SYNOPSIS:

“A virulent new disease is killing the children of Manhattan and has reached epidemic proportions. Peter Mann in desperation asks the entomologist, Doctor Susan Tyler, if she can help by killing the disease carrier, the common cockroach. Susan genetically engineers a new species of predatory insect to exterminate the cockroach and then die off. This novel solution works and the children recover but nature isn’t the laboratory and things don’t exactly go according to plan. Three years later people start to disappear, mutilated bodies are found and wild rumours of giant insects mimicking man start to emerge from the bag people living in the subway under Manhattan. Peter and Susan are called in to investigate.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Guillermo del Toro was born in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, raised in a strict Catholic household, and studied at the Centro de Investigación y Estudios Cinematográficos. He started making short films at the age of eight, experimenting with father’s Super-8 camera, and eventually wrote four and directed five episodes of the cult anthology television show La Hora Marcada. He studied special effects and makeup with maestro Dick Smith, and spent the following decade as an effects designer, forming his own company, Necropia. His first feature film, Cronos (1993) starring Federico Luppi and Ron Perlman, made a big splash and was selected as the Mexican entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 66th Academy Awards. Then, at the age of 33, del Toro was given a US$30 million budget from Miramax to shoot his second feature: Mimic (1997).

The three-page story Mimic by Donald Wollheim was first published in Fantastic Novels magazine in 1950, and was adapted by del Toro intended to be one segment of a movie called Light Years, accompanied by other segments by Danny Boyle and Bryan Singer. However, Dimension Films producer Bob Weinstein was so excited by del Toro’s pitch for a scene in which Mira Sorvino was to be dragged away by a giant cockroach, that he asked the director to develop the idea into a full-length screenplay. Although daunted by the idea of making a believable giant bug movie in the nineties, he was also excited by the challenge. Following up a debut feature as assured and perversely stylish as Cronos was always going to be a tough one for del Toro, whose control over every element of that refreshingly original vampire movie helped create a deeply personal and original work.

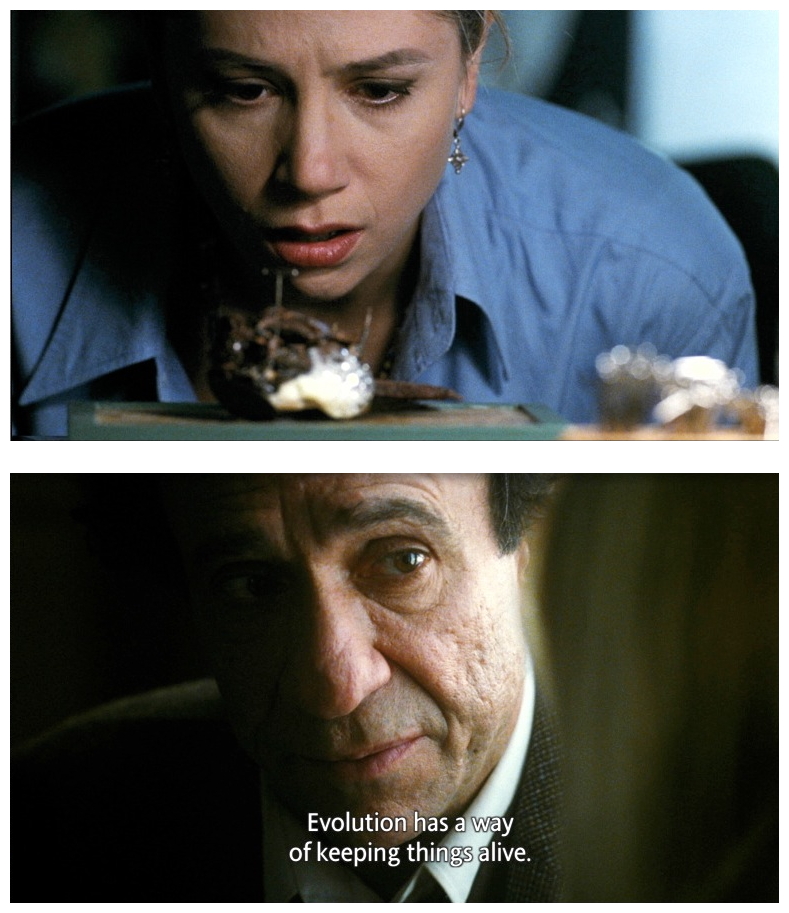

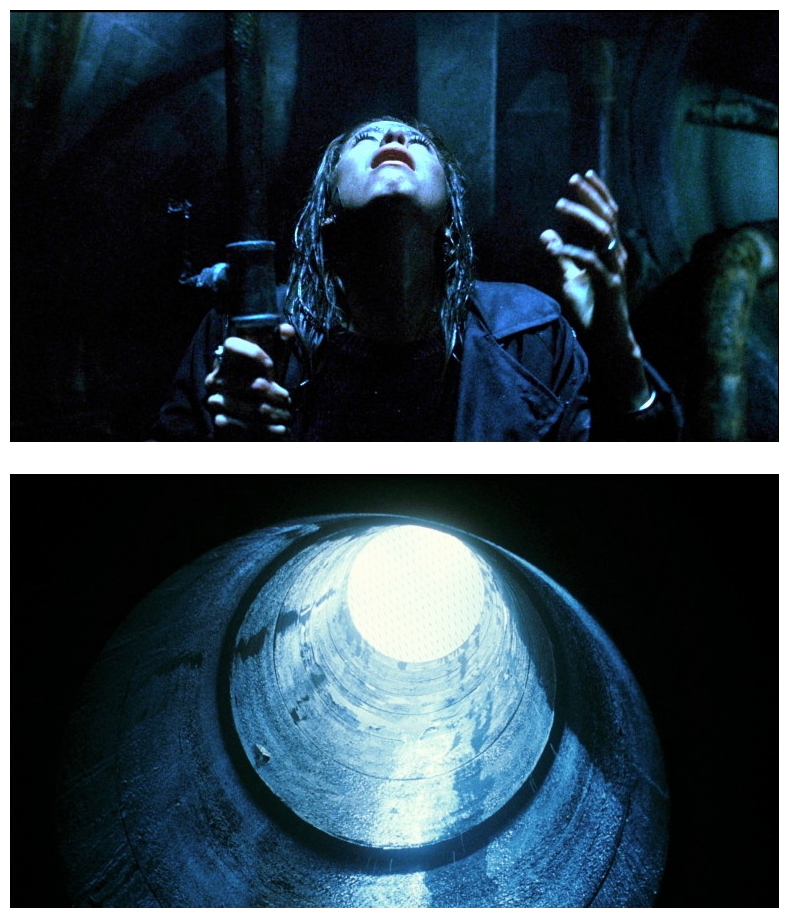

“The moment I thought, this is impossible, it’s suicidal, it became as perversely appealing to me as showing a sixty-year-old man licking blood off a bathroom floor, so I said to myself, I’m going to make it deadly serious.” Over the next year he collaborated with Matthew Robbins, Matthew Greenberg and ex-Roger Corman acolyte-turned-independent-filmmaker John Sayles, who had written two classic low-budget mutation movies, Piranha (1978) and Alligator (1980). Sayles introduced the idea of genetic manipulation, together with the concept of the Judas Breed, a specifically created strain of cockroach designed to breed with, and bring about the extinction of, the disease-carrying insect hosts. During this lengthy period of pre-production, del Toro also worked closely with Rick Lazzarini, whose original creature designs were later fleshed out by Tyruben Ellingson and Rob Bottin. The result was a species of sleek, beautiful bugs that could pass in the dark tunnels of the New York subway for grubby homeless humans, the long wing casings resembling a shapeless overcoat, and the complex folding mandibles, a human face.

“I said to Ty, let’s not make a monster, let’s make a creature. Our watchword was they were all creatures of God, so we should make them as beautiful and entomologically correct as nature would have made them. The insects in most giant bug movies look like fuzzy Volkswagens with big chomping mandibles, they never look real. We used dozens of books on ants, termites, praying mantises and cockroaches to research the design of the creatures – in terms of movement, texture, colour – so that they’d be absolutely organic and real.” Del Toro’s first American movie manifests tell-tale signs of an overlong gestation period and a difficult birth. That so much of del Toro’s original vision has survived intact through this torturous process is a testament to the depth of his imagination and determination (del Toro disowned the film after constant clashes with Bob Weinstein, who would frequently visit the set and make unreasonable demands about what should be shot, deviating away from the script. Since then del Toro has never worked with the Weinsteins).

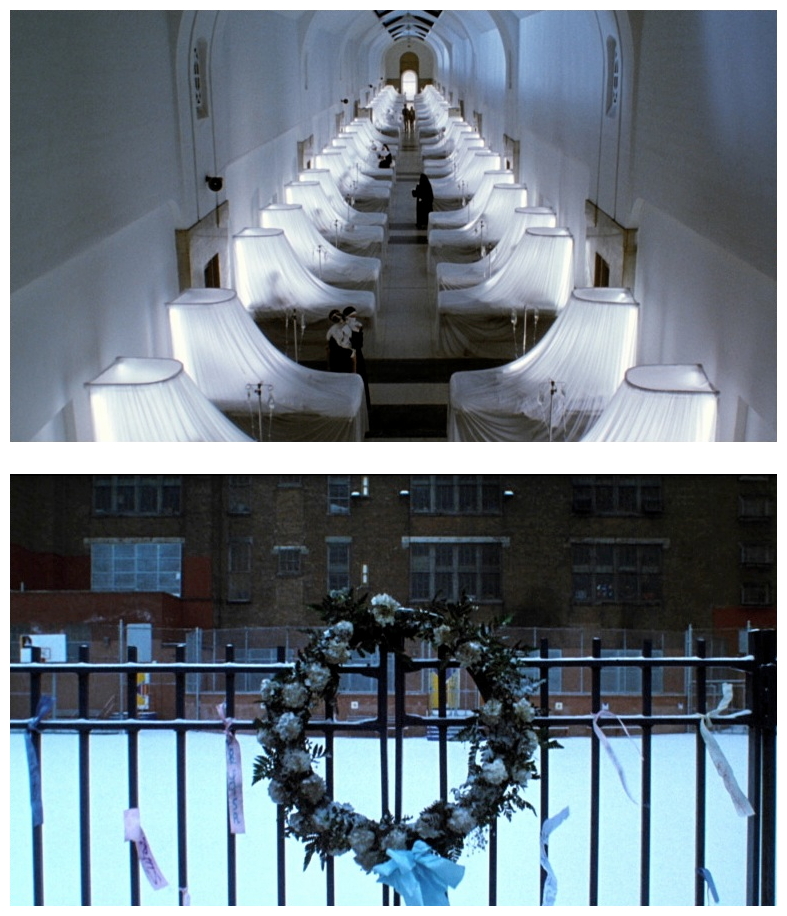

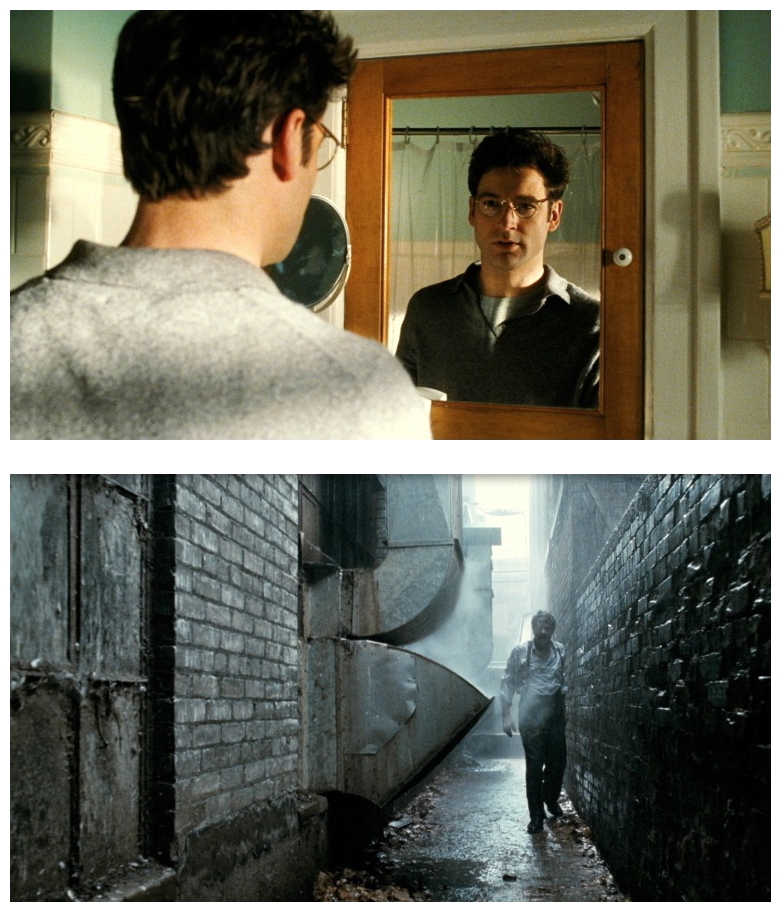

However, the many mutations that the film underwent during the scripting process, shooting schedule and final editing have resulted in some rather uneven pacing, occasional lapses of storytelling clarity, and a curiously hybrid feel to the movie as a whole. Juxtaposing images of poetic beauty with scenes of stark terror, del Toro doesn’t always manage to dovetail the serious underlying allegory about the perils of genetic manipulation with the relentless kinetic scenes of subterranean terror. When a polio-like epidemic threatens the lives of all the children of New York, entomologist Doctor Susan Tyler (Mira Sorvino) and her husband, disease control expert Peter Mann (Jeremy Northam) create a genetically altered Judas Breed that will mate with and destroy the disease’s main carrier, the humble but much-loathed cockroach.

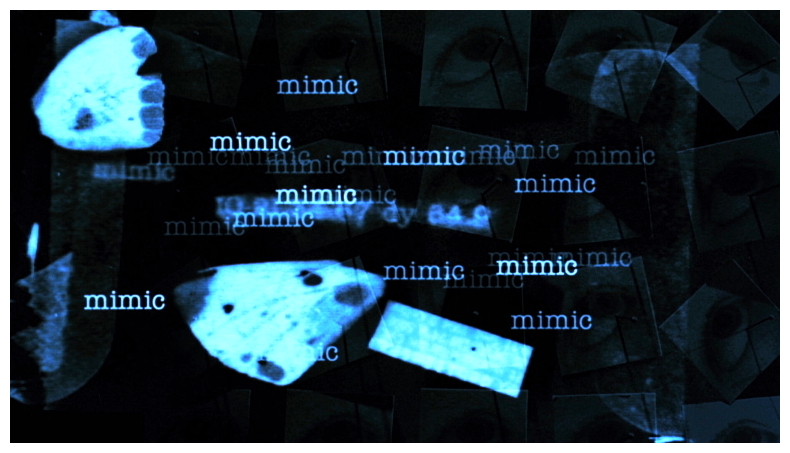

But the cocky scientists have underestimated the insects’ capacity for mutation and survival and, a few years later, a race of giant bugs that mimic homeless humans are breeding in the tunnels beneath New York. Plunged into the bugs’ subterranean habitat, Tyler and Mann are stalked by their own bastard creation. Also wandering the tunnels are other potential foodstuffs – Mann’s assistant Josh (Josh Brolin), transit cop Leonard (Charles S. Dutton) and an old shoe repairman Manny (Giancarlo Giannini) who is looking for his lost autistic son Chuy (Alexander Goodwin). To avoid the razor-sharp legs and bone-crushing mandibles of the voracious giant bugs, the human prey are forced in turn to mimic their insect predators, hiding and scuttling about in the dark in order to survive. Surprisingly serious and grim, but with a little of del Toro’s surreal humour thrown in for good measure, Mimic‘s consistent atmosphere of dread is sustained from the scene-setting title sequence by Kyle Cooper (responsible for literally hundreds of film and TV credit sequences), right through to the terrifying finale in which the humans are trapped inside a cramped subway carriage by their ferocious insect adversaries.

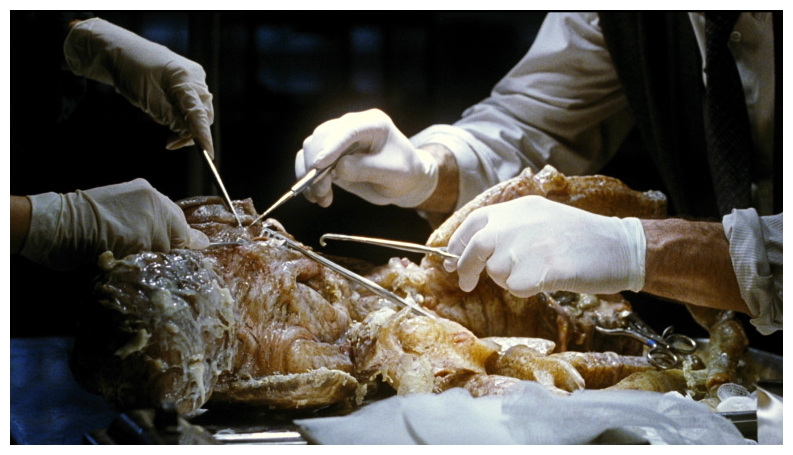

The casting of Mira Sorvino as Doctor Tyler introduced an essential dramatic seriousness, although del Toro’s desire to work with her stemmed as much from her smaller supporting roles in Barry Levinson‘s Quiz Show (1994) and Ted Demme‘s Beautiful Girls (1996) as from her Oscar-winning performance as the helium-voiced hooker in Woody Allen‘s Mighty Aphrodite (1995). Naturally, given Sorvino had won an Academy Award for this last role, the director treated her with all due respect – by terrorising her from morning to night, forcing her to flee from giant insects, and smearing her with revolting internal fluids. “It was a very taxing role for Mira. The sort of method acting that Mira does has to do with internalising of feelings. Often, she arrived on the set looking absolutely devastated, because of the terrible nightmares she’d been having in which I would extract fluids from her internal glands and say, now we have to rub this all over you.”

“Filming the scenes in which Mira and the others are trapped inside the subway car by the giant bugs were particularly tough. They had to spend thirteen consecutive days inside a normal subway train carriage. Originally we’d designed it to have ‘wild walls’ so we could take them away and get the camera or crane apparatus inside. But because we needed to rig the car to rattle around like a martini shaker, the outside had to be completely wrapped in aeroplane wire. We couldn’t open it up at all, and we had to use hand-held cameras or a Steadicam the whole time. It was like filming Das Boot (1981) in a much smaller space. I called this style of the filming ‘third person camera’ because the camera becomes like another actor. It’s something I noticed in some of Hitchcock’s more melodramatic movies, like Notorious (1946), The Birds (1963) and, of course, Vertigo (1958).”

“It’s where the camera glides rather slowly and very smoothly into position, for shots in which it almost seems like an interested bystander, like a guy who’s really gawking at the action, saying, ‘Let me see that. Oh, that’s interesting’. The camera is always coming from behind something, or gliding towards or away from the action. For example, when Mira Sorvino is on the platform alone, being stalked by the bug, the camera sorts of peeks at her from behind the columns. It’s a very playful and sensual style of storytelling, which is also very involving for the audience. That’s when the whole thing clicked for me, on a metaphorical, religious level – that idea of a world abandoned by God, where there is only the final battle, a test of wills if you like, between Man and Insect.”

“There’s a definite evolution to their characters, from the arrogant scientists we see at the beginning to the point where they are trapped in a subway car by the giant bugs. By the time they reach that point, it doesn’t matter whether they’re a brilliant scientist, a transit cop or a shoeshine man. It doesn’t matter whether you’re black, white, old, young, male or female. To the bugs they’re just food.” Despite some structural weakness, this demands to be seen on the big screen, if only to appreciate the terrible beauty of the creature designs, the lustrous light and shadow of Dan Lausten‘s cinematography, and the lush, unashamedly melodramatic strains of Marco Beltrami‘s score. Deliberately breaking the unwritten Hollywood rule which says that animals, old people and children always survive the last reel, del Toro also keeps us guessing right to the end about who will die and who will not. And it’s with this thought in mind I’ll ask you to please join me again next week to have your innocence violated beyond description while I force you to submit to the frightening terrors of…Horror News! Toodles!

Mimic (1997)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews