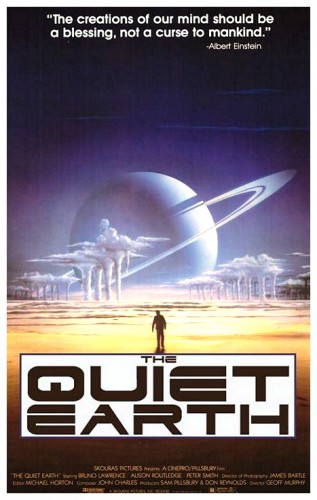

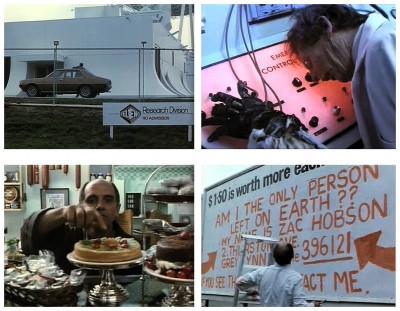

Apocalyptic science fiction doesn’t need the overblown hyperbole of an Armageddon (1997) or a Deep Impact (1997). The Quiet Earth (1985) is an end-of-the-world thriller featuring few big-budget special effects and no reliance at all on the now ubiquitous over-use of computer graphics to convey its sense of the end. Made for only one million dollars in mid-eighties money, The Quiet Earth is a textbook example of how to make an effective science fiction movie without a Hollywood-sized budget. Zac Hobson (Bruno Lawrence) wakes up at 6.12am to discover he is the last man on earth. Something has happened, referred to as ‘the effect’ – everyone in Auckland seems to have vanished, leaving no trace of their departure – no bodies, no residue, nothing. Meals are left half-eaten on dinner tables, planes have fallen out of the sky, kettles left boiling over. The phones still work, but there is no-one around to answer them.

Apocalyptic science fiction doesn’t need the overblown hyperbole of an Armageddon (1997) or a Deep Impact (1997). The Quiet Earth (1985) is an end-of-the-world thriller featuring few big-budget special effects and no reliance at all on the now ubiquitous over-use of computer graphics to convey its sense of the end. Made for only one million dollars in mid-eighties money, The Quiet Earth is a textbook example of how to make an effective science fiction movie without a Hollywood-sized budget. Zac Hobson (Bruno Lawrence) wakes up at 6.12am to discover he is the last man on earth. Something has happened, referred to as ‘the effect’ – everyone in Auckland seems to have vanished, leaving no trace of their departure – no bodies, no residue, nothing. Meals are left half-eaten on dinner tables, planes have fallen out of the sky, kettles left boiling over. The phones still work, but there is no-one around to answer them.

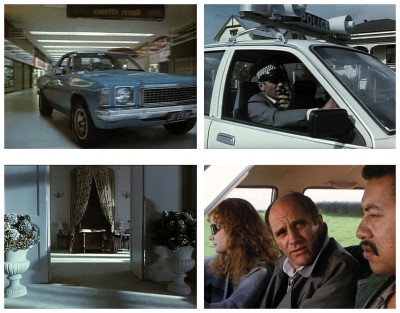

Zac goes to the laboratory where he has been working on something called Project Flashlight – an international project funded by the USA to create a defensive shield around the entire planet – which may be responsible for ‘the effect’ (not to be confused with Operation Flashlight, a real-life US military experiment involving miniature atomic blasts the size of a small room). At first, Zac enjoys being the only person on the planet, living it up with whatever he can find, but gradually that decadence and loneliness starts moving towards madness. Just in time comes Joanne (Alison Routledge) and Api (Peter Smith), demonstrating that not everyone had vanished in ‘the effect’. The three also have something else in common – all three died at the same moment of the cataclysm, and their deaths at that moment seems to have saved them: Zac overdosed on sleeping pills after realising what Project Flashlight entailed; Api was engaged in a fight with his former friend over a woman; Joanne was electrocuted by a faulty hairdryer.

Zac goes to the laboratory where he has been working on something called Project Flashlight – an international project funded by the USA to create a defensive shield around the entire planet – which may be responsible for ‘the effect’ (not to be confused with Operation Flashlight, a real-life US military experiment involving miniature atomic blasts the size of a small room). At first, Zac enjoys being the only person on the planet, living it up with whatever he can find, but gradually that decadence and loneliness starts moving towards madness. Just in time comes Joanne (Alison Routledge) and Api (Peter Smith), demonstrating that not everyone had vanished in ‘the effect’. The three also have something else in common – all three died at the same moment of the cataclysm, and their deaths at that moment seems to have saved them: Zac overdosed on sleeping pills after realising what Project Flashlight entailed; Api was engaged in a fight with his former friend over a woman; Joanne was electrocuted by a faulty hairdryer.

Gradually the three find others who had survived ‘the effect’ but could not handle the loneliness and ended their new lives. A love triangle develops, but Zac is more concerned about his observations – several universal physical constants are changing, causing the sun’s output to fluctuate. Zac fears that ‘the effect’ will occur again and decides to destroy the laboratory in an attempt to stop it. The three put aside their personal differences and decide to drive a truckload of explosives into the installation, only to be stopped at the perimeter by dangerous levels of ionising radiation emanating from the lab. Zac tells Joanne and Api that he’s going into town to retrieve a remote control device that will allow him to send the truck into the facility. Later, Joanne and Api hear the truck and realise that Zac hasn’t gone into town at all, as he drives the truck onto the weakened roof of the laboratory, which collapses, and Zac triggers the explosives.

Gradually the three find others who had survived ‘the effect’ but could not handle the loneliness and ended their new lives. A love triangle develops, but Zac is more concerned about his observations – several universal physical constants are changing, causing the sun’s output to fluctuate. Zac fears that ‘the effect’ will occur again and decides to destroy the laboratory in an attempt to stop it. The three put aside their personal differences and decide to drive a truckload of explosives into the installation, only to be stopped at the perimeter by dangerous levels of ionising radiation emanating from the lab. Zac tells Joanne and Api that he’s going into town to retrieve a remote control device that will allow him to send the truck into the facility. Later, Joanne and Api hear the truck and realise that Zac hasn’t gone into town at all, as he drives the truck onto the weakened roof of the laboratory, which collapses, and Zac triggers the explosives.

Zac wakes up to find himself lying face down on a beach. There are strange cloud formations resembling waterspouts rising out of the ocean and, as he walks to the water’s edge, an enormous ringed planet slowly appears over the horizon. Zac stares in disbelief, then realises he is still holding his tape recorder. He lifts it up as if to speak, then lowers it, completely bewildered. The precise meaning of this final scene is left up to the audience, but according to the DVD commentary by producer-screenwriter Sam Pillsbury: “We all thought it was quite simple, I mean, our intention was just that. What happened was, he died at the moment of the effect for a second time and he’s now found himself in another world! What the hell’s he gonna do? It may well have been something to do with purgatory and, you know, you being trapped in cyclical and going back into having to relive your thing until you work out your karma, not to mix metaphors. Anyway, enigmatic is good I think, to a certain extent.”

Zac wakes up to find himself lying face down on a beach. There are strange cloud formations resembling waterspouts rising out of the ocean and, as he walks to the water’s edge, an enormous ringed planet slowly appears over the horizon. Zac stares in disbelief, then realises he is still holding his tape recorder. He lifts it up as if to speak, then lowers it, completely bewildered. The precise meaning of this final scene is left up to the audience, but according to the DVD commentary by producer-screenwriter Sam Pillsbury: “We all thought it was quite simple, I mean, our intention was just that. What happened was, he died at the moment of the effect for a second time and he’s now found himself in another world! What the hell’s he gonna do? It may well have been something to do with purgatory and, you know, you being trapped in cyclical and going back into having to relive your thing until you work out your karma, not to mix metaphors. Anyway, enigmatic is good I think, to a certain extent.”

The Quiet Earth won a huge number of industry awards in New Zealand including Best Film, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Director (Geoff Murphy), Best Actor (Bruno Lawrence), Best Supporting Actor (Peter Smith), Best Editor (Michael J. Horton), Best Cinematographer (James Bartle) and Best Production Design (Josephine Ford). The first half of the film is certainly chilling as Zac roams around the empty city, surrounded by the debris left behind by the capitalist West but, unfortunately, the more plot-oriented activities that dominate the second half of the film (after Joanne and Api enter the scene) lessen the movie’s overall power. Although populated by fleshed-out characters and powerful performances, the subject matter is hardly groundbreaking. Richard Matheson‘s novel I Am Legend is perhaps the most famous example the last-man-on-earth story, being filmed at least three times as The Last Man On Earth (1964) starring Vincent Price, The Omega Man (1971) starring Charlton Heston, and I Am Legend (2007) starring Will Smith.

The Quiet Earth won a huge number of industry awards in New Zealand including Best Film, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Director (Geoff Murphy), Best Actor (Bruno Lawrence), Best Supporting Actor (Peter Smith), Best Editor (Michael J. Horton), Best Cinematographer (James Bartle) and Best Production Design (Josephine Ford). The first half of the film is certainly chilling as Zac roams around the empty city, surrounded by the debris left behind by the capitalist West but, unfortunately, the more plot-oriented activities that dominate the second half of the film (after Joanne and Api enter the scene) lessen the movie’s overall power. Although populated by fleshed-out characters and powerful performances, the subject matter is hardly groundbreaking. Richard Matheson‘s novel I Am Legend is perhaps the most famous example the last-man-on-earth story, being filmed at least three times as The Last Man On Earth (1964) starring Vincent Price, The Omega Man (1971) starring Charlton Heston, and I Am Legend (2007) starring Will Smith.

But the film that The Quiet Earth most resembles is The World The Flesh And The Devil (1958), an MGM film written and directed by Ranald MacDougall and based very loosely on the Matthew Phipp Shiel novel The Purple Cloud. Similar to Arch Oboler‘s production Five (1951), The World The Flesh And The Devil reduces the number of survivors in a nuclear-bomb-ravaged America to three – a young woman (inger Stevens), a charming black man (Harry Belafonte) and a cynical world-weary adventurer (Mel Ferrer). Compared to Oboler’s talkative dreary film, MacDougall’s post-atomic war vision is superior in both script and direction. The plot is simple: Black man finds white girl, white male racist finds both and trouble ensues. However, unlike The Quiet Earth, the film ends with all three of them walking off into the sunset together hand-in-hand, the first post-nuclear ménage à trois, but that’s another story for another time. Please join me next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the Public Domain for…Horror News! Toodles!

But the film that The Quiet Earth most resembles is The World The Flesh And The Devil (1958), an MGM film written and directed by Ranald MacDougall and based very loosely on the Matthew Phipp Shiel novel The Purple Cloud. Similar to Arch Oboler‘s production Five (1951), The World The Flesh And The Devil reduces the number of survivors in a nuclear-bomb-ravaged America to three – a young woman (inger Stevens), a charming black man (Harry Belafonte) and a cynical world-weary adventurer (Mel Ferrer). Compared to Oboler’s talkative dreary film, MacDougall’s post-atomic war vision is superior in both script and direction. The plot is simple: Black man finds white girl, white male racist finds both and trouble ensues. However, unlike The Quiet Earth, the film ends with all three of them walking off into the sunset together hand-in-hand, the first post-nuclear ménage à trois, but that’s another story for another time. Please join me next week when I have the opportunity to throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the Public Domain for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews