SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

“In London, a serial-killer is raping women and then strangling them with a neck tie. When the reckless and low-class with bad temper bartender Richard Blaney is fired from the pub Global Public House by the manager Felix Forsythe, he decides to visit his ex-wife Brenda, who owns a successful marriage agency. Her secretary Miss Barling overhears an argument of the couple, and Brenda invites Richard to have dinner with her in a fancy restaurant. Then she put some money in his overcoat and does not tell him to avoid his embarrassment with the situation. Meanwhile Richard’s friend Bob Rusk visits Brenda in her office, rapes her and kills her with his neck tie. When Richard finds the money in his pocket, he visits Brenda but finds the agency closed, then he goes with his girlfriend Babs Milligan to an expensive hotel. Miss Barling sees Richard leaving the building and finds her boss strangled; she calls the New Scotland Yard and Richard becomes the prime suspect. When Bob kills Babs, he frames Richard that is arrested and sentenced to life. But the Chief Inspector Oxford that was in charge of the investigation is not absolutely sure that Richard is the serial-killer.”

REVIEW:

Alfred Hitchcock began his film career in 1920 as a designer of silent film title cards, soon becoming art director, scriptwriter, and director. After nine silent films including The Lodger (1927) and The Ring (1927), he directed the first British sound film, Blackmail (1929), followed by a number of superb thrillers: The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The Thirty-Nine Steps (1934), Young Innocent (1937) and The Lady Vanishes (1938). He was then invited to America by producer David O. Selznick to make Rebecca (1940) and stayed In the USA for most of his life. Hitchcock became the complete filmmaker, an auteur to whom no aspect of the filmic structure is a mystery. Every image that appears on screen has been calculated precisely, from the screenplay and photographic composition to the editing and soundtrack. Even the marketing of the finished product was a major part of Hitchcock’s concern, and the gleam in his eye is that of a born showman. His name is known to almost every person who has ever entered a cinema and his personality is more familiar to us than those of his many major stars.

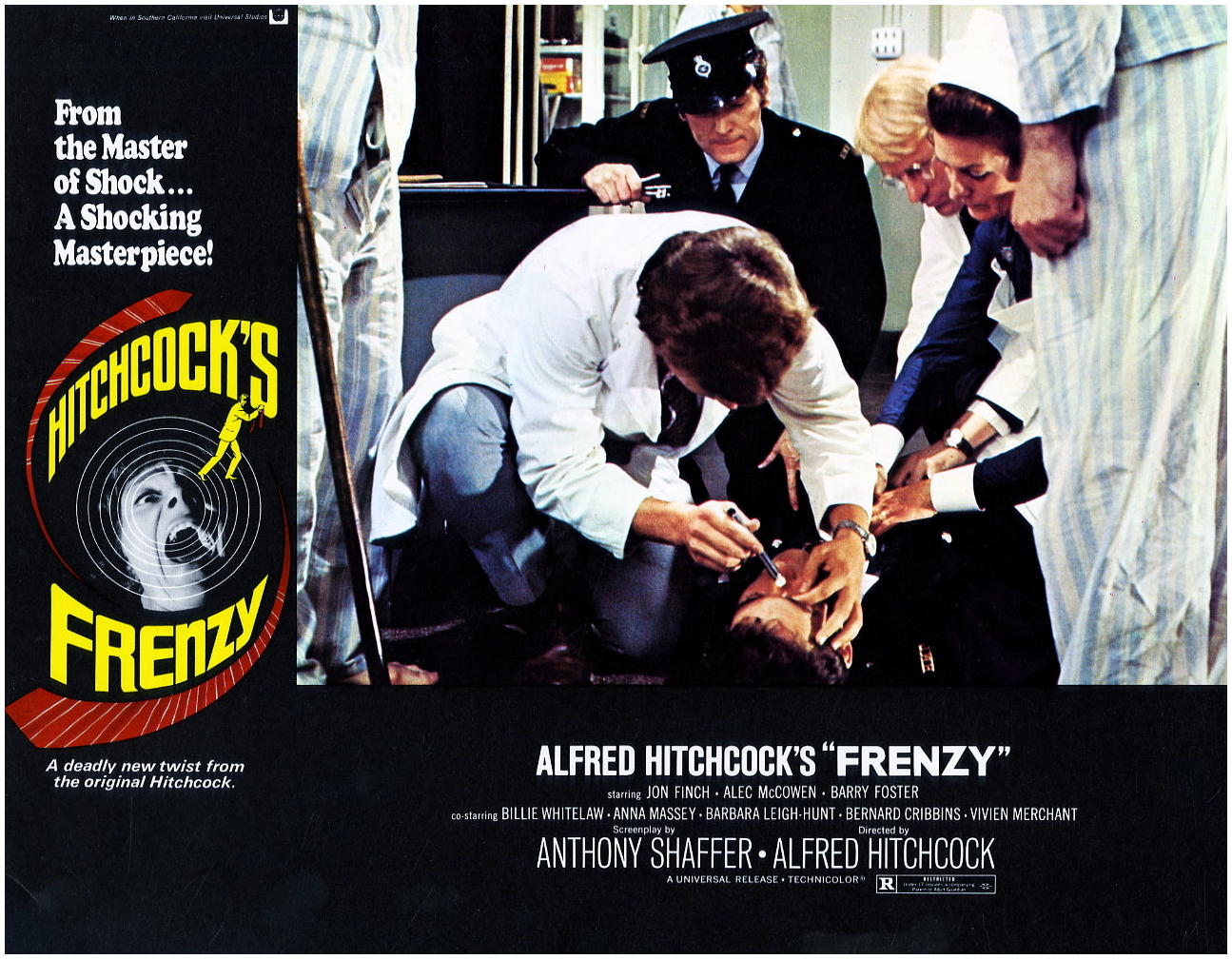

After his seventieth birthday, Hitchcock decided to return to England to make a murder mystery with all the trappings of his past career embedded in it. Frenzy (1972) in some respects harked back even beyond his Gaumont-British period, being in certain aspects reminiscent of The Lodger in its treatment. The shock opening, for instance, in which the disquiet felt by the female population of London at the presence of an unknown strangler of blondes at large is dramatised by the appearance of a floating nude body during a riverside ceremony in front of County Hall, is similar to the opening of the 1927 film. Hitchcock originally planned to do his cameo as the body floating in the river, in fact a dummy was even constructed to do the shot. Plans were changed and a female body was used instead, and Hitchcock became one of the members of the crowd on the riverbank.

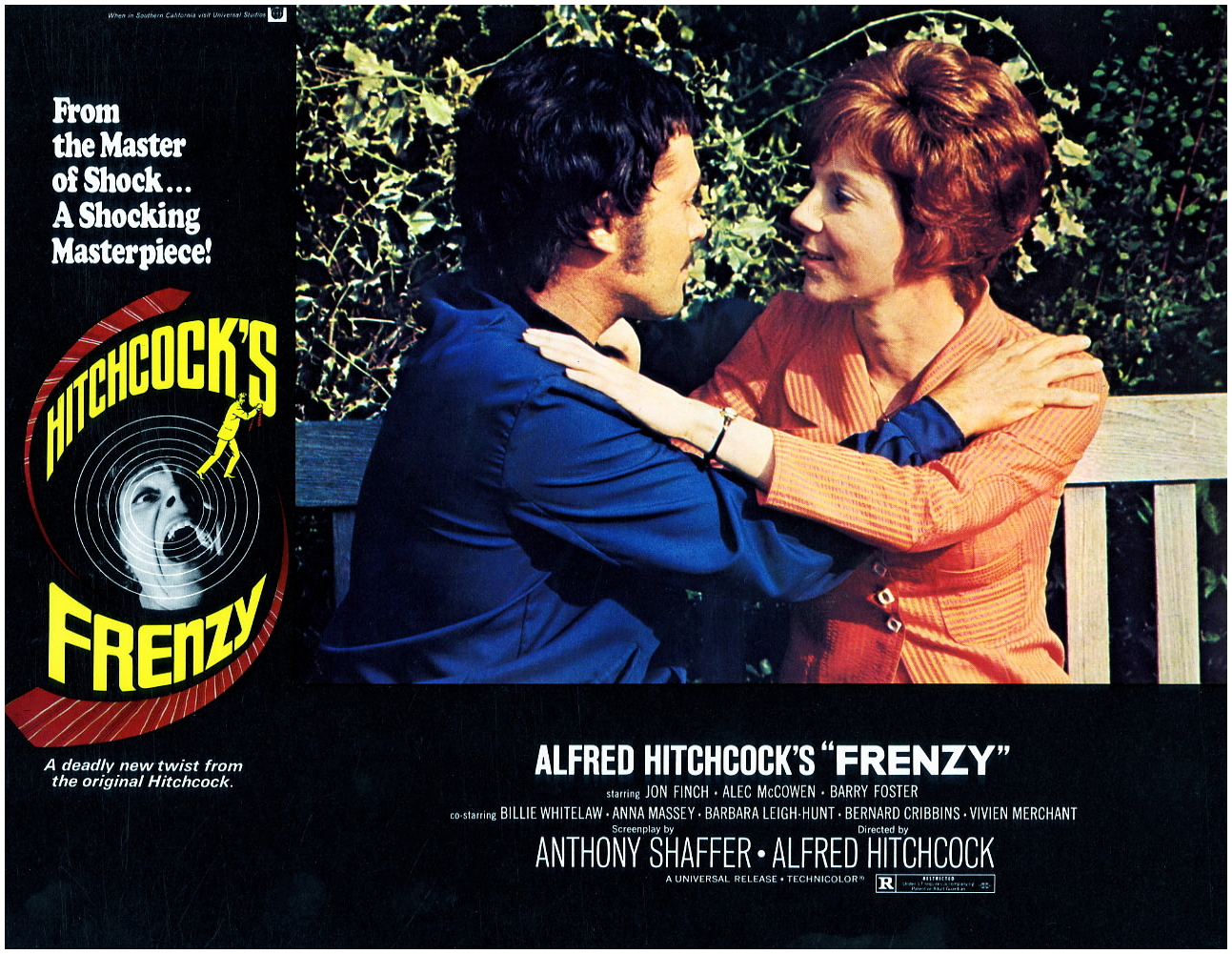

Unfortunately, Hitchcock made a couple of errors in Frenzy, the kind of errors that had got him into trouble in previous films. The first was to make his hero, played by Jon Finch, not only unlikable but downright spurious. He boasts, for instance, about his wartime RAF record, although the film is clearly set in London in the seventies, which would have meant he was a squadron leader before the age of ten. The second mistake was to reveal the identity of the killer too soon, thus removing much of the suspense of the story and, since Jon Finch plays an unsympathetic character with disturbing ambiguities, it might have been better to have taken the audience further down the garden path. The killer, played by Barry Foster, is a thoroughly unpleasant psychotic homosexual which to some extent forces sympathy against him, but the best performances are the supporting ones: Alec McCowan as a patient police detective saddled with a socially-conscious gourmet wife (Vivien Merchant) who is constantly serving him with unpalatable snob food, and Anna Massey as the most appealing of the victims.

The cinematography in Frenzy is undoubtedly Hitchcock. Midway through the film there is a continuous shot in which the camera backs away from the door of an upstairs apartment and descends the staircase, seemingly uncut, to the ground level, out the building’s front door, then to the opposite side of the street. The interiors were shot with an overhead track in a studio, and there’s a subtle cut as a man passes by the front door, carrying a sack of potatoes. This is subtly blended into a new shot of the camera pulling away from the building exterior that was actually used on location.

There is also a certain amount of black comedy, for instance the hiding of a body in a potato sack on the back of a loaded truck, with a bare foot constantly exposing itself. Despite the nudity and frank dialogue, Frenzy is a very old-fashioned film, and Anthony Shaffer’s screenplay is over-literate and unconvincing. So much so that several of the cast were unhappy with the lack of authenticity and Britishness of some of the dialogue. Jon Finch would send notes to Hitchcock suggesting improvements, which did not please him one bit: “Jon, I said you could make alterations, I didn’t say you could rewrite the whole script!” Nevertheless many of Finch’s amendments were indeed used.

The use of London locations is effective, particularly Covent Garden during its last days as a fruit market, and there are many signs of the old Hitchcock, as imaginative and inventive as ever, even if the overall effort falls way short of his best. It was his 52nd film in fifty years, a creditable score in a long life of film-making, and by no means the end. He was already planning his next (and final) project, Family Plot (1976), based on the novel by Victor Canning and adapted by Ernest Lehman, who wrote North By Northwest (1959).

Hitchcock always considered himself primarily as a storyteller with film, an entertainer and a showman. He deliberately restricted himself in his choice of subject matter, avoiding epics, westerns, musicals and historical biographies, preferring close-ups of the human predicament which, in his terms, comes down to menace from dark hidden powers, be they the psychosis of a murderer or the paranoia lurking within apparently normal people. When he has strayed from his narrowly defined territory the result has been failure, whether it be the ponderous inappropriateness of Waltzes From Vienna (1934) or the dreary improbability of Jamaica Inn (1939).

There is a studied care and precision in his craft which have invariably given his films a distinctive polish. His pre-production capacity is legendary: Before a single frame of film is exposed, he would read the script repeatedly, rejecting and rewriting, he would never improvise on-set, his actors rehearsed their roles to perfection, his cinematographer knew exactly what was required, he had no need to look through the viewfinder. When asked about his film-making methods, he would simply state, “My films are made on paper.” With that thought in mind I’ll thank you for reading, and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to simultaneously raise both hackles and cackles with more dreadful dross from the drains of Los Angeles in another trouser-moistening fear-filled film review for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

ONE OF HITCHCOCKS BEST SEE IT