SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Police detective John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson is asked by an old college friend, Gavin Elster, if he would have a look into his wife Madeleine’s odd behavior. Lately, she’s taken to believing that she is the reincarnation of a woman who died many years ago and Elster is concerned about her sanity. Scottie follows her and rescues her from an apparent suicide attempt when she jumps into San Francisco bay. He gets to know her and falls in love with her. They go to an old mission church and he is unable to stop her from climbing to the top of the steeple, owing to his vertigo, where she jumps to her death. A subsequent inquiry finds that she committed suicide but faults Scottie for not stopping her in the first place. Several months later he meets Judy Barton, a woman who is the spitting image of Madeleine. He can’t explain it, but she is identical to the woman who died. He tries to re-make her into Madeleine’s image by getting her to dye her hair and wear the same type of clothes. He soon begins to realize however that he has been duped and was a pawn in a complex piece of theater that was meant to end in tragedy.”

REVIEW:

Alfred Hitchcock began his film career in 1920 as a graphic artist of silent film title cards, soon becoming designer, scriptwriter and director. After nine silent films including The Lodger (1927) and The Ring (1927) he directed the first British sound film, Blackmail (1929), followed by a number of superb thrillers: The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The Thirty-Nine Steps (1934), Young Innocent (1937) and The Lady Vanishes (1938). He was then invited to America by producer David O. Selznick to make Rebecca (1940) and remained in the USA for most of his life. Hitchcock became the complete filmmaker, an auteur to whom no aspect of the filmic structure is a mystery. Every image that appears on screen has been calculated precisely, from the screenplay and photographic composition to the editing and soundtrack. Even the marketing of the finished product was a major part of Hitchcock’s concern, and the gleam in his eye is that of a born showman. His name is known to almost every person who has ever entered a cinema and his personality is more familiar to us than those of his many major stars.

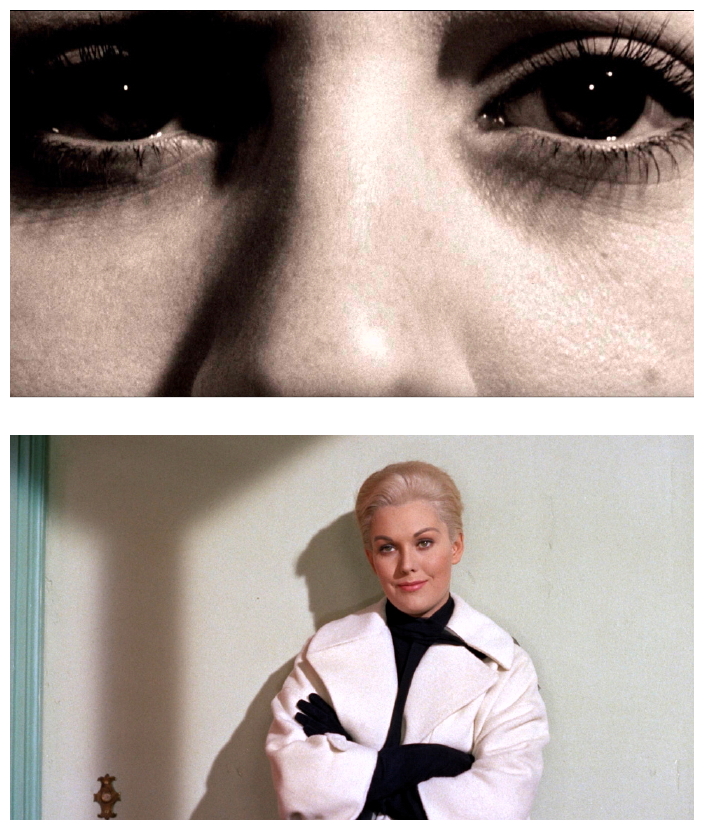

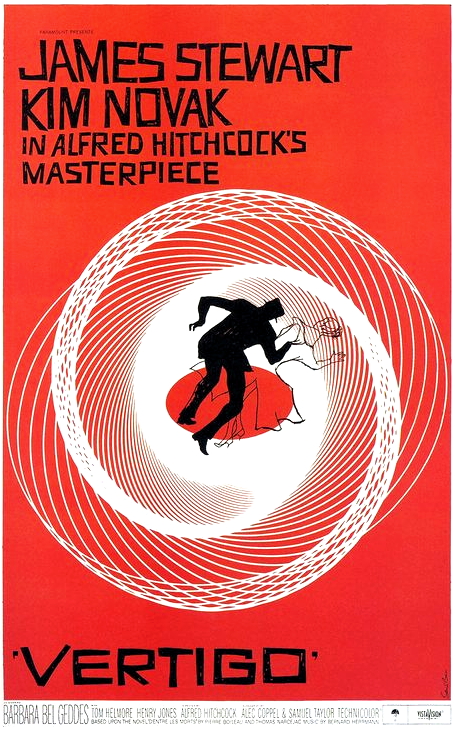

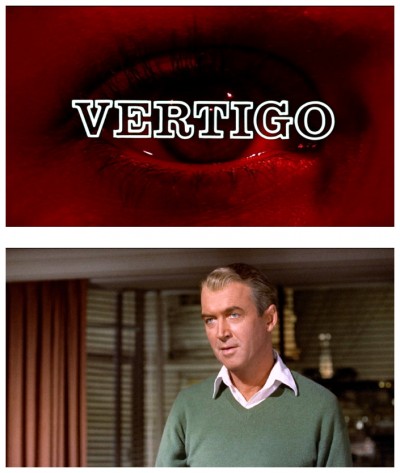

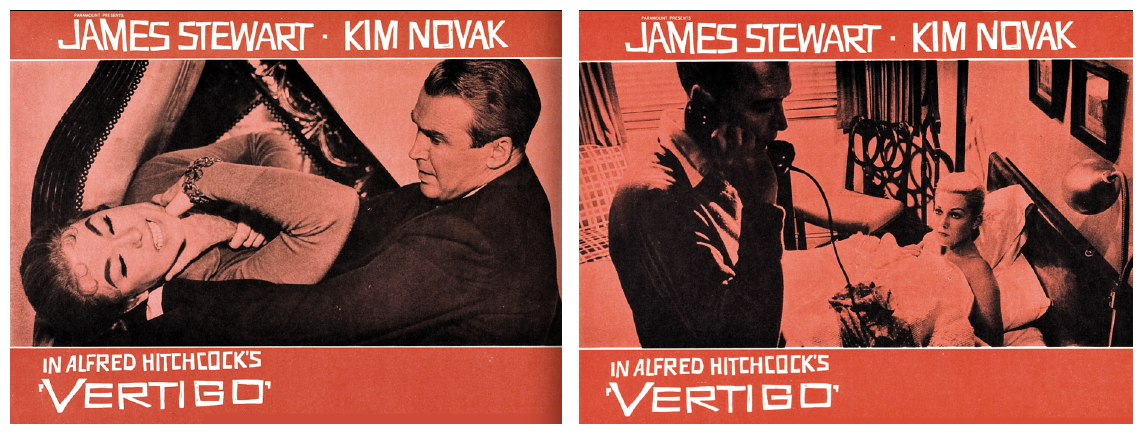

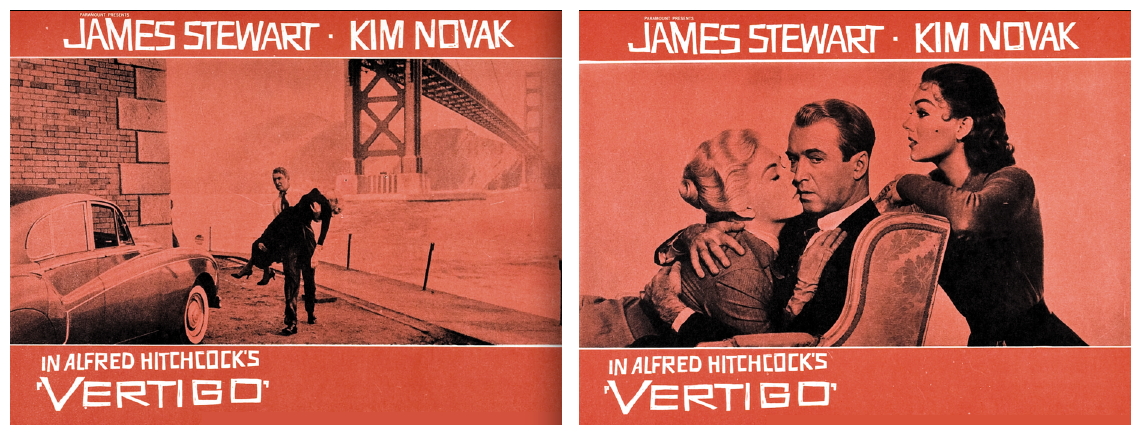

Vertigo (1958) proved to be one of Hitchcock’s most intriguing films. It was based on a novel by two French writers, Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, who had been responsible for the original story on which Henri-Georges Clouzot‘s film Les Diaboliques (1955) had been based. Although the book had been published before Hitchcock purchased it as a filmable property, the two authors had specifically constructed the plot along Hitchcockian lines in the hope that he would be tempted. Their ploy did indeed work. The film begins with a chase across a San Francisco roof, in which police detective John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson (James Stewart) slips and finds himself dangling from a drainpipe high above the street. A police officer who tries to save him plummets to his death, and suddenly Scottie develops a fear of heights, experiencing extreme vertigo whenever he looks down.

Vertigo (1958) proved to be one of Hitchcock’s most intriguing films. It was based on a novel by two French writers, Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, who had been responsible for the original story on which Henri-Georges Clouzot‘s film Les Diaboliques (1955) had been based. Although the book had been published before Hitchcock purchased it as a filmable property, the two authors had specifically constructed the plot along Hitchcockian lines in the hope that he would be tempted. Their ploy did indeed work. The film begins with a chase across a San Francisco roof, in which police detective John ‘Scottie’ Ferguson (James Stewart) slips and finds himself dangling from a drainpipe high above the street. A police officer who tries to save him plummets to his death, and suddenly Scottie develops a fear of heights, experiencing extreme vertigo whenever he looks down.

In the next scene we see the retired Scottie is safe, but it’s significant to note that Hitchcock never shows him being rescued, in fact he makes it seem as if rescue is impossible. By leaving Scottie hanging in mid-air, Hitchcock instills in us the feeling (which lasts the entire film) that Scottie has slipped into a surreal dreamlike netherworld that exists between life and death, present and past, real and illusionary. Having left the force and set up a private agency, he is asked by an old college friend named Elster (Tom Helmore) to shadow his wife, a potential suicide case. Feeling guilty because a cop died in his place, Scottie becomes strangely attracted to death, which is embodied by his quarry, the beautiful ethereal Madeleine (Kim Novak). Scottie jumps headlong into the deathly world through which this unhappy woman sleepwalks.

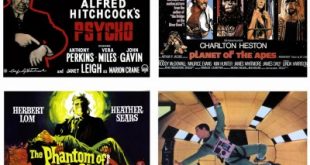

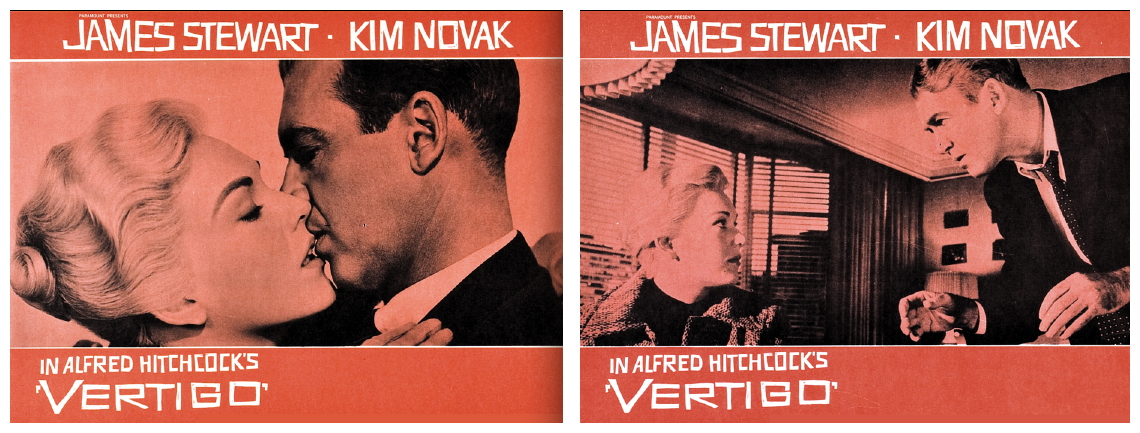

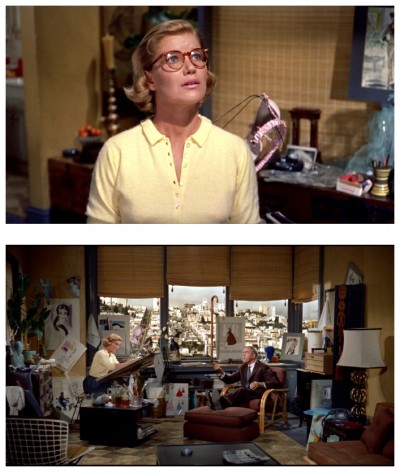

They finally meet when he saves her from the ocean during a suicide bid. He falls in love with Madeleine but, owing to his vertigo, is later unable to stop her from throwing herself off the tower of an old mission (conveniently, Scottie never looks back at the body). Mourning for Madeleine, he suffers acute nervous depression and is nursed back to health by his fiancee Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes). Six months later on the streets of San Francisco, he spots a girl named Judy Barton (Kim Novak) who has a marked physical resemblance to his former love and is convinced – despite her denials that she is the same girl – and he falls in love again. He persuades her to dye her red hair blonde like Madeleine and, when the exact image is recreated, he is finally able to unravel the extraordinary truth – that there was a deliberate hoax to cloak a murder.

They finally meet when he saves her from the ocean during a suicide bid. He falls in love with Madeleine but, owing to his vertigo, is later unable to stop her from throwing herself off the tower of an old mission (conveniently, Scottie never looks back at the body). Mourning for Madeleine, he suffers acute nervous depression and is nursed back to health by his fiancee Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes). Six months later on the streets of San Francisco, he spots a girl named Judy Barton (Kim Novak) who has a marked physical resemblance to his former love and is convinced – despite her denials that she is the same girl – and he falls in love again. He persuades her to dye her red hair blonde like Madeleine and, when the exact image is recreated, he is finally able to unravel the extraordinary truth – that there was a deliberate hoax to cloak a murder.

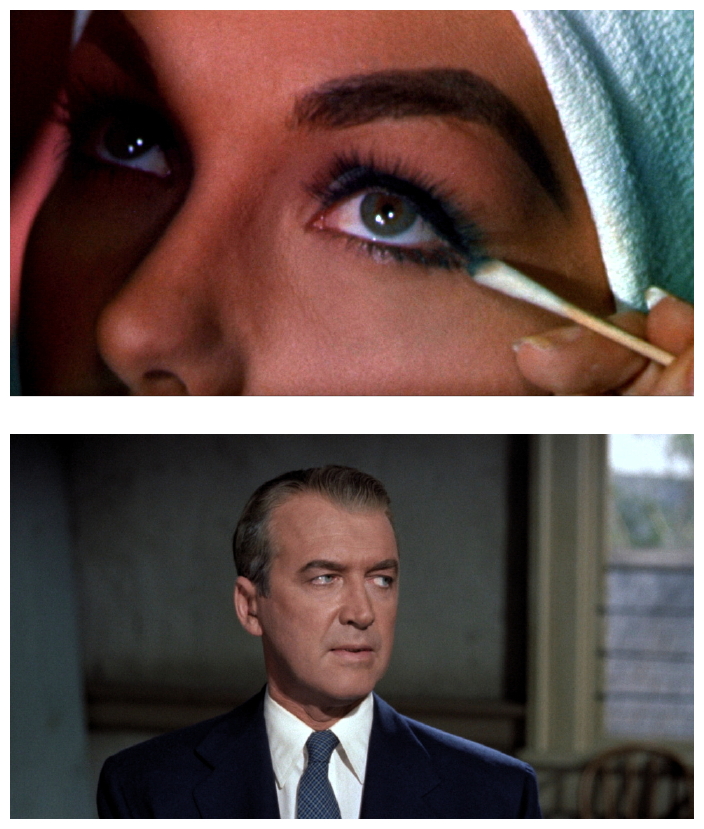

What attracted Hitchcock to the project is that Scottie essentially wants to indulge in necrophilia by resurrecting a dead woman and making love to her. He’s also showing, through Scottie, how many directors can turn a simple girl like Kim Novak into a haunting screen presence. Novak’s style of acting is excellently in-tune with the enigma of the story although, at the time of filming, Hitchcock had serious reservations about her taking the part which had been designed specifically for Vera Miles, who was no longer available. Novak had been given a very typical Hollywood buildup during the mid-fifties in an attempt to promote her as a latter-day love goddess. That the attempt failed was not so much due to her inadequacies as an actress, as to atrocious miscasting and insensitivity towards her subtle-but-undoubted talent. In fact, Hitchcock was able to extract from her one of her most satisfying performances ever.

Hitchcock sets up distinctions between elegant Madeleine and Judy, and between Madeleine and Midge, the pert down-to-earth fiancee whom Scottie dumps for Madeleine. Hitchcock told me that, given a choice of women, men are so weak they’ll always pick the helpless over the independent, the attractive over the plain, the frigid over the accessible, and the illusionary and the real. For two thirds of the film we believe we’re watching a mystery in which Scottie will uncover Elster’s murder plot and that Scottie was the patsy all along. But suddenly the audience is let in on Judy being Madeleine, and the movie becomes an intense psychological character study of Scottie. It’s regarded by many as a structural weakness of the film that Hitchcock reveals the secret to the audience only two-thirds of the way through, but left Scottie guessing.

It’s certainly true that his main interest in the story – a neurotic detective recreating the image of a girl from his past – would have preserved its mystery more effectively if the murder plot had not been shown. It is as though we, the audience, have been led up a parapsychological gum-tree. The structure is unique and brilliant, yes, but it may become infuriating for some. I think I’d rather watch Scottie unravel a mystery, than to watch Scottie become unraveled himself, becoming unbearably obsessive, tyrannical and self-destructive. We start cheering for the fragile Judy (despite what she did to him) and start despising Scottie, which is why the tragic ending is so unsatisfying and downright depressing. That being said, the visuals in Vertigo are superb: Robert Burk‘s eerie camerawork makes certain scenes feel like the past and the present are mingled together, and the topography of San Francisco is deployed to its full advantage with a slow dignified car chase, the vehicles of Novak and Stewart glide quietly and gently down the same hilly streets that, a decade later, would reverberate with the squeals of Steve McQueen‘s tyres in Bullitt (1968).

The mission scenes are enlivened by two remarkable shots: a vertical one down the staircase using a forward zoom on a reversing camera to convey the effect of Stewart’s sense of vertigo; and an overhead exterior shot showing him walking away from the church with the girl’s body sprawled on the roof where she has fallen. It was the first Hitchcock film with credit titles designed by noted graphic artist Saul Bass, who would join Team Hitchcock along with cameraman Robert Burk, composer Bernard Herrmann, and editor George Tomasini. There is a studied care and precision in Hitchcock’s craft which have invariably given his films a distinctive polish. His pre-production capacity is legendary: Before a single frame of film is exposed, he would read the script repeatedly, rejecting and rewriting, he would never improvise on-set, his actors rehearsed their roles to perfection, his cinematographer knew exactly what was required, he had no need to look through the viewfinder. When asked about his filmmaking methods, he would simply state, “My films are made on paper.” With that thought in mind I’ll thank you for reading, and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to simultaneously raise both hackles and cackles with more dreadful dross from the drains of Los Angeles in another trouser-moistening fear-filled film review for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews