SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“Jack The Ripper is on the loose killing prostitutes in London’s Whitechapel district and Sherlock Holmes, assisted by his friend Doctor Watson, is on the case. From the pathologist’s findings. Holmes concludes that the man had some medical training, most likely as a surgeon. Various clues lead him to the son of an aristocrat who was studying medicine but has since vanished since marrying a prostitute. His investigation leads him to a local street mission for the poor where Doctor Murray, an avowed socialist who works part-time as a police surgeon, does his best to provide the basic necessities of life to London’s poor and destitute. Holmes soon has a short list of possible suspects including Doctor Murray, his assistant Sally Young and Max Steiner, a pub owner and pimp. The inevitable final confrontation reveals the identity of the killer.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

The sixties brought a wind of change in the cinema and permissiveness raised its head. From the almost naive self-conscious flashes of bosom and veiled references to sex in the early sixties, we moved to flaunted full-frontals and explicit sexual simulation in the late sixties and to this day. In this climate of change and greater sexual freedom in the cinema, the character of the Hero also inevitably changed. In the forefront of this attack was James Bond, Ian Fleming‘s sexual athlete, who was first brought to the screen in Doctor No (1962). So successful was the Bond franchise that the screen became deluged with carbon copies of Fleming’s hero. James Bond is the anti-Sherlock, a gadget-toting girl-seducing sophisticated secret agent who only seems to show any ingenuity when in a brawl or in a bed. Suffice to say that in a world of beds, breasts and bad language, Holmes has no place so, since the start of this permissiveness, the straightforward Sherlock Holmes movie has become a rare animal indeed.

The idea behind A Study In Terror (1965) was certainly inspired – pitting the world’s greatest detective against the world’s most fiendish serial killer, Jack The Ripper. It seems strange that no-one had ever considered bringing about this confrontation before – while the Ripper was committing atrocities upon unfortunate prostitutes in 1888, Holmes was working on the Baskerville case. It was also the very first X-rated Holmes movie, awarded not for any horror content as such, but for the sexual elements implicit in the plot. The film opens during Jack The Ripper’s reign of terror in London’s East End, where two street women have already met gruesome deaths, and a third is to die before the great detective becomes involved with the murders, and he does so in an unusual way. Holmes (John Neville) receives an anonymous package with a Whitechapel postmark, containing a case of surgical instruments with the postmortem scalpel missing. As Holmes scrutinises the case, Watson (Donald Houston) asks if it tells him anything:

The idea behind A Study In Terror (1965) was certainly inspired – pitting the world’s greatest detective against the world’s most fiendish serial killer, Jack The Ripper. It seems strange that no-one had ever considered bringing about this confrontation before – while the Ripper was committing atrocities upon unfortunate prostitutes in 1888, Holmes was working on the Baskerville case. It was also the very first X-rated Holmes movie, awarded not for any horror content as such, but for the sexual elements implicit in the plot. The film opens during Jack The Ripper’s reign of terror in London’s East End, where two street women have already met gruesome deaths, and a third is to die before the great detective becomes involved with the murders, and he does so in an unusual way. Holmes (John Neville) receives an anonymous package with a Whitechapel postmark, containing a case of surgical instruments with the postmortem scalpel missing. As Holmes scrutinises the case, Watson (Donald Houston) asks if it tells him anything:

“To start with the obvious, these instruments belong to a medical man who has descended to hard times. The instruments of one’s trade are always the last things to be pawned. Observe this speck of white – silver polish. No surgeon would ever clean his instruments with silver polish. They’ve been treated like common cutlery by someone concerned only with their appearance. This is substantiated by these chalk marks, they relate to the pawn ticket number. If the pawnbroker had thought they were stolen he would never have displayed them in a window. The shop faces south in a narrow street and business is bad. I should also add that the pawnbroker is a foreigner. Observe how the material has faded here – the sun has touched the inside of the case only when at its height and able to shine over the roofs of the buildings opposite, hence the shop is in a narrow street facing south, and business had to be bad for the case to remain undisturbed for so long.” Watson asks how he can be so sure the pawnbroker is a foreigner. “The seven in the pledge number is crossed in the Continental manner.”

“To start with the obvious, these instruments belong to a medical man who has descended to hard times. The instruments of one’s trade are always the last things to be pawned. Observe this speck of white – silver polish. No surgeon would ever clean his instruments with silver polish. They’ve been treated like common cutlery by someone concerned only with their appearance. This is substantiated by these chalk marks, they relate to the pawn ticket number. If the pawnbroker had thought they were stolen he would never have displayed them in a window. The shop faces south in a narrow street and business is bad. I should also add that the pawnbroker is a foreigner. Observe how the material has faded here – the sun has touched the inside of the case only when at its height and able to shine over the roofs of the buildings opposite, hence the shop is in a narrow street facing south, and business had to be bad for the case to remain undisturbed for so long.” Watson asks how he can be so sure the pawnbroker is a foreigner. “The seven in the pledge number is crossed in the Continental manner.”

It would seem from this elaborate piece of deduction that Holmes is in fine form and the screenwriters have captured the true flavour of Arthur Conan Doyle. Unfortunately this standard is not easily maintained and the rest of the film fails to match this fine exposition. Holmes finds the Osborne coat-of-arms under the felt lining of the box and decides to pay a visit to the head of this noble family (Barry Jones), who recognises the box of instruments as belonging to his eldest son Michael whom he has disowned. As they leave they bump into the Duke’s younger son, Lord Carfax (John Fraser), who confirms that the instruments belong to his brother who disappeared soon after graduating. Holmes’ next move is to seek out the Whitechapel pawnshop which is found, as predicted, in a narrow street facing south. Here he learns that the instruments were pawned by a woman named Angela Osborne, giving her address as an East End hostel.

It would seem from this elaborate piece of deduction that Holmes is in fine form and the screenwriters have captured the true flavour of Arthur Conan Doyle. Unfortunately this standard is not easily maintained and the rest of the film fails to match this fine exposition. Holmes finds the Osborne coat-of-arms under the felt lining of the box and decides to pay a visit to the head of this noble family (Barry Jones), who recognises the box of instruments as belonging to his eldest son Michael whom he has disowned. As they leave they bump into the Duke’s younger son, Lord Carfax (John Fraser), who confirms that the instruments belong to his brother who disappeared soon after graduating. Holmes’ next move is to seek out the Whitechapel pawnshop which is found, as predicted, in a narrow street facing south. Here he learns that the instruments were pawned by a woman named Angela Osborne, giving her address as an East End hostel.

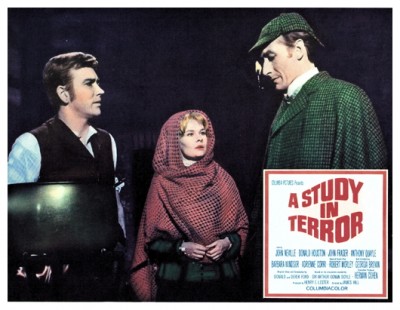

The hostel, which incorporates a soup kitchen and a small hospital, is run by Doctor Murray (Anthony Quayle) aided by his niece Sally (Judi Dench) and is financed by Lord Carfax. Holmes tells Watson go to the soup kitchen to make enquiries. Acting on Holmes instructions, Watson makes a scene at the soup kitchen when Doctor Murray and Sally deny knowing the Osborne woman. Meanwhile the detective, disguised as an old tramp, watches the proceedings keenly. After Watson exits, Sally leaves hurriedly, followed by the disguised Holmes. He follows her to a small house to find Lord Carfax. Holmes throws off his disguise and asks Carfax for the whole story, who admits to being blackmailed by Max Steiner (Peter Carsten), owner of the Angel And Crown pub. It’s learned that Michael had married a prostitute and Steiner threatened to go to the newspapers with the scandal. Holmes visits the pub to confront Steiner and demand the whereabouts of Angela Osborne, but Steiner insists he has no idea where she is.

The hostel, which incorporates a soup kitchen and a small hospital, is run by Doctor Murray (Anthony Quayle) aided by his niece Sally (Judi Dench) and is financed by Lord Carfax. Holmes tells Watson go to the soup kitchen to make enquiries. Acting on Holmes instructions, Watson makes a scene at the soup kitchen when Doctor Murray and Sally deny knowing the Osborne woman. Meanwhile the detective, disguised as an old tramp, watches the proceedings keenly. After Watson exits, Sally leaves hurriedly, followed by the disguised Holmes. He follows her to a small house to find Lord Carfax. Holmes throws off his disguise and asks Carfax for the whole story, who admits to being blackmailed by Max Steiner (Peter Carsten), owner of the Angel And Crown pub. It’s learned that Michael had married a prostitute and Steiner threatened to go to the newspapers with the scandal. Holmes visits the pub to confront Steiner and demand the whereabouts of Angela Osborne, but Steiner insists he has no idea where she is.

The Prime Minister (Cecil Parker), concerned by the political implications of the horrors of Whitechapel, instructs Mycroft Holmes (Robert Morley) to enlist the services of his brother in order to bring Jack The Ripper to justice. While Mycroft is trying to persuade Sherlock to help, Inspector Lestrade (Frank Finlay) bursts into the room with a letter written by the murderer: “Dear Boss, I keep hearing that the police have caught me, but they won’t fix me yet. I have to laugh when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. I am down on whores, and won’t rest until I do get buckled. I love my work and want to start again. My knife is nice and sharp. I want to get to work right away. Good luck. Yours truly, Jack The Ripper.”

The Prime Minister (Cecil Parker), concerned by the political implications of the horrors of Whitechapel, instructs Mycroft Holmes (Robert Morley) to enlist the services of his brother in order to bring Jack The Ripper to justice. While Mycroft is trying to persuade Sherlock to help, Inspector Lestrade (Frank Finlay) bursts into the room with a letter written by the murderer: “Dear Boss, I keep hearing that the police have caught me, but they won’t fix me yet. I have to laugh when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. I am down on whores, and won’t rest until I do get buckled. I love my work and want to start again. My knife is nice and sharp. I want to get to work right away. Good luck. Yours truly, Jack The Ripper.”

The letter is a precursor to another gruesome murder. Present at the autopsy, Holmes suggests, “A medical student perhaps? It’s true these murders are the work of a madman, but a madman with certain medical skills, considerable intelligence and education. Take that letter, the punctuation was exact. The grammar and syntax, though cleverly concealed, were the work of an intelligent man and, to a graphologist, it was obvious that the writing was deliberately scrawled. We must not take the mask for the face!” Eventually Murray admits he knows the whereabouts of Michael Osborne (John Cairney). The doctor discloses that Michael worked in the surgery with him and one night, when Angela and Steiner had attempted to involve Michael in the blackmail plot, a fight broke out in which a bottle of acid was thrown at Angela’s face. Murray did what he could to save her face, and a week later Steiner took her away, never to be seen again.

The letter is a precursor to another gruesome murder. Present at the autopsy, Holmes suggests, “A medical student perhaps? It’s true these murders are the work of a madman, but a madman with certain medical skills, considerable intelligence and education. Take that letter, the punctuation was exact. The grammar and syntax, though cleverly concealed, were the work of an intelligent man and, to a graphologist, it was obvious that the writing was deliberately scrawled. We must not take the mask for the face!” Eventually Murray admits he knows the whereabouts of Michael Osborne (John Cairney). The doctor discloses that Michael worked in the surgery with him and one night, when Angela and Steiner had attempted to involve Michael in the blackmail plot, a fight broke out in which a bottle of acid was thrown at Angela’s face. Murray did what he could to save her face, and a week later Steiner took her away, never to be seen again.

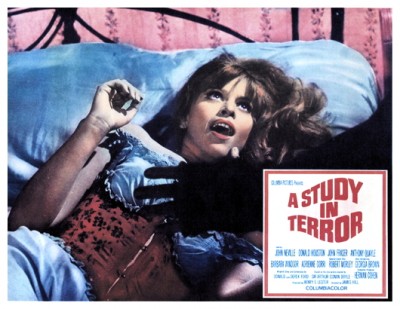

Murray leads Holmes to a small room in the hostel where an inarticulate simpleton is seen cowering in a corner. “You wanted Michael Osborne? Here he is. Whether it was Steiner’s blows to the head, or whether his mind could suffer no more of the world his wife had shown him, I don’t know, but this is how he’s been since that night.” Holmes pieces together the remainder of the story when he confronts Angela Osborne (Adrienne Corri), horribly disfigured and leading an existence of total seclusion in a single room above the Angel And Crown pub. The next day Holmes and Watson, with Lord Carfax, take the demented Michael back to his ancestral family home, after which the detective confides to Watson that the last act of Jack The Ripper is about to commence. That night the Ripper slips into Angela’s room and is about to stab her, when Holmes steps out from the shadows: “Good evening Lord Carfax!” As the Ripper attacks Holmes an oil lamp is overturned starting a fire which engulfs the Ripper along with Angela and Steiner, while Holmes escapes unharmed.

Murray leads Holmes to a small room in the hostel where an inarticulate simpleton is seen cowering in a corner. “You wanted Michael Osborne? Here he is. Whether it was Steiner’s blows to the head, or whether his mind could suffer no more of the world his wife had shown him, I don’t know, but this is how he’s been since that night.” Holmes pieces together the remainder of the story when he confronts Angela Osborne (Adrienne Corri), horribly disfigured and leading an existence of total seclusion in a single room above the Angel And Crown pub. The next day Holmes and Watson, with Lord Carfax, take the demented Michael back to his ancestral family home, after which the detective confides to Watson that the last act of Jack The Ripper is about to commence. That night the Ripper slips into Angela’s room and is about to stab her, when Holmes steps out from the shadows: “Good evening Lord Carfax!” As the Ripper attacks Holmes an oil lamp is overturned starting a fire which engulfs the Ripper along with Angela and Steiner, while Holmes escapes unharmed.

Finally Watson asks Holmes how he knew Lord Carfax was Jack The Ripper. “His medical knowledge. When I dropped the case of instruments in his father’s house, he picked it up. You remember that, Watson? Did you not notice that he immediately put the instruments in their right niches. How odd, I thought, how interesting, a layman might ponder for a moment, but Carfax did not hesitate. There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact, Watson, but what was most obvious and revealing was the letter. The writer described his murders as work – I love my work, I want to get to work right away – if his gruesome activity was, as he said it was, his work, he was obviously a man of means who had no need of ordinary employment. Doctor Murray, who works very hard, would have written perhaps ‘pastime’ – I ruled out Murray. When I investigated the Osborne family I found insanity through four generations. Carfax’s reason hung on a thread. That his brother should put the name of Osborne to a common prostitute, and that she should carry that name to the street corners of Whitechapel, broke that thread. Carfax was protecting – insanely – the family name. He’d never seen Angela, but it seemed logical to him – mad to us – that he could kill her by a process of elimination. He searched for her with his knife from one prostitute to the next. Lestrade and the police do not know the identity of Jack The Ripper, no useful purpose will ever be served by disclosing his identity now. The Osborne family have suffered enough as it is, Lestrade has his three buckets of ash, but we will keep the name.”

Finally Watson asks Holmes how he knew Lord Carfax was Jack The Ripper. “His medical knowledge. When I dropped the case of instruments in his father’s house, he picked it up. You remember that, Watson? Did you not notice that he immediately put the instruments in their right niches. How odd, I thought, how interesting, a layman might ponder for a moment, but Carfax did not hesitate. There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact, Watson, but what was most obvious and revealing was the letter. The writer described his murders as work – I love my work, I want to get to work right away – if his gruesome activity was, as he said it was, his work, he was obviously a man of means who had no need of ordinary employment. Doctor Murray, who works very hard, would have written perhaps ‘pastime’ – I ruled out Murray. When I investigated the Osborne family I found insanity through four generations. Carfax’s reason hung on a thread. That his brother should put the name of Osborne to a common prostitute, and that she should carry that name to the street corners of Whitechapel, broke that thread. Carfax was protecting – insanely – the family name. He’d never seen Angela, but it seemed logical to him – mad to us – that he could kill her by a process of elimination. He searched for her with his knife from one prostitute to the next. Lestrade and the police do not know the identity of Jack The Ripper, no useful purpose will ever be served by disclosing his identity now. The Osborne family have suffered enough as it is, Lestrade has his three buckets of ash, but we will keep the name.”

This contrived and rather unconvincing exposition brings the film to a close. The script certainly has its merits and it’s commendable how writers Donald Ford and Derek Ford blend the authentic details of the Ripper murders with the fictitious plot but, in general, its convoluted path is detrimental to its effectiveness. The producers wanted to present the detective in a new light, insisting that he was no longer the old fuddy-duddy Holmes: “He’s now way-out and with it!” It can be dangerous to tamper with legendary characters – the last thing Conan Doyle’s character would wish to be is ‘with it’ and this particular experiment fails, lacking the mystic authority and towering intellectualism that the character demands.

This contrived and rather unconvincing exposition brings the film to a close. The script certainly has its merits and it’s commendable how writers Donald Ford and Derek Ford blend the authentic details of the Ripper murders with the fictitious plot but, in general, its convoluted path is detrimental to its effectiveness. The producers wanted to present the detective in a new light, insisting that he was no longer the old fuddy-duddy Holmes: “He’s now way-out and with it!” It can be dangerous to tamper with legendary characters – the last thing Conan Doyle’s character would wish to be is ‘with it’ and this particular experiment fails, lacking the mystic authority and towering intellectualism that the character demands.

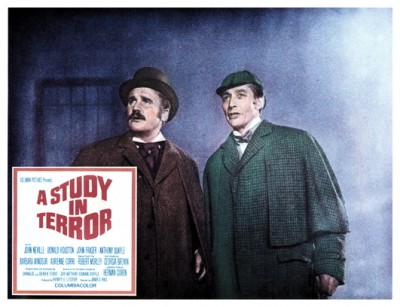

Holmes is played by John Neville, an experienced and well-respected stage performer who may be best remembered as the lead in Terry Gilliam‘s version of The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen (1988) or as ‘The Well-Manicured Man’, one of the lead conspirators in The X-Files (1998). Despite Neville’s skill and care, his Holmes is little more than a caricature. Although suitably gaunt, Neville’s face and hairstyle seem far too modern to be effective, and his dialogue is so devoid of period feeling that it jars. Holmes and Watson’s relationship is never really established, partly due to the interpretation of Watson by Donald Houston who has both feet firmly in the Nigel Bruce camp with a blushing bashfulness reminiscent of Oliver Hardy. So many filmmakers seem compelled to present Holmes and Watson as a double-act with Holmes as the straight man and Watson as the comedy relief, failing to establish the essential relationship between the two men as portrayed in the books.

Holmes is played by John Neville, an experienced and well-respected stage performer who may be best remembered as the lead in Terry Gilliam‘s version of The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen (1988) or as ‘The Well-Manicured Man’, one of the lead conspirators in The X-Files (1998). Despite Neville’s skill and care, his Holmes is little more than a caricature. Although suitably gaunt, Neville’s face and hairstyle seem far too modern to be effective, and his dialogue is so devoid of period feeling that it jars. Holmes and Watson’s relationship is never really established, partly due to the interpretation of Watson by Donald Houston who has both feet firmly in the Nigel Bruce camp with a blushing bashfulness reminiscent of Oliver Hardy. So many filmmakers seem compelled to present Holmes and Watson as a double-act with Holmes as the straight man and Watson as the comedy relief, failing to establish the essential relationship between the two men as portrayed in the books.

The cast of A Study In Terror also includes Frank Finlay who is suitably thick-skulled and rat-faced as Inspector Lestrade, a role he would return to play in the seventies remake Murder By Decree (1979). Robert Morley gives a pleasant performance as Sherlock’s smarter brother Mycroft. Morley’s rotund appearance fits exactly Conan Doyle’s description of the character: “His body was absolutely corpulent but his face, though massive, had preserved something of the sharpness of expression which was so remarkable in that of his brother.” Barbara Windsor, who plays the doomed Annie Chapman, is famous for her roles in the long-running British soap-opera East Enders and more than a dozen Carry On films starting with Carry On Spying (1964). Judi Dench, over the next two decades, established herself as one of the most significant British theatre performers ever and, on television, she achieved success in the series A Fine Romance and As Time Goes By. Her film appearances were infrequent until she was cast as ‘M’ in GoldenEye (1995), a role she continued to play in James Bond films through to Skyfall (2012).

The cast of A Study In Terror also includes Frank Finlay who is suitably thick-skulled and rat-faced as Inspector Lestrade, a role he would return to play in the seventies remake Murder By Decree (1979). Robert Morley gives a pleasant performance as Sherlock’s smarter brother Mycroft. Morley’s rotund appearance fits exactly Conan Doyle’s description of the character: “His body was absolutely corpulent but his face, though massive, had preserved something of the sharpness of expression which was so remarkable in that of his brother.” Barbara Windsor, who plays the doomed Annie Chapman, is famous for her roles in the long-running British soap-opera East Enders and more than a dozen Carry On films starting with Carry On Spying (1964). Judi Dench, over the next two decades, established herself as one of the most significant British theatre performers ever and, on television, she achieved success in the series A Fine Romance and As Time Goes By. Her film appearances were infrequent until she was cast as ‘M’ in GoldenEye (1995), a role she continued to play in James Bond films through to Skyfall (2012).

Not all the reviews for A Study In Terror were negative. It was well-received in the USA and regarded by one critic as a snappy handsomely mounted production. Another critic thought Neville made the best screen Sherlock yet. Despite these positive reviews it failed to impress at the box-office and proved to be the first and final film for Compton Productions. As well as spending an above-average amount on the project, they went all-out in their promotional campaign, producing giant-sized press books, posters and folders. It was to be the first of a new franchise of Holmes adventures authorised by the Conan Doyle estate, but its failure at the box-office put an end to these exciting and ambitious plans.

Not all the reviews for A Study In Terror were negative. It was well-received in the USA and regarded by one critic as a snappy handsomely mounted production. Another critic thought Neville made the best screen Sherlock yet. Despite these positive reviews it failed to impress at the box-office and proved to be the first and final film for Compton Productions. As well as spending an above-average amount on the project, they went all-out in their promotional campaign, producing giant-sized press books, posters and folders. It was to be the first of a new franchise of Holmes adventures authorised by the Conan Doyle estate, but its failure at the box-office put an end to these exciting and ambitious plans.

Not only did the failure of A Study In Terror deny Holmes fans further new adventures of the world’s greatest detective, but it also revealed how risky Holmes had become as a film subject, which is why there have been so few straightforward Sherlock Holmes movies since. Right now I’d like to profusely thank author and detective historian Paul W. Fairman for his assistance in researching this article, and inform you that it’s vitally important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because my horoscope said that if you don’t read all my reviews from now on, the Earth would be destroyed by a disaster of biblical proportions, you know, real wrath-of-God type stuff: Fire and brimstone coming down from the skies, rivers and seas boiling, forty years of darkness, earthquakes, volcanoes, the dead rising from the grave, human sacrifice – you get the picture. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but I read it on the internet, so it must be true. So sleep well and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you visiting Horror News every week! Toodles!

Not only did the failure of A Study In Terror deny Holmes fans further new adventures of the world’s greatest detective, but it also revealed how risky Holmes had become as a film subject, which is why there have been so few straightforward Sherlock Holmes movies since. Right now I’d like to profusely thank author and detective historian Paul W. Fairman for his assistance in researching this article, and inform you that it’s vitally important that you join me for next week’s edition of Horror News, because my horoscope said that if you don’t read all my reviews from now on, the Earth would be destroyed by a disaster of biblical proportions, you know, real wrath-of-God type stuff: Fire and brimstone coming down from the skies, rivers and seas boiling, forty years of darkness, earthquakes, volcanoes, the dead rising from the grave, human sacrifice – you get the picture. Normally I’m highly skeptical of such claims, but I read it on the internet, so it must be true. So sleep well and remember, the survival of the entire world depends on you visiting Horror News every week! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews