SYNOPSIS:

“Flash Gordon is an American football player who, along with Dale Arden, is returning to New York City after a long vacation, until the plane they are passengers on crashes into the laboratory of Russian scientist Dr. Hans Zarkov. Both Flash and Dale become unwilling passengers on-board Zarkov’s rocketship as Zarkov sets a course for the planet Mongo. Arriving on Mongo, Flash and his companions find the planet is under the rulership of the evil Emperor Ming the Merciless and Ming is attacking Earth with natural disasters as he bids to destroy Earth. Realising that Earth and the human race is in mortal danger, Flash decides to unite the kingdoms of Mongo and combine the forces of rivals Prince Barin and Prince Vultan to rescue Dale, who is to become Ming’s wife and defeat Ming and save Earth from annihilation.” (courtesy IMDB)

REVIEW:

Writer Don Moore and artist Alex Raymond created a superhero named Flash Gordon for a daily King Features comic strip in order to compete with the huge audience that was reading Buck Rogers In The 25th Century in rival newspapers. The strip debuted with a full page in January 1934 and packed a punch with each of its comic panels. In no time at all, Flash Gordon surpassed the popularity of Buck Rogers and gave America a new hero who had no superpowers, but had all the grit and determination of a modern American. Famous polo player Flash Gordon is forced to parachute from a passenger plane when it is struck by a falling meteor. Both Flash and beautiful Dale Arden, whom he managed to grasp in his arms on his way out the plane door, land near a launch site where Doctor Hans Zarkov plans to rocket into space for the rogue planet known as Mongo. Zarkov can’t stop the countdown, nor does he have time to argue with his two new guests. With mere seconds before the rockets on his spaceship turn the launch site into a fiery inferno, he takes Flash and Dale aboard his ship.

They rocket to the planet Mongo, which is on a collision course with Earth, and try to plead with Mongo’s evil emperor Ming the Merciless to turn away from his destructive course. Ming takes an immediate liking to Dale, sends Zarkov to work with other enslaved scientists, and sentences Flash to death. For the next ten years, Ming tried every means at his disposal to get rid of Flash, while our heroes became involved with Mongo’s improbable inhabitants in a string of memorable adventures. Those adventures included encounters with Prince Vultan of the Hawkmen, King Kala of the Shark Men, Prince Barin of Arboria, and Ming’s own daughter Princess Aura. In 1935, the strip was adapted as a twenty-six-episode radio show exhaustingly entitled The Amazing Interplanetary Adventures Of Flash Gordon. The following year Universal Pictures produced a thirteen part movie serial with Buster Crabbe in the titular role, and did so again in two further serials: Flash Gordon’s Trip To Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers The Universe (1940).

The daily comic strip went into hiatus in 1944 when Alex Raymond joined the army, and returned in 1951. When television began adapting popular serials for the small screen, Flash Gordon was among its first shows, starring Steve Holland in thirty-nine episodes broadcast in 1954-1955, filmed in West Berlin less than a decade after World War Two. Jumping to the seventies, a pornographic parody entitled Flesh Gordon (1974) was released and became a cult favourite among science fiction fans, primarily because of the frankly amazing special effects by artists such as David Allen, Rick Baker, George Barr, Doug Beswick, Jim Danforth, Greg Jein, Mike Minor, Dennis Muren and Bjo Trimble, many of whom would be hired to work on Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977). When George Lucas first envisioned Star Wars, he wanted to make a space opera not unlike the old Flash Gordon movie serials. In fact, he first pitched Universal Studios on a remake of Flash Gordon but the rights had already gone to Dino De Laurentiis who, prompted by the success of Star Wars, decided to launch his own space opera.

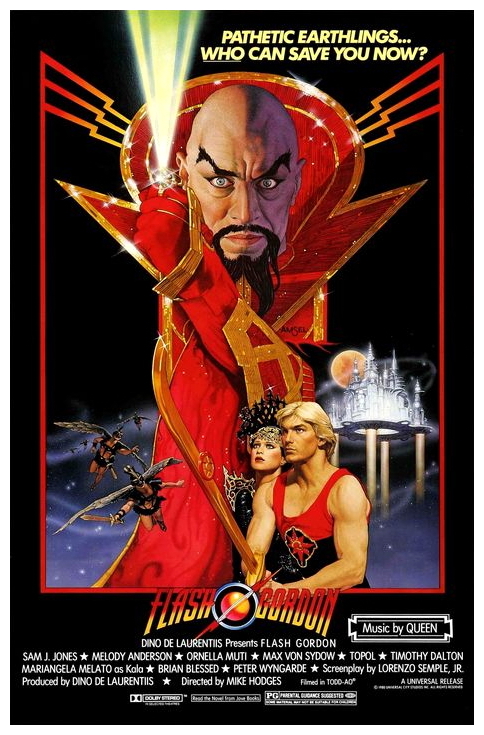

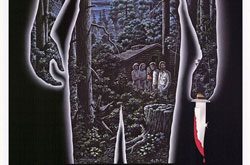

When Flash Gordon (1980) first came out, many twelve-year-olds (at whom it was aimed) didn’t know what to make of it. In the wake of other science fiction blockbusters such as the Star Wars films and television shows like Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers In The 25th Century, they expected a big budget space opera. Twelve-year-olds are not necessarily the best audience for retro-camp. Football star Flash Gordon (Sam J. Jones) is caught up with reporter Dale Arden (Melody Anderson) and former NASA scientist Doctor Hans Zarkov (Chaim Topol) in fighting the intergalactic villain Ming (Max von Sydow), who is in the process of destroying Earth. While on Ming’s planet Mongo, the trio find themselves at odds, and eventually allies, with various other alien races trying to survive under Ming’s merciless rule (all the kingdoms and continents on Mongo are now moons or floating islands, a rogue mini-system in constant chaos). Initially, producer De Laurentiis wanted Federico Fellini to direct the picture, and Fellini optioned the rights, but his involvement was minimal.

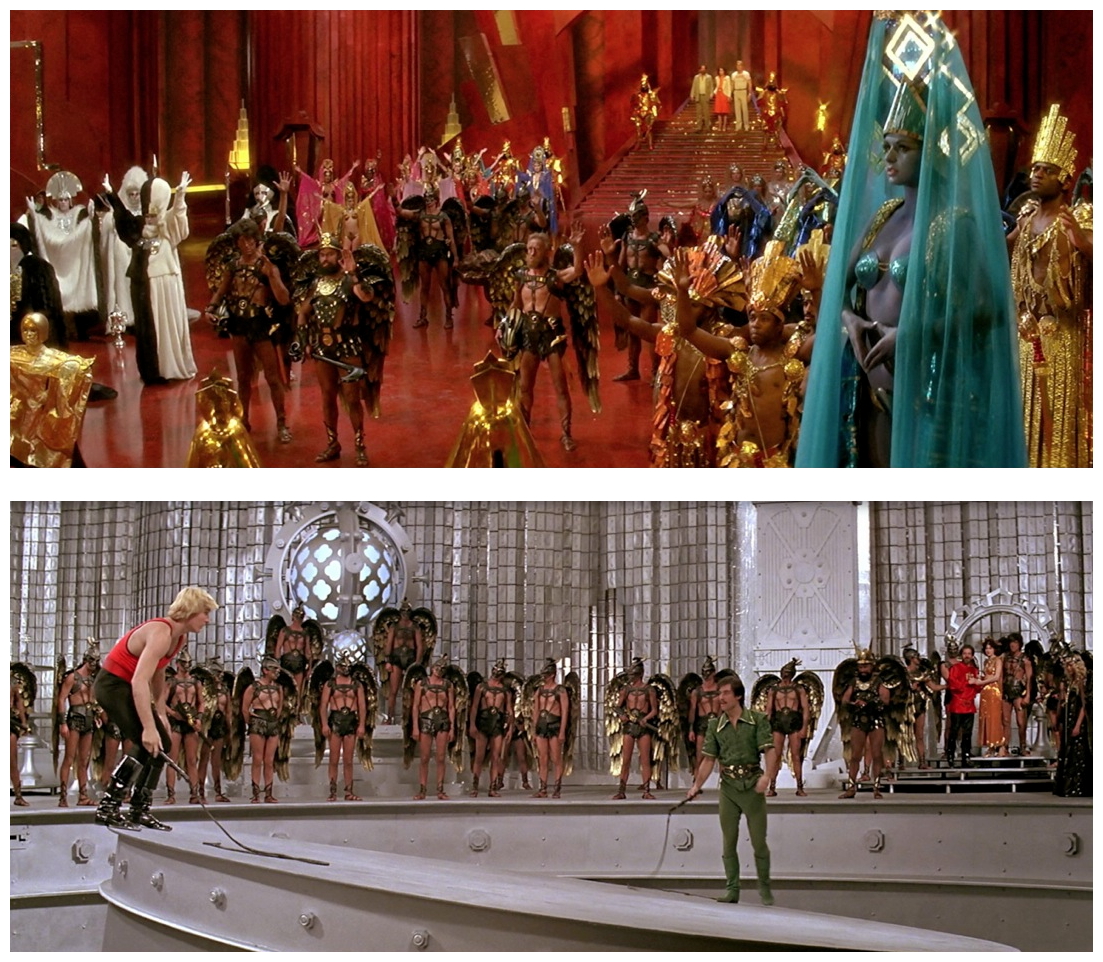

De Laurentiis then hired Nicolas Roeg, an admirer of the original comics, who spent an entire year on pre-production, but was eventually fired because De Laurentiis didn’t appreciate his sado-masochistic take on the material. De Laurentiis then asked Sergio Leone to direct, but he refused due to the less-than-serious script. Number eight on Dino’s wish list was British director Mike Hodges, whose very down-to-earth catalogue includes Get Carter (1971), Pulp (1972) and The Terminal Man (1974). Hodges wanted to create a film aesthetic that directly reflected its origin, much like Robert Altman tried to do in Popeye (1980). The opening credits use illustrations from the early comic strips, along with Queen’s now famous theme song and, throughout the movie, Hodges chooses film angles, framings and colours to evoke the comics. “I turned it down because I thought it wasn’t my kind of film, because it was totally different from what I had previously done. Our Flash Gordon is not really science fiction. It’s a comic strip in another galaxy, not in the region of Star Wars.”

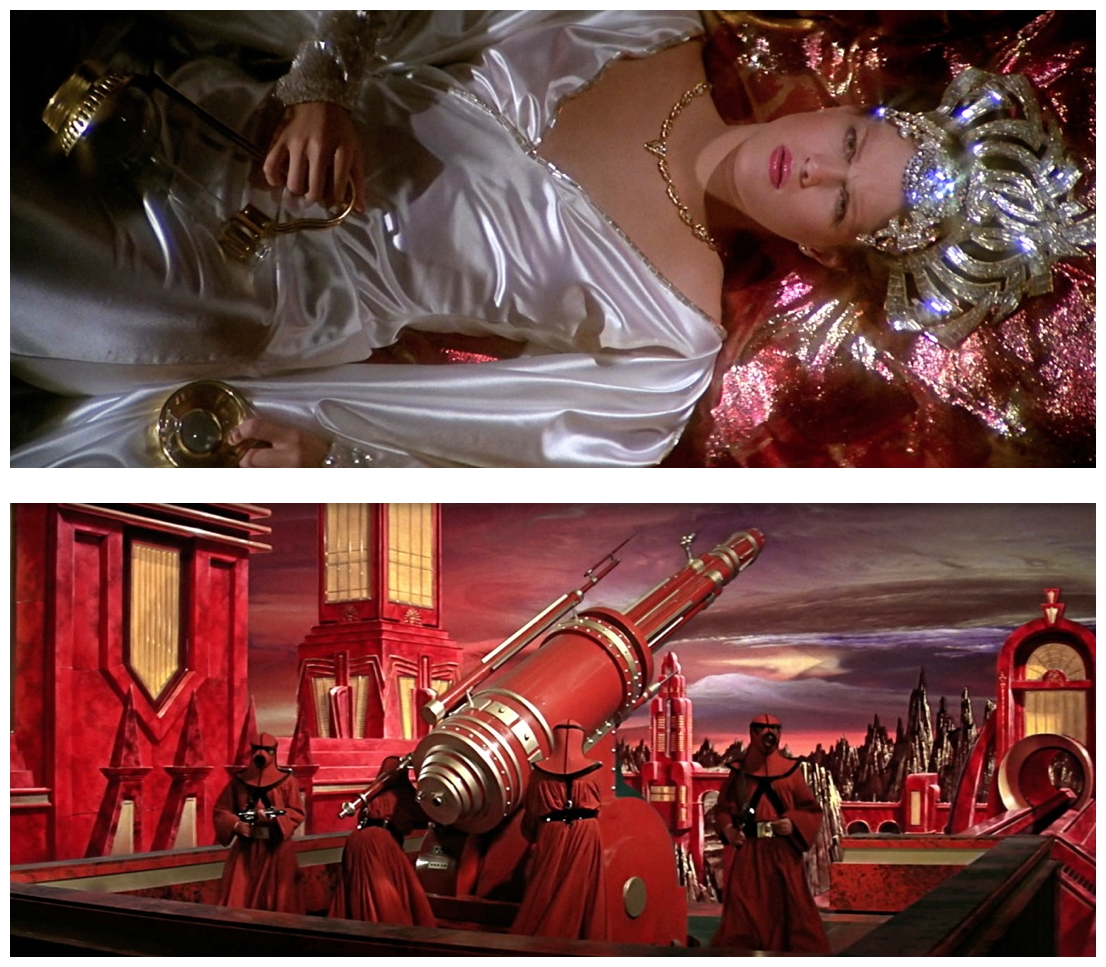

“It looks almost exactly like Alex Raymond‘s cartoon story. This film is much bigger than the Buster Crabbe features. They were fun to watch but they had primitive special effects. This film has fantastic special effects, is shown on the wide screen and in colour. I didn’t even know about Flash Gordon until I was well into my teens. I did read Asimov and people like that, but I was never really drawn to it. I certainly did enjoy Star Wars. The Empire Strikes Back (1980) was not quite as enjoyable. Parts of Superman (1978) were very good, and there were some interesting aspects to Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977). We had to be sure not to copy them. For example, we had to design laser beams that had different ways of disposing of villains. We wanted them to be more like the cartoons, with different skies and colours. We wanted each of Ming’s outposts surrounded by a different atmosphere, it was really daunting to begin. Finally we got Oxford Scientific, which has done effects for a number of nature films, including David Attenborough‘s Life On Earth, to do some micro-photographic effects.”

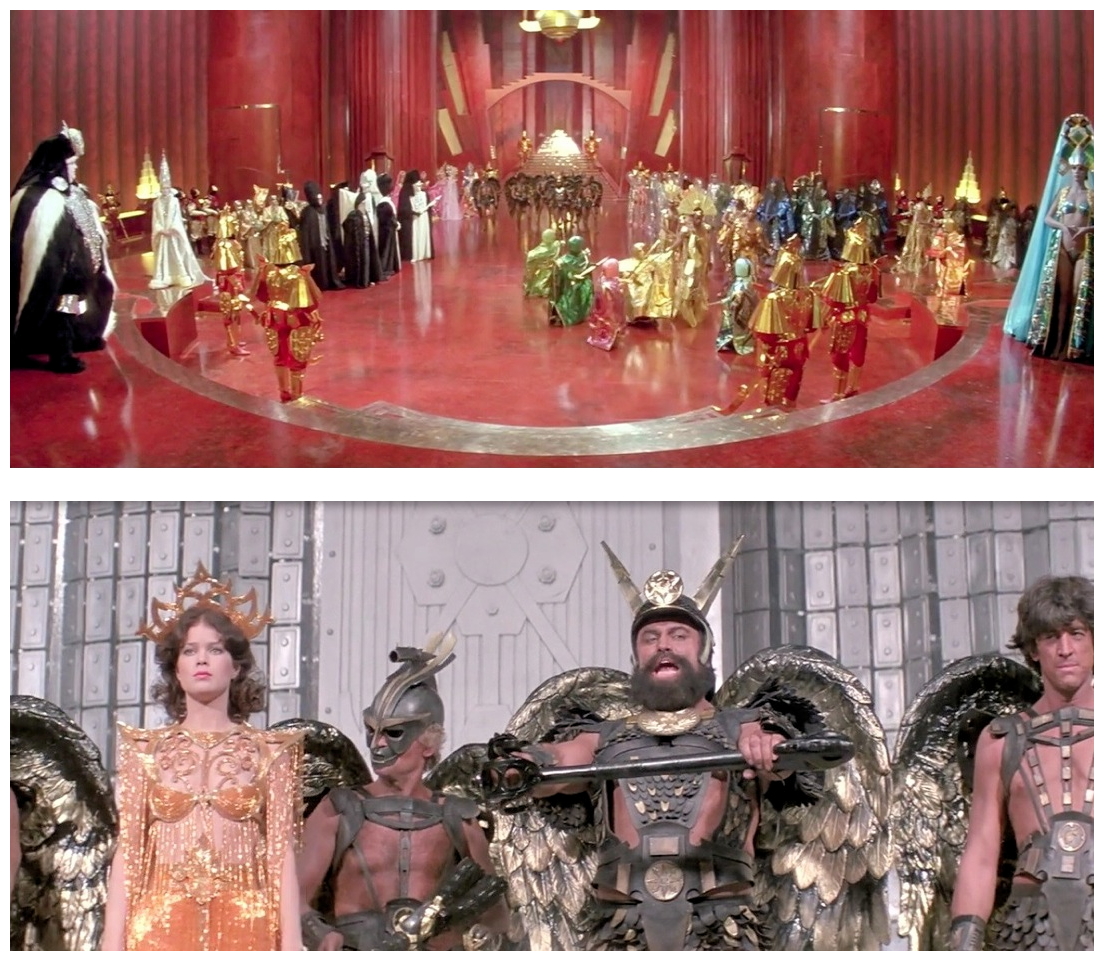

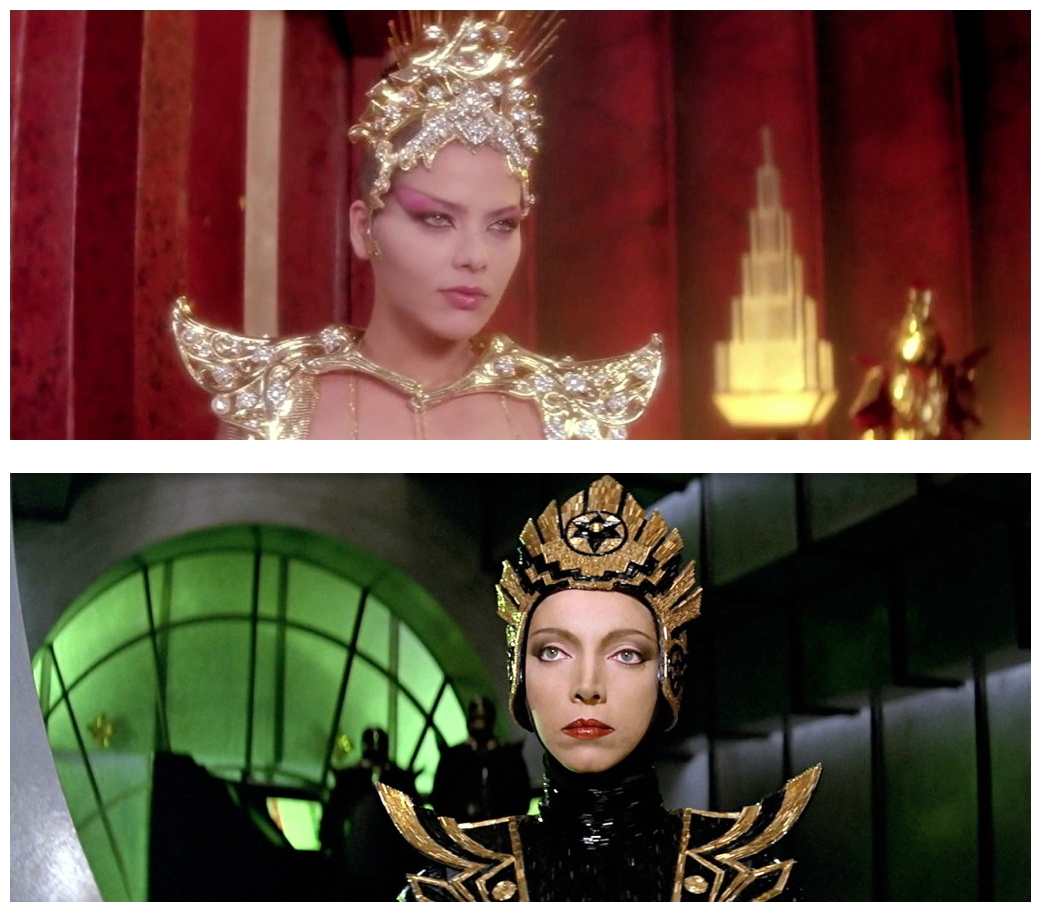

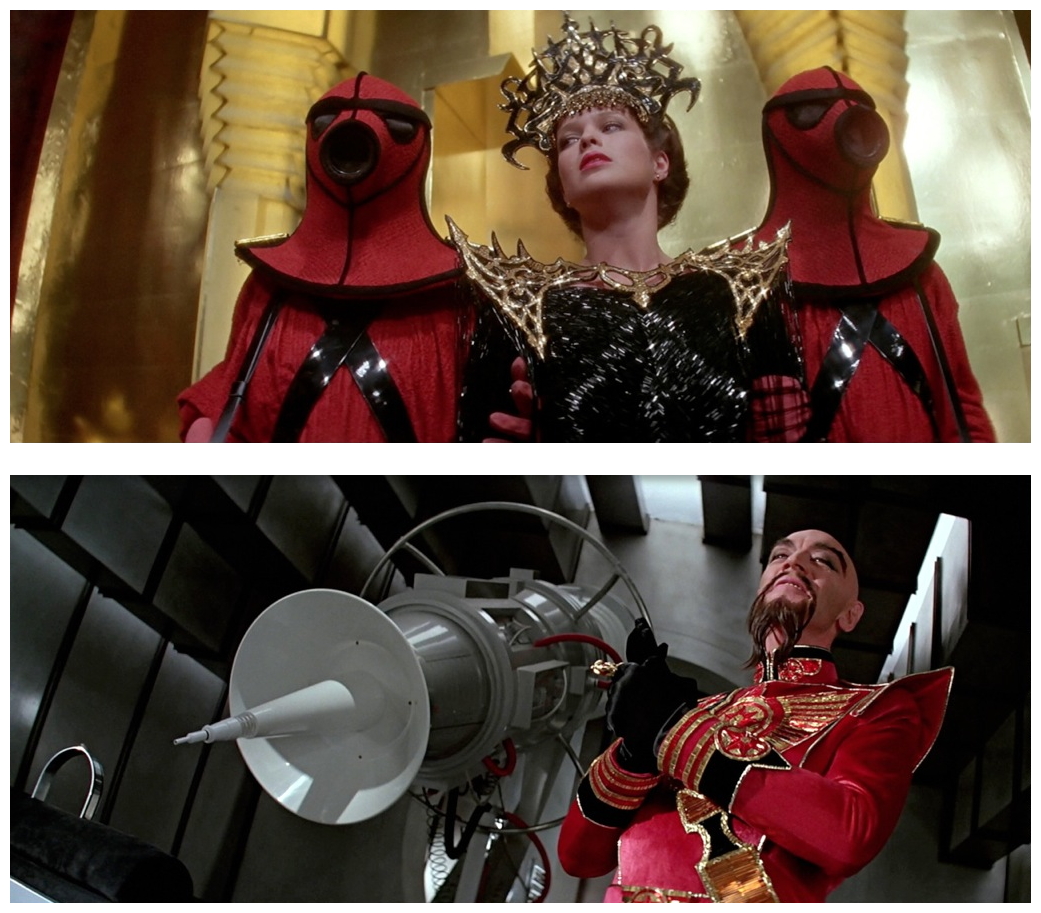

“They were unable to carry on for us, but we were able then to create our own skies from our own tanks of water. Actually, in retrospect, it was hysterically funny because we had these guys on wires who were gamely upside-down ’til we got some pattern. It was really difficult to make them look realistic and to coordinate everyone. Finally we had to hire ballet dancers because they could move gracefully on wires. The problem was, they also had to be big. Max von Sydow, who plays Emperor Ming the Merciless, was always a hero of mine. He has a great sense of humour and is a great actor, and the woman villain Kala, played by the beautiful Italian actress Mariangela Melato looked fantastic in all that leather. The other female villain, Princess Aura played by Ornella Muti, was also very interesting.” First to be considered for the lead was Arnold Schwarzenegger, but he was rejected because of his impenetrable Austrian accent. Kurt Russell auditioned and was actually offered the role, but turned it down after reading the script, because the character was one-dimensional and lacked personality.

Finally, the inexperienced Sam J. Jones was cast after being spotted by Dino’s mother-in-law on an episode of The Dating Game. He won the very first Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Performance By An Actor In A Motion Picture but, in his defence, the blandness of the heroic lead was deliberately designed to reflect the story’s comic-strip origins. Jones’ dark hair was bleached blonde and was given blue contact lenses which he refused to wear because he found them too painful. Unfortunately, Jones kept getting into fights during the shoot and then, around Christmas, he left for Los Angeles and never returned. Jones had a falling out with De Laurentiis over lack of payment and refused to go into the recording studio to loop his own lines, so the producer panicked and ordered Hodges to finish the film using the very best stand-in he could find, which is why most of his dialogue has been dubbed. Having Ming played by respected actor Max von Sydow, best known for his collaborations with Ingmar Bergman, was a genius move in casting against type.

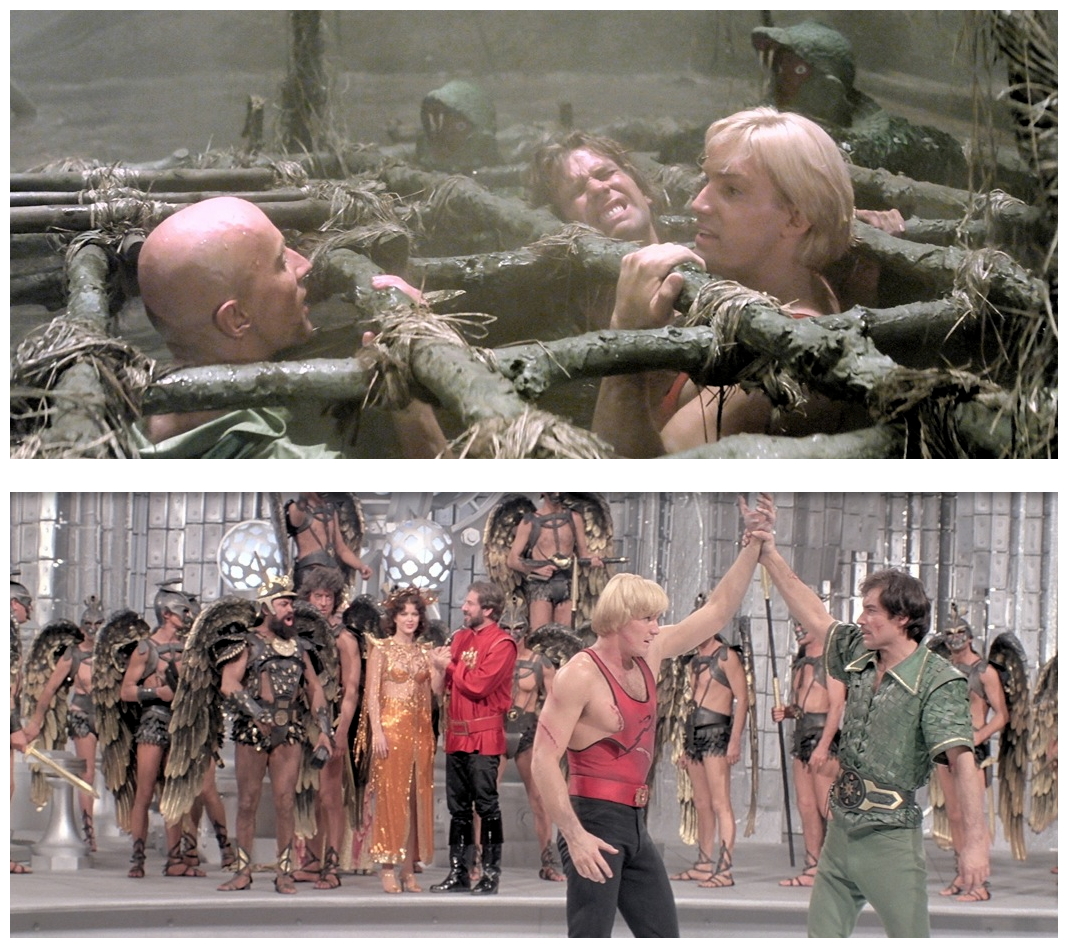

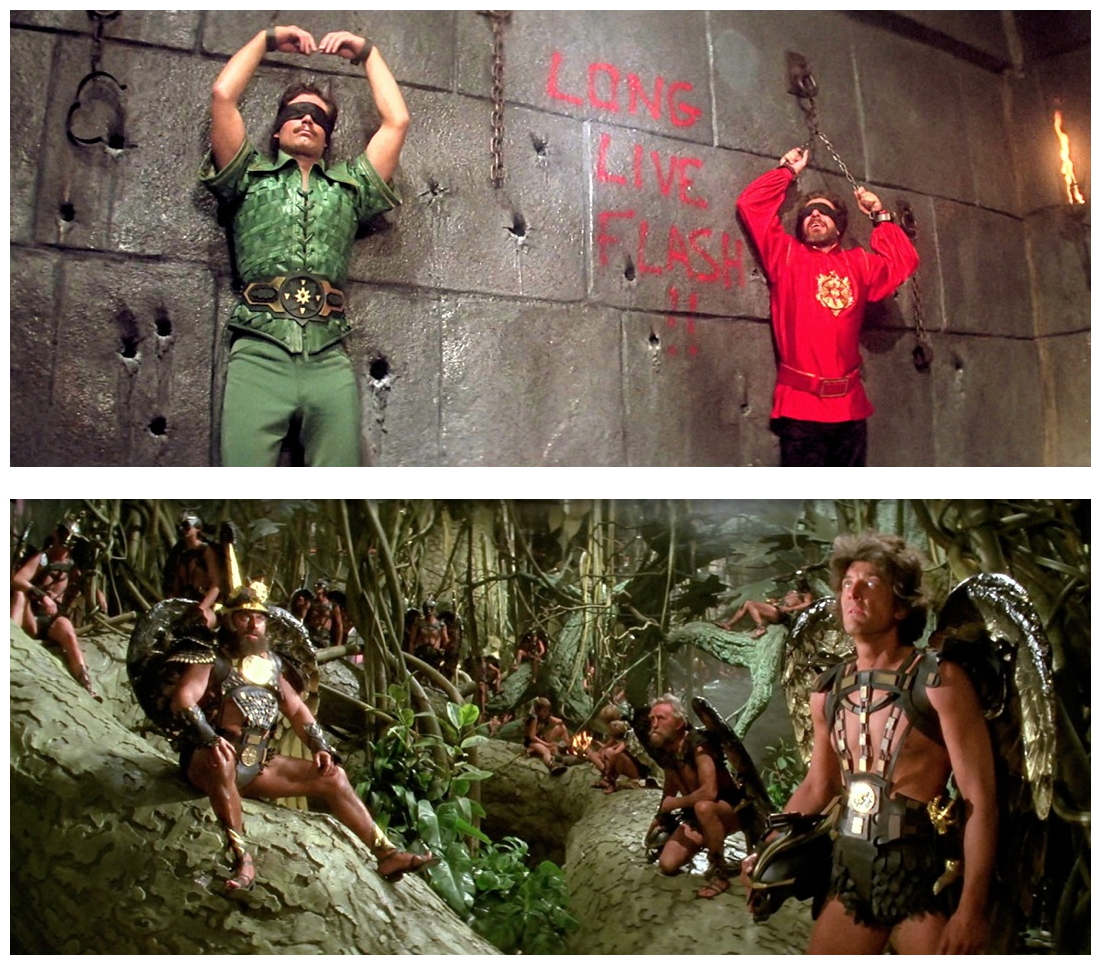

Turning the film’s campiness up to eleven, Hodges casts veteran stage actors like Jim Carter, Robbie Coltrane, Timothy Dalton, John Hollis, John Osborne, Philip Stone, Peter Wyngarde, and a huge party of dwarves including Deep Roy and two-thirds of the Time Bandits (1981): Kenny Baker, Malcolm Dixon, Tiny Ross, and Mike Edmonds. As Prince Vultan, the bombastic Brian Blessed has a whale of a time, an avid fan of the comics since childhood. He improvised the scene where Vultan pinches Dale’s bottom – Melody Anderson‘s reaction is quite genuine. In a dream sequence, Dale turns into a giant spider, so Anderson spent six hours in the makeup chair, painted green, wearing fake eyes and fangs with a head piece weighing almost ten kilos. Director Hodges walked onto the set and said, “This is wonderful, but we can’t use this, it has absolutely nothing to do with the script.” Anderson went on to appear in a few dozen television shows before retiring from acting in 1995 to become a social worker, and is now a respected international lecturer on addiction, substance abuse and other mental-health problems.

New Zealander Richard O’Brien, who plays Prince Barin’s sidekick Fico, is most famous for creating The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), and even mentions Flash Gordon in the opening song. O’Brien found the whole experience of making the film rather tedious, but got a lot of pleasure from sitting in the personalised chairs of the principal actors. His impish behaviour wasn’t curbed because he knew director Hodges very well, much to the consternation of the stars who regularly bitched about him on set. William Hootkins, who plays Zarkov’s lab assistant, was one of a handful of American actors working in Britain, along with Ed Bishop, Matt Frewer, Mac MacDonald, John Ratzenberger and Shane Rimmer. Hootkins is probably most famous for appearing in Star Wars IV: A New Hope (1977) and Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981). Down among the Tree Men is Australian Peter Duncan, who wisely gave up acting in favour of writing and producing award-winning films and television, like Children Of The Revolution (1996), Rake (2010) and Unfinished Sky (2007).

Probably the most famous aspect of Flash Gordon is its soundtrack composed and performed by the rock band Queen and lead singer Freddie Mercury. De Laurentiis had never heard of the band – their manager arranged to meet De Laurentiis to discuss the opportunity to compose the soundtrack, and he asked, “Who are the Queens?” Despite this, they were immediately interested in the prospect of working on a film, creating not only an exciting soundtrack, but also one of their most popular albums and songs, topping the charts worldwide. It was because of this De Laurentiis demanded to have a popular rock band compose and perform songs for the soundtrack of Dune (1984), hence the involvement of Toto. Flash Gordon was the first movie that Queen made the music for – in it Prince Vultan asks “Who wants to live forever?” The only other movie Queen composed the soundtrack for was Highlander (1986) which features the song Who Wants To Live Forever? Coincidence? Probably. One other nugget of trivia: Prince Thun, who is ordered to fall on his sword, has been dubbed in the film, but the actor’s actual voice (George Harris has a West Indies accent) can be heard on the soundtrack.

The album sales were not reflected in ticket sales, but it nevertheless made its money back. Flash Gordon cost US$20 million to produce and took about US$45 million internationally, but any chance of a sequel was lost when Jones walked off the movie. There were other problems. The cleverness of the casting and its kitsch-ness was lost on adolescent audiences, as were Hodges’ allusions to American foreign policy, particularly the 1979 capturing of the American embassy in Tehran during the Iranian revolution. Flash, Dale and Zarkov’s stumbling into the complexities of the politics of Mongo, particularly under a despotic dictator like Ming, has echoes in post-war American foreign policy. Then there’s the script by Lorenzo Semple Jr. No one on earth writes quite like Semple, responsible for the camp sixties Batman television series, and the tongue-in-cheek Doc Savage (1975) film produced by George Pal. De Laurentiis, who produced the comic-based films Danger: Diabolik (1968) and Barbarella (1968), loved Semple’s work (despite having little grasp of the English language) and hired him to write the screenplay for King Kong (1976).

Sadly, Semple’s sense of humour is not to everyone’s taste, and Flash Gordon goes wrong in the same way as King Kong, only more so, but it’s not entirely his fault. Semple insists he was pressured into making the film funny even though he thought it was a terrible mistake: “Dino wanted to make Flash Gordon humorous. At the time, I thought that was a possible way to go but, in hindsight, I realise it was a terrible mistake. We kept fiddling around with the script, trying to decide whether to be funny or realistic. That was a catastrophic thing to do, with so much money involved. I never thought the character of Flash in the script was particularly good, but there was no pressure to make it any better. Dino had a vision of a comic-strip character treated in a comic style. That was silly, because Flash Gordon was never intended to be funny. The entire film got way out of control.” Another problem was the rushed effects work, which shows all too clearly. Special effects supervisor Frank Van der Veer had less than nine months to put together 600 blue-screen composites of live-action and matte paintings. The flying Hawkmen look like, and are, people with cardboard wings on wires.

“In my estimation Flash Gordon has more photographic effects work in it than any other movie ever made. I’d say 75% of the movie features some sort of effect. Until recently, all movies seemed to start with a fade-in and end with a fade-out. No effects in between, just so-called ‘Realism’. I refer to it as the ‘Life Can Be Miserable’ period. By way of illustration, consider Superman (1978). On that film it was very important to convince the audience that a man could fly. I think the people on that film did a marvellous job. What complicates ours is the fact we don’t have just one man flying in a scene – we have one thousand Hawkmen. Also, they are flying in a very unusual setting. Whereas in Superman, the man of steel was flying against a fairly realistic backdrop like New York City, our Hawkmen are flying against a setting of the Mongo Galaxy, sheer fantasy. Every environment these characters enter differs from the one preceding it. Nothing can be conventional. The skies have to be different, the land is unique, the clothing is like nothing you have ever seen, and the architecture literally out of this world.”

“Our job is to pull all this off realistically, so the whole film doesn’t look like one gigantic effect. We decided we were able to fly and control seven or eight men at a time, In order to make the Hawkmen shots look like hundreds of them in the air, we would have to combine several shots in the optical printer. We put together shots which combined as many as twenty different blue-screened elements to make a single shot. But to photograph seven or eight Hawkmen at a time, it was necessary to build an enormous blue-screen. In the course of the production we used many different types and sizes, the screen we built for the Hawkmen was sixty feet high and 100 feet wide. Unfortunately, there are very few arc lights in London. Of course, it’s practically impossible to light a screen that large with arcs anyway. Can you imagine how many arcs would be required? And can you imagine how many men you’d have managing those arcs? And can you imagine the scaffolding you’d have to support those arcs?”

“And then somebody would always be trimming an arc! Not only that but, in trimming the arc, when they swing the lamp around to put a new arc in, they put it back the way they think they had it before, right? When you have a hundred guys doing that, they don’t get back to the same place! Then you’d have a tremendous smoke problem too. We finally had to do it with incandescent lights. We built special lights which were clusters of quartz-halogen lights – we called them ‘Dinos’. They put out a tremendous amount of heat, but they also put out a tremendous amount of light. Just to light that one background screen took a million watts of power. So you haul up the Hawkmen in front of the blue-screen for a take. All of a sudden you notice the second guy from the left, his right wing isn’t working right, so you fix that and set up again. Then oops, the third guy from the right forgot his gun. Okay, once more. Then you notice that the people pulling the wing wires making them flap are not together. Some are too fast, some are too slow. Well, after four minutes in the air, the guys are getting tired, they can’t hold their bodies in that awkward position for more than four minutes.”

“Then, too, the constant friction of the wings on the wires kept rubbing the blue paint off, so the wires are constantly having to be repainted and you have to make sure to light the wires as carefully as possible so they don’t show up. Finally, after everything is flying and moving properly you have to worry about the camera – you have to move the camera or zoom the lens or whatever to get the illusion of movement. Sometimes the Hawkmen are hovering, sometimes they are zooming, sometimes they are going away from you and sometimes they are coming towards you and, of course, those movements require different types of rigging which, of course, takes time to set up. We had some 600 blue-screen shots to do for this picture. The reason there were so many was because of the alien sky effects. On Mongo all of the skies are very unique, so if there is a window in the set or a doorway or anything that lets you see the outside, it meant that blue-screen photography was necessary to insert one of these unique sky effects.”

“The absolutely gorgeous clouds and skies took months and months of work to produce. The sky and cloud effects took a tremendous amount of expertise and experimentation, the results are unbelievable. They have stratas that go in different directions, they have different types and colours of clouds. Arboria is greenish, of course, Ming’s city is reds and yellows, Sky City was purples, cyans and blues.” Sam J. Jones (an unknown and therefore presumably inexpensive actor) plays Flash with all the emotional expressiveness of a cigar-store wooden Indian. As for the story – old-style space opera of the zaniest kind, reasonably faithful to the original Flash Gordon serials – it’s all done so charmlessly that it holds little interest. Only the set designers and costumers show any flair – the film is a paradise for leather gear fetishists, and looks like a convention of the kinkiest designers in Europe. It’s a real pity that the film was not directed, as originally planned, by Nicolas Roeg.

Despite (or perhaps because of) these problems, Flash Gordon has since become a cult classic. It is a favourite of director Edgar Wright, who used the film as one of the visual influences for Scott Pilgrim Versus The World (2010). Comic artist extraordinaire Alex Ross insists it’s his favourite film of all time, and painted the cover of the Saviour Of The Universe edition of the DVD. In Seth MacFarlane‘s comedy Ted (2012), the main characters are fans, and Jones himself appears during a manic party sequence. Blessed’s performance as Vultan became locked into the British collective consciousness for the utterance of a single line (“Gordon’s alive?!”) which, almost four decades later, remains the most repeated quotation from both the film and Blessed’s lengthy career. Right now I’d like to thank Starlog #45 for assisting my research for this article, and ask you to join me again next week so I can poke you in the mind’s eye with another pointed stick from the faggot formerly known as Hollywoodland for…Horror News! Toodles!

Flash Gordon (1980)

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

Nigel Honeybone takes on my favorite childhood film: I don’t think you like it quite as much as I do. For me, as a youth it was amazing spectacle and fun. Now as an adult I feel the comedy works brilliantly (Ming has numerous witty quotable lines). I found this film (and still do) infinitely more fun than Star Wars. It’s a unique movie Hollywood would never make now… especially since big budget films are made by committee.

Great review chock full of interesting and amusing trivia. I very much enjoyed reading it.

P.S. I dare you to take on Disney’s oddest movie, ‘The Black Hole’, with the same insightful approach.

Thanks for reading! I guess I have a love-hate sort of relationship with Flash. I actually enjoy Lorenzo Semple Jr’s writing – as I say, no-one writes dialogue quite like him. Unfortunately, this requires his heroes to be little more than stiff cardboard cutouts. The late great Adam West (who sadly passed away today) in Batman, Ron Ely in Doc Savage, and Sam J. Jones are all cut from the same cardboard. Agreed, it wouldn’t be made today – imagine, with inflation, you’d need at least $150 million to pull off a film at the same scale today. I said a more serious version of Flash is required but, reconsidering, it might make a good vehicle for Gore Verbinski after the Pirates Of The Caribbean films, with Johnny Depp as Ming… yes, it’s just so crazy it might just work! Get Michael Bay on the phone…