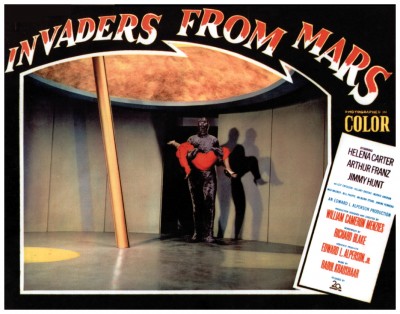

“One night, young David McLean sees a spaceship crash into a nearby sandpit. His father goes to investigate, but comes back changed. Where once he was cheerful and affectionate, he’s now sullen and snarlingly rude. Others fall into the sandpit and begin acting like him: cold, ill-tempered and conspiratorial. David knows that aliens are taking over the bodies of humans, but he’ll soon discover there have been far more of these terrible thefts than he could have imagined. The young doom-monger finds some serious help in a lady doctor and a brilliant astronomer. Soon they meet the aliens: green creatures with insect-like eyes. These beings prove to be slaves to their leader: a large, silent head with ceaselessly shifting eyes and two tentacles on either side, each of which branches off into three smaller tentacles. It’s up to the redoubtable earth trio to stop its evil plans.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Genre cinema has always been better able to cope with horror to which imagery and atmosphere is central, than with science fiction which, in its literary form, relies on quite complex intellectual structures. But there is one extremely common thought-structure in science fiction cinema that is paradoxically unusual in science fiction literature: science itself is not to be trusted. again and again the scientist is seen as somebody who unleashes horrors on the world, or conversely is quite unable to deal with horrors that already exist because he over-intellectualises. Meanwhile the military, for example, steps in and takes direct action. Thus we have the situation where science fiction movies are fundamentally conservative (there are exceptions of course), to the point where science fiction becomes just another form of Gothic. Instead of Gothic being equated with irrational forces, and science fiction with rational forces, the cinema conventionally sees both genres as dealing with creatures of darkness, and science as just another form of magic.

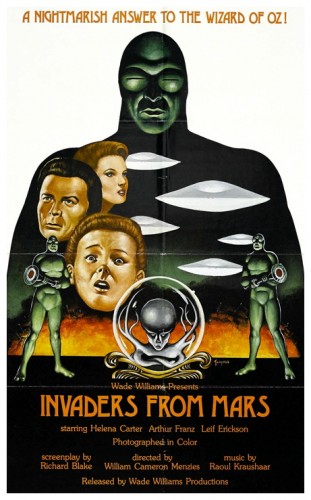

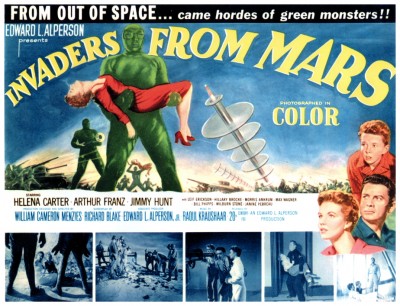

All of this may be a salutary reminder to us that we should not necessarily put our faith in men in white coats, and it was a very natural reminder in an age where the primary miracle of science seemed to be the atomic bomb, but it also contributed to the paranoia of modern life and this paranoia reached its peak in the fifties, when our loved ones became the monsters, in films like It Came From Outer Space (1953), Invasion Of The Body Snatchers (1956) and I Married A Monster From Outer Space (1958). The first of these was a small-scale film essentially made for children entitled Invaders From Mars (1953), directed by William Cameron Menzies – who had made the big-budget film Things To Come (1936) – and released in May of 1953.

All of this may be a salutary reminder to us that we should not necessarily put our faith in men in white coats, and it was a very natural reminder in an age where the primary miracle of science seemed to be the atomic bomb, but it also contributed to the paranoia of modern life and this paranoia reached its peak in the fifties, when our loved ones became the monsters, in films like It Came From Outer Space (1953), Invasion Of The Body Snatchers (1956) and I Married A Monster From Outer Space (1958). The first of these was a small-scale film essentially made for children entitled Invaders From Mars (1953), directed by William Cameron Menzies – who had made the big-budget film Things To Come (1936) – and released in May of 1953.

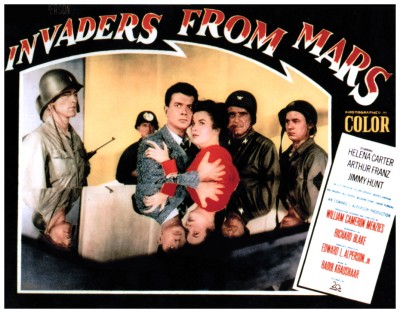

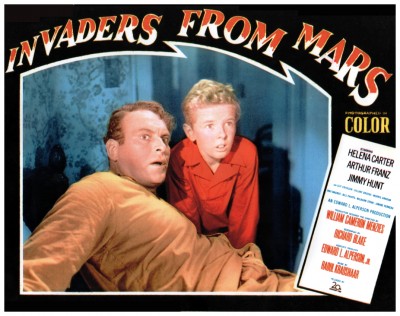

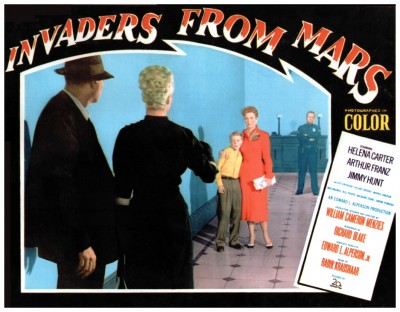

A small boy (Jimmy Hunt) wakes up at night to see a flying saucer arrive and burrow into the ground in his expansive back yard. The next day his father (Leif Erickson) goes to investigate and comes back oddly changed, emotionally remote and rather violent, with a strange mark on the back of his neck. All of this is filmed from a child’s-eye view with adults tend to loom rather menacingly. The boy goes to the police, only to find that the police chief (Bert Freed) has the same mark on the back of his neck. The nightmare continues when his mother (Hillary Brooke) arrives, similarly cold and alien. In fact the psychological reverberations of this image go deep – it is surely a fundamental fear that a person’s nearest and dearest are basically alien, that they have no love for you, that they belong to another world that you can never join.

A small boy (Jimmy Hunt) wakes up at night to see a flying saucer arrive and burrow into the ground in his expansive back yard. The next day his father (Leif Erickson) goes to investigate and comes back oddly changed, emotionally remote and rather violent, with a strange mark on the back of his neck. All of this is filmed from a child’s-eye view with adults tend to loom rather menacingly. The boy goes to the police, only to find that the police chief (Bert Freed) has the same mark on the back of his neck. The nightmare continues when his mother (Hillary Brooke) arrives, similarly cold and alien. In fact the psychological reverberations of this image go deep – it is surely a fundamental fear that a person’s nearest and dearest are basically alien, that they have no love for you, that they belong to another world that you can never join.

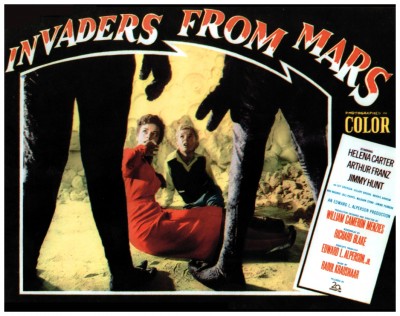

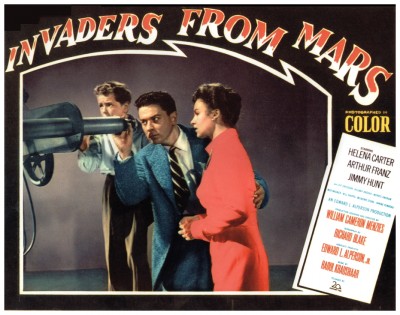

Finally he succeeds in convincing a woman doctor (Helena Carter) and an astronomer (Arthur Franz), and they call in the army. They locate the aliens in a labyrinth of tunnels underneath the town, there is a battle and the invaders are destroyed, including their ruler who proves to be a disembodied head in a glass sphere. In the American version of the film, the closing sequence reveals that it was only a dream – apparently a recurring dream, for the saucer lands again at the very end. In the European version this material was cut, and the story is told as ‘real’. The film has some wonderful moments, and indeed a kind of dream-like quality throughout (the back yard is like a picture from a story-book). A very good moment is the opening up of the sand to reveal the Martian lair beneath, into which the boy and his doctor friend both fall. The original screenwriter, John Tucker Battle, was so furious when the dream ending was added that he had his name removed from the credits, but in some ways it fits the unearthly quality of the story.

Finally he succeeds in convincing a woman doctor (Helena Carter) and an astronomer (Arthur Franz), and they call in the army. They locate the aliens in a labyrinth of tunnels underneath the town, there is a battle and the invaders are destroyed, including their ruler who proves to be a disembodied head in a glass sphere. In the American version of the film, the closing sequence reveals that it was only a dream – apparently a recurring dream, for the saucer lands again at the very end. In the European version this material was cut, and the story is told as ‘real’. The film has some wonderful moments, and indeed a kind of dream-like quality throughout (the back yard is like a picture from a story-book). A very good moment is the opening up of the sand to reveal the Martian lair beneath, into which the boy and his doctor friend both fall. The original screenwriter, John Tucker Battle, was so furious when the dream ending was added that he had his name removed from the credits, but in some ways it fits the unearthly quality of the story.

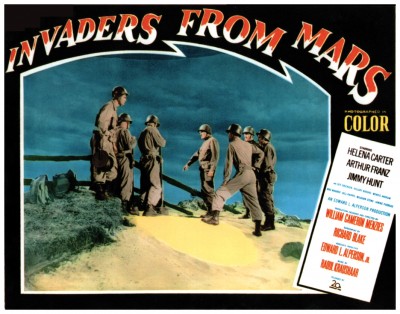

We are treated to loads of stock footage of trains transporting American soldiers off to combat the aliens, with tanks galore on display, and yet the film’s most positive character is an open-minded astronomer who brings grist to the liberal mill. He tells us America has constructed a rocket that will lead to building space stations armed with nuclear weapons ready to destroy any enemy. He interprets this situation not just as self-defence but as a threat to the Martians whose race is thus endangered. Invaders From Mars echoes the liberal content of The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) and also the hysterical content of Invasion USA (1952). A openly anti-Soviet message, complete with the need for security, coexists uneasily here with a call for understanding.

We are treated to loads of stock footage of trains transporting American soldiers off to combat the aliens, with tanks galore on display, and yet the film’s most positive character is an open-minded astronomer who brings grist to the liberal mill. He tells us America has constructed a rocket that will lead to building space stations armed with nuclear weapons ready to destroy any enemy. He interprets this situation not just as self-defence but as a threat to the Martians whose race is thus endangered. Invaders From Mars echoes the liberal content of The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) and also the hysterical content of Invasion USA (1952). A openly anti-Soviet message, complete with the need for security, coexists uneasily here with a call for understanding.

Kids will surely enjoy this film but, considering its twist ending that sends the boy back into his continuous nightmare, this must one of the most depressing and scariest films ever intended for children. The film is the realisation of a childhood nightmare, a world where all the adults become frightening enemies, even one’s own parents. A sort of catharsis occurs when the army moves in and fights the Martians but at the end of the film, when the whole terrible dream starts again, this proves to be illusory, and one realises that the character is trapped in his nightmare forever. The film was made on a very small budget but this handicap actually worked in favour of maintaining the dream-like atmosphere striven by Menzies. The landing of the saucer in the back yard was all done on a soundstage, the hill being nothing but a mound of sand made to appear larger through forced perspective.

Kids will surely enjoy this film but, considering its twist ending that sends the boy back into his continuous nightmare, this must one of the most depressing and scariest films ever intended for children. The film is the realisation of a childhood nightmare, a world where all the adults become frightening enemies, even one’s own parents. A sort of catharsis occurs when the army moves in and fights the Martians but at the end of the film, when the whole terrible dream starts again, this proves to be illusory, and one realises that the character is trapped in his nightmare forever. The film was made on a very small budget but this handicap actually worked in favour of maintaining the dream-like atmosphere striven by Menzies. The landing of the saucer in the back yard was all done on a soundstage, the hill being nothing but a mound of sand made to appear larger through forced perspective.

The film turns out to be a dream, but even this is open to two radically different interpretations. Given that the dreamer is a little boy, we could argue that this is proof that even youngsters are aware of the dangers of a Communist takeover. But his parents are among the first victims of the Martians – they change from being loving and caring to brutal and repressive. Most interesting of all is how the boy finds substitute parents in the astronomer and the doctor, and a surrogate father – a Colonel (Morris Ankrum), representative of authority in every sense. The film unconsciously reflects the function of the home and family life in the fifties and the determination on the part of the ruling elite to reinforce these values. The little hero’s nightmare therefore indicates that all was not well in America’s suburbia at that time.

The film turns out to be a dream, but even this is open to two radically different interpretations. Given that the dreamer is a little boy, we could argue that this is proof that even youngsters are aware of the dangers of a Communist takeover. But his parents are among the first victims of the Martians – they change from being loving and caring to brutal and repressive. Most interesting of all is how the boy finds substitute parents in the astronomer and the doctor, and a surrogate father – a Colonel (Morris Ankrum), representative of authority in every sense. The film unconsciously reflects the function of the home and family life in the fifties and the determination on the part of the ruling elite to reinforce these values. The little hero’s nightmare therefore indicates that all was not well in America’s suburbia at that time.

But the eerie atmosphere was chiefly created by the sets, all of which were subtly distorted, suggesting menace in every angle and shadow. In many ways, with its child’s point-of-view of a frightening world, the film is reminiscent of The Night Of The Hunter (1955) directed by Charles Laughton. Invaders From Mars can hardly be described as a great science fiction film, but enough originality went into its making to lift it out of the category of simple schlock. Hold that thought for the next seven days, and I’ll ask you to please join me again next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

But the eerie atmosphere was chiefly created by the sets, all of which were subtly distorted, suggesting menace in every angle and shadow. In many ways, with its child’s point-of-view of a frightening world, the film is reminiscent of The Night Of The Hunter (1955) directed by Charles Laughton. Invaders From Mars can hardly be described as a great science fiction film, but enough originality went into its making to lift it out of the category of simple schlock. Hold that thought for the next seven days, and I’ll ask you to please join me again next week when I throw you another bone of contention and harrow you to the marrow with another blood-curdling excursion through the darkest dank streets of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews