SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“A strange new virus has appeared, which only attacks strains of grasses such as wheat and rice, and the world is descending into famine and chaos. Architect John, along with his family and friends, is making his way from London to his brother’s farm in northern England where there will hopefully be food and safety for all of them. Along the way, they encounter hostile soldiers, biker gangs, and all manner of people who are all too willing to take advantage of travelers for a mouthful of food.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Former Hollywood character actor Cornel Wilde spent the late sixties dabbling in directing, resulting in No Blade Of Grass (1970), based on John Christopher‘s excellent first novel The Death Of Grass published in 1956, in which a new virus strain has infected rice crops in Asia causing massive famine. Soon a mutation appears in Europe infecting all types of grasses including wheat and barley.

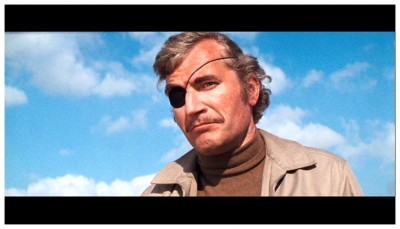

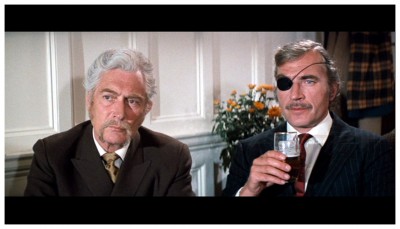

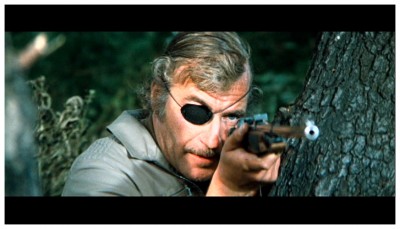

The novel follows the struggles of architect John Custance (Nigel Davenport), his wife (Jean Wallace), daughter (Lynne Frederick) and his friend Roger (John Hamill), as they make their way across an England which is rapidly descending into anarchy, hoping to reach the safety of a potato farm in an isolated valley. After picking up a rather unstable traveling companion named Pirrie (Anthony May), they soon realise they’re going to have to sacrifice many of their morals in order to stay alive. At one point, when their food supply runs out, they kill a family to take their bread. The protagonist justifies this with the belief that, “It was them or us.”

The novel follows the struggles of architect John Custance (Nigel Davenport), his wife (Jean Wallace), daughter (Lynne Frederick) and his friend Roger (John Hamill), as they make their way across an England which is rapidly descending into anarchy, hoping to reach the safety of a potato farm in an isolated valley. After picking up a rather unstable traveling companion named Pirrie (Anthony May), they soon realise they’re going to have to sacrifice many of their morals in order to stay alive. At one point, when their food supply runs out, they kill a family to take their bread. The protagonist justifies this with the belief that, “It was them or us.”

In the the novel, the catastrophe that wipes out most strains of cereal is caused by a mutated virus but, in the film adapted by inexperienced screenwriter Sean Forestal, chemical pollution is suggested as the reason. The film vaguely follows the plot of the novel, concentrating on a family led by the quick-thinking father who has foreseen such a disaster. The family journeys across an England that has collapsed into anarchy and mob-rule, until they reach sanctuary at the potato farm. With the suggestion that the fall of civilisation tends to bring out the worst in people and that such qualities as compassion had better be put in mothballs until more comfortable times return, the film is very similar to Panic In The Year Zero (1962) produced eight years earlier by another character actor dabbling in directing: Ray Milland.

In the the novel, the catastrophe that wipes out most strains of cereal is caused by a mutated virus but, in the film adapted by inexperienced screenwriter Sean Forestal, chemical pollution is suggested as the reason. The film vaguely follows the plot of the novel, concentrating on a family led by the quick-thinking father who has foreseen such a disaster. The family journeys across an England that has collapsed into anarchy and mob-rule, until they reach sanctuary at the potato farm. With the suggestion that the fall of civilisation tends to bring out the worst in people and that such qualities as compassion had better be put in mothballs until more comfortable times return, the film is very similar to Panic In The Year Zero (1962) produced eight years earlier by another character actor dabbling in directing: Ray Milland.

However, No Blade Of Grass is rather crude and so disjointed it would give Quentin Tarantino‘s Pulp Fiction (1994) a run for its money. There are flashbacks, flash-forwards, interior dialogue heard over exterior long-shots, and so much stock footage of pollution, you’ll think you’re watching Koyaanisquatsi (1982) on fast-forward. The mood changes violently from one scene to the next, the visual quality and colour flash from shot to shot as though it had been photographed by different crews, and the actors seem to be unsure of what kind of film they are supposed to be making.

However, No Blade Of Grass is rather crude and so disjointed it would give Quentin Tarantino‘s Pulp Fiction (1994) a run for its money. There are flashbacks, flash-forwards, interior dialogue heard over exterior long-shots, and so much stock footage of pollution, you’ll think you’re watching Koyaanisquatsi (1982) on fast-forward. The mood changes violently from one scene to the next, the visual quality and colour flash from shot to shot as though it had been photographed by different crews, and the actors seem to be unsure of what kind of film they are supposed to be making.

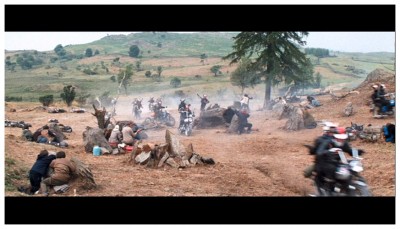

Some of the blame for the film’s lack of cohesion rests with distributor Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a number of sequences were cut by them at the last minute. That being said, there are some memorable sequences, such as the attack on some straggling refugees by a horde of armed motorcycle huns wearing horned helmets, and the scenes early in the film when quantities of rich food are consumed by well-fed patrons in a restaurant, all of whom are oblivious to the pictures of Third World misery being shown on a television screen above them.

Some of the blame for the film’s lack of cohesion rests with distributor Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a number of sequences were cut by them at the last minute. That being said, there are some memorable sequences, such as the attack on some straggling refugees by a horde of armed motorcycle huns wearing horned helmets, and the scenes early in the film when quantities of rich food are consumed by well-fed patrons in a restaurant, all of whom are oblivious to the pictures of Third World misery being shown on a television screen above them.

Just like Soylent Green (1973) and other ecological-friendly films, No Blade Of Grass opens with a montage of polluted scenes: Factories spewing smoke; dead birds; arid land; traffic jams; and armed masses of people while Roger Whittaker sings Gone With The Dawn. An image of Earth from space zooms into a crowded football stadium as a voiceover explains that the environment has been destroyed. More scenes of dilapidated cars, factory smoke, car exhaust, and crowded city streets lining a smog-filled city of high rise apartments and human masses prove the narrator’s claim. And these shots are reinforced by another montage of industrial waste water, toxic smoke emissions, pesticides, strip mining, oil spills and red tides killing water birds, starving children, thousands of cars in an airport parking lot, and a nuclear explosion.

Just like Soylent Green (1973) and other ecological-friendly films, No Blade Of Grass opens with a montage of polluted scenes: Factories spewing smoke; dead birds; arid land; traffic jams; and armed masses of people while Roger Whittaker sings Gone With The Dawn. An image of Earth from space zooms into a crowded football stadium as a voiceover explains that the environment has been destroyed. More scenes of dilapidated cars, factory smoke, car exhaust, and crowded city streets lining a smog-filled city of high rise apartments and human masses prove the narrator’s claim. And these shots are reinforced by another montage of industrial waste water, toxic smoke emissions, pesticides, strip mining, oil spills and red tides killing water birds, starving children, thousands of cars in an airport parking lot, and a nuclear explosion.

We are told, “It is the end of life,” and after focusing on the explosion, the camera pans back up into space while the narrator calmly states, “And then one day, the polluted Earth could take no more.” It’s obvious that Cornel Wilde’s heart was in the right place – unfortunately his cameras were not. And it’s with that thought in mind I’ll now bid you goodnight and farewell until we meet again to grope blindly around the bear-trap known as Hollywood for next week’s star-spangled celluloid stinker for…Horror News. Toodles!

We are told, “It is the end of life,” and after focusing on the explosion, the camera pans back up into space while the narrator calmly states, “And then one day, the polluted Earth could take no more.” It’s obvious that Cornel Wilde’s heart was in the right place – unfortunately his cameras were not. And it’s with that thought in mind I’ll now bid you goodnight and farewell until we meet again to grope blindly around the bear-trap known as Hollywood for next week’s star-spangled celluloid stinker for…Horror News. Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

I’m watching it right now and about the middle of it what was Cornel Wilde thinking? This thing is like a huge slog I feel like I’m slogging along with the characters very heavy-handed opening of showing pollution all over the world blah blah blah I’m going to force myself to finish it but I’m not looking forward to it so much for that

Thanks for reading! Yes, it’s a mess: Over the top sensationalistic details of exploitative situations (so-called 70s reality); clumsy editing complete with ridiculous flash forwards; everyday family folk who simply walk away after committing crimes they would never have contemplated just a few days before; overuse of typical 70s lab effects in an attempt to gloss up weak images; bland el-cheapo music score (except for a main title song nicely performed by Roger Whittaker). It all adds up to a messed-up message film in the worst of 70s style. In many ways it’s worse than some of the low budget 50s films it emulates.