“After the death of his Nobel Prize-winning father, billionaire physicist Jerry Cornelius becomes embroiled in the search for the mysterious ‘Final programme’ developed by his father. The programme, a design for a perfect, self-replicating human being, is contained on microfilm. A group of scientists, led by the formidable Miss Brunner (who literally consumes her lovers), has sought Cornelius’s help in obtaining it. After a chase across a war-torn Europe on the verge of anarchy, Brunner and Cornelius obtain the microfilm from Jerry’s loathsome brother Frank. They proceed to an abandoned underground Nazi fortress in the Arctic to run the programme, with Jerry and Miss Brunner as the subjects.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

1973 was a formative year for genre films, introducing a new generation of not only films and filmmakers, but entirely new styles and genres: The Exorcist (1973) represented Hollywood’s first real venture into big-budget horror; Violent cops like Serpico (1973) were unleashed upon an unsuspecting world; Roger Moore’s first outing as the up-to-date James Bond in Live And Let Die (1973); Enter The Dragon (1973) introduced the Chop-Socky genre to the American mainstream; and with American Graffiti (1973) George Lucas kick-started a wave of nostalgia that can still be felt today. There were many other great films showing us the new direction cinema was about to take: The Sting (1973), Papillion (1973), The Last Tango In Paris (1973), Paper Moon (1973), the list goes on.

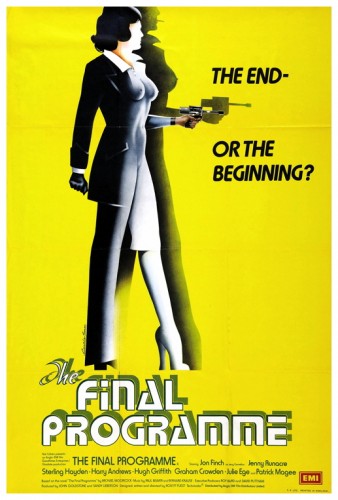

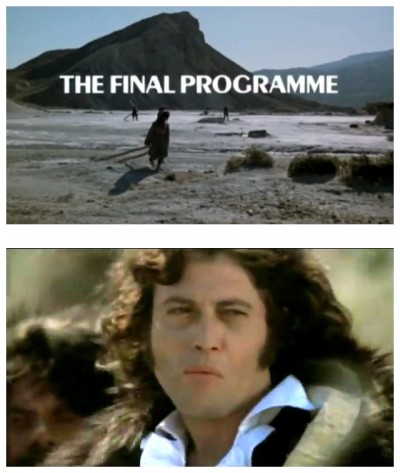

There were also films still being made that visually and stylistically belonged to the previous decade, one of these being the less-than-satisfactory adaptation of The Final Programme (1973) released in the United States as The Last Days Of Man On Earth, presumably because American distributors didn’t want to deal with the English spelling of the word ‘Programme’. It was written and directed by Robert Fuest, a former set designer who had gone from directing colour episodes of The Avengers television series, to The Abominable Doctor Phibes (1971) and Doctor Phibes Rises Again (1972). It wasn’t until he made The Devil’s Rain (1975) that he had really caught up with the seventies, and by that time it was too little too late. The Final Programme was based on the novel by Michael Moorc**k, one of Britain’s most innovative science fiction writers (although Moorc**k prefers to call it Speculative Fiction) and features one of Moorc**k’s most famous creations, Jerry Cornelius, a multi-faceted, multi-purpose character who embodies many of the prevalent myths of the 20th century: He’s rich, he’s a rock star, a mercenary, a mystic, a scientist, a secret agent, a Christ figure and many other things beside.

There were also films still being made that visually and stylistically belonged to the previous decade, one of these being the less-than-satisfactory adaptation of The Final Programme (1973) released in the United States as The Last Days Of Man On Earth, presumably because American distributors didn’t want to deal with the English spelling of the word ‘Programme’. It was written and directed by Robert Fuest, a former set designer who had gone from directing colour episodes of The Avengers television series, to The Abominable Doctor Phibes (1971) and Doctor Phibes Rises Again (1972). It wasn’t until he made The Devil’s Rain (1975) that he had really caught up with the seventies, and by that time it was too little too late. The Final Programme was based on the novel by Michael Moorc**k, one of Britain’s most innovative science fiction writers (although Moorc**k prefers to call it Speculative Fiction) and features one of Moorc**k’s most famous creations, Jerry Cornelius, a multi-faceted, multi-purpose character who embodies many of the prevalent myths of the 20th century: He’s rich, he’s a rock star, a mercenary, a mystic, a scientist, a secret agent, a Christ figure and many other things beside.

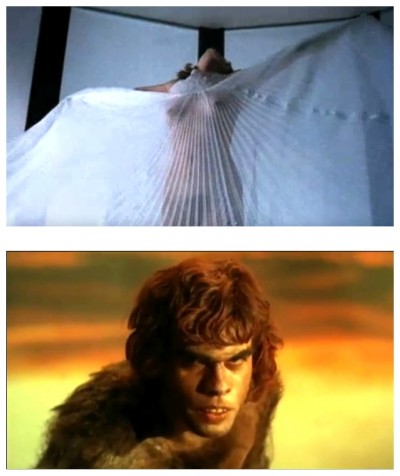

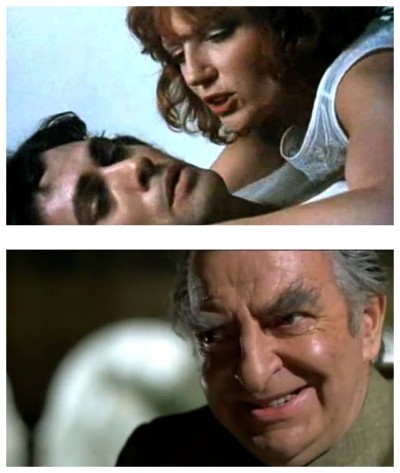

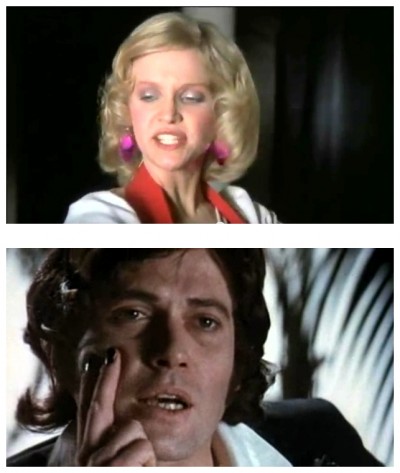

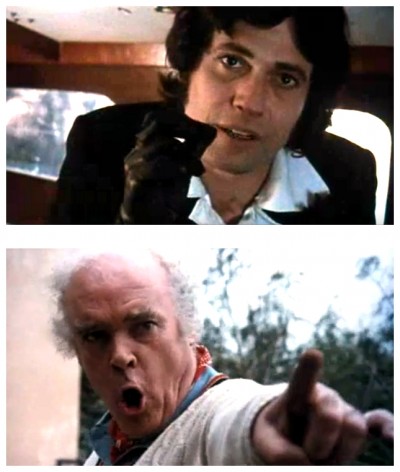

The Final Programme certainly looks impressive but not much of Moorc**k’s unique creation remains. The Cornelius patriarch has passed away, leaving behind some hidden microfilm on which is a mysterious ‘final’ computer programme that contains a number of profoundly important secrets. Apart from Jerry (Jon Finch) there are others involved in the hunt for the microfilm, including his evil brother Frank (Derrick O’Connor), who has kidnapped their sister Catherine (Sarah Douglas) whom Jerry loves in a way that exceeds brotherly affection. There’s also the awesome Miss Brunner (Jenny Runacre), who has a tendency to consume her lovers literally and completely, bones and all. In the novel, the programme serves to combine Jerry and Miss Brunner into one single creature – a bisexual self-replicating Messiah who leads the population of Europe into the Mediterranean in a lemming-like rush to oblivion but, in the film version, their combined bodies form a shaggy neanderthal who winks at the camera, does a Humphrey Bogart impersonation and walks off alone. The film does capture some of the off-beat atmosphere of the book, suggesting a world where reality itself is crumbling around the edges, but overall it falls far short of complete success.

The Final Programme certainly looks impressive but not much of Moorc**k’s unique creation remains. The Cornelius patriarch has passed away, leaving behind some hidden microfilm on which is a mysterious ‘final’ computer programme that contains a number of profoundly important secrets. Apart from Jerry (Jon Finch) there are others involved in the hunt for the microfilm, including his evil brother Frank (Derrick O’Connor), who has kidnapped their sister Catherine (Sarah Douglas) whom Jerry loves in a way that exceeds brotherly affection. There’s also the awesome Miss Brunner (Jenny Runacre), who has a tendency to consume her lovers literally and completely, bones and all. In the novel, the programme serves to combine Jerry and Miss Brunner into one single creature – a bisexual self-replicating Messiah who leads the population of Europe into the Mediterranean in a lemming-like rush to oblivion but, in the film version, their combined bodies form a shaggy neanderthal who winks at the camera, does a Humphrey Bogart impersonation and walks off alone. The film does capture some of the off-beat atmosphere of the book, suggesting a world where reality itself is crumbling around the edges, but overall it falls far short of complete success.

Jon Finch fits the part of Jerry visually but fails to reproduce the infinitely ambiguous character of the novels. It could have been worse – Finch replaced Timothy Dalton at the last minute. More successful is Jenny Runacre as Miss Brunner, who comes on like a force ten hurricane, tossing men around like rag dolls and absorbing her lovers, both male and female, with casual ease. Least impressive is Derrick O’Connor as Frank Cornelius, who lacks the necessary rat-like presence, and an impressive lineup of experienced character actors goes to waste: Sterling Hayden, Harry Andrews, Hugh Griffith, Patrick Magee, Sarah Douglas, Graham Crowden, George Coulouris, Ronald Lacey, Sandra Dickinson.

Jon Finch fits the part of Jerry visually but fails to reproduce the infinitely ambiguous character of the novels. It could have been worse – Finch replaced Timothy Dalton at the last minute. More successful is Jenny Runacre as Miss Brunner, who comes on like a force ten hurricane, tossing men around like rag dolls and absorbing her lovers, both male and female, with casual ease. Least impressive is Derrick O’Connor as Frank Cornelius, who lacks the necessary rat-like presence, and an impressive lineup of experienced character actors goes to waste: Sterling Hayden, Harry Andrews, Hugh Griffith, Patrick Magee, Sarah Douglas, Graham Crowden, George Coulouris, Ronald Lacey, Sandra Dickinson.

Michael Moorc**k was indirectly involved with the making of the film, but he didn’t find it a terribly enjoyable experience. He wasn’t interested in dealing with the film industry because he knew it can be such a depressing business. Sandy Lieberson of Goodtimes Enterprises was very keen on the novel – he had just produced Performance (1970) starring Mick Jagger – and Moorc**k was rather pleased that Lieberson was involved, but he failed to get any financing for it so the project was shelved. A script was written but, as the result was somewhat of a shambles, Lieberson lost interest. Various attempts were made to revive the project but it wasn’t until Robert Fuest became involved and succeeded in raising the finance that filming finally got underway. The following is a transcript of author Michael Moorc**k in conversation with critic John Baxter:

Michael Moorc**k was indirectly involved with the making of the film, but he didn’t find it a terribly enjoyable experience. He wasn’t interested in dealing with the film industry because he knew it can be such a depressing business. Sandy Lieberson of Goodtimes Enterprises was very keen on the novel – he had just produced Performance (1970) starring Mick Jagger – and Moorc**k was rather pleased that Lieberson was involved, but he failed to get any financing for it so the project was shelved. A script was written but, as the result was somewhat of a shambles, Lieberson lost interest. Various attempts were made to revive the project but it wasn’t until Robert Fuest became involved and succeeded in raising the finance that filming finally got underway. The following is a transcript of author Michael Moorc**k in conversation with critic John Baxter:

“Bob Fuest was very keen to work on something, so he elected to do a script and talked EMI into putting up the usual front money, and he wrote a script that appealed to Nat Cohen (then CEO of EMI) and, in a sense, the film would never have got made and I wouldn’t have got any money apart from the original option money if Fuest hadn’t written such an idiot script that appealed to Nat Cohen. So the whole thing started going ahead but Sandy didn’t like the script and asked me to come in on the script conference. I had a look at the script – it was a bad script on anyone’s terms. I began to realise that I knew more about scriptwriting than Fuest did, and up until then I’d been saying, well, you’re the experts, you’re the professionals. So what I did was take the script and I revamped it. I cut out all the reaction shots and tightened it up and I put in a much clearer plot running through it, more than the book had because, as a film, it needed a stronger plot, and I added various visual scenes to amplify it.”

“Bob Fuest was very keen to work on something, so he elected to do a script and talked EMI into putting up the usual front money, and he wrote a script that appealed to Nat Cohen (then CEO of EMI) and, in a sense, the film would never have got made and I wouldn’t have got any money apart from the original option money if Fuest hadn’t written such an idiot script that appealed to Nat Cohen. So the whole thing started going ahead but Sandy didn’t like the script and asked me to come in on the script conference. I had a look at the script – it was a bad script on anyone’s terms. I began to realise that I knew more about scriptwriting than Fuest did, and up until then I’d been saying, well, you’re the experts, you’re the professionals. So what I did was take the script and I revamped it. I cut out all the reaction shots and tightened it up and I put in a much clearer plot running through it, more than the book had because, as a film, it needed a stronger plot, and I added various visual scenes to amplify it.”

“So then I took the script back to them – I only had one copy, all I’d done basically was to work on the original – and Sandy liked it but Fuest said, ‘Well, I’ll take it away and read it’ and Sandy was saying, ‘No, it’s all right, we’ll get it copied first so we can all read it’ and there was this incredible egocentric thing going on all around the table. I didn’t know what half the people there were supposed to be doing at this conference. It was like an old-fashioned satire of a Hollywood script conference with everyone having their own axe to grind, but nobody actually working towards a common end, which I innocently thought we were supposed to be doing. But they were all pissing about, though Lieberson wasn’t, I have to admit. I have a lot of respect for him, a very hard man but he knows what he wants. Anyway, it was finally agreed that Fuest would use my script, and Fuest didn’t like this but he said, ‘Super! Marvelous! We’re all very excited here, Michael!’ and off he went, and when I went down to watch when he started shooting, it began to dawn on me that he was using his original script. He’d actually chucked mine and was using his own script. The result was that he ended up with about three hours of film, two hours of which were primarily reaction shots. All the stuff that I’d crossed out with a pen was back in there. When it came to editing it, of course, it was all out again but by then they had spent thousands of quid shooting it.”

“So then I took the script back to them – I only had one copy, all I’d done basically was to work on the original – and Sandy liked it but Fuest said, ‘Well, I’ll take it away and read it’ and Sandy was saying, ‘No, it’s all right, we’ll get it copied first so we can all read it’ and there was this incredible egocentric thing going on all around the table. I didn’t know what half the people there were supposed to be doing at this conference. It was like an old-fashioned satire of a Hollywood script conference with everyone having their own axe to grind, but nobody actually working towards a common end, which I innocently thought we were supposed to be doing. But they were all pissing about, though Lieberson wasn’t, I have to admit. I have a lot of respect for him, a very hard man but he knows what he wants. Anyway, it was finally agreed that Fuest would use my script, and Fuest didn’t like this but he said, ‘Super! Marvelous! We’re all very excited here, Michael!’ and off he went, and when I went down to watch when he started shooting, it began to dawn on me that he was using his original script. He’d actually chucked mine and was using his own script. The result was that he ended up with about three hours of film, two hours of which were primarily reaction shots. All the stuff that I’d crossed out with a pen was back in there. When it came to editing it, of course, it was all out again but by then they had spent thousands of quid shooting it.”

“None of the actors knew what they were supposed to be doing – and they had a lot of good actors in it. By the time the film was halfway through, the actors were all coming up to me and saying, ‘Look, what the hell is it all about, because he’s not telling us!’ The emphasis of the film kept shifting all the time, because the actors didn’t know if it was supposed to be serious or a James Bond type of film or a take-off or what. The final sequences were, by and large, the best ones. They certainly had a lot more of the spirit of the book, largely because they gave up. Most of the good bits in it were the little cameo parts that the actors did themselves. For instance, that joke fight sequence in the underground cavern between Finch and the villain where Jerry shouts, ‘Miss Brunner, I’m losing!’ and all that sort of stuff. That all came about after Jon Finch and I talked about it. The cast was very good. Jenny Runacre was good as Miss Brunner, but her sister had just died before they started shooting and she reckons she could have done a lot better if it hadn’t been for that. It was quite a good performance but she was under stress at the time. I thought she was the best thing in it really. Jon Finch would have been a lot better if he’d had a clearer idea of what it was all about.”

“None of the actors knew what they were supposed to be doing – and they had a lot of good actors in it. By the time the film was halfway through, the actors were all coming up to me and saying, ‘Look, what the hell is it all about, because he’s not telling us!’ The emphasis of the film kept shifting all the time, because the actors didn’t know if it was supposed to be serious or a James Bond type of film or a take-off or what. The final sequences were, by and large, the best ones. They certainly had a lot more of the spirit of the book, largely because they gave up. Most of the good bits in it were the little cameo parts that the actors did themselves. For instance, that joke fight sequence in the underground cavern between Finch and the villain where Jerry shouts, ‘Miss Brunner, I’m losing!’ and all that sort of stuff. That all came about after Jon Finch and I talked about it. The cast was very good. Jenny Runacre was good as Miss Brunner, but her sister had just died before they started shooting and she reckons she could have done a lot better if it hadn’t been for that. It was quite a good performance but she was under stress at the time. I thought she was the best thing in it really. Jon Finch would have been a lot better if he’d had a clearer idea of what it was all about.”

“As for the ending, it would have been all right in a TV sketch. There’s nothing wrong with the idea, but it had nothing to do with the rest of the picture. Fuest was doing his best to shore it all up by sending up everything that had happened before, because there was no sort of fundamental logic to the structure of the film. A fair amount of my suggestions were used in it, I suppose, odd jokes and things like that. I got about twenty thousand pounds for it which I wouldn’t complain about, but in a sense I really paid dearly for that money. The film screwed me up for a good year, if not longer. The strain of it all and the disappointment at the shambles of it when it came out. There’s something absolutely terrible about a bad version of your stuff, and it affected me very, very badly and quite fundamentally for a long time. When I saw it I sat there willing it to be better but the strain of watching it was just too much. There were one or two sequences involving scientific explanations which, when I first saw them, I literally laughed aloud, they were so ridiculous.”

“As for the ending, it would have been all right in a TV sketch. There’s nothing wrong with the idea, but it had nothing to do with the rest of the picture. Fuest was doing his best to shore it all up by sending up everything that had happened before, because there was no sort of fundamental logic to the structure of the film. A fair amount of my suggestions were used in it, I suppose, odd jokes and things like that. I got about twenty thousand pounds for it which I wouldn’t complain about, but in a sense I really paid dearly for that money. The film screwed me up for a good year, if not longer. The strain of it all and the disappointment at the shambles of it when it came out. There’s something absolutely terrible about a bad version of your stuff, and it affected me very, very badly and quite fundamentally for a long time. When I saw it I sat there willing it to be better but the strain of watching it was just too much. There were one or two sequences involving scientific explanations which, when I first saw them, I literally laughed aloud, they were so ridiculous.”

“I didn’t want the film to do well, I knew it wouldn’t do well. I mean, my faith in the British public would have been badly shattered if it had done well. The thing that counts a lot is the attitude of the distributors towards a film and in this case they actually thought it would do well in the provinces but not in London. Well, it got praised in all the big heavy weekly publications and got really good publicity in London, and if they’d kept it in London they would have probably made money out of it, but they released it first to the provinces and, of course, it did dreadfully. So they didn’t have any confidence in it after that, and quite rightly – it even did badly in France!” And it’s on that rather continental note I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I shall discuss another anti-classic for Horror News. Until then, good night and remember, as my old friend Bela Lugosi would say, “Bevare! Bevare of the big, green dragon that sits on your doorstep – and the gifts it leaves on your lawn.” Toodles!

“I didn’t want the film to do well, I knew it wouldn’t do well. I mean, my faith in the British public would have been badly shattered if it had done well. The thing that counts a lot is the attitude of the distributors towards a film and in this case they actually thought it would do well in the provinces but not in London. Well, it got praised in all the big heavy weekly publications and got really good publicity in London, and if they’d kept it in London they would have probably made money out of it, but they released it first to the provinces and, of course, it did dreadfully. So they didn’t have any confidence in it after that, and quite rightly – it even did badly in France!” And it’s on that rather continental note I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I shall discuss another anti-classic for Horror News. Until then, good night and remember, as my old friend Bela Lugosi would say, “Bevare! Bevare of the big, green dragon that sits on your doorstep – and the gifts it leaves on your lawn.” Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews