SYNOPSIS:

SYNOPSIS:

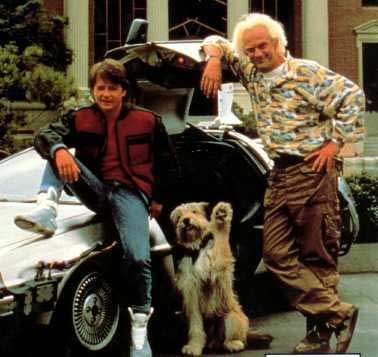

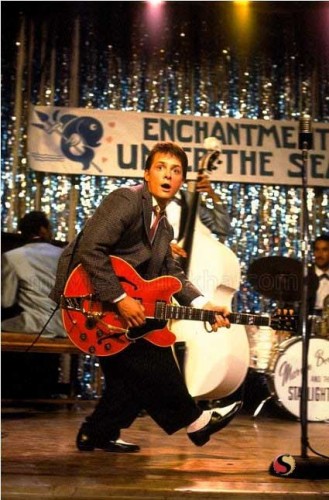

“Marty McFly, a typical American teenager of the Eighties, is accidentally sent back to 1955 in a plutonium-powered DeLorean time machine invented by slightly mad scientist. During his often hysterical, always amazing trip back in time, Marty must make certain his teenage parents-to-be meet and fall in love – so he can get back to the future.”

REVIEW:

In September of 1980, filmmakers Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale collaborated on a script whose ingenious time-travel theme extrapolated an idea by Gale: If I had gone to high school with my dad, would I be friends with him? Despite the high concept, Zemeckis and Gale found it a hard sell with the studios. In a current climate of teen sex comedies such as National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978) and Fast Times At Ridgemont High (1982), Back To The Future (1985) was a whimsical gamble that no-one was prepared to take. Enter Steven Spielberg and Universal Studios. Spielberg’s prior partnership with Zemeckis and Gale on I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978), 1941 (1979) and Used Cars (1981) led to his role as executive producer on Back To The Future, giving the project its green-light.

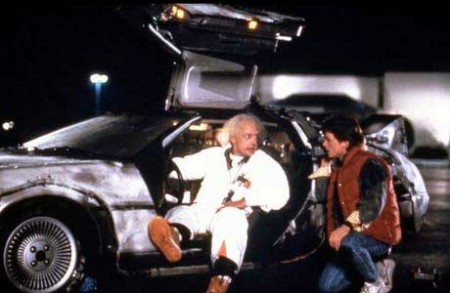

In casting the film, television star Michael J. Fox was always the first choice for Marty McFly. However, Fox’s commitments to the situation comedy Family Ties made his involvement unlikely. Alternative actors were narrowed down to two possible contenders. Both C. Thomas Howell and Eric Stoltz were screen-tested with the studio favouring Stoltz. But shortly after production commenced, Zemeckis was faced with the difficult task of replacing his lead actor, believing Stoltz’ performance to be at odds with the light-hearted tone of the film. Fortunately, Michael J. Fox agreed to juggle both the film and his television schedule, while Christopher Lloyd brought his eccentric flair to the role of Doc Brown in a madcap performance modeled on orchestral conductor Leopold Stokowski. The resulting chemistry between Fox and Lloyd would become a crucial ingredient in the film’s success.

In devising a method to travel through time, Zemeckis and Gale initially conceived a refrigerator before deciding on something a little more mobile, so three DeLorean automobiles were customised to include aircraft parts and other impressive-looking electronic extras. Equally important was sending Marty back in time instantaneously, retaining my old friend H.G. Wells’ principle of movement through time but not space, and limiting the need for expensive effects shots. Despite its roots in science fiction, Back To The Future contains a mere thirty-two visual effects shots, although the early script was in as much flux as the DeLorean’s capacitor, including a revised ending in which a nuclear explosion was used to propel Marty back to the future.

Location shooting in a real town was not an option and construction of the Hill Valley set on the Universal town square backlot allowed the Zemeckis to shoot the bright, idyllic fifties sequences before dirtying-down the set into an eighties version of the town. Budgeted at US$19 million, Back To The Future has grossed a whopping US$350 million worldwide and entered the annals of popular culture since its release in July 1985.

Location shooting in a real town was not an option and construction of the Hill Valley set on the Universal town square backlot allowed the Zemeckis to shoot the bright, idyllic fifties sequences before dirtying-down the set into an eighties version of the town. Budgeted at US$19 million, Back To The Future has grossed a whopping US$350 million worldwide and entered the annals of popular culture since its release in July 1985.

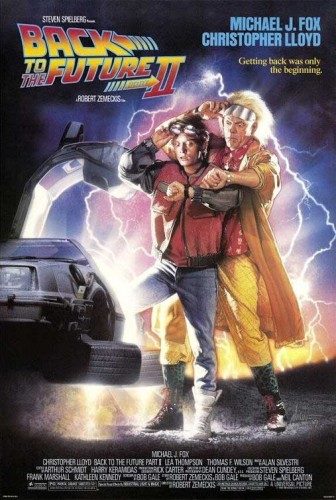

Given the phenomenal success of Back To The Future, a sequel was inevitable, however it would be almost five years before cast and crew would reunite for Back To The Future II (1989). Unlike the visionary George Lucas, Zemeckis and Gale had not conceived their time-travel enterprise as a franchise. The flying car at the end was intended as a gag only – Zemeckis and Gale never seriously considered a sequel, all they were worried about was breaking even at the box office. Naturally, the sequel depended on the involvement of Michael J. Fox, Christopher Lloyd and most of the original characters. Most agreed, but the outlandish demands made by Crispin Glover (who played George McFly) saw the character written out. However, footage from the first film featuring Glover was used without his permission resulting in the irate actor successfully suing. While Zemeckis was off shooting Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), Gale scripted a treatment that took Marty to 1967 in the third act, simply because he thought it would be cool to do the sixties. But after much soul-searching, Zemeckis and Gale seized a unique opportunity to go back to the events of the first movie with a different perspective.

Zemeckis said at the time it was the strangest movie he’d ever made, and was initially reluctant to take the film into the future to avoid the inevitability of wrongly predicting the future. However, when the future scenario proved essential to the narrative, Zemeckis and Gale decided a Utopian, tongue-in-cheek approach was necessary to differentiate their future from the more familiar (albeit Dystopian) predictions of George Orwell. Shot in the pre-digital era, part two’s elaborate effects sequences in which Michael J. Fox is required to play multiple interactive roles involved both time-consuming make-up demands on the actor and new shooting techniques including the use of a motion controlled Vista Glide camera allowing split-screen interaction between the characters. Budgeted at US$40 million, Back To The Future II opened November 1989 to mixed responses from critics and audiences thanks to a darker edge and cliffhanger ending, which meant fans had to wait six months for the thrilling conclusion.

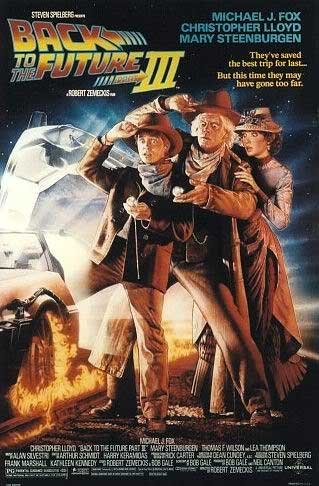

Shot back-to-back with part two over an eleven-month period, the third and final installment, Back To The Future III (1990) sent the intrepid time-traveling duo of Marty and Doc back to the wild west of 1885. Following the materialistic eighties of part one and the technology of part two, Zemeckis and Gale decided their concluding chapter should be a human journey with the western backdrop serving to accentuate the more simplistic fun-filled requirements of the tale. Thus the spotlight was turned on Doc, whose ambition to explore that other great mystery – women – leads to a sweet romance and Lloyd’s first on-screen kiss, with kindly schoolteacher Clara (Mary Steenburgen).

Moreover, with the Western in cinematic decline, the novelty of the shoot was met with passionate enthusiasm, particularly by Hollywood’s stuntmen elite and cinematographer Dean Cundey. Editing part two while shooting part three, the busy Zemeckis learned that sequels are tough, not least the baggage of opinionated expectation. Evoking the wit and charm of the original, Back To The Future III effectively concludes a trilogy of films that the modest Zemeckis and Gale insist are too recent to be considered classics, but they are also quick to admit that there’s something special about this story that touches everybody – it’s not restricted to just one generation or another. And it’s on that rather upbeat note I’ll bid you a good night and look forward to your company next week when I have the opportunity to raise the hackles on your goose-bumps with more ambient atmosphere so thick you could cut it with a chainsaw, in yet another pants-filling fright-night for…Horror News! Toodles!

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews