SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

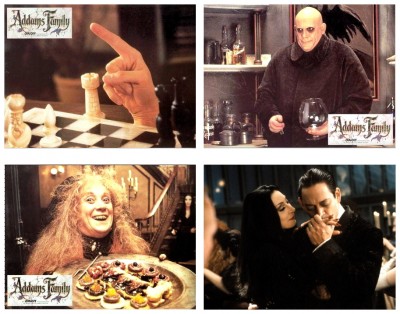

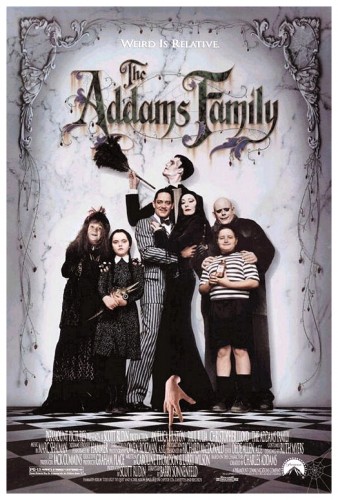

“The Addams step out of Charles Addams’ cartoons. They live with all of the trappings of the macabre (including a detached hand for a servant) and are quite wealthy. For twenty-five years uncle Fester has been missing. An evil doctor finds out and introduces a fake Fester in an attempt to get the Addams family money. Added to this mix is a crooked accountant and his loan shark and a plot to slip in the shark’s son into the family as their long lost Uncle Fester. The youngest daughter has some doubts as to the sincerity of the new uncle Fester. The fake uncle adapts very well to the strange family. Can the false Fester find his way into the vault before he is discovered? Can the doctor carry out her evil plans and take over the Addams family fortune?” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Charles Addams was a New Yorker magazine cartoonist famous for his darkly humorous and macabre characters known collectively as the Addams Family, which became the basis for two live-action television series, two animated television series, three motion pictures and a Broadway musical. Since the original cartoons were simple one-panel illustrations, much of the family’s development and history (as we know it today) grew out of the 1966 television series starring John Astin and Carolyn Jones. The tone of the series was set by producer Nat Perrin – writer of several Marx Brothers movies – who created story ideas, rewrote every single script and even directed an episode. Much of the dialogue is his and, as a result, the character of Gomez Addams is often compared to Groucho Marx. The series often employed the same type of satire and screwball humour as the Marx Brothers, lampooning politics, the legal system, Beatlemania, and Hollywood.

Considering the proliferation of Hollywood films based on vintage television properties during the late eighties, it was no surprise to learn that Orion Pictures had started production on a film version. Unfortunately, Orion’s financial troubles began around the same time, ultimately leading to the studio’s demise, so Paramount Pictures purchased the film rights and eventually completed The Addams Family (1991), but only after re-arranging a lot of deck-chairs: Cher was originally cast as Morticia until Anjelica Huston became available; Sir Anthony Hopkins turned down the role of Uncle Fester, substituted at the last minute by Christopher Lloyd; Tim Burton was originally set to direct (he had worked previously with writers Caroline Thompson and Larry Wilson) but was replaced by first-time director Barry Sonnenfeld; cinematographer Owen Roizman quit after only a month; and his replacement (Gale Tattersall) had to quit due to a severe sinus infection, forcing Barry to do the cinematography himself.

Working as a cinematographer for the award-winning Coen Brothers, Barry had to film such things as the mysterious flying hat in Miller’s Crossing (1990), or develop a ‘baby-cam’ to record the infant’s-eye-view scuttlings of quintuplets in Raising Arizona (1987) and, in Rob Reiner’s Misery (1990), he used the camera to emphasise the enormity of James Caan’s imprisonment by Kathy Bates. Barry felt he was well-prepared to take the helm of the morbidly funny Addams Family for his directing debut. Unfortunately, one of the first things the director did on-set was to faint, an act that didn’t inspire much confidence in his cast nor crew. “All the great directors faint at some point in their careers,” he insisted. According to Barry, the transition from cameraman to director was not that difficult, especially since The Addams Family is a very visual movie, full of atmosphere and sight gags. I had the opportunity to chat with Barry on the set of The Tick live-action television show back in 2001, and asked him what was it really like to be a movie director:

“Having to make hundreds of decisions a day that ultimately don’t matter, but add up to mattering a lot. ‘Yes, let’s have six of those book covers’ and ‘No, we won’t see their backs’ and ‘No, it should be green and not red’. You answer millions of questions like these every day, and the answers are very important to the people asking them. Each question carries equal weight. ‘Should he park the car here, or there?’ Oftentimes it doesn’t matter what you say as long as you give an answer. Actors always feel the film is about their character, as they should. When you watch dailies, the assistant cameraman thinks the entire movie is about focus, and the soundman think it’s about that noise. A director’s job is to keep the balance and answer all the questions with authority. I’ve been lucky, in that I’ve been immature and wacky enough as a person and director that everyone wants to help me.”

Barry also directed the sequel, Addams Family Values (1993), which was deemed a box-office failure, but he received critical acclaim for Get Shorty (1995) based on the novel by Elmore Leonard and starring John Travolta as stand-over film producer Chili Palmer. Another stand-over film producer by the name of Steven Spielberg asked Barry to direct Men In Black (1997), which had its fair share of problems before finally seeing the light of day as the surprise blockbuster of the year. After Clint Eastwood turned down the role of Agent Kay, Tommy Lee Jones agreed to participate only if the script was rewritten to reflect the original comic. Co-star Will Smith wasn’t approached until Chris O’Donnell and David Schwimmer had passed, and even director Barry didn’t come on board until several others (including Quentin Tarantino) had rejected the project. With last-minute replacements, on-set quarrels and extensive re-shoots, it was a miracle that the final product was so well received.

In an attempt to make lightning strike twice, producer Jon Peters asked Barry to direct Wild Wild West (1999) which was widely regarded as an expensive disappointment. In a practice that has become all-too-common in Hollywood today, Peters took an excellent original script (in which H.G. Wells, Jules Verne and Mark Twain are forced to design war machines by a vengeful Southern General), and simply slapped an old television title on it. I Spy (2002) is another example of this disturbing practice…but I digress. Barry Sonnenfeld may never leave his cinematographer’s roots behind – when he reminisces about his directorial debut, he singles out visuals, like the point-of-view shot of a juggled knife going right down Christopher Lloyd’s throat. But he thinks the bigger issue in The Addams Family – about a clan whose values are at odds with the wholesome world around them – is about how nonconformity is good, and that’s the outlook he intends to keep as he continues to make movies. On this rather upbeat note I’ll quickly thank the Washington Post and Video Magazine for assisting my research for this article, and ask you to please join me next week when I have another opportunity to make your stomach turn and your flesh crawl with another lusting, slashing, ripping flesh-hungry, blood-mad massacre from the back side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews