SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

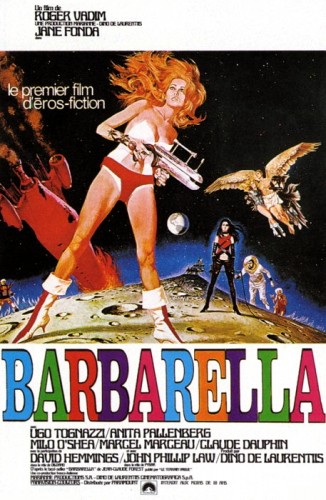

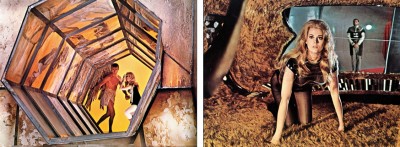

“After an in-flight anti-gravity striptease (masked by the film’s opening titles), Barbarella, a 41st century astronaut, lands on the planet Lythion and sets out to find the evil Durand Durand in the city of Sogo, where a new sin is invented every hour. There, she encounters such objects as the Excessive Machine, a genuine sex organ on which an accomplished artist of the keyboard, in this case, Durand Durand himself, can drive a victim to death by pleasure, a lesbian queen who, in her dream chamber, can make her fantasies take form, and a group of ladies smoking a giant hookah which, via a poor victim struggling in its glass globe, dispenses Essence of Man. You can’t help but be impressed by the special effects crew and the various ways that were found to tear off what few clothes our heroine seemed to possess. Based on the popular French comic strip.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

For most of the sixties, genre cinema had been going through a very quiet period and, incidentally, not making much money for the film studios. Of the few real commercial successes in the genre between 1960 and 1967, most were fringe fantasy: Doctor No (1962), The Birds (1963), Doctor Strangelove (1963), Mary Poppins (1964) and You Only Live Twice (1967). Apart from Mary Poppins’ ability to levitate, there was not much in the way of hardcore supernatural or science fiction in any of these. Curiously enough, the first signs of a renewed interest in fantasy films came from the French rather than Hollywood. One French film of 1968 was a major popular success, and did much to resuscitate science fiction in the minds of commercial movie-makers. This was Roger Vadim‘s Barbarella (1968), starring the director’s then-wife Jane Fonda.

A lot of people dismissed Barbarella as nothing more than an over-prolonged sex joke. Certainly the dopey and sexually ignorant role played with naive panache by Fonda was the not-very-subtle core of the film. Barbarella is a kind of innocent ‘Candide’ figure, much coupled with, moving through the corrupt world of a wicked planet and its capitol city of Sogo, after being instructed by the World President to rescue a missing scientist. Puritanical critics resented the blatant sexism of the film and its aimless episodic plot (based on the comic strip by Jean-Claude Forest) was seen as betraying the intellectual capabilities of science fiction.

A lot of people dismissed Barbarella as nothing more than an over-prolonged sex joke. Certainly the dopey and sexually ignorant role played with naive panache by Fonda was the not-very-subtle core of the film. Barbarella is a kind of innocent ‘Candide’ figure, much coupled with, moving through the corrupt world of a wicked planet and its capitol city of Sogo, after being instructed by the World President to rescue a missing scientist. Puritanical critics resented the blatant sexism of the film and its aimless episodic plot (based on the comic strip by Jean-Claude Forest) was seen as betraying the intellectual capabilities of science fiction.

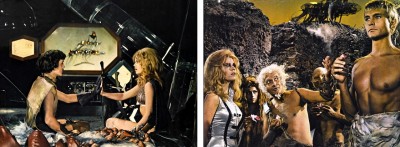

But the fact is, Barbarella succeeds in precisely the area that science fiction is supposed to excel – it creates a sense of wonder. The planet on which the story is set remains one of the most truly alien creations in cinema, with bizarre surprises around every corner: Small sinister children with razor-mouthed dolls, a blind angel, an ice yacht, rock people, weird spaceships, and the writhing monster Matmos over whom the city is built. All of this is genuinely exotic and a tribute to the production design of Mario Garbuglia and the wildly fantastic sets of art director Enrico Fea. Claude Renoir‘s light-filled photography is also excellent.

But the fact is, Barbarella succeeds in precisely the area that science fiction is supposed to excel – it creates a sense of wonder. The planet on which the story is set remains one of the most truly alien creations in cinema, with bizarre surprises around every corner: Small sinister children with razor-mouthed dolls, a blind angel, an ice yacht, rock people, weird spaceships, and the writhing monster Matmos over whom the city is built. All of this is genuinely exotic and a tribute to the production design of Mario Garbuglia and the wildly fantastic sets of art director Enrico Fea. Claude Renoir‘s light-filled photography is also excellent.

Despite the participation of Terry Southern, one of eight writers credited, some of the sex jokes are pretty dumb and school-boyish, but the scene featuring sexual intercourse using only the fingertips remains truly amusing, with David Hemmings as the young revolutionary. The last time I saw Mr. Hemmings was near the beginning of The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003) as Sean Connery’s stand-in.

Despite the participation of Terry Southern, one of eight writers credited, some of the sex jokes are pretty dumb and school-boyish, but the scene featuring sexual intercourse using only the fingertips remains truly amusing, with David Hemmings as the young revolutionary. The last time I saw Mr. Hemmings was near the beginning of The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003) as Sean Connery’s stand-in.

Barbarella was an early production by Italian entrepreneur Dino De Laurentiis, and the success of its bizarre settings and big-name actors probably served to warp his subsequent career by turning him away from the primacy of plot and character – witness the failure of Flash Gordon (1980) a decade later, which failed to reproduce the innocent lunacy of its comic strip origins. Contrary to popular myth, the films Dino produced are by no means always aesthetic disasters. Indeed, at the beginning of his career Dino De Laurentiis was a name to conjure with among intellectuals, for he produced Frederico Fellini’s early masterpieces La Strada (1954) and Nights Of Cabiria (1956), and would continue to finance ambitiously artistic films, such as Ingmar Bergman’s The Serpent’s Egg (1977).

Barbarella was an early production by Italian entrepreneur Dino De Laurentiis, and the success of its bizarre settings and big-name actors probably served to warp his subsequent career by turning him away from the primacy of plot and character – witness the failure of Flash Gordon (1980) a decade later, which failed to reproduce the innocent lunacy of its comic strip origins. Contrary to popular myth, the films Dino produced are by no means always aesthetic disasters. Indeed, at the beginning of his career Dino De Laurentiis was a name to conjure with among intellectuals, for he produced Frederico Fellini’s early masterpieces La Strada (1954) and Nights Of Cabiria (1956), and would continue to finance ambitiously artistic films, such as Ingmar Bergman’s The Serpent’s Egg (1977).

The execration of Dino by fans of genre cinema began with King Kong (1976), but he had been making fantasy films for a long time before that. Another example is Danger Diabolik (1968), directed by the unevenly brilliant Italian, Mario Bava. Like Barbarella, it was based on a European comic strip, starring John Phillip Law as a super-criminal who can scale walls with the agility of a monkey. The film is colourful and tongue-in-cheek. Diabolik makes love, for example, in a soft nest of bank notes. His apparent demise, after molten radioactive gold is poured over him, is followed by a close-up of the resulting statue’s eyes, one of which winks.

The execration of Dino by fans of genre cinema began with King Kong (1976), but he had been making fantasy films for a long time before that. Another example is Danger Diabolik (1968), directed by the unevenly brilliant Italian, Mario Bava. Like Barbarella, it was based on a European comic strip, starring John Phillip Law as a super-criminal who can scale walls with the agility of a monkey. The film is colourful and tongue-in-cheek. Diabolik makes love, for example, in a soft nest of bank notes. His apparent demise, after molten radioactive gold is poured over him, is followed by a close-up of the resulting statue’s eyes, one of which winks.

It may have been the commercial success of Barbarella and Danger Diabolik that set Dino on the wrong path, towards brightly-coloured comic strip action seasoned with parody, and the use of special effects that make remarkably little effort to look like anything realistic. It’s at this point I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I burst your blood vessels with another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

It may have been the commercial success of Barbarella and Danger Diabolik that set Dino on the wrong path, towards brightly-coloured comic strip action seasoned with parody, and the use of special effects that make remarkably little effort to look like anything realistic. It’s at this point I’ll ask you to please join me next week when I burst your blood vessels with another terror-filled excursion to the dark side of Hollywood for…Horror News! Toodles!

Barbarella (1968)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews