SYNOPSIS:

“Darkness has settled over New York City as Shredder and his evil Foot Clan have an iron grip on everything from the police to the politicians. The future is grim until four unlikely outcast brothers rise from the sewers and discover their destiny as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The Turtles must work with fearless reporter April O’Neil and her cameraman Vern Fenwick to save the city and unravel Shredder’s diabolical plan.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Superheroes often have a gut-wrenching backstory and lingering feelings of alienation amongst their senses or worldly injustice, and that’s fine – if Bruce Wayne’s parents hadn’t been murdered at all, he’d probably be visiting them in Florida every year where they’re happily cocktailing away their twilight years, and there would be no Batman. In films about tortured heroes like Bruce, the moments of humour and levity usually come via someone else, like the stupidity of the police sidekick Doyle in The Mask (1994) or the creepily amusing Joker in The Dark Knight (2008) or the apathetic prowess of Quicksilver in X-Men Days Of Future Past (2014). But what if, in addition to being crime-fighters, your heroes could also be totally radical party animals? That’s been the appeal of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles since their inception in 1983. Admittedly, two of them are more cerebral (“Leonardo leads, Donatello does machines…”) but the other two are introduced to us with real attitude (Raphael is cool but rude, Michelangelo is a party dude…”).

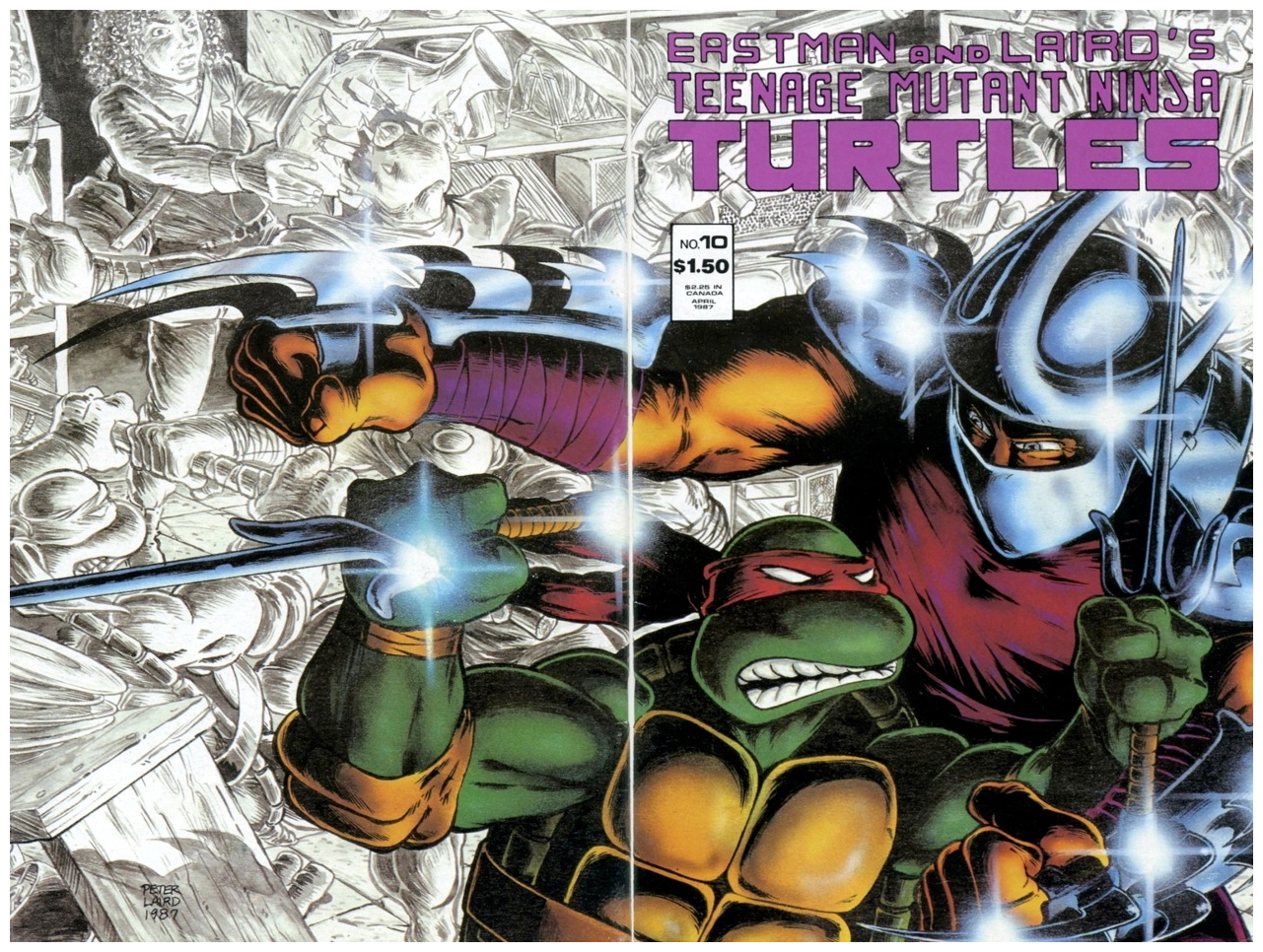

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles aren’t afraid to roll out quips and tricks while protecting their beloved New York City but, in the 2014 film, you’ll find few references to the turtles’ rough and gutsy comic book roots. Back in 1983, after an evening of creative brainstorming, Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird came up with the idea for their first issue of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and turned the comic world on its back with a book that became an overnight success. The comic was intended to be a parody of Marvel Comics‘ The New Mutants (about teenaged mutants) and Frank Miller‘s Daredevil (about ninja clans vying for supremacy of New York City’s underworld). The origin story introduces us to four turtles – Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Donatello – who have escaped from a pet store into the sewers beneath the city. When the same radioactive canister that falls off a truck and endows Matt Murdock aka Daredevil with his super-senses continues to spread its toxic radiation into the sewers, it mutates the turtles.

The four young turtles gain sentience and superpowers. They train with a rat named Splinter (a reference to Stick in Daredevil) and learn to become ninjas. Eastman and Laird tried to sell their very novel concept to both Marvel and DC Comics, but neither company was interested in a comic book about turtles. So they scraped together enough money (much of it coming from a tax refund) and published it themselves, using Mirage Studios as their imprint. The first three thousand copies sold very quickly, then the second printing of six thousand copies sold out in half the time of the first, and the third printing was even more. Within a couple of months, they had sold 50,000 copies, and parlayed their original creations into a huge licensing deal that included T-shirts, action figures, Halloween costumes, coffee mugs and much more. Almost overnight, Eastman and Laird became millionaires.

An animated series was produced in 1987 by Murakami-Wolf-Swenson Film Productions. The Saturday morning syndicated show began with a five-part miniseries that established the Ninja Turtles as four wisecracking superheroes who were obsessed with pizza and fighting criminals. The show went through several changes between 1987 and 1994, but essentially remained the same and, in 1988, Archie Comics licensed the family-friendly cartoon show and published a series of comics specifically aimed at younglings. The terrapins finally made it onto the big screen with Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1990), the first of a trilogy of live-action films. Directed by Steve Barron and scripted by Todd Langen and Bobby Herbeck, the movie returned the story to its humble origins as told in the very first issues, and dealt with the Turtles’ first confrontation with Shredder and his Foot Clan (a reference to the Hand Clan in Daredevil). The Turtles come to life in the first film thanks to two primary ingredients – outstanding costumes and puppetry provided by Jim Henson‘s Creature Shop, and martial arts choreography provided by Golden Harvest studios, responsible for the world’s best Kung Fu movies.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret Of The Ooze (1991) dealt with canister of dangerous chemicals that make them revert back to infant turtles. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles III: Turtles In Time (1993) concerns a magical sceptre the boys take back in time to feudal Japan, where they end up fighting Lord Norinaga and an Englishman named Walker – in reference to the characters played by Toshiro Mifune and Richard Chamberlain in Shogun (1980) – to prevent a war. All three films were made with children in mind and feature little content that adults would find interesting. A fourth feature film, simply titled TMNT (2007), showcased the groundbreaking computer generated imagery of Image Animation Studios. Instead of puppets and actors in rubber suits, the Turtles and their various friends and allies were digitally rendered. With a grittier look that reflects the earlier comics, this film was designed to appeal to both adults and kids, and might actually be the best of the franchise.

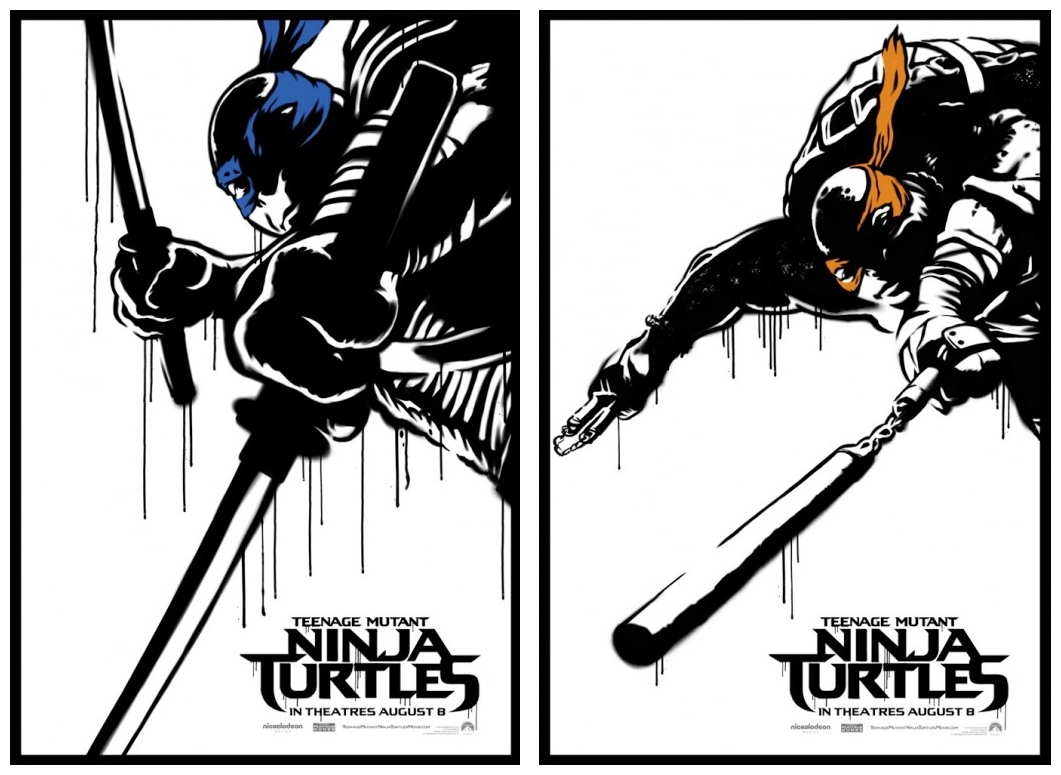

Produced a few years later, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (2014) was an attempt to the reboot the film franchise after co-creator Peter Laird sold the rights to the characters to Nickelodeon in 2009. Starring Megan Fox, Will Arnett, William Fichtner and Whoopi Goldberg (“My daughter was a huge fan of the original TMNT cartoon so when the original movie was announced she wanted me to be in it and so I asked around but it never happened, same with the other films they made, so when I heard this new project get announced I asked around again and to my surprise I got the part!”), the reboot was produced by Michael Bay, Andrew Form and Brad Fuller: “With this project we wanted to satisfy generations of fans while bringing in new fans. There is a darker, edgier element to this film that hasn’t been seen before with the Turtles, but we were equally focused on retaining the fun, which is what they’re all about.” That lifelike joke-slinging camaraderie between the four Turtles was at the forefront of the filmmakers’ minds, particularly when considering CGI. The Turtles are humanoid and, as soon as you see them, you realise that the designers have pushed them further towards homo-sapiens than we’ve ever seen before.

Co-producer Andrew Form: “We felt this movie had to be first and foremost about the characters. We knew the technology was going to be exciting and we loved the idea that we could have the Turtles doing amazing things they couldn’t imagine doing twenty years ago. But it was equally about giving audiences a fresh experience of who the Turtles are. Ultimately, our focus was to tell a real story about four close-knit brothers and the making of a family.” The producers decided that they needed a pretty green talent to come in and instil the Turtles with the gumption they envisioned, while also giving credence to the exciting night-time story-scape they had created. After talks with Brett Ratner fell through, they hired South African director Jonathan Liebesman, who had been responsible for the epic fight scenes in Battle: Los Angeles (2011) and Wrath Of The Titans (2012). “Jonathan had the experience with CG characters and, more importantly, he’s shown the ability to make action feel real. The action sequences he created for Battle: Los Angeles were so fantastic, we hoped to bring that same realistic feel to the Turtles.” Liebesman was absolutely elated to enliven the terrapins he adored so much as a kid. “I grew up with the Turtles and loved their humour but what was so exciting to me is that, with today’s technology, I knew we could give them a new scope previously unattainable. We brought in all the humour and charm while allowing the Turtles to have the kind of big action moments people love in movies today.”

He was never stumped on how to approach his re-invention, either. Liebesman insists that the Turtles’ humorous antics, mutant origins and ninja skills were the top three facets he thought were the most important, and in that order. He drew up a personality chart for each Turtle: Leonardo (voiced by Johnny Knoxville) was inspired by Tom Hanks‘ unshakable commander from Saving Private Ryan (1998); Donatello (voiced by Jeremy Howard) was inspired by Leonard Nimoy‘s common-sense Spock; Raphael (voiced by Alan Ritchson) was inspired by Clint Eastwood‘s unflappable gunfighter; and Michelangelo (voiced by Noel Fisher) was inspired by Bill Murray‘s Peter Venkman in Ghostbusters (1984). “In re-inventing the Turtles we hoped to focus on their personalities while also making them a little larger than life, a little darker in design. We were inspired to make them fun and badass at the same time.” Enough about the awesome marriage of ninja skills and badass attitude you’ll find in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, let me take the opportunity here to flesh out the story of this divisive action movie.

April O’Neil (Megan Fox was pregnant with her second son during filming) is a young hot-shot reporter who doesn’t mind spending her extracurricular hours getting the dirt on a story, and has been running around New York City at night researching the belligerent Foot Clan, who have been menacing the city. During one of their many attacks, she witnesses a group of anthropomorphic turtles who save the day and, despite no one believing her crazy story, makes friends with the crew (so far so good, you may think, but it’s at this point the writers – Josh Appelbaum, Andre Nemec, Evan Daugherty – completely change the origins of the Turtles. This particular origin tale is based on the 2011 IDW comic series, perhaps in an effort to avoid possible litigation from Marvel‘s lawyers. TMNT began life as an unofficial spin-off from Daredevil, after all). April suddenly remembers her father’s science experiment – Project Renaissance – which involved four turtles named Leonardo, Michelangelo, Donatello, Raphael and a mutated rat named Splinter (voiced by Tony Shaloub).

April’s co-worker Vernon Fenwick (Will Arnett) drives her to see Eric Sacks (William Fichtner), her father’s former partner. We discover that, before his death, April’s father and Sacks had been experimenting with an extraterrestrial mutagen developed to cure disease, which was thought lost in the fire that killed her dad. Later, the Turtles invite April to their sewer lair, where Splinter explains that it was April who had saved them all from the fire and freed them into the sewers. The mutagen caused the five of them to grow and develop humanoid attributes. After finding a book on Ninjutsu in a storm drain, Splinter proceeded to teach himself, then the Turtles, in the fighting style. Splinter also informs her that Sacks turned on her father and killed him. Shredder and the Foot Soldiers attack the lair, defeating Splinter and incapacitating Raphael while the other Turtles are captured and taken away. April comes out of hiding and she and Raphael plan to save the others. Raphael, April and Vern break into Sacks’ mansion, free the other Turtles, and escape the compound in pursuit of Sacks, who intends to plant a device that will flood the entire city with a deadly virus.

The critics were brutal. Chris Cabin: “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles only leaves one with the dim afterglow of forced normalcy, of a film so overworked to ensure mass-market appeal that it loses the charming oddness and loose goofiness that has allowed these characters, and their ‘frothy’ appeal, to endure.” A.A. Dowd: “What the new Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles lacks is not fidelity, but a spirit of genuine boyish fun – the sense that anyone involved saw more than a very specific shade of green in the freshly digital scales of these thirty-year-old characters.” Steven Rea: “The kind of cliched, misfit-crime-fighters-versus-demented-villains scenario that Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird happily parodied when they came up with the original Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comic books way back in the 1980s.” Cliff Lee: “For having gone to the trouble of making a self-descriptive movie called Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, its producers seem ultimately unsure about its most basic concept.”

Justin Lowe: “Liebesman relies on his genre-film resume to keep events moving at a brisk clip and the motion-capture process employed to facilitate live-action integration with cutting-edge VFX looks superior onscreen.” Rotten Tomatoes: “Neither entertaining enough to recommend nor remarkably awful, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles may bear the distinction of being the dullest movie ever made about talking bipedal reptiles.” Mark Olsen: “There is something half-hearted about the entire film, as if those behind it were involved not because they wanted to make it, not because they should make it, but just because they could.” Bill Goodykoontz: “It’s just kind of a mess, as unfocused and immature as the four mutant turtles at its core. Stuff happens, stuff blows up and this is probably a good time to mention that Michael Bay produced the film.” Alonso Duralde: “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles is a movie that takes its characters and its premise seriously, until it doesn’t, and that operates at two speeds: tortoise (ponderous) and hare (head-spinning).”

James Berardinelli: “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles doesn’t so much provide brainless enjoyment as it pummels the viewer into submission. ‘Shell-shocked’ is a reasonable description of the experience.” With a budget of US$125 million, the film was declared a financial success, taking almost US$500 million at the box-office, and a sequel was immediately green-lighted entitled Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out Of The Shadows (2016) which turned out to be equally as mediocre. Mildly entertaining while on the screen but ultimately forgettable, both of these films suffer the same problem as every other adaptation of the popular comics. The filmmakers always seem to forget that the Turtles were created as a parody of superhero comics, in both style and content, in particular Frank Miller‘s version of Daredevil – in fact, in the film of Daredevil (2003), actor Jon Favreau has a running gag concerning ‘giant alligators in the sewers’ which, in the original script, was written as ‘giant turtles in the sewers’. Oh well, better luck next week, when I discuss another roadkill on the motorway of mediocrity for…Horror News! Toodles!

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (2014)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews